Mutations in MYBPC3 are the cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Although most lead to a truncating protein, the severity of the phenotype differs. We describe the clinical phenotype of a novel MYBPC3 mutation, p.Pro108Alafs*9, present in 13 families from southern Spain and compare it with the most prevalent MYBPC3 mutation in this region (c.2308+1 G>A).

MethodsWe studied 107 relatives of 13 index cases diagnosed as HCM carriers of the p.Pro108Alafs*9 mutation. Pedigree analysis, clinical evaluation, and genotyping were performed.

ResultsA total of 54 carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9 were identified, of whom 39 had HCM. There were 5 cases of sudden death in the 13 families. Disease penetrance was greater as age increased and HCM patients were more frequently male and developed disease earlier than female patients. The phenotype was similar in p.Pro108Alafs*9 and in c.2308+1 G>A, but differences were found in several risk factors and in survival. There was a trend toward a higher left ventricular mass in p.Pro108Alafs*9 vs c.2308+1G>A. Cardiac magnetic resonance revealed a similar extent and pattern of fibrosis.

ConclusionsThe p.Pro108Alafs*9 mutation is associated with HCM, high penetrance, and disease onset in middle age.

Keywords

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) represents the most common inherited cardiac disease, affecting 1 in every 500 people in the general population.1,2 Classically, it is defined by the presence of a hypertrophied, nondilated left ventricle (LV) in the absence of any cause capable of producing the magnitude of hypertrophy, such as pressure overload or storage/infiltrative diseases.3,4 Genetic mutations can be identified in approximately 60% of patients and are most common in genes encoding proteins of the cardiac sarcomere. These mutations are characterized by incomplete penetrance and variable clinical expression.5 The most frequently involved gene is MYBPC3, which encodes myosin-binding protein C.6,7 More than 150 HCM-causing mutations in MYBPC3 have been reported to date. In contrast to other disease genes, in which most the mutations are missense, approximately 70% of MYBPC3 mutations result in a frameshift creating a premature termination codon leading to a C-terminal truncated protein.6,8 Information on genotype-phenotype correlation is still weak, and distinct mutations (including mutations with the same effect on the protein) in the same gene seem to behave differently in terms of clinical presentation and outcomes.9–11 Nevertheless, the evidence is based on a reduced number of studies and reports in small groups of patients. The present study sought mainly to establish the pathogenicity of these mutations and to describe the clinical phenotype of a novel MYBPC3 mutation (p.Pro108Alafs*9) present in 13 different families from southern Spain. The secondary aim was to compare the phenotype of the 2 most prevalent mutations of the MYBPC3 gene reported in Spain (p.Pro108Alafs*9 and c.2308+1 G>A (IVS23+1 G>A).

METHODSAn expanded “Methods” section is available in the .

Study PopulationThirteen apparently unrelated index cases with HCM (aged 40.7±14.6 years, 9 men [75%]) who were carriers of the same novel mutation p.Pro108Alafs*9 in the MYBPC3 gene (GenBank accession number 4607) were enrolled in the study. All patients underwent risk stratification and were managed following recommended guidelines.12 A pedigree was drawn for each patient, and first-degree relatives were screened using the same protocol. The phenotypes of p.Pro108Alafs*9 and c.2308+1 G>A were compared.

See the expanded “Methods” section in the for a detail description of genetic study, RNA isolation, complementary DNA synthesis, MYBPC3 complementary DNA amplifications, puromycin analysis and statistical analysis.

RESULTSWe identified a novel mutation in the MYBPC3 gene (p.Pro108Alafs*9). A founder effect was confirmed. A total of 107 individuals (mean age 42.0±20.1 years; 52 [48.6%] men) from the 13 families with the p.Pro108Alafs*9 mutation were evaluated. In the clinical study; 39 individuals (36.4%) met the diagnostic criteria for HCM (Table 1), 7 (6.5%) were classified as possible HCM, and 45 (42.1%) were considered as clinically unaffected.13 We excluded 16 relatives with unrelated cardiac abnormalities.

Characteristics of the 39 Clinically Affected Carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9

| Female | Male | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 13 (33.3) | 26 (66.7) | .005 |

| Age, y | 65.5±17.4 | 50.5±15.9 | .011 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 52.7±15.5 | 38.4±15.9 | .011 |

| Reason for diagnosis | |||

| Incidental | 1 (7.7) | 7 (26.9) | .161 |

| Family screening | 6 (46.2) | 11 (42.3) | .819 |

| Symptoms | 6 (46.2) | 8 (30.8) | .345 |

| Hypertensive | 6 (46.2) | 9 (34.6) | .773 |

| Abnormal ECG | 11 (84.6) | 18 (69.2) | .300 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (46.2) | 10 (38.5) | .645 |

| Maximal LVH, mm | 19.2±4.7 | 20.5±7.5 | .570 |

| Severe LVH, mm | 0 (0.0) | 4 (15.4) | .135 |

| LVNC | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | .474 |

| Obstruction | 4 (30.8) | 6 (23.1) | .604 |

| Severe obstruction | 2 (15.4) | 4 (15.4) | 1 |

| Pattern | |||

| No hypertrophy | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | .126 |

| ASH | 5 (38.5) | 11 (42.3) | .946 |

| Concentric | 2 (15.4) | 4 (15.4) | .877 |

| Others | 5 (38.5) | 11 (42.3) | .818 |

| Left atrium, mm | 43.5±9.5 | 45.5±7.7 | .493 |

| LVEDd, mm | 45.5±4.3 | 44.9±7.8 | .796 |

| Systolic impairment | 4 (33.3) | 10 (43.5) | .561 |

| Mitral regurgitation III-IV | 2 (15.4) | 3 (11.5) | .735 |

| NYHA III-IV | 7 (53.8) | 6 (23.1) | .055 |

| Syncope | 3 (23.1) | 4 (15.4) | .555 |

| Palpitations | 4 (30.8) | 5 (19.2) | .420 |

| Chest pain | 7 (53.8) | 4 (15.4) | .012 |

| NSVT | 3 (23.1) | 7 (26.9) | .795 |

| ABPR | 1 (7.7) | 5 (19.2) | .346 |

| Number of risk factors* | |||

| 0 | 2 (15.4) | 7 (26.9) | .420 |

| 1 | 8 (61.5) | 13 (50.0) | .496 |

| 2 | 1 (7.7) | 3 (11.5) | .709 |

| ≥3 | 2 (15.4) | 3 (11.5) | .735 |

| Mean number of risk factors | 1.4±1.3 | 1.1±0.9 | .406 |

| Risk prediction model O’Mahony | 3.2±3.8 | 3.4±2.0 | .858 |

| >4% | 2 (15.4) | 8 (30.8) | .300 |

| >6% | 1 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) | .608 |

| Events (follow-up) | |||

| Sudden death | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | .474 |

| Resuscitation cardiac arrest | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| ICD discharge | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.6) | .304 |

| Combined SD/CA/ICD discharge | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.5) | .202 |

| Heart failure death | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| Transplant | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | .040 |

| Stroke | 2 (15.4) | 3 (11.5) | .735 |

ABPR, abnormal blood pressure response during upright exercise; ASH, asymmetrical septal hypertrophy; CA, cardiac arrest; ECG, electrocardiogram; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEDd, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; LVH, left ventricular wall thickness; LVNC, left ventricular non compaction; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on Holter monitoring; NYHA, New York Heart Association dyspnea class; SD, sudden death.

Severe LVH: if maximal LVH ≥ 30mm; obstruction: left ventricular outflow tract gradient (> 30mmHg); severe obstruction: if left ventricular outflow tract gradient ≥ 90mmHg; pattern 2: morphological subtype of hypertrophy according to McKenna et al.13; left atrium: left atrial diameter (mm); Henry (%): percentage of expected left ventricular end diastolic diameter; chest pain: exertional chest pain.

The results are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Most patients had moderate to severe hypertrophy (20.1±6.7mm), 4 with hypertrophy>30mm, who were male. One carrier exhibited features consistent with left ventricular noncompaction. Thirteen carriers had limiting symptoms (New York Heart Association [NYHA] dyspnea class III-IV) and 14 carriers developed systolic impairment. Atrial fibrillation was present in 41.0%.

Patients with HCM were more frequently male (P=.005). Female patients had a significantly later onset of the disease but they were more symptomatic (NYHA III-IV [53.8% vs 23.1%, P=.055] and more frequently had and chest pain [P=.012]) than male patients. The pattern of hypertrophy, the electrocardiogram and the risk profile showed no differences between the sexes.

Family genetic testing identified 54 carriers (29 men) and 42 noncarriers, while DNA samples were not available in 11 relatives. Thirty-nine carriers (72.2%) had HCM, 2 (3.7%) were considered to be possibly affected, and 13 (24.1%) were considered clinically unaffected.

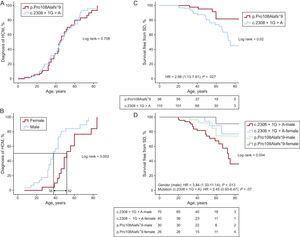

Disease penetrance was greater as age increased, with a 50% chance of being diagnosed with the disease at the age of 44 years (Figure 1A). Men tended to develop the disease earlier than women (there was a 50% probability of developing HCM at age 38 years for men and at age 52 years for women, P=.002) (Figure 1B).

A: penetrance of the disease (HCM) in carriers of 2 mutations: p.Pro108Alafs*9 vs c.2308+1G>A. B: penetrance of disease (HCM) in carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9. C: survival free from SD/ICD discharge in 2 groups of carriers of different mutations. D: survival free from sudden death in carriers of either of the 2 mutations by sex. For A and B, all 54 carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9 (39 affected, 2 possibly affected and 13 unaffected) and 86 carriers of c.2308+1G>A (61 affected and 25 unaffected) were included. For C and D, 53 living carriers and 3 SD cases (2 historic SD, 1 SD) with p.Pro108Alafs*9 and 90 living carriers and 20 SD cases (17 historic SD, 2 resuscitated cardiac arrest, 1 SD) with c.2308+1G>A were included. Two appropriate ICD discharges from the first group and 4 from the second were considered as SD equivalent for the purpose of the survival analysis. The total number of individuals included in the analysis was 166 (“Methods” of the ). HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; SD, sudden death.

There were a total of 5 cases of sudden death (SD)/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) discharge (2 historical, 1 SD, 2 appropriate ICD discharges) (50±13 years, 3 men) in the 13 families with the mutation (3 with a definitive diagnosis of HCM). The cohort was followed up for a mean of 72±53 months. The single patient who died suddenly during follow-up was a 57-year-old man with a family history of sudden cardiac death and 2 syncopal episodes. He had 20-mm obstructive LV hypertrophy with limiting symptoms (NYHA IV). Two female patients underwent heart transplant. There were 5 patients with stroke (mean age 60±15 years, 3 men).

Comparison of the Phenotype Caused by MYBPC3 Truncating MutationsThe HCM phenotype was compared in 2 groups of patients carrying 2 different mutations; both of these mutations altered full-length MYBPC3 (Figure 2). The clinical characteristics of the 39 affected carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9 were compared with those of the 61 affected carriers of c.2308+1G>A (Table 2).

Comparison of the Clinical Characteristics in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Affected Carriers of One of the Two Most Prevalent Mutations in our Region: p.Pro108Alafs*9 vs c.2308+1G>A

| p.Pro108Alafs*9 | c.2308+1G>A | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 39 (39.0) | 61 (61.0) | 100 (100.0) | |

| Male sex | 26 (66.7) | 43 (70.5) | 69 (69.0) | .687 |

| Age, y | 55.5±17.7 | 52.9±17.3 | 53.9±17.4 | .471 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 43.2±17.0 | 42.3±17.6 | 42.7±17.4 | .816 |

| Reason for diagnosis | ||||

| Incidental | 8 (21.1) | 9 (15.0) | 17 (17.3) | .441 |

| Family screening | 16 (42.1) | 24 (40.0) | 40 (40.8) | .836 |

| Symptoms | 14 (36.8) | 27 (45.0) | 41 (41.8) | .425 |

| Hypertension | 15 (38.5) | 21 (34.4) | 36 (36.0) | .261 |

| Abnormal ECG | 29 (74.4) | 55 (90.2) | 84 (84.0) | .035 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 (41.0) | 18 (29.5) | 34 (34.0) | .236 |

| Maximal LVH, mm | 20.1±6.7 | 20.9±5.6 | 20.6±6.0 | .506 |

| Severe LVH, mm | 4 (10.3) | 5 (8.2) | 9 (9.0) | .726 |

| LVNC | 1 (2.6) | 3 (4.9) | 4 (4.0) | .558 |

| Obstruction | 10 (25.6) | 15 (24.6) | 25 (25.0) | .906 |

| Severe obstruction | 5 (15.4) | 6 (10.0) | 12 (12.1) | .422 |

| Pattern | ||||

| No hypertrophy | 1 (3.8) | 2 (3.3) | 3 (3.5) | .905 |

| ASH | 16 (61.5) | 45 (75.0) | 61 (70.9) | .207 |

| Concentric | 6 (23.1) | 8 (13.3) | 14 (16.3) | .261 |

| Apical | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.2) | .508 |

| Left atrium, mm | 44.8±8.3) | 43.7±6.1 | 44.1±7.0 | .467 |

| LVEDd, mm | 45.1±6.7 | 43.7±7.2 | 44.2±7.0 | .346 |

| Systolic impairment | 14 (40.0) | 26 (44.1) | 40 (42.6) | .7 |

| Diastolic function | ||||

| Pseudonormal | 4 (20.0)b | 24 (44.4)b | 28 (37.8)b | .054 |

| Restrictive | 0 (0.0)b | 2 (3.7)b | 2 (2.7)b | .383 |

| Mitral regurgitation III-IV | 5 (12.8) | 2 (3.3) | 7 (7.0) | .068 |

| NYHA III-IV | 13 (33.3) | 17 (27.8) | 30 (30.0) | .560 |

| Syncope | 5 (16.1) | 8 (14.3) | 13 (14.9) | .817 |

| Palpitations | 8 (25.8) | 15 (26.8) | 23 (26.4) | .921 |

| Chest pain | 9 (29.0) | 8 (14.3) | 17 (19.5) | .097 |

| NSVT | 10 (25.6) | 22 (36.1) | 32 (32.0) | .276 |

| ABPR | 6 (15.4) | 12 (19.7) | 18 (18.0) | .586 |

| ICD implanted | 4 (10.3) | 16 (26.2) | 20 (20.0) | .051 |

| Number of risk factorsa | ||||

| 0 | 9 (23.1) | 10 (16.4) | 19 (19.0) | .406 |

| 1 | 21 (53.8) | 24 (39.3) | 45 (45.0) | .155 |

| 2 | 4 (10.3) | 17 (27.9) | 21 (21.0) | .035 |

| ≥3 | 5 (12.8) | 10 (16.4) | 15 (15.0) | .626 |

| Mean number of risk factors | 1.20±1.10 | 1.50±1.10 | 1.38±1.10 | .142 |

| Mean risk prediction model O’Mahony | 3.3±2.7 | 4.6±4.4 | 4.0±3.8 | .112 |

| >4% | 10 (25.6) | 7 (11.5) | 17 (17.0) | .066 |

| >6% | 2 (5.1) | 12 (19.7) | 14 (14.0) | .041 |

| Events (follow-up) | ||||

| Sudden death | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2.0) | .747 |

| Resuscitation cardiac arrest | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.0) | .253 |

| ICD discharge | 2 (5.2) | 4 (6.6) | 6 (6.0) | .769 |

| Combined SD/CA/ICD discharge | 3 (7.8) | 7 (11.5) | 10 (10.0) | .538 |

| Heart failure death | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.6) | 4 (4.0) | .103 |

| Transplant | 2 (5.2) | 1 (1.6) | 3 (3.0) | .318 |

| Composite cardiac | 5 (12.8) | 12 (19.7) | 17 (17.0) | .374 |

| Stroke | 5 (12.8) | 3 (4.9) | 8 (8.0) | .155 |

ABPR, abnormal blood pressure response during upright exercise; ASH, asymmetrical septal hypertrophy; CA, cardiac arrest; ECG, electrocardiogram; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEDd, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; LVH, left ventricular wall thickness; LVNC, left ventricular non compaction; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on Holter monitoring; NYHA, New York Heart Association dyspnea class; SD: sudden death.

The results are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

(0-6). Risk factors of sudden death were considered: NSVT, ABPR if age<45 years of age, family history of sudden death, syncope, severe LVH and severe gradient (> 90mmHg).

From available. Severe LVH, if Max LVH ≥ 30mm; obstruction: left ventricular outflow tract gradient (>30mmHg); severe obstruction: if left ventricular outflow tract gradient ≥ 90mmHg; pattern 2: morphological subtype of hypertrophy according to McKenna et al.13; left atrium: left atrial diameter (mm); Henry (%): percentage of expected left ventricular en diastolic diameter; Chest Pain: Exertional chest pain; composite cardiac: cardiac death (SD, heart failure death), cardiac arrest, ICD discharge and transplant.

The phenotype was similar in c.2308+1G>A and in p.Pro108Alafs*9. However, the proportion of patients with an electrocardiogram characteristic of HCM (55 [90.2%] vs 29 [74.4%]; P=.035), with 2 or more risk factors (27 [44.3%] vs 9 [23.1%]; P=.03) and a SD risk in 5 years of O’Mahony>6% (12 [19.7%] vs 2 [5.1%]; P=.041) were significantly higher in c.2308+1G>A carriers than in p.Pro108Alafs*9 carriers. The number of SD/ICD discharges during follow-up was similar in c.2308+1G>A and in p.Pro108Alafs*9 (7 [11.5%] vs 3 [7.8%]; P=.5).

The development of hypertrophy in the 2 carrier groups was similar over their life span, as reflected by the similarity between the 2 probability shapes of HCM diagnosis. Disease penetrance increased at a regular pace during life from 20 years of age onward, following a sigmoid shape (Figure 1A). When all living patients from the cohort and the SD cases (historical and prospective cases, see “Methods”) were included, SD/ICD discharge survival was significantly lower in the group with the c.2308+1G>A mutation than in the p.Pro108Alafs*9 group. The risk of SC/ICD discharge was higher in the c.2308+1G>A group than in the p.Pro108Alafs*9 group (hazard ratio [HR]=2.98; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 1.13-7.81; P=.02) (Figure 1C).

On Kaplan-Meier analysis, SD/ICD survival was worst in men with c.2308+1G>A and best in women in the p.Pro108Alafs*9 group (Figure 1D). On multivariate analysis, male sex was a predictors of SD/ICD discharge (HR=3.84; 95%CI, 1.33-11.14; P=.013 and there was a trend toward higher risk with the c.2308+1G>A mutation (HR=2.45; 95%CI, 0.93-6.47, P=.07). There were no significant differences in survival free from heart failure (NHYA III-IV) or atrial fibrillation between the 2 groups or by sex (data not shown).

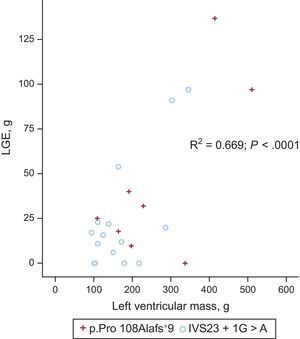

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance CharacterizationTwenty-three patients (8 with p.Pro108Alafs*9 and 15 with c.2308+1G>A) underwent cardiac magnetic resonance study (mean age 44±15 years, 17 men, 6 women). There was a trend toward a higher left ventricular mass in p.Pro108Alafs*9 compared with c.2308+1G>A (mean 269.1±138.4g vs 173.2±80.2g, P=.057, indexed P=.053) (Figure 3). Eighteen (78.3%) patients had late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) (7 [87.5%] p.Pro108Alafs*9 and 11 [73.3%] c.2308+1G>A], P=.9). Patterns of LGE were similar in the 2 groups. There was no significant difference in the fibrosis pattern between the 2 groups. A right-left ventricular junction pattern predominated in carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9 (50.0%) while a septal diffuse pattern predominated in c.2308+1G>A carriers (40.0%). There were no differences in LGE mass and percentage of LGE mass between the groups (39.9±46.8g vs 24.6±31.3g, P=.3; 12.4±11.5% vs 13.9±11.2%, P=.8 for p.Pro108Alafs*9 and c.2308+1G>A respectively) (Figure 4).

The presence of the p.Pro108Alafs*9 was an independent predictor of LV mass (absolute and indexed) (HR=2.31; 95%CI, 4.8-96.1; P=.032 for indexed LV mass). The type of mutation was not a predictor for absolute LGE or percentage of LGE.

Two (8.7%) patients with a cardiac magnetic resonance study had an arrhythmic event (1 resuscitated cardiac arrest and 1 ICD discharge). Both patients were c.2308+1G>A carriers and had a diffuse septal fibrosis pattern of LGE (10% and 33% of LGE from total LV mass).

Six (26.0%) patients had nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on Holter monitoring. Three of them (50.0%) had LGE. The risk score for SD was not associated with the presence of LGE (SD score, 4.2±2.3 vs 3.2±1.6 for absence and presence of LGE respectively; P=.3). Neither nonsustained ventricular tachycardia nor SD risk score was associated with LV mass or LGE variables.

Histological StudyHistopathological study from an explanted heart from a female p.Pro108Alafs*9 carrier showed severe concentric hypertrophy and diffuse interstitial fibrosis (). This patient was diagnosed with HCM at age 44 years. She showed no evidence of obstruction. Echocardiograms prior to transplant revealed a small LV cavity and severe diastolic dysfunction, which was thought to be the cause of the limiting symptoms. Despite medical therapy, she received a transplant when she was 68 years old.

The histological study from a transplanted male c.2308+1G>A carrier demonstrated large transmural and heterogeneous scars (). The patient was diagnosed with HCM when he was 26 years old, with symptoms associated with obstruction. After 23 years of follow-up, he developed systolic dysfunction and received a heart transplant at 49 years of age. Examination revealed a dilated heart with extensive fibrosis, disarray, and hypertrophy.

Apart from a couple of illustrative cases, the attractive hypothesis that carriers of a malignant mutation would develop a particular pattern of fibrosis could not be demonstrated from cardiac magnetic resonance results.

MYBPC3 Truncating MutationsTo investigate which transcripts were produced by c.2308+1G>A and to determine whether the truncated transcripts were degraded by nonsense-mediated RNA decay, lymphocytes of carriers of 2 mutations were cultured with the translation inhibitor puromycin.

c.2308+1G>A is a G>A transition in the 3 prime splice donor site of intron 23 of MYBPC3 that inactivates this splicing site. This mutation produced alternative splice donor sites, resulting in 2 transcripts of longer sizes (4515 and 4761 pb) than wildtype (4217 pb) when lymphocytes were cultured with puromycin. Nevertheless, only the wildtype allele was shown when lymphocytes were cultured without puromycin, indicating that aberrant transcripts generated by this variant were degraded independently of their lengths. The same occurred when we analyzed the messenger RNA of a p.Pro108Alafs*9 carrier; the wildtype allele was expressed in blood only.

The p.Pro108Alafs*9 mutation is an insertion of the GCTGGCCCCTGCC nucleotides in position 29 of exon 3. This insertion also produces a frameshift: the aberrant complementary DNA results in 107 normal MYBPC3 residues and then 8 novel amino acids, followed by a premature stop codon in the proline-alanine (Ala-Pro)-rich region. This should produce a large truncated protein of 116 amino acids (-91%) lacking the MYBPC3 motif containing the phosphorylation sites and the titin and myosin binding sites rather than the wildtype protein consisting of 1275 amino acids.

Figure 2 shows distinct previously described mutations in MYBPC3, each of which produce peptides of different lengths.10,11,14–17 Penetrance varies from 62% to 82% with no association with the position of the mutation in MYBPC3. On the contrary, a trend toward an increased prevalence of SD proportional with the length of the transcript can be seen, being 13% for the shortest (p.Pro108Alafs*9) and maximum (67%) for the second longest (IVS20-2A>G). The longest Q1061* does not fit with the rest and the prevalence of SD is low.

In Silico StudyThe pathogenicity of p.Pro108Alafs*9 was studied using the modified criteria used previously by Van Spaendonck-Zwarts et al.18 A list of mutation-specific features based on in silico analysis with the mutation interpretation software MutationTaster and the frecuency in a control population predicted this variant as disease causing with a probability of 1.19 Familial study was required to study the cosegregation and finally to classify the variant as pathogenic.

DISCUSSIONClinical Phenotype of p.Pro108Alafs*9In the present study, we describe a novel mutation identified in 54 carriers from 13 families. Overall, 72% of our carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9 had HCM. Our study confirms the association between the p.Pro108Alafs*9 mutation in the MYBPC3 gene and the development of HCM with a family cosegregation of 100%.

Patients affected by p.Pro108Alafs*9 are characterized by asymmetric septal hypertrophy with the presence of obstruction in approximately 25%, a high penetrance, and middle age at disease onset (43±17 years old). Heart failure symptoms are predominant while SD is a rare complication.

In keeping with the literature, our carrier patients exhibited an age-related penetrance,20 with similar shapes for both mutations. Interestingly, and according to 2 other reported series10,21 there was a clear male predominance in affected carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9, who were also younger than the women at diagnosis. However, differences in penetrance and a delay in the onset of disease between the sexes have not been demonstrated in large populations of patients with HCM.15,22–24

Similar to other series, most affected carriers were in NYHA class I-II, less than 20% reported syncope, and less than 30% had chest pain.25 On average, the women were in a worse NYHA functional class and more frequently had chest pain. The percentage of patients with atrial fibrillation in our series (41%) was higher than that reported by other authors.24,26

Phenotypical Comparison Between the Two MutationsThis report describes the comparison of the phenotypical characteristics of the 2 most prevalent mutations found in our region, p.Pro108Alafs*9 and c.2308+1G>A. This latest series includes one of the largest with the same mutation in MYBPC3 reported to date.10 p.Pro108Alafs*9 was also a founder mutation in our cohort but, in contrast with c.2308+1G>A, it produced a lower rate of arrhythmic events in the affected patients. Survival free from SD/ICD discharge (historical and prospective) was clearly lower in c.2308+1G>A than in p.Pro108Alafs*9. Other founder mutations have been described in MYBPC3 located in different regions predicting a C-terminal truncated protein due to a premature termination codon, although each expresses a different phenotype.11,12,14–17,27,28 Dominant mutations are generally responsible for negative selection pressure and tend to disappear after several generations. Some of these mutations, such as c.2308+1G>A, escape this selection pressure and are transmitted over generations because disease expression is delayed beyond reproductive age.16

The results of genotype-phenotype correlation studies in HCM have been confounded by the small size of the families, the low frequency of each casual mutation (< 5%), and the small number of families with identical mutations.29 Generally, MYBPC3 mutations are associated with a later average age at symptom onset, a lower incidence of SD, and a relatively benign clinical course, although no differences in clinical phenotype have been attributable to the specific type of MYBPC3 mutation.30 Therefore, the high prevalence of these founder mutations provides an opportunity to define their clinical profiles.

Length of the Transcript and PhenotypeThe nonsense-mediated decay pathway is a messenger RNA surveillance system that typically degrades transcripts containing premature termination codons to prevent the translation of unnecessary or aberrant transcripts. A relatively milder phenotype may be caused by nonsense mutations that activate the nonsense-mediated decay, thereby reducing dominant-negative expression and resulting in haploinsufficiency.20,31,32 It is known that truncated cMYBPCs are preferentially degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which may impair the proteolytic capacity of the ubiquitin-proteasome system.33,34

Length of messenger RNA transcript might play a role in the different risk profile of distinct mutations. Important differences have been observed at the cellular level in infected cardiac cells with mutant MYBPC3 regarding the length of the transcript protein: a) overexpression of human truncated cMYBP-Cs in transgenic mice resulted in markedly lower protein levels, being directly correlated to the size of the protein; b) larger proteins are more likely to be incorporated into the sarcomere, and c) smaller proteins are more prone to block the ubiquitin-proteasome system degradation system leading to the formation of truncated protein aggregates and an increase in the cytosolic concentration of other proteins involved in muscle growth and atrophy and apoptosis.33,35 The ubiquitin-proteasome system also plays a role in degradation of β2 adrenergic receptors and ion channels.

Interestingly, the pathogenicity of mutations in titin has recently been associated with the length of the transcript protein.36

We can discern from our results that the length of the transcript does not affect the severity of the hypertrophy or disease penetrance, but there were differences in risk profile and in SD prognosis, which was worse in the longer transcript group. When we analyzed in detail other founder mutations that truncate the MYBPC3 gene, we observed that the number of SD was proportional to the length of transcript, except in the case of p.Gln1061* (P=.081) (Table 2, in “total SD cases/total HCM affected”).

Fibrosis and Sudden Death RiskLate gadolinium enhancement has been associated with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and SD risk profile in HCM.26,37–39 The right-to-LV junction pattern is the most frequent and is believed to have a more benign prognosis than diffuse or transmural patterns.25 Extensive LGE (> 20% or>30% from left ventricular mass) is indicative of a worse arrhythmic substrate.39,40

Although patients with c.2308+1G>A in our study had a significantly worse SD score (SD risk profile obtained from O’Mahony model) and survival free of SD compared with those with p.Pro108Alafs*9, the supposed arrhythmic substrate was not seen in the subgroup of patients who underwent cardiac magnetic resonance study. The degree and pattern of LGE were similar in patients with p.Pro108Alafs*9 and c.2308+1G>A. Moreover, and contrary to what could be expected, LV mass indexed by sex and age was higher in carriers of p.Pro108Alafs*9 than in c.2308+1G>A carriers (P=.032).

CONCLUSIONSThe novel MYBPC3 p.Pro108Alafs*9 mutation is associated with HCM with a high penetrance and onset in middle age. Heart failure symptoms predominate whereas SD is a rare complication. The SD risk in MYBPC3 mutation carriers could be associated with the length of aberrant transcript but this hypothesis should be confirmed in further studies.

FUNDINGThis study was partly funded partly by national grant of Sociedad Española de Cardiología-Fundación Española del Corazón (SEC-FEC/2014). Investigators are part of a cardiovascular research network (RD12/0042/0049,69) and of a Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria both of them from the Carlos III Health Institute-Unión Europea, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, “Una manera de hacer Europa”. M. Sabater-Molina, D. Pascual-Figal and J.R. Gimeno also work at the University of Murcia.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- -

Most founder mutations in MYBPC3 associated with HCM cause a truncated protein. Nevertheless, phenotypic differences and prognosis seems to vary depending on the mutation.

- -

Recently published European Society of Cardiology guidelines promote the use of a formula for the estimation of SD risk in HCM. Two important variables, such as genetic information and fibrosis (late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac magnetic resonance), were not included in the analysis.

- -

We present the results of the analysis and comparison of 2 large patient cohorts carrying 2 distinct truncating mutations in the same gene (MYBPC3), which behave differently. One of them, p.Pro108Alafs*9, is novel and the pathogenicity is definitive. The difference in prognosis could not be explained by the severity of the hypertrophy or by the extent of the fibrosis.

- -

The data presented here and the results from a literature search suggest an association between the length of the transcript and the proportion of SD cases. This hypothesis is in keeping with cellular experiments and findings from pathogenicity studies in other genes.

We sincerely thank the families that kindly agreed to participate in the study.