To study electrical cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation as a potential cause of acute ischemic brain lesions.

MethodsWe performed prospective analysis of 62 consecutive patients (62 [10] years, 16 female). All of them were anticoagulated for at least 3 weeks with an international normalized tatio of 2.69 (0.66). In all cases a magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was performed before and 24h after the cardioversion, including diffusion-weighted sequences. A neurological exploration was also performed before and after the procedure, using the modified Ictus on the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale and the modified Rankin scale. Written informed consent was obtained in all cases.

ResultsOf the 62 patients, 51 (85%) reverted to sinus rhythm. The neurological examination showed no changes after cardioversion. The pre-procedure magnetic resonance imaging showed microvascular disease in 35 (56%), including 2 patients with known cerebrovascular disease, and did not depict new clinically silent ischemic areas after cardioversion.

ConclusionsAfter electrical cardioversion no acute ischemic lesions in the brain nor alteration in the neurological scales were found. Nevertheless, in 35 patients (56%) with persistent atrial fibrillation, the magnetic resonance imaging showed clinically silent ischemic lesions.

Keywords

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in clinical practice, with a high prevalence in the elderly population.1 The risk of thromboembolic events is 5 times greater in patients with AF than in those in sinus rhythm.2, 3 Several studies4 have shown decreased cognitive capacity in patients with AF, with an increased risk of dementia. It is thought that this cognitive decline may be due to silent brain infarcts.5

One of the primary objectives of treatment for AF is to maintain sinus rhythm. The most effective strategy in these cases is direct-current cardioversion.6 If the procedure is programmed, the patient should have been receiving anticoagulation therapy for at least 3 weeks, given the high risk of embolic events if such prophylaxis is not administered.7, 8 Even so, thromboembolic events occur during the procedure in up to 1% according to some series.9 Moreover, we do not know whether small silent brain infarcts may be occurring.10

Currently, the new diffusion-weighted imaging sequences in brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)11 can show small areas of cerebral ischemia in the initial hours after an embolic event, even when asymptomatic.

The aim of this study was to assess new-onset silent ischemic lesions after programmed direct-current cardioversion using diffusion-weighted sequences in brain MRI.

MethodsWe studied 62 patients (16 women) with persistent AF who were scheduled for direct-current cardioversion to revert to sinus rhythm.

The exclusion criteria were clinical instability, carrier of a pacemaker or any metal prosthesis that contraindicated MRI, gadolinium allergy, and claustrophobia.

The study was reviewed and approved by the hospital research ethics committee.

All patients received information in writing about the study and completed an informed consent form.

Study ProtocolAll patients received acenocoumarol at least 4 weeks before the procedure to maintain an international normalized ratio (INR) between 2 and 3. All participants signed an informed consent in accordance with the requirements of the hospital ethics committee.

All patients underwent a complete neurological examination according to the modified Rankin scale and the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), as well as a brain MRI 1 to 2h before cardioversion. The neurological test and brain MRI were repeated 24h later. The results of the neurological examination before and after cardioversion were compared, as were MRI images before and after the procedure.

Cardioversion ProcedureThe study was performed in patients in a fasting state. All patients were sedated with propofol (1mg/kg body weight). The scan was performed with the patient in the anterolateral position with an initial shock of 100J, with QRS gating and a biphasic electrode. If AF persisted, a second shock of 200J was applied. If arrhythmia continued, a shcock of 270J was applied.

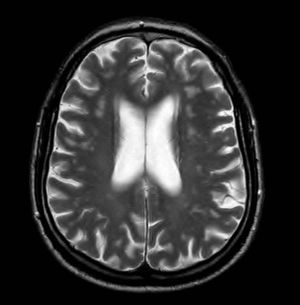

Magnetic Resonance ImagingThe MRI protocol included 2 studies, the first hours before direct-current cardioversion and the second 24h after the procedure, using a 1.5 T system (1.5 T Intera; Philips Medical Systems). Standard sequences were used, including a sagittal T1 morphologic sequence, 2 axial T2-enhanced sequences and FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery), a coronal T2-enhanced sequence, and a diffusion-weighted sequence. The latter used a repetition time of 3100, an echo time of 90ms, and a field of view of 230mm. In total, 22 5-mm slices were recorded with 1mm between slices. A b value of 0 and 1000 was used, and in all cases the apparent diffusion coefficients were mapped. Both the diffusion images and apparent diffusion coefficient maps were assessed for all patients (Figure 1) and the results of these 2 studies performed 24h apart were compared. In doubtful cases, diffusion-weighted images were quantified and compared with the opposite side.

Figure 1. Apparent diffusion coefficient map.

The MRI scans were interpreted independently by 2 neuroradiologists with 8 and 4 years experience, respectively, in the field of neuroradiology.

Statistical AnalysisThis was a descriptive study. Qualitative variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) and discontinuous ones as percentages.

The Student t test was used to assess for significant differences between continuous variables, while the χ2 test was used for discontinuous ones.

ResultsPatient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The distribution according to CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc categories18 is summarized in Table 2, Table 3, respectively.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics

| Age, years | 62±10 |

| Women | 16 (26) |

| Smoking habit | 7 (11.3) |

| Hypertension | 39 (63) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (8) |

| Prior embolism | 3 (4.8) |

| Valve disease | 5 (8) |

| Ischemia | 6 (9.6) |

| More than 1 year in AF | 15 (24) |

| Left atrium | 45±5.5 |

| LVEF, % | 58±8 |

| Heart failure | 10 (16) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2 (3.2) |

| Permanent OAC | 29 (46.8) |

| Aspirin | 22 (35.5) |

| Clopidogrel | 2 (3.2) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OAC, oral anticoagulation.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or no. (%).

Table 2. Patient Distribution According to the CHADS2 Classification

| Score | Patients, no. (%) |

| 0 | 20 (32.3) |

| 1 | 25 (40.3) |

| 2 | 11 (17.7) |

| 3 | 5 (8) |

| 4 | 1 (1.6) |

| Total | 62 (100) |

Table 3. Patient Distribution According to the CHA2DS2VASc Classification

| Score | Patients, no. (%) |

| 0 | 10 (16) |

| 1 | 18 (29) |

| 2 | 15 (24.2) |

| 3 | 11 (17.7) |

| 4 | 5 (9.1) |

| 5 | 2 (3.2) |

| 6 | 1 (1.6) |

| Total | 62 |

Of the 62 patients, 51 (85%) reverted to sinus rhythm. The neurological examination was normal in 61 patients, with a score of 0 in the NIHSS and modified Rankin scale, both before and after cardioversion. One patient with a known history of resected meningioma had a score of 4 on the NIHSS and 0 on the modified Rankin scale, with no changes observed in the examination after cardioversion.

In the MRI prior to cardioversion, microvascular ischemic lesions were found in 35 (56.4%) patients. However, no new MRI lesions were observed after cardioversion.

In a secondary analysis, we investigated whether there was a relationship between ischemic lesions found in the baseline MRI and the clinical characteristics of the patients (Table 4).

Table 4. Clinical Characteristics According to Findings in Baseline Magnetic Resonance Imaging

| Clinical characteristics | MRI with ischemia | MRI without ischemia | P |

| Age, years | 65±9 | 58±11 | .015 |

| Men | 27 (77.1) | 19 (73.1) | |

| Women | 8 (22.9) | 7 (26.9) | .770 |

| Smoking habit | 4 (11.4) | 3 (11.5) | 1 |

| HT | 22 (62.9) | 16 (61.5) | 1 |

| Valve disease | 4 (11.4) | 1 (3.8) | .382 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (8.6) | 2 (7.7) | 1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (46.2) | 12 (46.2) | .186 |

| Prior embolism | 1 (2.9) | 2 (7.7) | .570 |

| Ischemia | 4 (11.4) | 2 (7.7) | 1 |

| Permanent OAC | 17 (48.6) | 11 (42.3) | .795 |

| Vascular disease | 1 (3.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 |

| Heart failure | 7 (20) | 3 (11.5) | .494 |

| Aspirin | 15 (42.9) | 7 (26.9) | .282 |

| Clopidogrel | 2 (5.7) | 0 | .503 |

HT, hypertension; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OAC, oral anticoagulation.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or no. (%).

The only statistically significant risk factor for ischemic lesions in the baseline MRI was age (P<.05).

DiscussionIn the present study, there were no clinically observable ischemic events after direct-current cardioversion. We ensured that the patients had an INR between 2 and 3 for at least 3 weeks. There were no new clinically silent brain lesions in the MRI.

Diffusion-weighted MRI has been shown to be every effective for detecting silent ischemia in other situations in which the risk of cardiac embolism is high.12, 13

In different series of patients undergoing pulmonary vein ablation, silent infarcts were observed in between 1% and 2%,14, 15 although in these cases the procedure was more aggressive and oral anticoagulation was withdrawn a few days earlier to be replaced by low-molecular-weight heparins.

Some cases have been reported of patients undergoing direct-current cardioversion in which silent ischemia is detected by intracraneal Doppler measurements.16 It is, however, a less sensitive and specific technique. The new diffusion-weighted brain sequences allow detection of acute ischemia in a 48-h period with a high diagnostic yield.

The high percentage of patients who have microvascular disease in the MRI prior to the procedure is noteworthy. The aim of this study was not to correlate these lesions with associated risk factors, such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, structural heart disease, or peripheral artery disease. However, these findings prompted us to investigate whether we should consider anticoagulation when there are ischemic lesions in the MRI in patients with a low risk of symptomatic embolism according to clinical criteria.10, 17, 18

The present study has several limitations. The first is the low number of patients. In addition, the fact that it was a single-center study means that we cannot extrapolate to the general population.

Our findings might also be somewhat unreliable given that we did not record any events. However, the study is a reflection of clinical practice when undertaking a scheduled direct-current cardioversion.

However, our results do suggest that we can avoid thromboembolic events, including clinically silent ones, by being strict with oral anticoagulation before undertaking a scheduled electric cardioversion.

ConclusionsIn our series, we did not detect acute ischemic lesions after direct-current cardioversion through brain MRI diffusion sequences in a series of 62 patients with persistent AF who were receiving anticoagulation therapy. Appropriate anticoagulation therapy for at least 4 weeks, with an INR between 2 and 3, allows direct-current cardioversion to be performed safely. In addition, we observed that a high percentage of patients with AF had microvascular disease, although without any clinical repercussions.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Received 9 May 2011

Accepted 17 August 2011

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Povisa, Salamanca 5, 36211 Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain. macrisvc@yahoo.es