Beta-blockers are widely used molecules that are able to antagonize β-adrenergic receptors (ARs), which belong to the G protein-coupled receptor family and receive their stimulus from endogenous catecholamines. Upon β-AR stimulation, numerous intracellular cascades are activated, ultimately leading to cardiac contraction or vascular dilation, depending on the relevant subtype and their location. Three subtypes have been described that are differentially expressed in the body (β1-, β2- and β3-ARs), β1 being the most abundant subtype in the heart. Since their discovery, β-ARs have become an important target to fight cardiovascular disease. In fact, since their discovery by James Black in the late 1950s, β-blockers have revolutionized the field of cardiovascular therapies. To date, 3 generations of drugs have been released: nonselective β-blockers, cardioselective β-blockers (selective β1-antagonists), and a third generation of these drugs able to block β1 together with extra vasodilation activity (also called vasodilating β-blockers) either by blocking α1- or by activating β3-AR. More than 50 years after propranolol was introduced to the market due to its ability to reduce heart rate and consequently myocardial oxygen demand in the event of an angina attack, β-blockers are still widely used in clinics.

Keywords

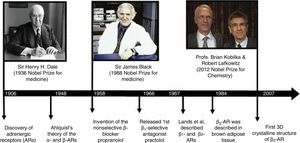

From a classic pharmacological point of view, beta-blockers (or β-blockers) are antagonists of β-adrenergic receptors (ARs), which play an important role in the control of physiological processes such as blood pressure, heart rate and airway strength or reactivity, as well as other metabolic and central nervous system processes.1–4 After their discovery by Nobel prize-winner, Sir Henry H. Dale in 19065 (Figure 1), ARs became key targets in cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension and heart failure (HF), in respiratory diseases such as asthma, and other no less important diseases, such as benign prostatic hypertrophy, nasal congestion, obesity, and pain, among many others.1–4

However, it was not until 1948 that Raymond P. Ahlquist observed 2 differentiated pathways inducing pharmacological responses depending on the organ in which the drugs were studied. Based on these experiments, Ahlquist divided ARs into 2 types, the α-ARs (associated with most “excitatory” functions such as vasoconstriction) and β-ARs (associated with most “inhibitory” functions, including vasodilation, and 1 “excitatory” effect, stimulation of the myocardium).6 Later on, in 1958, Sir James Black introduced the first β-blocker in the search for a treatment able to reduce oxygen consumption in the event of an angina attack, and corroborated Ahlquist's theory. This invention, considered one of the most important achievements in medicine in the 20th century, gained Black and the world of ARs a second Nobel prize in 19887 (Figure 1).

In 1967, Alonzo M. Lands and his collaborators proposed the division of β-ARs into 2 different subtypes: β1-ARs, mostly present in heart, and β2-ARs, responsible for vascular and airway relaxation.8 This classification was supported by the subsequent discovery of selective antagonists for β1-ARs.9 Very soon a third subtype with as many similarities as differences, insensitive to the most commonly used drugs, was identified in the cells of brown adipose tissue from rats and named β3-AR.10,11

The latest milestone was achieved by Robert J. Lefkowitz and Brian K. Kobilka, who helped to identify the interaction of β-ARs with cell structures, their dynamic regulation and desensitization and finally to solve the β2-AR 3-dimensional crystalline structure in 2007 (Figure 1). This work led to Lefkowitz and Kobilka being awarded the third Nobel prize for work on ARs in 2012.12

History, development, and classification of β-blockersIn 1958, Sir James Black had the brilliant idea of targeting a reduction in myocardial oxygen demand, instead of an increase in its availability by vasodilation, in the event of an angina attack. Inspired by Ahlquist's theory, Black's obsession was to find a drug that was able to block the “excitatory” effect attributed to β-AR on the myocardium, thus controlling heart rate. In the meantime, Eli Lilly Laboratories released dichloroisoproterenol, which had been thought to be a bronchodilator, but which showed certain antagonistic effects on the heart.13 After learning about these works, Black came up with the idea of synthesizing dichloroisoproterenol analogs that could be more potent and selective in their β-adrenergic blockade properties. In this search, he invented the first β-blocker approved for use in clinics, propranolol.14 Propranolol is the prototype of the first generation of β-blockers, which are drugs that have similar affinities for β1 and β2-AR (Table 1),15-32 and for this reason, are considered to be “nonselective β-blockers”. Among this group, propranolol is the drug with the most accumulated clinical experience and indications33 (Table 2).

Classification and mechanism of action of beta-blockers

| β-adrenergic receptors | Complementary mechanisms | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy | |||||||||||

| Affinity (pKD)15–19 | β1 | β2 | β3 | ||||||||

| β1 | β2 | β3 | cAMP | ERK | cAMP | ERK | cAMP | ||||

| β1-β2 selective | No vasodilatory activity | Alprenolol | 7.8-8.2 | 8.9-9.0 | 6.9-7.4 | IA16 | PA20,a | IA21PA22 | PA22 | PA16 | |

| Bupranolol | 8.5 | 9.8 | 7.0 | Ant23 | |||||||

| Carazolol | 9.7 | 10.5 | 8.4 | PA17 | Ant15 | PA15 | |||||

| Nadolol | 7.2 | 8.6 | 6.2 | IA22 | |||||||

| Oxprenolol | 7.9 | 8.9 | 6.3 | PA17 | Ant15PA22 | PA22 | PA15 | ||||

| Pindolol | 8.6 | 8.3-9.2 | 7.0-7.4 | PA17IA16 | PA15,22IA16,21 | PA22 | PA15,16 | ||||

| Propranolol | 8.16-8.75 | 8.44-9.08 | 6.73-6.93 | IA16,24 | PA24 | IA16,21,22,24Ant25 | PA22,24,26 | Ant16 | |||

| Sotalol | 5.77 | 6.85 | 5.05 | IA22 | K+ channels27 | ||||||

| Timolol | 8.27 | 9.68 | 6.80 | IA 21,22,25 | PA26 | ||||||

| Vasodilatory activity | Carvedilol | 8.75-9.26 | 8.96-10.06 | 6.61-8.30 | PA23,24,28IA16 | PA20,a,23,24,29,b | Ant24IA16,22 | PA22,24 | Ant16 | α1-AR antagonism30NO release | |

| Labetalol | 7.63-7.99 | 8.03-8.25 | 6.18 | PA23,24,28 | Ant24 | PA22,24 | PA22,24 | α1-AR antagonism31 | |||

| β1-selective | No vasodilatory activity | Acebutolol | 6.46-6.57 | 6.08-5.70 | 4.41 | PA23,24,28 | PA22 | PA22 | |||

| Atenolol | 6.41-6.66 | 5.09-5.99 | 4.11-4.19 | Ant23IA16,24 | Ant24 | IA16,24PA22 | IA24PA22 | PA16 | |||

| Betaxolol | 8.21 | 6.24-7.38 | 5.97 | IA21,22,25 | |||||||

| Bisoprolol | 7.43-7.98 | 5.42-6.70 | 5.04-5.67 | IA16,24,28 | Ant24 | IA16,22,24 | IA24 | Ant16 | |||

| Metoprolol | 7.26-7.36 | 5.49-6.89 | 5.00-5.16 | IA16,24,28 | Ant24 | IA16,22,24 | IA24 | Ant16 | |||

| Xamoterol | 7.08-7.22 | 5.79-6.07 | 4.45 | PA28 | |||||||

| Vasodilatoy activity | Celiprolol | 6.92 | 5.08 | ND | PA18 | α2-AR18 | |||||

| Nebivolol | 8.79-9.17 | 6.65-7.96 | 5.66-7.04 | Ant17,28 | PA32,a | Ant15 | Ant15 | NO release19 | |||

Ant, antagonism; AR, adrenergic receptor; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IA, inverse agonism; ND, not determined; pKD, log drug concentration that binds 50% of the receptor population (constant expressing affinity); PA, partial agonism.

Most common indications of β-blockers

| β1-β2 selective | β1-selective | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No vasodilatory activity | Vasodilatory activity | No vasodilatory activity | Vasodilatory activity | |||||||||

| Heart failure | Carvedilol | Bisoprolol | Metoprolol | Nebivolol | ||||||||

| Hypertension | Propranolol | Nadolol | Carvedilol | Labetalol | Atenolol | Bisoprolol | Metoprolol | Celiprolol | Nebivolol | |||

| Ocular hypertension | Timolol | Betaxolol | ||||||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | Propranolol | Nadolol | Carvedilol | Atenolol | Bisoprolol | Metoprolol | Celiprolol | |||||

| Arrhythmia | Propranolol | Nadolol | Sotalol | Atenolol | Metoprolol | |||||||

| Portal hypertensive bleeding (prophylaxis) | Propranolol | Carvedilol | ||||||||||

| Migraine (prophylaxis) | Propranolol | Nadolol | Metoprolol | |||||||||

| Thyrotoxicosis | Propranolol | Metoprolol | ||||||||||

| Pheocrhomocytoma | Propranolol | |||||||||||

| Essential tremor | Propranolol | |||||||||||

| Anxiety | Propranolol | |||||||||||

A few years later, in 1966, in the search for derivatives able to escape from the bronchoconstriction effect of propranolol in patients with asthma (due to their β2-antagonist activity), the team at Imperial Chemical Industries released practolol, the first compound representative of the second generation of β-blockers, which are drugs exhibiting a higher affinity for β1 than for β2-AR, and are considered as “β1-selective β-blockers” or “cardioselective β-blockers” due to the predominant presence of the β1 subtype in the heart. In 1975, practolol was withdrawn from the market, and the subsequent course of drug development brought new cardioselective β-blockers into the arena. The most representative drugs in this group are atenolol and metoprolol34,35 (Table 1 and Table 2).

The third generation of β-blockers are drugs with additional vasodilating properties and, due to this feature, were named “vasodilating β-blockers”. This vasodilator activity is beneficial because it reduces peripheral vascular resistance while maintaining or improving cardiac output, stroke volume, and left ventricular function. Compounds belonging to this group can be selective or nonselective for β1-AR but exhibit additional mechanisms, such as α1-AR antagonist activity (carvedilol and labetalol) and nitric oxide (NO) release (nebivolol), explaining their vasodilatory activity. Additionally, vasodilating β-blockers have neutral (labetalol and nebivolol) or beneficial (carvedilol) effects on glucose and lipid metabolism, whereas most clinical studies indicate that nonvasodilating-blockers tend toward having a negative effect on glucose and lipid parameters36 (Table 1 and Table 2).

This emerging field has been completed with long-acting and ultra-short formulations, which have helped improve the therapeutic arsenal.34,35

Today, there is no doubt that the introduction of β-blockers more than 50 years ago revolutionized human pharmacotherapy and had a positive impact on the health of millions of people with cardiovascular and noncardiovascular diseases.

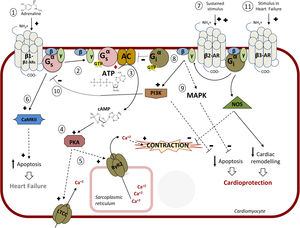

CARDIAC β-ADRENERGIC RECEPTORS: SIGNALING PATHWAYS AND MODULATIONA better knowledge of the complex signaling networks triggered downstream of β-AR stimulation and of their alterations in pathological conditions is key for understanding the effects of β-blockers and for the design of therapeutic strategies. The 3 subtypes of β-ARs (β1-AR, β2-AR, β3-AR) are present in cardiac tissue. While all β-ARs belong to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily of membrane receptors and share several structural and functional features, the 3 subtypes display different affinities for given ligands, specific cellular expression and subcellular localization patterns, differential coupling to signaling cascades, and distinct regulatory mechanisms2,3,37 (Figure 2).

Intracellular pathway mediated by β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs). 1: Main pathway: catecholamines bind to β-adrenoceptors inducing coupling to the heterotrimeric Gs protein; 2: Dissociation of the Gαs-GTP subunit and activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC); 3: Synthesis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP); 4: protein kinase A (PKA) activation; 5: Coordinated phosphorylation of various targets by PKA, including the plasma membrane L-type calcium channel (LTCC) or the RyR2 calcium channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, results in increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentration available for contraction of cardiac muscle. 6: Continuous stimulation (as described in chronic heart failure) of β1-AR induces apoptosis via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) leading to apoptosis and heart damage. 7: Continued stimulation of β2 (increased when using selective β1-blockers) induces coupling to Gi protein; 8: AC is inhibited by the Gα-GTP subunit of Gi; 9: The Gβγ subunit of Gi induces both the inhibition of apoptosis (via stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases [MAPK] and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K]-protein kinsase B [AKT] pathway) and of Gs-mediated deleterious effects (10), leading to cardioprotection. 11: In heart failure, stimulation of the β -adrenoceptor might lead to cardioprotection and a reduction in cardiac remodeling via nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activation. Adapted with permission from Watson et al.37.

Upon agonist binding, GPCRs couple to heterotrimeric G proteins, thus facilitating exchange of GDP by GTP in the Gα subunits, which subsequently dissociate from the βγ dimers. Free Gα and βγ subunits transiently interact with effectors (such as adenylyl cyclases or phospholipases, among others) to trigger signal transduction cascades.4 In addition, agonist-activated GPCRs are specifically phosphorylated in the third cytoplasmic loop and/or the C-terminal tail by GPCR kinases (GRKs), a family of 7 serine/threonine protein kinases.38,39 Subsequently, cytosolic protein β-arrestins are recruited to the phosphorylated receptor, leading to uncoupling from G proteins, a process termed GPCR desensitization. In addition, β-arrestins can act as a scaffold for proteins of the endocytic machinery and for many other signal transduction partners, thus triggering clathrin-mediated receptor internalization and recycling and a second wave of G protein-independent transduction cascades.40 Therefore, the overall cellular effects of GPCR stimulation would result from the balance between the G protein-dependent and GRKs/β-arrestin-dependent branches of GPCR signaling.

The β-adrenergic/Gαs /PKA signaling axisMyocardial β-ARs modulate cardiac contractility and relaxation via protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of a variety of Ca2+ handling proteins and myofilament components. In physiological conditions, these effects mostly involve β1-AR and β2-AR, since these receptors are predominantly expressed in healthy human cardiomyocytes (with a 4:1 β1-AR to β2-AR ratio), with scarce expression of β3-AR.2,3 Interestingly, in individual ventricular myocytes from mice, β1-ARs appear to be present in all cardiomyocytes, whereas β2-AR and β3-AR are detected in only 5% of myocytes but are abundant in cardiac endothelial cells, where in turn β1-AR is expressed at a low level,41 suggesting a heterogeneous integration of β-AR subtype signaling in different cardiac cells (Figure 2).

Both β1-AR and β2-AR can couple to Gs protein. The activation of the Gαs subunit leads to activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), which in turn catalyzes the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) from adenosine triphosphate (ATP). AC 5 and 6, able to be activated by Gαs and deactivated by Gαi and calcium, are the predominant heart AC isoforms.42 Local increases in cAMP trigger PKA activation by binding to its regulatory subunits, thus releasing the functional catalytic subunit, which coordinately phosphorylates a variety of substrates in different subcellular locations. Phosphorylation of the plasma membrane L-type calcium channel (LTCC) increases Ca2+ influx, which in turn activates the ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane through a mechanism termed Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, resulting in increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentration available for contraction (Figure 2). This process of diastolic SR Ca2+ release is further reinforced via either direct PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RYR2 or indirect calcium-calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) stimulation of this SR channel. In parallel, phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I and cardiac myosin binding protein C facilitates excitation-contraction coupling. On the other hand, PKA phosphorylates and inhibits phospholamban, an inhibitor of SR-Ca2+-ATPase, therefore accelerating cytoplasmic Ca2+ reuptake in the SR and accounting for relaxation. In addition to these inotropic and lusitropic effects, adrenergic stimulation also promotes direct cAMP modulation of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels that carry the pacemaker current, raising heart rate (chronotropic effect).42–44

It is worth noting that β-ARs and their effector pathways targeting Ca2+ handling proteins are highly compartmentalized in cardiomyocytes. β2-AR signaling is more locally confined, since these receptors are preferentially present at T-tubules where they colocalize with LTCC in caveolae, whereas β1-AR globally distribute across T-tubules and sarcolemma and generate cAMP signals that propagate throughout the cell.45 In addition, scaffold proteins termed A kinase-anchoring proteins help to assemble protein complexes including AC, PKA, substrates, and phosphodiesterases at specific subcellular compartments, permitting spatiotemporal regulation of cAMP signaling.42

Besides these mainstream effects, other targets of the β-AR/cAMP/PKA axis may contribute to the overall cellular response. Adrenergic activation of PKA triggers feedback inhibitory mechanisms.4 Both β1- and β2-ARs harbor consensus sequences for PKA phosphorylation, and this event decreases the affinity of these receptors for Gαs, leading to desensitization. PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cardiac β-ARs also induces the recruitment of the cAMP phosphodiesterase-4 to the vicinity of the receptors, thus promoting local degradation of cAMP under prolonged receptor stimulation. Moreover, PKA phosphorylation of the β2-AR favors receptor coupling to Gαi, which helps to further inhibit cAMP production via AC and also triggers alternative signaling pathways, such as the Gβγ/PI3K/protein kinsase B (Akt) cascade.3 In addition to controlling balanced cAMP homeostasis, phosphorylation of β1-AR by PKA favors its interaction with 14-3-3ɛ and thus recruits this protein away from Kv11.1 channels, key regulators of cardiac repolarization and refractoriness,46 whereas PKA can also stimulate the Akt/endothelial NO synthase (eNOS)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/protein kinase G (PKG) cascade, leading to inactivation of LTCC and reduced extracellular Ca2+ influx.44

β-arrestin-dependent pathwaysGRKs and arrestins play a very important role in cardiac β-AR regulation and signaling. GRK2 and GRK5 are expressed in most cardiac cells, while GRK3 is present only in cardiomyocytes. Agonist stimulation sequentially promotes GRK-mediated phosphorylation of β-ARs and recruitment of β-arrestins (β-arrestin1 being more abundant than β-arrestin2 in human hearts), leading to termination of G protein signaling, receptor internalization, and downregulation.47,48 Moreover, β-arrestins initiate signaling cascades independently of G protein activation, such as activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade via interaction with c-Src or transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) upon β1-AR phosphorylation by GRK5.3,49 The latter pathway has been suggested to be cardioprotective, as indicated by augmented apoptosis and cardiac dilation in transgenic mice overexpressing a mutant β1-AR lacking GRK phosphorylation sites and thus unable to recruit β-arrestin and to transactivate EGFR.49 A β1-AR/β-arrestin signaling module also stimulates the processing of protective cardiac miRNAs such as miR-150 and others, protecting the mouse heart from ischemic injury.50 Interestingly, the β-blocker carvedilol, in addition to blocking damaging G protein overactivation, has been shown to act as a β–arrestin-biased β-AR ligand, able to trigger such adaptive β–arrestin-mediated pathways,20,29,50 which opens up interesting avenues of research regarding differential mechanisms of action of β-blockers.

Epac-dependent transduction cascades triggered by cardiac β-ARsBesides PKA, emerging evidence indicates that another cAMP effector, termed Epac (exchange protein activated by cAMP) also plays an important role in β-AR-related cardiac function and pathology. β1-AR-mediated cAMP formation activates Epac1, which in turn activates neuronal NO synthases and CaMKII via PI3K and Akt, thus promoting SR calcium leak via RYR phosphorylation.44,51 The Epac1 signalosome is highly compartmentalized, which may contribute to the functional differences between cardiac β-AR subtypes.

Altered β-AR signaling features in pathological conditionsSympathetic nervous system hyperactivity and enhanced levels of circulating catecholamines are early compensatory mechanisms triggered in response to myocardial damage and dysfunction in order to maintain cardiac output via β–adrenergic-mediated effects in contractility. However, such chronic activation of β-ARs promotes an array of alterations in cardiac signaling networks (including β-AR dysregulation and over-desensitization and altered functionality/expression of GRKs, β-arrestins, and Epac proteins), ultimately contributing to the development of pathological cardiac remodeling, ventricular hypertrophy, fibrosis, arrhythmia, and HF.2,3

Chronic β-AR stimulation is associated with cell apoptosis and the loss of pump function. Selective downregulation of β1-AR expression alters the physiological ratio between β1-AR and β2-AR, which becomes the major β-AR subtype during HF progression.52 Moreover, in this setting, the normal β2-AR localization redistributes from the transverse tubules to a global cell crest and turns into a broad distribution, leading to a more diffuse cAMP signal.53 In failing cardiomyocytes, persistent β2-AR activation also promotes CaMKII-dependent cascades leading to the development of hypertrophy, apoptosis, cardiac dysfunction, and arrhythmias via SR Ca2+overload54 (Figure 2). Redox-inactivation of β1-AR,55 enhanced dosage of prohypertrophic Epac151 or of Gαi, altered levels or S-nitrosylation status of β-arrestins,56 may also contribute to altered β1-AR and β2-AR signaling in pathological settings, as well as antiβ1-AR autoantibodies present in certain patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.57 On the other hand, β3-AR (which is less sensitive to desensitization, can couple to both Gs and Gi proteins and also promotes stimulation of the eNOS/NO/cGMP/PKG axis) appears to be unchanged or even upregulated in pathological contexts. It has been suggested that β1-AR blockade by metoprolol upregulates β3-ARs, leading to the activation of cardioprotective sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling,58 although there are conflicting data on the beneficial role of β3-AR agonists in HF.2

Of note, augmented GRK2 expression has been reported in patients and in experimental models of HF due to chronic hypertensive or ischemic disease and its genetic ablation or inhibition has been shown to be cardioprotective in animal models.52 Increased GRK2 may initially help the myocardium to counteract β-AR overdrive and reduce the risk of tachyarrhythmia, but is maladaptive in the long-term, resulting in β-AR desensitization and downregulation and defective contractility. Enhanced cardiac GRK2 dosage also alters mitochondrial function, compromises NO bioavailability, and promotes cardiac insulin resistance, ultimately fostering maladaptive myocardial remodeling and progression to HF.39,59,60

GRK2 also emerges as a key link to connect cardiac insulin and β-AR cascades in pathological conditions, as this kinase can be upregulated by either catecholamines or a high-fat-diet and can modulate both β-AR and insulin signaling.59,61–64 Interestingly, some β-blockers, as well as exercise, have been reported to reduce myocardial GRK2 levels,2,47 which may contribute to the beneficial effects of these drugs.

β-AR signaling in other cardiac cell typesAlthough most research has focused on the role of adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes, it may also play a very important pathophysiological role in other cardiac cell types.3 In fibroblasts, activation of β2-ARs, but not β1-ARs, promotes degradation of collagen, autophagy, ERK activation and cell proliferation through EGFR transactivation.65,66 In endothelial cells, β2-AR stimulation activates eNOS and vasodilation. Finally, β1-AR and other β-ARs are also emerging as relevant modulators of leukocyte trafficking to the injured heart, a key process for cardiac remodeling and repair after heart injury.67 The integrated functional impact of β-ARs and β-blockers in the different cardiac cell types is a key avenue for future research.

MECHANISM OF ACTION OF β-BLOCKERSAffinity is the ability of a drug to bind the receptor, and efficacy is the ability to induce a response. Drugs are classified as agonists or antagonists depending on whether or not they have efficacy.

All β-blockers share a common mechanism, which is their affinity for binding to β-ARs but, in contrast to β-AR agonists, they are not efficacious in evoking physiological responses. β-blockers compete with agonists for the binding site at β-AR, and the consequence is the inhibition of agonist activity. For this reason, they have been classically considered as competitive antagonists and their effects can be overcome by increasing the concentration of the agonist.15

Despite this common mechanism, in clinical studies, β-blockers do not behave as a single class of drugs. For example, bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol and nebivolol have been proved to be helpful in HF treatment, bucindolol had no benefit, and xamoterol increased mortality.15 Therefore, a more rigorous analysis of the mechanism of action is needed to understand the clinical usefulness of this group.

There are some aspects that make the difference:

- •

Selective affinity for β-AR subtypes. β-AR subtypes are not interchangeable entities and β-blockers exhibit a different affinity for each β-AR subtype, resulting in a particular pharmacological profile.

The functional consequences of β1-AR blockade in the heart are bradycardia and improved diastolic coronary filling time, reduced oxygen requirements, and a reduction in renin; all these effects are beneficial in HF and myocardial ischemia.68 However, the consequences of the blockade of β2 or β3-ARs are not positive since it avoids the bronchodilatation mediated by the β2 subtype, as well as the cardioprotective and vasodilatory mechanisms triggered by both subtypes. In fact, in vessels, they are present in vascular smooth muscle cells as well as endothelium, where they couple to the eNOS/NO-cGMP/PKG pathway, promoting vasodilation.69

The first group of the clinically available β-blockers exhibited higher affinity for the β1 and β2 subtypes than for the β3 subtype (Table 1), so at clinical doses, their therapeutic activity would be mainly related to β1- and β2-AR blockade (Table 2).

The “cardioselective” β-blockers have a higher affinity for the β1 subtype than for the β2 and β3 subtypes. When used at low doses, they inhibit cardiac β1-ARs but not β2–AR-mediated vasodilatation or bronchodilatation. However, β1-AR selectivity is relative (Table 1) and is lost with higher doses, and therefore the use of β1-selective blockers should be considered with caution in patients with airway diseases.

Of note, among the β-blockers that have been approved for the treatment of HF, bisoprolol and nebivolol are the most β1 selective, metoprolol exhibits moderate β1 selectivity, and carvedilol has slight β2-selectivity (Table 1). Therefore it is not possible to determine whether β1 selectivity is essential for maximal beneficial outcomes in HF.

- •

Inverse agonism. Traditional theory about drug-receptor interaction is based on a quiescent population of receptors that only act when they bind a ligand that possesses efficacy (agonist). However, we know that β-ARs, in the absence of agonists, can spontaneously adopt active conformations capable of regulating signaling systems70 and coupling to different transducing mechanisms.3 Therefore, the simplistic interpretation that β-blockers are drugs without efficacy to activate the receptor must be revised.

The evidence of this “constitutive activity” of β-ARs in the absence of agonists led to the discovery of drugs that could reduce it. Since their effects were opposite to those of agonists, these drugs were considered as “inverse agonists”,71 ie, rather than just occupying the binding site and thus blocking the actions of agonists, they stabilize the conformations of the receptor that are not coupled to G proteins, and prevent the constitutively activated signaling pathways. Although this idea was originally met with skepticism, it is now accepted that all receptors can signal in the absence of agonists and most β-blockers previously characterized as antagonists are now recognized as inverse agonists.16,21,23 What is the relevance of this observation? In a system with measurable constitutive activity, an inverse agonist will reduce receptor response whereas an antagonist does not, but both prevent the agonist activity.

Moreover, constitutive receptor activity results in activation of desensitization mechanisms that cause downregulation of receptors.70 Treatment with an inverse agonist stops this receptor downregulation, resulting in increased receptor expression and enhanced responsiveness to agonist stimulation.71 Sustained exposure of human β2-AR to inverse agonists resulted in (approximately) a doubling in membrane levels of the receptor, whereas equivalent treatment with an antagonist was unable to produce this effect.72

Studies in humans and animal models show upregulation of β1 and β2-ARs in the heart or β2-ARs in lymphocytes with chronic propranolol treatment, which is the reason for the observed β-AR supersensitivity after abrupt propranolol withdrawal.15 Moreover, β1-selective blockers such as atenolol, metoprolol and bisoprolol increase β1 but not β2-AR density.15 Because a general feature of HF patients is a decrease in cardiac β1-AR density,52,73 upregulation would be helpful in restoring maximal contractile responses. However, carvedilol did not upregulate cardiac β-ARs in HF patients, but was as effective as metoprolol and bisoprolol in improving cardiac performance.15 Therefore, it is under discussion whether upregulation of β-AR by β-blockers could be a beneficial property.

The data on the inverse agonist activity of β-blockers are summarized in Table 1.

- •

Partial agonism. Traditionally, some β-blockers have been considered to have intrinsic sympathomimetic activity. This activity appears if the drug has antagonist activity at the β1-AR subtype, but behaves as an agonist at another/others, or if the drug has the ability to promote a partial response of 1, 2 or all 3 subtypes (partial agonist). The consequence of partial activation of β-ARs is blockade of the stimulatory activity of high-efficacy agonists, such as catecholamines, but the stimulation of a low level of β-AR response in the absence of an agonist. This combined action could be beneficial since it manifests itself only when the sympathetic system is activated.74 However, β-blockers with partial agonist activity at β1-ARs appear to be less advantageous in the treatment of HF.28 On the other hand, an antagonist activity at β1-AR together with an agonist activity at β2- or β3-ARs produces vasodilatation and a cardioprotective effect that could represent an additional benefit.75

Older studies with β-blockers that detect intrinsic sympathomimetic activity do not differentiate between these mechanisms or the subtype involved. More recently, partial agonist activity on each β-AR subtype has been extensively studied at the cellular and tissue levels.17,74 Studies with human β-AR subtypes show differences depending on the β-blockers and the subtype studied: oxprenolol, carazolol, pindolol and nadolol have very evident partial agonist effects on β1 and β3-AR but no significant intrinsic activity on β2-ARs.17 Celiprolol has been described as an antagonist of the β1-subtype but as a partial agonist on β2 and β3-ARs.76

Table 1 summarizes some of the data available and shows conflicting results in some cases. Nebivolol does not promote cAMP accumulation in cells expressing the human β-AR subtypes17,18,28 and does not relax the rat urinary bladder, a prototypical β3–AR-mediated response,18 so it does not behave as a partial or total agonist in these conditions. However, nebivolol, through β3-AR activation, induces NO-mediated vasodilatation77–79 with a negative inotropic effect,80 and protects against myocardial infarction injury.81 Moreover, it reduces pulmonary vascular resistance and improves right ventricular performance in a porcine model of chronic pulmonary hypertension.82 These controversial results could be reconciled if we suppose that, depending on the cell type where the β3-AR is expressed, different signaling pathways were activated. This hypothesis links to the following section in which we address the concept of “biased agonism”.

- •

Biased agonism. A single β-AR can couple not only to 1 but to different G proteins, leading to complex signaling profiles including cAMP accumulation and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation.2 Additionally, for the β1 and β2 subtypes, G-protein-independent signaling has also been reported primarily through β-arrestins, which are responsible for desensitization/endocytosis machinery and noncanonical signaling via intracellular pathways such as the ERK1/2 mediated pathway.2,28

Ligands have been identified that bind β-ARs and activate distinct and specific subsets of these signaling pathways. This phenomenon has been referred to as “ligand-directed stimulus trafficking”, “functional selectivity”, and “biased agonism”.70,83 Particularly striking are studies reporting that some β-blockers can have opposite efficacies toward 2 different signaling pathways, suggesting that efficacy is a more complex parameter than was originally thought. In fact, multiple efficacy combinations are theoretically possible. Compounds could be agonist for the 2 pathways, inverse agonist for the 2 pathways, or have opposite efficacies on each of the pathways. For example, propranolol, which acts as an inverse agonist on the β2-AR toward Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway, was shown to be partial a agonist when tested on ERK activity.24

More interestingly, among an extensive group of β-blockers, only carvedilol22 and nebivolol32 induced β2-AR internalization and G protein-independent but β-arrestin-dependent activation of ERK1/2. Similar results have been described for carvedilol, alprenolol20 and nebivolol32 on β1-AR- β-arrestin-mediated EGFR transactivation. Given that β–arrestin-mediated β1-AR transactivation of EGFR may confer cardioprotection,49 β-blockers activating this pathway might possess superior efficacy in treating cardiovascular disorders.20 Additionally, carvedilol selectively promotes the recruitment and activation of Gαi to the β1-AR subtype triggering β-arrestin-mediated signaling.29

However, caution is advised because the cell or the physiological state may result in different results and interpretations of the signaling systems. Thus, other investigators84 failed to find evidence of β-arrestin recruitment by these β-blockers acting on β2-ARs (Table 1).

- •

Additional mechanisms. Individual properties of certain β-blockers are independent of their β-blocking properties but contribute to their therapeutic efficacy. They are summarized in Table 1 and include:

K+-channel blockade, as exerted by sotalol. This characteristic confers sotalol an additional antiarrhythmic activity characterized by slowing repolarization and prolonged action potential in cardiac tissues.27

α1-AR antagonist activity exerted by carvedilol30 and labetalol.31 This additional α1-adrenergic-blocking action leads to vasodilatation with a reduction in peripheral vascular resistance that acts to maintain higher levels of cardiac output. In contrast, nonvasodilating β-blockers tend to raise peripheral vascular resistance and reduce cardiac output and left ventricular function.

NO-releasing activity, which involves an additional vasodilator effect. This property was exhibited by nebivolol and could be mediated by a partial agonist activity mainly on β3-AR, although other not well determined mechanisms cannot be excluded.85 The increased NO release accompanied by decreased oxidative stress leads to an increase in NO bioavailability19 that participates in the antihypertensive activity of nebivolol. In the same way, carvedilol significantly increases plasma NO levels by stimulation of NOS86 and improves NO availability derived from its antioxidant properties. However, these actions do not appear to be mediated by a partial agonist activity on β3-AR.85

CONCLUSIONSSince their invention more than 50 years ago, β-blockers are still one of the most useful groups of drugs in clinical practice. They continue to be used for their original purpose to treat ischemic heart disease but, paradoxically, they are also effective in congestive HF. In addition, β-blockers are also used as antihypertensive drugs and in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias, esophageal variceal bleeding, and pulmonary hypertension. Furthermore, β-blockers have additional applications such as management of glaucoma, tremor, migraine, anxiety, and hyperthyroidism. The more that is known about their specific intracellular mechanisms of action, the greater the number of therapeutic applications. Emerging avenues of research should focus on the detailed study of unexplored, cell type-specific mechanism of β-blockers by considering them as individual molecules rather than as a homogeneous group of drugs. Half a century later, β-blockers will keep surprising the research community with new therapeutic applications undreamed by James Black.

FUNDINGF. Mayor is supported by Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (MINECO) of Spain (grant SAF2017-84125-R), CIBERCV-Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (grant CB16/11/00278, co-funded with European FEDER contribution), and Programa de Actividades en Biomedicina de la Comunidad de Madrid-B2017/BMD-3671-INFLAMUNE. E. Oliver is recipient of funds from Programa de Atracción de Talento (2017-T1/BMD-5185) of Comunidad de Madrid. The Spanish Center for Cardiovascular Research (CNIC) is supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades and the Pro CNIC Foundation and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (SEV-2015-0505). We also acknowledge institutional support to the Centro de Biología Molecular ‘Severo Ochoa’ from Fundación Ramón Areces.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

![Intracellular pathway mediated by β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs). 1: Main pathway: catecholamines bind to β-adrenoceptors inducing coupling to the heterotrimeric Gs protein; 2: Dissociation of the Gαs-GTP subunit and activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC); 3: Synthesis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP); 4: protein kinase A (PKA) activation; 5: Coordinated phosphorylation of various targets by PKA, including the plasma membrane L-type calcium channel (LTCC) or the RyR2 calcium channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, results in increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentration available for contraction of cardiac muscle. 6: Continuous stimulation (as described in chronic heart failure) of β1-AR induces apoptosis via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) leading to apoptosis and heart damage. 7: Continued stimulation of β2 (increased when using selective β1-blockers) induces coupling to Gi protein; 8: AC is inhibited by the Gα-GTP subunit of Gi; 9: The Gβγ subunit of Gi induces both the inhibition of apoptosis (via stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases [MAPK] and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K]-protein kinsase B [AKT] pathway) and of Gs-mediated deleterious effects (10), leading to cardioprotection. 11: In heart failure, stimulation of the β -adrenoceptor might lead to cardioprotection and a reduction in cardiac remodeling via nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activation. Adapted with permission from Watson et al.37. Intracellular pathway mediated by β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs). 1: Main pathway: catecholamines bind to β-adrenoceptors inducing coupling to the heterotrimeric Gs protein; 2: Dissociation of the Gαs-GTP subunit and activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC); 3: Synthesis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP); 4: protein kinase A (PKA) activation; 5: Coordinated phosphorylation of various targets by PKA, including the plasma membrane L-type calcium channel (LTCC) or the RyR2 calcium channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, results in increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentration available for contraction of cardiac muscle. 6: Continuous stimulation (as described in chronic heart failure) of β1-AR induces apoptosis via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) leading to apoptosis and heart damage. 7: Continued stimulation of β2 (increased when using selective β1-blockers) induces coupling to Gi protein; 8: AC is inhibited by the Gα-GTP subunit of Gi; 9: The Gβγ subunit of Gi induces both the inhibition of apoptosis (via stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases [MAPK] and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K]-protein kinsase B [AKT] pathway) and of Gs-mediated deleterious effects (10), leading to cardioprotection. 11: In heart failure, stimulation of the β -adrenoceptor might lead to cardioprotection and a reduction in cardiac remodeling via nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activation. Adapted with permission from Watson et al.37.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/18855857/0000007200000010/v1_201909250817/S1885585719301100/v1_201909250817/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=eyJpdiI6IlNUNHNWVjloMU01cExwaTlLa1dlRWc9PSIsInZhbHVlIjoiSUU4NFFTT0R5Q0gzWkpZNnBNV0Q3UWVtQlg0NEZqRXhrOVhHQUxhNjJBST0iLCJtYWMiOiI0ZGY0MGYzYzdjYzE2YzIxZTM0NzY0Nzg5ZDk2OTVhNGFjYmM1NDQ5YWNlNmE1NGJjNGVjZjEyYWVmM2M3ODI4IiwidGFnIjoiIn0=)