Keywords

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 5 to 8 million individuals with chest pain or other symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia are seen each year in emergency departments (ED) in the United States (1,2), which corresponds to 5 to 10% of all visits (3,4). Most of these patients are hospitalized for evaluation of possible acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This generates an estimated cost of 3 - 6 thousand dollars per patient(5,6). From this evaluation process, about 1,2 million patients receive the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and just about the same number have unstable angina. Therefore, about one-half to two-thirds of these patients with chest pain do not have a cardiac cause for his or her symptoms (2,3). Thus, the emergency physician is faced with the difficult challenge of identifying those with ACS – a life-threatening disease – to treat them properly, and to discharge the others to suitable outpatient investigation and management.

To establish the correct diagnosis and the appropriate treatment for patients with chest pain is one of the most important problems facing not only physicians and hospitals but also the payers – the government, the health-insurance companies or the patient. In attempting to identify those with ACS in the ED, physicians traditionally admit many individuals with non-cardiac chest pain to the coronary care unit or other hospital beds. This approach is responsible for the expenditure of some 5 to 10 billion dollars in cost for unnecessary hospital admissions (2,7,8). However, even with this exaggerated effort to identify cases of ACS, an average of 2 - 3% of patients with chest pain who actually have AMI are unintentionally released from the EDs in the United States, and this rate may go up to 11% in some centers (8-10) . This amounts to some 40,000 individuals each year. In countries where emergency physicians have less expertise in dealing with chest pain patients or are less aggressive in admitting them to the hospital this rate could reach 20% (11).

At the same time physicians have been pressured by health insurance companies and hospital managers to avoid admitting patients with an unclear diagnosis (12). Retrospective denial of payment by insurers for hospitalized patients who end up not having ACS makes the admission of low risk patients problematic. The release of patients with AMI represents a significant medico-legal risk for emergency physicians, with 20% of malpractice dollar settlements each year in the United States being associated with the misdiagnosis of AMI (13, 14) .

For all the previously mentioned reasons, physicians are faced with the problem of admitting most patients coming to the ED with chest pain, or releasing those that have a very low likelihood of a life-threatening disease, yet they may in fact have ACS with a resulting complication. Thus, most emergency physicians in the United States admit virtually all patients who have any possibility of ACS due to knowledge of the following information. First, some 15 to 30% of such patients actually have ACS (15,16). Second, just about one-half of patients with AMI have the classic change of ST-segment elevation on the admission ECG (17,18). Third, less than 50% of patients having AMI without ST-segment elevation have an abnormal admission creatine kinase-MB level (19-21). Therefore, the evolution of Chest Pain Units has been recognized as a reasonable and viable approach to deal with these patients in a cost-effective way (12,22).

CHEST PAIN UNITS

Chest Pain Units or Centers can be defined as a new area of emergency medical care devoted to improve management of patients with acute chest pain or any other symptom suggestive of ACS. The main objectives of these units are to provide 1) easy and friendly admission for the patient presenting to the ED, 2) priority and rapid access to the medical staff on the ED, and 3) organized and efficient strategy of medical care within the ED, including diagnosis and treatment, aimed to dispense the best possible medical care at the lowest possible cost.

Chest Pain Units can be located in or adjacent to the ED, in a true physical area or just as a working process within the emergency center. What is essential is that a group of trained and qualified personnel act in synchrony when receiving a patient with chest pain to achieve the previously mentioned objectives: rapid and efficient evaluation, early identification of ACS, high-quality care, and cost-effectiveness (2,3,23,24).

One of the keys for the success of the Chest Pain Units is the use of systematic diagnostic algorithms and specific management protocols (3,24). These models are subsequently discussed in this paper. The use of Chest Pain Units has resulted in improved care of patients with and without ACS as depicted in Table 1. Pre-hospital delay (procrastination of patients with ACS in coming to the ED) is a worldwide problem and responsible for about 50% of deaths in AMI (25,26). Many studies have demonstrated that the mean time-interval between symptom onset and hospital arrival in patients with AMI is 2 to 3 hours (2,27). This is one of the reasons for ineligibility for thrombolytic therapy in many patients with AMI (28). Chest Pain Units can be an instrument for patients’ education, particularly for those needing risk factor modification or symptom recognition (2,3).

In-hospital delay, the time interval between hospital arrival and diagnosis with initiation of specific therapy, is another problem that affects most of the hospitals around the world, even in developed countries. This time frame is about one hour (2,27). Chest Pain Units perform an important and unique role in reducing this delay through its action to prioritize high risk individuals and to use protocols to evaluate and treat patients (2,3,12,24), as recommended by the National Heart Attack Alert Program (29).

Inappropriate hospital release of patients with AMI and unstable angina is a serious problem in emergency medicine that has been persistent over time (9,10,30,31). As previously mentioned, diagnostic error in these cases has ranged from zero to more than 10% in renowned medical institutions (10). Through the training of its personnel and the use of careful and systematic diagnostic strategies, Chest Pain Units can decrease inappropriate AMI release to less than 1%. Cost-containment initiatives make the Chest Pain Centers more attractive as low-risk patients can have thorough evaluations in an efficient fashion (10).

Excessive and unnecessary hospitalizations in high-complexity, high-cost units, such as coronary care units, are a frequent problem in medical practice, especially when physicians are in need of a bed for their patients with known AMI. Chest Pain Units act to buffer the coronary care units by evaluating patients with an unclear diagnosis, therefore reducing the rate of low-risk admissions and, consequently, increasing the availability of beds for those who really need them (24,32).

The high costs of contemporary medicine have proved to be an important economic burden for society. Money used unwisely for the management of low-risk chest pain patients could be used to optimize cost-efficiency. Chest Pain Units have been demonstrated to reduce these costs, mainly through reduction of hospital stay duration and the amount of diagnostic tests ordered using strict protocol guidelines (5,7,26,33-36). As they also improve medical care quality, through a protocol - driven approach to diagnosis and treatment, Chest Pain Units promote an unquestionable salutary shift in the cost-benefit relationship.

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIES FOR CHEST PAIN PATIENTS

Chest pain is a symptom associated with multiple pathologic entities, some benign (37). However, emergency physicians are usually concerned primarily with those that are life-threatening, namely ACS, pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection.

The history is an extremely valuable tool in the differential diagnosis of chest pain (37-41). The association of chest pain characteristics and admission ECG changes, with or without the information of patient’s age and past history, has enabled investigators to create probabilistic algorithms or clinical prediction rules to estimate the chance of ACS or myocardial infarction in these patients (16,21,37,42,43). The diagnostic accuracy of these tools has been confirmed in several studies (44-47) and recommended in one guideline (48).

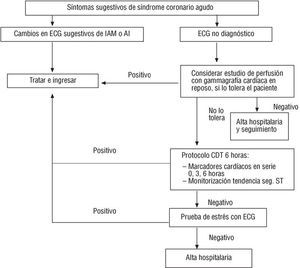

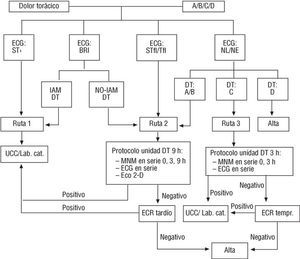

Determination of pre-test probability of ACS is important in establishing diagnostic strategies that are most cost-effective. Thus, patients with a high probability should be thoroughly investigated whereas patients with low probability of ACS may need less extensive and costly investigation in the emergency setting. Several strategies have been proposed and used in different centers (8,21,42,49-51) but they all have in common the need for a diligent and careful determination of the pre-test probability of disease and the proper allocation of resources. Figures 1 and 2 depict the diagnostic strategies used in the University of Cincinnati Medical Center (8,49) and Pro-Cardiaco Hospital (21,32), respectively.

Figure 1

Figure 2

DEVELOPING A PROTOCOL FOR THE CHEST PAIN UNIT

Since the early 1960’s coronary care units have been the ideal setting for managing patients with a clear-cut diagnosis of AMI. The excellent results observed in these units, particularly with early recognition and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac arrest, led physicians to begin admitting patients with suspected ACS (52,53). The result of this more liberal approach was more than one-half of admitted patients did not have a final diagnosis of ACS (53). Consequently, high-cost hospital beds were filled by emergency physicians with low-risk patients, resulting in saturation or overflow of the coronary care units, with sub optimal use of medical resources, and high costs associated with this evaluation.

Chest Pain Units are a structured approach for assessing patients that come to the ED with chest pain and possible ACS (22,23) . Dedicated physicians and nurses can make a quick and accurate assessment of the patient’s risk of ACS with a careful history and the readily available ECG (32,37,38,54). Serum markers such as myoglobin, CK-MB and troponins I and T also help risk stratify these patients (5,19,55) . Patients with a diagnosis of ACS confirmed in the ED at this point should be admitted to the hospital, have their therapy initiated in the emergency setting, and then evaluated for possible percutaneous coronary intervention. The duration of myocardial necrosis markers screening should be not less than 3 hours and generally between 6 and 9 hours after admission to the Chest Pain Centers. Ideally, three markers should be obtained until at least 12 hours after pain onset (19-21,49,53,55).

Remaining patients with a negative series of myocardial necrosis markers still require an evaluation for acute cardiac ischemia. ST-segment trend monitoring, two-dimensional echocardiography and rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy have been systematically used with or without cardiac necrosis markers determinations in acute chest pain patients presenting to the ED with possible ACS (42,49,50). Sensitivity of tetrofosmin or sestamibi SPECT for detecting AMI has ranged from 90 to 100%, with a negative predictive value of 99%(42,56-59) , whereas the rest echocardiogram is between 47 - 93% and 86 - 99 %, respectively (32,49,60-62). Diagnostic accuracy of ST- segment trend monitoring is still under investigation (63,64).

Graded exercise testing, with or without myocardial radionuclide scintigraphy or stress echocardiography, can be performed to further risk-stratify these patients, as recommended by several groups (32,33,49,65). Although these tests are important tools to assist in the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia and, therefore, unstable angina, they also contribute to assess prognosis in acute chest pain patients. A negative exercise test is associated with minimal (< 2%) chance of death or acute myocardial infarction in the following year(5,42,56,57,62,66,67). Thus, provocative testing becomes extremely important in completing the Chest Pain Unit evaluation in these patients.

Therefore, the Chest Pain Units provide a thorough evaluation for patients with chest pain presenting to the ED. These units must provide assessment for myocardial necrosis, rest ischemia, and exercise-induced ischemia. Patients with a negative evaluation that encompasses these three objectives have a very low risk for complications after discharge from the Chest Pain Unit and can be safely sent for early follow-up with their cardiologist or internist.

CONCLUSION

The introduction of Chest Pain Units in the management of patients that come to the ED with chest pain has permitted the diagnosis of ACS to be made outside the coronary care unit in a more rapid and accurate way, thus optimizing assessment and treatment of these patients. Conversely, it has allowed individuals with chest pain of other causes to be investigated in a less complex and inexpensive environment, releasing them safely from the hospital. The final consequence of the proper use of Chest Pain Units has been a significant reduction in diagnostic errors, decreased hospital admissions with occupancy of coronary care unit beds by higher risk patients, and more appropriate diagnostic testing. Finally, Chest Pain Units provide more cost - effective care. Therefore, Chest Pain Units have come to serve as a contemporary medical practice that provides high quality, efficient care at a reduced cost.

Address for correspondence:Roberto Bassan, MD Hospital Pro-Cardiaco R. General Polidoro, 192Rio de Janeiro, 22280-000, Brazil Ph: (55) (21) 537-4242 Fax: (55) (21) 286-5485

e-mail: procep@uninet.com.br