Patients who are vulnerable to hemodynamic or electrical disorders (VP) are often excluded from clinical trials and data on the optimal access-site or antithrombotic treatment are limited. We assessed outcomes of transradial vs transfemoral access and bivalirudin vs unfractionated heparin (UFH) in VP with acute coronary syndrome undergoing invasive management.

MethodsThe MATRIX trial randomized 8404 patients to radial or femoral access and 7213 patients to bivalirudin or UFH. Among them, 934 (11.1%) were deemed VP due to advanced Killip class (n = 808), cardiac arrest (n = 168), or both (n = 42). The 30-day coprimary outcomes were major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACE: death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) and net adverse clinical events (NACE: MACE or major bleeding).

ResultsMACE and NACE were similarly reduced with radial vs femoral access in VP and non-VP. Transradial access was also associated with consistent relative benefits in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality or Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 3 or 5 bleeding with greater absolute benefits in VP. The effects of bivalirudin vs UFH on MACE and NACE were consistent in VP and non-VP. Bivalirudin was associated with lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in VP but not in non-VP, with borderline interaction testing. Bivalirudin reduced bleeding in both VP and non-VP with a larger absolute benefit in VP.

ConclusionsIn acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing invasive management, the effects of randomized treatments were consistent in VP and non-VP, but absolute risk reduction with radial access and bivalirudin were greater in VP, with a 5- to 10-fold lower number needed to treat for benefits.

Trial registry number: NCT01433627.

Keywords

Transradial access intervention (TRA) has been widely adopted in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and is recommended by guidelines over transfemoral access (TFA) in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients.1,2 Compared with TFA, TRA has numerous advantages, including lower rates of major bleeding, shorter bed rest time, and earlier hospital discharge, all of which are of particular importance in ACS patients undergoing invasive management. In contrast, concerns have been raised about the use of TRA in vulnerable patients (VP) such as those with concomitant hemodynamic (advanced Killip class) or electrical (out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [OHCA] survivors) disorders in whom TFA might still remain preferable to deliver timely treatment. Prior studies, including the pivotal RIVAL trial, have excluded cardiogenic shock patients, and data on OHCA undergoing TRA are limited.3

Heart failure (HF) is associated with elevated thrombin levels leading to faster formation of compact and resistant fibrin clots. Recent observational data suggest that HF patients undergoing PCI might benefit from a direct, such as bivalirudin, compared with an indirect, such as unfractionated heparin (UFH), thrombin inhibitor due to lower mortality and bleeding risks.4,5

We sought to investigate the comparative safety and effectiveness of TRA vs TFA and bivalirudin vs UFH in VP with ACS undergoing invasive management.

METHODSStudy design and patientsDesign and primary findings of the Minimizing Adverse Haemorrhagic Events by Transradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of Angiox (MATRIX) trial have been previously reported.6–8 Briefly, MATRIX (NCT01433627) was a program of 3 independent randomized controlled trials in an all-comers population with ACS. The first trial, MATRIX-Access Site, compared TRA with TFA in 8404 ACS patients. The second trial, MATRIX-Antithrombin (n=7213), was a randomized comparison of 2 antithrombotic strategies: bivalirudin with use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) restricted to angiographic complications (no-reflow or giant thrombus) compared with UFH with use of GPI left to the investigator's discretion. The third trial, MATRIX-Treatment-Duration, was a randomized comparison within patients assigned to bivalirudin, comparing prolonged (after PCI) with short-term (during PCI only) bivalirudin administration. VPs were those presenting with acute HF (Killip class II to IV)9–11 or OHCA at the time of randomization. The trial was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Study protocol and randomizationPatients were randomized to receive treatments in a 1:1 ratio, with a random block size stratified by type of ACS, intended or ongoing use of P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel vs ticagrelor or prasugrel), and study site. All interventions were administered in an open-label fashion. Access site management during and after the diagnosis or therapeutic procedure was left to the discretion of the treating physician, and closure devices were allowed as per local practice. Bivalirudin was administered according to the product labeling, with a 0.75mg/kg bolus, followed immediately by a 1.75mg/kg/h infusion until completion of the PCI. In those assigned to bivalirudin prolongation, the choice between 2 regimens (full dose for up to 4hours or a reduced dose of 0.25mg/kg/h for at least 6hours) was made at the discretion of the treating physicians. UFH was administered at a dose of 70 to 100 units or 50 to 70 units/kg in patients not receiving or receiving GPI, respectively. Subsequent UFH dose adjustment on the basis of the activated clotting time was left to the discretion of the treating physicians. A GPI could be administered before PCI in all patients in the UFH group on the basis of the treating physician's judgment, but the drug was to be administered in the bivalirudin group only in patients who had periprocedural ischemic complications after PCI. The use of other medications was allowed according to professional guidelines.

Follow-up and study outcomesClinical follow-up was performed at 30 days. The 2 coprimary 30-day composite outcomes of the MATRIX-Access and Antithrombin trials were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the composite of all-cause mortality, MI, or stroke; and net adverse clinical events (NACE), defined as the composite of MACE or noncoronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)-related major bleeding (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] type 3 or 5). The primary outcome for MATRIX-Treatment-Duration was a composite of urgent target vessel revascularization (TVR), definite stent thrombosis, or NACE. Secondary outcomes included each component of the composite outcomes, cardiovascular mortality, and stent thrombosis (defined as the definite or probable occurrence of a stent-related thrombotic event according to the Academic Research Consortium classification). Bleeding was also assessed and adjudicated on the basis of the Thrombosis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Arteries (GUSTO) scales. All outcomes were prespecified. An independent clinical events committee blinded to treatment allocation adjudicated all suspected events.

Statistical analysisThe MATRIX-Access and Antithrombin trials were designed as superiority studies on 2 coprimary outcomes at 30 days, expecting a rate reduction of 30%, corresponding to a rate ratio of 0.70. All analyses were performed per intention-to-treat principle, including all patients in the analysis based on the allocated treatment. Events up to 30 days postrandomization were considered. We analyzed primary and secondary outcomes separately for VP and non-VP patients as time to first event using the Mantel-Cox method, accompanied by log-rank tests to calculate corresponding 2-sided P values. We did not perform any adjustments for multiple comparisons but set the alpha error at 2.5% to correct for the 2 coprimary outcomes. We analyzed secondary outcomes with a 2-sided α set at 5% to allow conventional interpretation of results. Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan–Meier estimates. Absolute risk differences and number needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) were also calculated. We performed secondary analyses in the VP group to separately assess clinical outcomes in the HF and OHCA subgroups. We also performed stratified analyses according to prespecified subgroups (the center's annual volume of PCI, the center's proportion of radial PCI, age, sex, type of ACS, body mass index, intended start or continuation of prasugrel or ticagrelor, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, history of peripheral vascular disease, previous heparin, and randomization to access site/antithrombin type) and estimated possible effect modifications using interaction terms or tests for trend across ordered groups separately for the VP and non-VP study populations. We also performed sensitivity analyses by using Cox regression analysis (unadjusted and adjusted) for coprimary endpoints and all-cause mortality and competing risk analysis (for death) for individual components of coprimary endpoints (MI, stroke and BARC 3 or 5). All analyses were performed using the statistical package Stata 15.1 and R 3.4.4.

RESULTSThe MATRIX-Access trial enrolled 8404 patients with ACS from 78 centers in Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden between October 2011 and November 2014. Among them, 934 (11.1%) were deemed VP—due to advanced Killip class in 808 patients (Killip class II = 569, III = 167, IV = 72) and/or OHCA in 168 with a total of 42 patients (Killip class II = 23, III = 6, IV = 13) exhibiting both conditions—, of whom 462 (5.5%) were allocated to radial and 472 (5.6%) to femoral access. Among the 7213 patients enrolled in the MATRIX-Antithrombin, 819 (11.4%) fulfilled the VP criteria—due to advanced Killip class in 698 patients and/or OHCA in 163 with a total of 42 patients exhibiting both conditions—, of whom 397 (5.5%) were allocated to bivalirudin and 422 (5.9%) to UFH.

Baseline and procedural characteristics were largely imbalanced between VP and non-VP (table 1 and table 2), while VP and non-VP subgroups allocated to radial vs femoral access or bivalirudin vs UFH were generally well matched across demographics, medical history, clinical presentation, and procedural characteristics ().

Baseline characteristics in patients with or without hemodynamic or electrical vulnerability

| VP (HF and/or OHCA) | HF (KC > 1) | OHCA | Non-VP | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 934 | 808 | 168 | 7470 | |

| Age, y | 69.5 (11.6) | 70.4 (11.2) | 64.0 (11.9) | 65.3 (11.8) | <.0001 |

| ≥ 75 y | 367 (39.3) | 340 (42.1) | 36 (21.4) | 1815 (24.3) | < .0001 |

| Men | 637 (68.2) | 546 (67.6) | 125 (74.4) | 5535 (74.1) | .0001 |

| BMI, kg/my | 27.1 (4.6) | 27.2 (4.6) | 26.9 (4.5) | 27.1 (4.1) | .5861 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 300 (32.1) | 281 (34.8) | 28 (16.7) | 1603 (21.5) | < .0001 |

| Insulin-dependent | 94 (10.1) | 88 (10.9) | 9 (5.4) | 372 (5.0) | < .0001 |

| Current smoker | 290 (31.0) | 239 (29.6) | 69 (41.1) | 2597 (34.8) | .0241 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 390 (41.8) | 340 (42.1) | 69 (41.1) | 3301 (44.2) | .1576 |

| Hypertension | 650 (69.6) | 587 (72.6) | 83 (49.4) | 4661 (62.4) | < .0001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 190 (20.3) | 177 (21.9) | 22 (13.1) | 1013 (13.6) | < .0001 |

| Previous PCI | 166 (17.8) | 154 (19.1) | 22 (13.1) | 1029 (13.8) | .0010 |

| Previous CABG | 44 (4.7) | 41 (5.1) | 3 (1.8) | 213 (2.9) | .0019 |

| Previous TIA or stroke | 67 (7.2) | 62 (7.7) | 9 (5.4) | 358 (4.8) | .0017 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 134 (14.3) | 125 (15.5) | 16 (9.5) | 579 (7.8) | < .0001 |

| Renal failure | 41 (4.4) | 40 (5.0) | 2 (1.2) | 64 (0.9) | < .0001 |

| Dialysis | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.1) | .2206 |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 517 (55.4) | 418 (51.7) | 139 (82.7) | 3493 (46.8) | < .0001 |

| NSTE-ACS | 417 (44.6) | 390 (48.3) | 29 (17.3) | 3977 (53.2) | < .0001 |

| NSTE-ACS, troponin positive | 384 (41.1) | 360 (44.6) | 26 (15.5) | 3502 (46.9) | .0009 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 44.4 (11.4) | 43.8 (11.7) | 45.9 (10.1) | 51.9 (9.1) | < .0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 131.5 (30.6) | 131.8 (31.3) | 123.6 (28.1) | 139.6 (24.7) | < .0001 |

| Heart rate | 82.2 (21.0) | 83.3 (21.2) | 77.4 (21.3) | 75.4 (15.9) | < .0001 |

| eGFR | 74.3 (27.1) | 73.1 ±27.2 | 78.9 (25.4) | 84.9 (25.0) | < .0001 |

| eGFR<60 mL/min | 305 (33.0) | 280 (35.1) | 41 (24.6) | 1110 (15.0) | < .0001 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; KC, Killip class; NSTE-ACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VP, hemodynamic/electrical vulnerable patients.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Procedural characteristics in patients with or without hemodynamic or electrical vulnerability

| VP (HF and/or OHCA) | HF (KC > 1) | OHCA | Non-VP | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 934 | 808 | 168 | 7470 | |

| Only radial access site | 428 (45.8) | 369 (45.7) | 80 (47.6) | 3592 (48.1) | .1921 |

| Only femoral access site | 455 (48.7) | 391 (48.4) | 82 (48.8) | 3642 (48.8) | .9817 |

| Both radial and femoral access site | 51 (5.5) | 48 (5.9) | 6 (3.6) | 229 (3.1) | .0001 |

| Other access site | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.1) | - |

| Crossover | 51 (5.5) | 48 (5.9) | 6 (3.6) | 232 (3.1) | .0002 |

| Coronary angiography completed | 934 (100.0) | 808 (100.0) | 168 (100.0) | 7461 (99.9) | - |

| Medications in the catheterization laboratory | |||||

| Aspirin | 52 (5.6) | 41 (5.1) | 14 (8.3) | 429 (5.7) | .8277 |

| Clopidogrel | 70 (7.5) | 63 (7.8) | 8 (4.8) | 453 (6.1) | .0880 |

| Prasugrel | 59 (6.3) | 41 (5.1) | 29 (17.3) | 567 (7.6) | .1623 |

| Ticagrelor | 92 (9.9) | 73 (9.0) | 24 (14.3) | 684 (9.2) | .4901 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 439 (47.0) | 381 (47.2) | 82 (48.8) | 3457 (46.3) | .6758 |

| GPI | 150 (16.1) | 128 (15.8) | 34 (20.2) | 945 (12.7) | .0035 |

| Planned GPI | 105 (11.2) | 88 (10.9) | 28 (16.7) | 678 (9.1) | .0318 |

| Bailout GPI | 45 (4.8) | 40 (5.0) | 6 (3.6) | 267 (3.6) | .0580 |

| Bivalirudin | 373 (39.9) | 314 (38.9) | 75 (44.6) | 3054 (40.9) | .5784 |

| Post-PCI bivalirudin | 181 (19.4) | 151 (18.7) | 40 (23.8) | 1544 (20.7) | .3573 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 81 (10.9) | 77 (12.2) | 14 (9.3) | 75 (1.3) | < .0001 |

| CABG after coronary angiography | 48 (5.1) | 47 (5.8) | 2 (1.2) | 262 (3.5) | .0128 |

| Completed PCI after coronary angiography | 741 (79.3) | 630 (78.0) | 151 (89.9) | 5983 (80.1) | .5852 |

| At least 1 planned staged procedure | 168 (18.0) | 136 (16.8) | 35 (20.8) | 1340 (17.9) | .9708 |

| Treated vessel(s) | |||||

| Left main coronary artery | 84 (11.3) | 81 (12.9) | 10 (6.6) | 185 (3.1) | < .0001 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 399 (53.8) | 342 (54.3) | 77 (51.0) | 2915 (48.7) | .0085 |

| Left circumflex artery | 201 (27.1) | 178 (28.3) | 34 (22.5) | 1599 (26.7) | .8167 |

| Right coronary artery | 217 (29.3) | 178 (28.3) | 53 (35.1) | 1998 (33.4) | .0247 |

| Bypass graft | 10 (1.3) | 10 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 45 (0.8) | .0886 |

| ≥ 2 vessels treated | 153 (20.6) | 143 (22.7) | 19 (12.6) | 733 (12.3) | < .0001 |

| Overall stent length, mm | 34.7 (22.0) | 35.3 (22.1) | 32.8 (22.2) | 31.3 (19.1) | < .0001 |

| Duration of procedure, min | 58.3 (28.5) | 59.3 (28.9) | 56.8 (29.3) | 54.2 (28.1) | .0002 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; GPI, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; HF, heart failure; KC, Killip class; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; VP, hemodynamic/electrical vulnerable patients.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

Rates of MACE and NACE were higher in VP than in non-VP, as were nearly all secondary outcomes ().

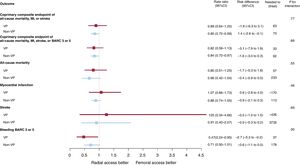

No significant interaction was noted between access site and VP criteria with respect to 30-day MACE and NACE coprimary endpoints (interaction P=.77 and 0.89, respectively; figure 1 and table 3; ). MACE and NACE were similarly reduced with radial compared with femoral in VP (MACE: 14.9% vs 16.5%; RR, 0.89; 95%CI, 0.64-1.25; P = .51; NACE: 15.8% vs 18.9%; RR, 0.82; 95%CI, 0.59-1.13; P = .22) or in non-VP (MACE: 8.1% vs 9.5%; RR, 0.85; 95%CI: 0.72-0.99; P = .039; NACE: 9.0% vs 10.7%; RR, 0.84; 95%CI: 0.72-0.97; P = .022) patients (). TRA provided consistent relative benefits over TFA in terms of individual endpoints (table 3; figure 2 and ), including all-cause mortality (interaction P = .55), cardiovascular mortality (interaction P = .46), and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (interaction P = .30). Absolute benefits in favor of TRA over TFA were at least four-fold greater in VP compared with non-VP (absolute risk difference of −1.7%, −1.5% and −2.7% in VP and −0.4%, −0.4% and −0.6% in non-VP for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding respectively; as shown on table 3, and on ).

Main outcomes of radial vs femoral access in VP and non-VP. Radial and femoral access were compared on the basis of hemodynamic/electric vulnerability, with rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), for the coprimary endpoints and their components (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, BARC 3 or 5). BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MI, myocardial infarction; VP, vulnerable patients.

Main clinical outcomes at 30 days of TRA vs TFA and bivalirudin vs UFH in patients with or without hemodynamic or electrical vulnerability

| VP | Non-VP | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial access | Femoral access | Risk difference (%) | NNT/NNH | Rate ratio (95%CI) | P | Radial access | Femoral access | Risk difference (%) | NNT/NNH | Rate ratio (95%CI) | P | P for interaction | |

| Number of patients | 462 | 472 | 3735 | 3735 | |||||||||

| Coprimary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, MI or stroke | 69 (14.9) | 78 (16.5) | −1.6 (−6.3 to 3.1) | 63 | 0.89 (0.64-1.25) | .51 | 300 (8.1) | 351 (9.5) | −1.4 (−2.6 to −0.1) | 73 | 0.85 (0.72-0.99) | .039 | .77 |

| Coprimary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, or BARC 3 or 5 | 73 (15.8) | 89 (18.9) | −3.1 (−7.9 to 1.8) | 33 | 0.82 (0.59-1.13) | .22 | 337 (9.0) | 397 (10.7) | −1.6 (−3.0 to −0.3) | 62 | 0.84 (0.72-0.97) | .022 | .89 |

| Composite of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, urgent TVR, definite stent thrombosis | 74 (16.0) | 89 (18.9) | −2.8 (−7.7 to 2.0) | 35 | 0.83 (0.60-1.14) | .25 | 345 (9.3) | 402 (10.9) | −1.5 (−2.9 to −0.2) | 66 | 0.85 (0.73-0.98) | .030 | .91 |

| All-cause mortality | 35 (7.6) | 44 (9.3) | −1.7 (−5.3 to 1.8) | 57 | 0.80 (0.51-1.25) | .32 | 31 (0.8) | 47 (1.3) | −0.4 (−0.9 to 0.0) | 233 | 0.66 (0.42-1.04) | .068 | .55 |

| Cardiovascular death | 34 (7.4) | 42 (8.9) | −1.5 (−5.0 to 2.0) | 65 | 0.81 (0.51-1.28) | .37 | 26 (0.7) | 41 (1.1) | −0.4 (−0.8 to 0.0) | 249 | 0.63 (0.39-1.03) | .065 | .46 |

| Myocardial infarction | 36 (7.8) | 34 (7.2) | 0.6 (−2.8 to 4.0) | −170 | 1.07 (0.66-1.73) | .78 | 263 (7.1) | 296 (7.9) | −0.9 (−2.1 to 0.3) | 113 | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | .15 | .46 |

| Stroke | 5 (1.1) | 4 (0.9) | 0.2 (−1.0 to 1.5) | −426 | 1.25 (0.34-4.66) | .74 | 11 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | −0.0 (−0.3 to 0.2) | 3735 | 0.91 (0.40-2.07) | .83 | .69 |

| BARC Type 3 or 5 | 12 (2.7) | 25 (5.5) | −2.7 (−5.2 to −0.2) | 37 | 0.47 (0.24-0.95) | .031 | 53 (1.4) | 74 (2.0) | −0.6 (−1.1 to 0.0) | 178 | 0.71 (0.50-1.01) | .059 | .30 |

| Composite of surgical access site repair or blood products transfusion | 8 (2.0) | 18 (4.0) | −2.1 (−4.2 to 0.0) | 48 | 0.44 (0.19-1.01) | .047 | 34 (0.9) | 55 (1.5) | −0.6 (−1.1 to −0.1) | 178 | 0.62 (0.40-0.94) | .025 | .48 |

| Bivalirudin | UFH | Bivalirudin | UFH | ||||||||||

| Number of patients | 397 | 422 | 3213 | 3181 | |||||||||

| Coprimary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, MI or stroke | 61 (15.4) | 76 (18.0) | −2.6 (−7.7 to 2.5) | 38 | 0.84 (0.59-1.19) | .33 | 313 (9.8) | 316 (10.0) | −0.2 (−1.7 to 1.3) | 520 | 0.98 (0.83-1.15) | .80 | .43 |

| Coprimary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, or BARC 3 or 5 | 63 (15.9) | 89 (21.1) | −5.2 (−10.5 to 0.1) | 19 | 0.73 (0.52-1.02) | .064 | 345 (10.8) | 361 (11.4) | −0.6 (−2.1 to 0.9) | 164 | 0.94 (0.81-1.10) | .45 | .17 |

| Composite of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, urgent TVR, definite stent thrombosis | 64 (16.1) | 89 (21.1) | −5.0 (−10.3 to 0.3) | 20 | 0.74 (0.53-1.04) | .079 | 351 (11.0) | 367 (11.6) | −0.6 (−2.2 to 0.9) | 163 | 0.94 (0.81-1.10) | .45 | .20 |

| All-cause mortality | 24 (6.0) | 48 (11.4) | −5.3 (−9.2 to −1.5) | 19 | 0.51 (0.31-0.84) | .0070 | 35 (1.1) | 35 (1.1) | −0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | 9125 | 0.99 (0.62-1.58) | .97 | .056 |

| Cardiovascular death | 23 (5.8) | 47 (11.1) | −5.3 (−9.1 to −1.6) | 19 | 0.50 (0.30-0.83) | .0063 | 30 (0.9) | 30 (1.0) | −0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | 10 646 | 0.99 (0.60-1.65) | .97 | .060 |

| Myocardial infarction | 39 (10.0) | 28 (6.9) | 3.2 (−0.6 to 7.0) | −31 | 1.46 (0.88-2.41) | .14 | 271 (8.5) | 277 (8.8) | −0.3 (−1.6 to 1.1) | 366 | 0.97 (0.81-1.15) | .71 | .13 |

| Stroke | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.6) | −0.7 (−2.1 to 0.7) | 150 | 0.50 (0.13-2.01) | .32 | 10 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | −0.0 (−0.3 to 0.3) | 31 939 | 0.99 (0.41-2.38) | .98 | .41 |

| BARC Type 3 or 5 | 8 (2.1) | 27 (6.7) | −4.4 (−7.1 to −1.7) | 23 | 0.30 (0.13-0.66) | .0015 | 47 (1.5) | 71 (2.3) | −0.8 (−1.4 to −0.1) | 130 | 0.65 (0.45-0.95) | .023 | .073 |

| Composite of surgical access site repair or blood products transfusion | 5 (1.6) | 18 (4.5) | −3.0 (−5.2 to −0.8) | 33 | 0.28 (0.10-0.75) | .0072 | 31 (1.0) | 50 (1.6) | −0.6 (−1.2 to −0.1) | 165 | 0.61 (0.39-0.96) | .031 | .15 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MI, myocardial infarction; NNT/NNH, number needed to treat/harm; TVR, target vessel revascularization; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VP, hemodynamic/electrical vulnerable patients.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as No. (%).

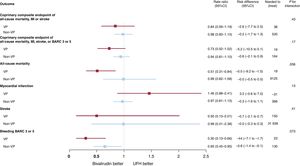

There was also no interaction between allocation to antithrombin treatment and VP criteria for MACE or NACE (interaction P=.43 and.17, respectively; see figure 2 and table 3; ). Bivalirudin was associated with a nominally significant reduction in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared with UFH in VP (all-cause mortality: RR, 0.51; 95%CI, 0.31-0.84; P = .007; cardiovascular mortality: RR, 0.50; 95%CI, 0.30-0.83; P = .006; with risk differences of −5.3% for both), but not in non-VP (all-cause mortality: RR, 0.99; 95%CI, 0.62-1.58; P = .97; cardiovascular mortality: RR, 0.99; 95%CI: 0.60-1.65; P = .97; with risk differences of 0% for both; see table 3; ). However, interaction testing for both endpoints did not reach statistical significance (interaction P = .056 and .060 respectively, ). Bivalirudin reduced BARC 3 or 5 bleeding rates in both VP (RR, 0.30; 95%CI, 0.13-0.66; P = .0015) and non-VP (RR 0.65; 95%CI, 0.45-0.95; P = .023) groups compared with UFH (interaction P = .073), with somewhat greater absolute benefit in the former (absolute risk difference −4.4%) compared with the latter group (absolute risk difference −0.8%; table 3; ).

Main outcomes of bivalirudin vs UFH in VP and non-VP. Bivalirudin and UFH were compared on the basis of hemodynamic/electric vulnerability, with rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), for the coprimary endpoints and their components (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, BARC 3 or 5). BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MI, myocardial infarction; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VP, vulnerable patients.

Overall findings were largely consistent when the VP group was stratified according to the presence, absence or severity of advanced Killip class or OHCA at presentation as well as according to prespecified subgroups (data not shown) or alternative statistical methods were applied ().

DISCUSSIONMATRIX is the largest and most contemporary randomized trial comparing TRA vs TFA and the only study nesting the access site comparison with a random selection of antithrombin types, including bivalirudin or UFH (± GPI) in ACS patients undergoing invasive management. In this study, 11.1% of patients presented with hemodynamic (advanced Killip class) or electrical instability (OHCA survivors) and were deemed VP according to the post hoc analysis.

Our main findings can be summarized as follows:

VP (9.6% with acute HF and 2.0% with OHCA, with 0.5% exhibiting both conditions) more frequently had cardiovascular risk factors, more frequently fulfilled procedural complexity criteria and experienced a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes compared with non-VP.

Radial access was associated with a consistent relative risk reduction of composite primary as well as key secondary endpoints, including mortality and severe bleeding events, in VP and non-VP groups compared with TFA. However, since the event rate was much higher in VP, these patients experienced a larger absolute risk reduction with TFA compared with non-VP group.

The comparative safety and effectiveness of bivalirudin vs UFH were consistent between VP and non-VP, with greater absolute bivalirudin-related benefits in the former compared with the latter group.

Access site selection in patients with hemodynamic or electrical vulnerabilityPatients with ACS presenting with hemodynamic or electrical vulnerability are frequent in daily practice and suffer from a higher risk of morbidity and mortality. European Society of Cardiology guidelines underline that high-risk ACS patients with acute HF, cardiogenic shock or OHCA are those who benefit the most from expediting all steps of the care pathway.1,2 Nevertheless, there is no specific recommendation concerning the preferable access site or antithrombotic treatment combination for angiography and/or PCI, if clinically indicated. This reflects the paucity of randomized data on this high-risk ACS patient population undergoing invasive management.

TRA is recommended over TFA in ACS patients across the board in the European guidelines but not in the ACC/AHA guidelines. In VP with hemodynamic or electrical instability, TFA is more frequently undertaken, as low systolic and mean arterial pressure hampers radial artery accessibility, coronary intervention is typically more complex and the need for concomitant hemodynamic support devices is more frequent. Advanced Killip class has been repeatedly identified among the main causes of radial failure.12–14 However, over the last few years, experience and emerging techniques have facilitated the use of TRA. A large analysis of the NCDR CathPCI Registry in 692 433 STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI explored the temporal trends of TRA, which increased from 2% in 2009 to 23% in 2015, with significant geographic variation.15 Age, sex, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, operators entering practice before 2012, and nonacademically affiliated institutions were all associated with lower rates of TRA.15 Among the 7231 patients with advanced Killip class in the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society database, TFA was used in 5354 and TRA in 1877 patients. TRA was independently associated with lower 30-day mortality, in-hospital MACE and major bleeding.16 In the present study, we observed that TRA remained associated with consistent benefits in VP compared with non-VP, with a treatment effect on absolute basis being larger in the former compared with the latter group. A reasonable interpretation of our findings is that use of TRA does not seem to be associated with specific penalties in VP, who suffer from greater absolute risks and derive a higher absolute risk reduction from this intervention. Our observation, therefore, supports the use of TRA as the default access in all ACS patients undergoing invasive management. At subgroup analysis, the effect of TRA vs TFA remained consistent throughout all prespecified covariates with the notable exception of center proportion of radial PCI. Both VP and non-VP groups allocated to TRA in centers with the highest proportion of radial PCI experienced a clinically meaningful reduction in MACE or NACE endpoints compared with TFA. In contrast, in centers with a low or average proportion of radial PCI, TRA was apparently associated with somewhat smaller benefits in non-VP or even a slightly increased risk, especially for MACE, in VP. The current findings should be interpreted by taking into account that operators enrolling in MATRIX had to be adequately trained in both TRA and TFA. This observation has important clinical implications,17reinforcing the notion that especially for VP undergoing invasive management, TRA should be the default access site only if performed by routine radial operators. Conversely, less expert centers/operators might further expand their training by selecting TRA in less vulnerable patients.

Antithrombin type in patients with hemodynamic or electrical vulnerabilityData comparing bivalirudin with UFH in ACS patients with HF and/or OHCA are limited.18 Some evidence suggests that chronic HF, independent of atherosclerosis and ACS, is associated with elevated thrombin levels and faster formation of compact, resistant fibrin clots, and therefore bivalirudin might be even more beneficial in these patients.4,5 In the EUROMAX, there was no significant interaction for the primary endpoint across patients with Killip class I vs II-IV, but this latter group was small (77 and 69 in the bivalirudin and heparin groups, respectively).19 In the HEAT-PPCI, the primary endpoint was consistent across stratification according to left ventricular function impairment (defined by left ventricle ejection fraction< 55%).20 Pinto et al.5 reported an analysis of the Premier Hospital Database comparing the use of bivalirudin and heparin in more than 116 000 congestive HF patients undergoing PCI. In-hospital mortality, which was the primary outcome of the study, was lower for bivalirudin monotherapy (2.3%) compared with heparin monotherapy (4.8%). In a matched propensity-score analysis, a mortality benefit remained associated with the use of bivalirudin compared with heparin. Bivalirudin therapy was also associated with lower bleeding or transfusion rates, as well as shorter hospitalizations.5

In the MATRIX trial, bivalirudin failed to significantly reduce the composite coprimary endpoints compared with UFH, but was associated with lower rates of major bleeding and all-cause mortality, irrespective of GPI use in the comparator arm.7,21 In the current analysis, we observed that VP showed greater absolute benefits from bivalirudin compared with UFH with respect to both coprimary endpoints, likely reflecting the higher event rates observed in these patients. The trends in favor of bivalirudin in VP at interaction testing for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular fatalities or major bleeding might suggest that a direct compared with an indirect thrombin inhibitor might be particularly beneficial in this selected population. The significant reduction of mortality and cardiovascular mortality, despite a trend toward higher MI, with bivalirudin observed in VP, might be attributed to the greater benefit derived by these patients in terms of major bleeding, and partially to the trend in lower stroke rates compared with the non-VP group. However, our analyses remain inconclusive and at best hypothesis generating. Subgroup analyses showed that prior administration of UFH but not ticagrelor or prasugrel might further optimize the MACE or NACE endpoints compared with UFH in VP, which is at variance with the corresponding observation in the non-VP group. The notion that the uptake of even newer P2Y12 oral inhibitors is particularly delayed in VP22 may provide a possible mechanistic explanation for our current findings, which altogether reinforce the message that parenteral strategies (ie, cangrelor or short glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors infusion or prolonged bivalirudin at full PCI dose)22–24 more than oral antiplatelet agents might be prioritized in VP.

LimitationsThis is a post hoc analysis of the MATRIX trial, which was not powered to investigate the effects of the experimental treatment strategies in the VP subgroup. Our results should be interpreted in the context of uncontrolled Type I and Type II errors and regarded as hypothesis generating. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, increasing the risk of type I error. The MATRIX study did not exclude patients based on advanced Killip class or OHCA at presentation. Nevertheless, it remains unknown if and how much this high-risk patient category was consecutively included in the study. The requirement of written informed consent before patient participation obviously skewed inclusion toward conscious and collaborative patients only, to whom our results should apply. Even so, the proportion of VP (11.1%) compares favorably with many other previous ACS studies, which almost completely excluded them from inclusion.

Our definition of VP was not prespecified and encompasses a heterogeneous patient population and only a few patients with overt cardiogenic shock (Killip class IV) were included at the time of PCI.

CONCLUSIONSIn patients with ACS undergoing invasive management, the effects of radial vs femoral and bivalirudin vs unfractionated heparin were consistent in patients with or without hemodynamic and/or electrical vulnerability. Absolute event rates were greater in VP, and both TRA and bivalirudin were associated with greater absolute risk reduction for both ischemic and bleeding endpoints in this patient subset compared with TFA or UFH, respectively.

- -

Compared with TFA, TRA has various advantages and is currently the recommended approach in ACS patients undergoing PCI.

- -

Concerns have been raised particularly among patients with hemodynamic (advanced Killip class) or electrical (OHCA survivors) vulnerability (HVP) in whom TFA may constitute a more reliable and quicker access to reach a diagnosis and deliver timely treatment.

- -

In these patients the optimal antithrombotic therapy is also uncertain.

- -

In this large and contemporary randomized clinical trial, vulnerable patients (VP: 9.6% with acute HF and 2.0% with OHCA, with 0.5% exhibiting both conditions) more frequently had cardiovascular risk factors, more frequently fulfilled procedural complexity criteria and experienced a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes compared with non-VP.

- -

Radial access was associated with a consistent relative risk reduction of composite primary as well as key secondary endpoints, including mortality and severe bleeding events in VP and non-VP groups compared with TFA. However, since the event rate was much higher in VP, these patients experienced a larger absolute risk reduction with TFA.

- -

The comparative safety and effectiveness of bivalirudin vs UFH were consistent between VP and non-VP, with greater absolute bivalirudin-related benefits in the former compared with the latter group.

The trial was sponsored by the Società Italiana di Cardiologia Invasiva (GISE), a nonprofit organization, which received grant support from the Medicines Company and Terumo. The current analysis did not receive any direct or indirect funding. The sponsor and companies had no role in study design, data collection, data monitoring, analysis, interpretation, or drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestM. Sunnåker is affiliated with CTU Bern, University of Bern, which has a staff policy of not accepting honoraria or consultancy fees. The conflicts of interest of CTU Bern can be found on the University website. P. Vranckx reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca and the Medicines Company during the study; speaking or consulting fees from Bayer, Health Care, Terumo and Daiichi-Sankyo outside the submitted work. S. Leonardi reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi and the Medicines Company during the study and outside the submitted work. S. Windecker reports research contracts to the institution from Abbott, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, St Jude and Terumo. M. Valgimigli reports grants from the Medicines Company, grants from Terumo, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees and nonfinancial support from the Medicines Company, personal fees from Terumo, St Jude Vascular, Alvimedica, Abbott Vascular, and Correvio, outside the submitted work.

Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2020.01.005