Current guidelines on the treatment of blood cholesterol recommend continuous maintenance of high-intensity statin treatment in drug-eluting stent (DES)-treated patients. However, high-intensity statin treatment is frequently underused in clinical practice after stabilization of DES-treated patients. Currently, the impact of continuous high-intensity statin treatment on the incidence of late adverse events in these patients is unknown. We investigated whether high-intensity statin treatment reduces late adverse events in clinically stable patients on aspirin monotherapy 12 months after DES implantation.

MethodsClinically stable patients who underwent DES implantation 12 months previously and received aspirin monotherapy were randomly assigned to receive either high-intensity (40mg atorvastatin, n = 1000) or low-intensity (20mg pravastatin, n = 1000) statin treatment. The primary endpoint was adverse clinical events at 12-month follow-up (a composite of all death, myocardial infarction, revascularization, stent thrombosis, stroke, renal deterioration, intervention for peripheral artery disease, and admission for cardiac events).

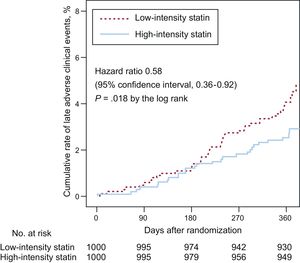

ResultsThe primary endpoint at 12-month follow-up occurred in 25 patients (2.5%) receiving high-intensity statin treatment and in 40 patients (4.1%) receiving low-intensity statin treatment (HR, 0.58; 95%CI, 0.36-0.92; P = .018). This difference was mainly driven by a lower rate of cardiac death (0 vs 0.4%, P = .025) and nontarget vessel myocardial infarction (0.1 vs 0.7%, P = .033) in the high-intensity statin treatment group.

ConclusionsAmong clinically stable DES-treated patients on aspirin monotherapy, high-intensity statin treatment significantly reduced late adverse events compared with low-intensity statin treatment.

Clinical trial registration: URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01557075.

Keywords

Drug-eluting stents (DES) have been continuously improved to lower rates of associated adverse clinical events.1,2 Randomized trials and meta-analyses have shown that new-generation DES have better safety and efficacy than first-generation DES.3 However, late adverse clinical events (> 12 months after DES implantation), such as very late stent thrombosis or the late catch-up phenomenon, still occur in patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with new-generation DES1 due to complications such as chronic inflammation, delayed neointimal healing, and neoatherosclerosis.4–6 Approaches to preventing these late complications have not been clearly established. Although prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy lasting > 12 months after DES implantation can be considered,7 a higher incidence of bleeding events has been linked to increased all-cause mortality in DES-treated patients.8

High-intensity statin treatment can reduce coronary morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. These protective effects of statins are related not only to reduced levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol6 but also to their pleiotropic effects, such as reduced inflammation,9,10 antiplatelet/antithrombotic activity,11,12 improvement in endothelial function,13,14 suppression of plaque progression,15 and stabilization of vulnerable plaques.16 Statin treatment can also accelerate stent strut coverage after DES implantation13,17 and reduce blood viscosity, thereby decreasing wall shear stress and preventing plaque rupture.18 Furthermore, a recent study suggests that an intensive reduction in lipid level can have favorable effects on qualitative aspects of neointimal tissue after DES implantation.19

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on the treatment of blood cholesterol recommend continuous maintenance of high-intensity statin treatment in DES-treated patients.20–22 However, high-intensity statin treatment is frequently underused in clinical practice after stabilization of DES-treated patients.23,24 These patients are sometimes treated with low-intensity statin therapy. Therefore, we evaluated the impact of continuous high-intensity statin treatment on late adverse events in clinically stable DES-treated patients on aspirin monotherapy.

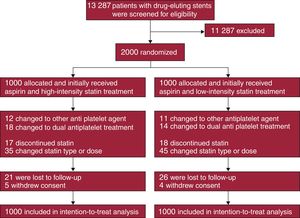

METHODSStudy Design and ParticipantsThis was an investigator-initiated, open-label, randomized, parallel, multicenter study conducted at 15 centers in Korea. Clinically stable patients who underwent DES implantation approximately 12 months previously and who subsequently received aspirin monotherapy with discontinuation of clopidogrel were enrolled between August 2010 and November 2014. Patients were not eligible if they: a) experienced adverse clinical events within 12 months after DES implantation, b) currently received single or dual antiplatelet therapy other than aspirin, c) were allergic to or experienced adverse effects of aspirin or statins, d) were < 20 years old, e) were pregnant, f) had a life expectancy ≤ 2 years, or g) had an indication for prolonged high-intensity statin treatment. Using an interactive web-based system, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive high-intensity statin treatment (atorvastatin, 40mg/d) or low-intensity statin treatment (pravastatin, 20mg/d) with the use of a block size of 4 for the 2 study groups. Atorvastatin and pravastatin are commonly prescribed statins in Korea. Concealed randomization was stratified based on the enrolling sites and the presence of acute coronary syndrome at the index PCI. The investigators, patients, data analysts, and the trial funder were blind to the randomization sequence. Enrollment was performed by treating physicians. Immediately after randomization, the treating physicians prescribed the assigned statins to the patients. Therefore, all enrolled patients initially received the assigned treatment (Figure 1). Neither the patients nor the treating physicians were blind to the assigned treatment. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center, and all patients provided written informed consent. Study coordination, data management, and site management were carried out by a clinical data management center (Cardiovascular Research Center, Seoul, Korea). The designated trial monitors reviewed the data for accuracy and completeness at appropriate intervals and ensured compliance with the study protocol, which was unchanged during the course of the study. A data and safety monitoring board composed of independent physicians with access to the unblinded data monitored the safety of the study.

Study Follow-up and EndpointTo investigate the comprehensive effect of high-intensity statin treatment on reducing various cardiovascular events, the primary endpoint was a composite of adverse clinical events including death from any cause, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, target or nontarget vessel revascularization, stroke, deterioration of renal function, intervention for peripheral artery disease, and admission for significant cardiac events (defined as admission for severe chest pain, dyspnea, edema, palpitation or syncope) at 12-month follow-up. Clinical events were defined according to the Academic Research Consortium.25 All deaths were considered cardiac deaths unless a definite noncardiac cause could be identified. Myocardial infarction was defined as the presence of clinical symptoms, electrocardiographic changes, or abnormal imaging findings of myocardial infarction combined with an increase in creatine kinase myocardial band fraction above the upper normal limits or an increase in troponin T or troponin I to a level greater than the 99th percentile of the upper normal limit. If the territory of the myocardial infarction was supplied by the coronary artery containing the implanted DES, it was defined as target vessel-related myocardial infarction. Definite, probable, and possible stent thrombosis were defined according to recommendations of the Academic Research Consortium.25 Target or nontarget vessel revascularization was defined as repeat PCI or bypass surgery of the target vessel or as PCI or bypass surgery of the nontarget vessel with either of the following: a) ischemic symptoms or a positive stress test and angiographic diameter stenosis ≥ 50% by quantitative coronary angiographic analysis, or b) angiographic diameter stenosis ≥ 70% by quantitative coronary angiographic analysis without ischemic symptoms or a positive stress test. Deterioration of renal function was defined as an increase of > 25% or > 0.5mg/dL in serum creatinine level. Stroke, as detected by the occurrence of a new neurological deficit, was confirmed by neurological examination and imaging. Assessments for clinical events and medication adherence were performed 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after randomization at physician office visits. Laboratory tests were recommended after randomization and at 12-month follow-up. During the assessments, all data were collected and entered into a computer database by specialists from the clinical data management center. A blinded independent clinical events committee adjudicated all components of the primary endpoint without revising the patients’ original source documents.

Sample Size Calculation and Statistical AnalysisThe sample size calculation was based on the primary endpoint. The primary analysis was a superiority comparison of high-intensity statin therapy with low-intensity statin therapy with respect to the occurrence of the primary endpoint. Calculation of the sample size was based on a 2-sample and 2-sided test. From previous studies,26,27 we assumed that the overall incidence of late adverse clinical events would be 4.0% in patients receiving high-intensity statin treatment and 7.0% in those receiving low-intensity statin treatment between 1 and 2 years after DES implantation. We expected that high-intensity statin treatment would reduce the primary endpoint by 50%. With the superiority design, 1000 patients were needed for each arm, assuming a 2-sided alpha level of 0.05, statistical power of 80%, and estimated dropout rate of 10%.

The primary analysis was an intention-to-treat analysis testing whether high-intensity statin treatment was superior to low-intensity statin treatment with respect to the occurrence of the primary endpoint. Cumulative rates of the primary endpoint and its individual components were calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared between the 2 treatment groups using log rank tests. In addition, we estimated hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the association of statin doses with the primary endpoint by using a Cox proportional hazard model, adjusted for enrolling sites and baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics (age, sex, diabetes mellitus, acute coronary syndrome, left ventricular ejection fraction, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, multivessel PCI, DES types, DES sizes). Patients who were lost to follow-up (n = 47, 2.4%) or withdrew consent (n = 9, 0.5%) were assessed at the time they were last known to be event-free. Although patients could experience more than 1 component of the primary endpoints, each patient was assessed only once in the analysis, during the time until the occurrence of their first event. Subgroup analysis was performed according to the prespecified subgroups. It was assessed using interaction terms in a Cox proportional hazard model. Categorical variables are reported as numbers (percentages) and were compared using a chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. Continuous variables are reported as the mean ± standard deviation or the median [interquartile range] and were compared using the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 23, IBM, Chicago, IL). All tests were 2-sided, and P-values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

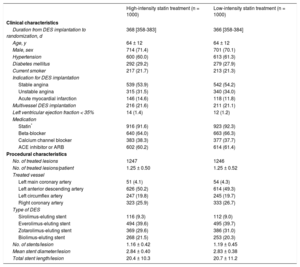

RESULTSPatients were randomly assigned to receive high-intensity statin treatment (n = 1000) or low-intensity statin (n = 1000) treatment (Figure 1). One-year follow-up was completed by 974 patients (97.4%) receiving high-intensity statin treatment and 970 patients (97.0%) receiving low-intensity statin treatment (P = .588). Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics were well balanced between the 2 groups (Table 1). Considering both groups, the median duration from DES implantation to randomization was 367 days [interquartile range: 358–383 days]. Most patients (91%) received new-generation DES.

Baseline Clinical and Procedural Characteristics

| High-intensity statin treatment (n = 1000) | Low-intensity statin treatment (n = 1000) | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Duration from DES implantation to randomization, d | 368 [358-383] | 366 [358-384] |

| Age, y | 64 ± 12 | 64 ± 12 |

| Male, sex | 714 (71.4) | 701 (70.1) |

| Hypertension | 600 (60.0) | 613 (61.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 292 (29.2) | 279 (27.9) |

| Current smoker | 217 (21.7) | 213 (21.3) |

| Indication for DES implantation | ||

| Stable angina | 539 (53.9) | 542 (54.2) |

| Unstable angina | 315 (31.5) | 340 (34.0) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 146 (14.6) | 118 (11.8) |

| Multivessel DES implantation | 216 (21.6) | 211 (21.1) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction < 35% | 14 (1.4) | 12 (1.2) |

| Medication | ||

| Statin* | 916 (91.6) | 923 (92.3) |

| Beta-blocker | 640 (64.0) | 663 (66.3) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 383 (38.3) | 377 (37.7) |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 602 (60.2) | 614 (61.4) |

| Procedural characteristics | ||

| No. of treated lesions | 1247 | 1246 |

| No. of treated lesions/patient | 1.25 ± 0.50 | 1.25 ± 0.52 |

| Treated vessel | ||

| Left main coronary artery | 51 (4.1) | 54 (4.3) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 626 (50.2) | 614 (49.3) |

| Left circumflex artery | 247 (19.8) | 245 (19.7) |

| Right coronary artery | 323 (25.9) | 333 (26.7) |

| Type of DES | ||

| Sirolimus-eluting stent | 116 (9.3) | 112 (9.0) |

| Everolimus-eluting stent | 494 (39.6) | 495 (39.7) |

| Zotarolimus-eluting stent | 369 (29.6) | 386 (31.0) |

| Biolimus-eluting stent | 268 (21.5) | 253 (20.3) |

| No. of stents/lesion | 1.16 ± 0.42 | 1.19 ± 0.45 |

| Mean stent diameter/lesion | 2.84 ± 0.40 | 2.83 ± 0.38 |

| Total stent length/lesion | 20.4 ± 10.3 | 20.7 ± 11.2 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DES, drug-eluting stent.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

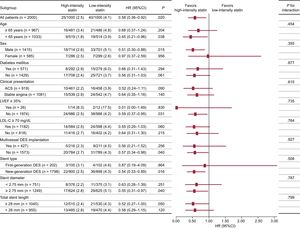

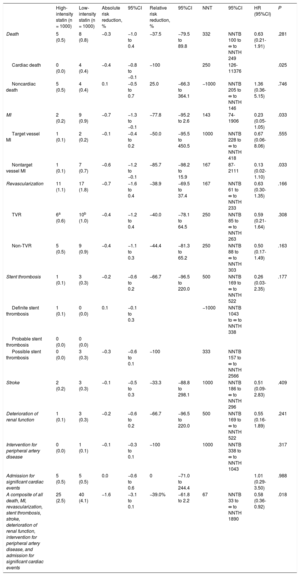

The primary endpoint at 12-month follow-up occurred in 25 patients (2.5%) receiving high-intensity statin treatment and 40 patients (4.1%) receiving low-intensity statin treatment (hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-0.92; P = .018 using a log rank test; Figure 2). The difference was mainly driven by a lower rate of cardiac death (0% vs 0.4%, P = .025) and nontarget vessel myocardial infarction (0.1% vs 0.7%, P = .033) in patients with high-intensity statin treatment (Table 2). Prespecified subgroup analyses showed no statistically significant interactions of statin treatment with clinical or angiographic characteristics (Figure 3).

Clinical Outcomes at 12 Months

| High-intensity statin (n = 1000) | Low-intensity statin (n = 1000) | Absolute risk reduction, % | 95%CI | Relative risk reduction, % | 95%CI | NNT | 95%CI | HR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 5 (0.5) | 8 (0.8) | −0.3 | −1.0 to 0.4 | −37.5 | −79.5 to 89.8 | 332 | NNTB 100 to ∞ to NNTH 249 | 0.63 (0.21-1.91) | .281 |

| Cardiac death | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) | −0.4 | −0.8 to −0.1 | −100 | 250 | 126-11376 | .025 | ||

| Noncardiac death | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 0.1 | −0.5 to 0.7 | 25.0 | −66.3 to 364.1 | −1000 | NNTB 205 to ∞ to NNTH 146 | 1.36 (0.36-5.15) | .746 |

| MI | 2 (0.2) | 9 (0.9) | −0.7 | −1.3 to −0.1 | −77.8 | −95.2 to 2.6 | 143 | 74-1906 | 0.23 (0.05-1.05) | .033 |

| Target vessel MI | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | −0.1 | −0.4 to 0.2 | −50.0 | −95.5 to 450.5 | 1000 | NNTB 228 to ∞ to NNTH 418 | 0.67 (0.06-8.06) | .555 |

| Nontarget vessel MI | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.7) | −0.6 | −1.2 to −0.1 | −85.7 | −98.2 to 15.9 | 167 | 87-2111 | 0.13 (0.02-1.10) | .033 |

| Revascularization | 11 (1.1) | 17 (1.8) | −0.7 | −1.6 to 0.4 | −38.9 | −69.5 to 37.4 | 167 | NNTB 61 to ∞ to NNTH 233 | 0.63 (0.30-1.35) | .166 |

| TVR | 6a (0.6) | 10b (1.0) | −0.4 | −1.2 to 0.4 | −40.0 | −78.1 to 64.5 | 250 | NNTB 85 to ∞ to NNTH 263 | 0.59 (0.21-1.64) | .308 |

| Non-TVR | 5 (0.5) | 9 (0.9) | −0.4 | −1.1 to 0.3 | −44.4 | −81.3 to 65.2 | 250 | NNTB 88 to ∞ to NNTH 303 | 0.50 (0.17-1.49) | .163 |

| Stent thrombosis | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | −0.2 | −0.6 to 0.2 | −66.7 | −96.5 to 220.0 | 500 | NNTB 169 to ∞ to NNTH 522 | 0.26 (0.03-2.35) | .177 |

| Definite stent thrombosis | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1 | −0.1 to 0.3 | −1000 | NNTB 1043 to ∞ to NNTH 338 | ||||

| Probable stent thrombosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||||

| Possible stent thrombosis | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | −0.3 | −0.6 to 0.1 | −100 | 333 | NNTB 157 to ∞ to NNTH 2566 | |||

| Stroke | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | −0.1 | −0.5 to 0.3 | −33.3 | −88.8 to 298.1 | 1000 | NNTB 186 to ∞ to NNTH 296 | 0.51 (0.09-2.83) | .409 |

| Deterioration of renal function | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | −0.2 | −0.6 to 0.2 | −66.7 | −96.5 to 220.0 | 500 | NNTB 169 to ∞ to NNTH 522 | 0.55 (0.16-1.89) | .241 |

| Intervention for peripheral artery disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | −0.1 | −0.3 to 0.1 | −100 | 1000 | NNTB 338 to ∞ to NNTH 1043 | .317 | ||

| Admission for significant cardiac events | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 0.0 | −0.6 to 0.6 | 0 | −71.0 to 244.4 | 1.01 (0.29-3.50) | .988 | ||

| A composite of all death, MI, revascularization, stent thrombosis, stroke, deterioration of renal function, intervention for peripheral artery disease, and admission for significant cardiac events | 25 (2.5) | 40 (4.1) | −1.6 | −3.1 to 0.1 | −39.0% | −61.8 to 2.2 | 67 | NNTB 33 to ∞ to NNTH 1890 | 0.58 (0.36-0.92) | .018 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; NNT, number needed to treat; NNTB, NNT to benefit; NNTH, NNT to harm; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as No. (%) (cumulative 12-month event rate).

Subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint at the 12-month follow-up. Data are expressed as No. of events/No. of patients (%) (cumulative 12-month event rate). 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; DES, drug-eluting stent; HR, hazard ratio; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Baseline laboratory parameters were similar between the 2 groups (Table 3). At 12-month follow-up, however, levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein were significantly lower in patients receiving high-intensity statin treatment than in those receiving low-intensity statin treatment. Changes in levels of liver enzymes, creatinine, and creatine kinase between baseline and 12-month follow-up were similar between the 2 groups. The incidence of statin discontinuation was also similar between the 2 groups (17 patients with high-intensity statin treatment vs 18 patients with low-intensity statin treatment, Figure 1). New-onset diabetes mellitus requiring treatment with oral hypoglycemic agents was observed in 10 of 708 patients (1.4%) receiving high-intensity statin treatment and 6 of 721 patients (0.8%) receiving low-intensity statin treatment (P = .297).

Blood Laboratory Measures at Baseline and 12-month Follow-up

| Measurements | Baseline | 12-month follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-intensity statin treatment | Low-intensity statin treatment | High-intensity statin treatment | Low-intensity statin treatment | P | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 142.2 ± 31.5 | 143.9 ± 32.6 | 134.6 ± 29.4 | 172.7 ± 34.3 | < .001 |

| Change at follow-up | −5.9 ± 28.9 | 29.9 ± 31.9 | < .001 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −35.8 | (−40.0 to −31.6) | |||

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 132.7 ± 80.8 | 135.5 ± 85.7 | 119.1 ± 70.6 | 154.0 ± 103.3 | < .001 |

| Change at follow-up | −10.4 ± 71.0 | 25.0 ± 97.5 | < .001 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −35.4 | (−47.5 to −23.3) | |||

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 44.2 ± 10.5 | 44.1 ± 9.9 | 44.1 ± 10.3 | 45.3 ± 11.2 | .058 |

| Change at follow-up | −0.5 ± 8.0 | 0.8 ± 8.2 | .063 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −1.3 | (−2.5 to −0.1) | |||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 74.1 ± 27.6 | 74.2 ± 26.4 | 67.8 ± 23.0 | 98.8 ± 28.8 | < .001 |

| Change at follow-up | −5.3 ± 24.9 | 25.9 ± 25.7 | < .001 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −31.2 | (−35.0 to −27.4) | |||

| White blood cell, 103/μL | 6.9 ± 2.2 | 6.9 ± 2.0 | 6.8 ± 1.9 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | .433 |

| Change at follow-up | 0.03 ± 1.8 | 0.05 ± 1.6 | .829 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −0.02 | (−0.3 to 0.2) | |||

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 1.8 ± 4.3 | 1.7 ± 3.9 | 1.4 ± 3.0 | 2.3 ± 5.3 | .002 |

| Change at follow-up | −0.3 ± 5.1 | 0.6 ± 6.2 | .017 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −0.9 | (−1.7 to −0.1) | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.96 ± 0.42 | 0.95 ± 0.49 | 0.94 ± 0.39 | 0.94 ± 0.49 | .936 |

| Change at follow-up | −0.02 ± 0.17 | 0.01 ± 0.17 | .143 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −0.03 | (−0.06 to 0.01) | |||

| Aspartate transaminase, U/L | 25.9 ± 13.1 | 25.5 ± 13.2 | 25.7 ± 14.5 | 25.0 ± 14.1 | .451 |

| Change at follow-up | 0.0 ± 10.3 | −0.2 ± 18.0 | .851 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | 0.2 | (−1.9 to 2.3) | |||

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | 26.7 ± 15.6 | 26.7 ± 25.7 | 26.5 ± 14.8 | 26.0 ± 17.1 | .621 |

| Change at follow-up | −0.8 ± 14.3 | −0.6 ± 29.9 | .906 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | −0.2 | (−3.6 to 3.2) | |||

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 125.5 ± 91.9 | 123.6 ± 168.6 | 131.6 ± 143.2 | 128.5 ± 83.0 | .678 |

| Change at follow-up | 13.2 ± 158.9 | 4.0 ± 197.2 | .531 | ||

| Difference in change (95%CI) | 9.2 | (−19.7 to 38.1) | |||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

In this randomized multicenter trial, high-intensity compared with low-intensity statin treatment significantly reduced late adverse events among clinically stable patients who underwent DES implantation 12 months previously and who received aspirin monotherapy after clopidogrel discontinuation.

Two earlier studies have also demonstrated that high-intensity statin treatment reduces long-term clinical events in patients with previous PCI more effectively than low-intensity or standard statin treatment.26,27 The Treating to New Targets study, which included 5407 patients who underwent PCI for stable coronary disease, showed that treatment with 80mg/d atorvastatin significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events (ie, death from coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, and stroke) by 21% and repeat revascularization by 27% compared with treatment with 10mg/d atorvastatin during a median follow-up period of 4.9 years.27 The PCI-PROVE IT study, which included 2867 patients who underwent PCI for acute coronary syndrome, also showed that treatment with 80mg/d atorvastatin significantly reduced the incidence of the primary endpoint (ie, composite of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, revascularization, stroke, and rehospitalization) by 22% and repeat revascularization by 24% compared with treatment with 40mg/d pravastatin.26 However, both studies were conducted in the era of bare-metal stents, whereas significant improvements in PCI-related equipment, techniques, and pharmacology have occurred alongside the development of DES. Therefore, clinical data relevant to our current predominant use of DES in daily practice are required. The present study included patients who were exclusively treated with DES, with most (90%) being new-generation DES. Therefore, our study more closely reflects the reality of current clinical practice.

In real-world practice, high-intensity statin treatment is underused. For instance, high-intensity statin treatment is maintained in only 14% of patients with acute coronary syndrome who underwent PCI in Korea.23 In addition, high-intensity statin treatment is prescribed for only 35% of patients with coronary events (ie, myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization) within 12 months after hospital discharge in the United States.24 Factors that might contribute to the underuse of high-intensity statin treatment include stable angina rather than myocardial infarction, achievement of low lipid levels at discharge, cost barriers, post-discharge transitions including transfers, concerns about high-intensity statin-related adverse effects, combined hepatic/renal comorbidities, pre-event adherence to low/intermediate-intensity statins, and medication reconciliation between patients and physicians.23,24 However, statin dose-related concerns such as new-onset diabetes (50-100 per 10 000 patients), myopathy (5 per 10 000 patients), severe hepatic injury (1 per 100 000 patients), or deterioration of renal function are rare or not supported by evidence.28 Furthermore, the harmful effects of statins can be reversed by stopping treatment, whereas cardiac or vascular events due to statin underuse can be devastating.28 In the present study, we exclusively enrolled patients who were successfully treated with DES 12 months previously and were then safely switched to aspirin monotherapy without adverse clinical events. As these patients are assumed to be at low risk for late adverse events, there could be reluctance to maintain high-intensity statin treatment, leading to the underuse of high-intensity statin treatment in real-world practice. However, we found that high-intensity statin treatment significantly reduced late adverse clinical events by 42% compared with low-intensity statin treatment. Therefore, high-intensity statin treatment is strongly recommended even in clinically stable DES-treated patients on aspirin monotherapy.

Because most patients (92%) receiving high-intensity statin treatment had already been taking high- or intermediate-intensity statins at the time of enrollment, their baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were low, and further decreases during the 12-month follow-up were minimal. On the other hand, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients receiving low-intensity statin treatment increased during the 12-month follow-up, likely due to the relatively weak potency of pravastatin.29 Also, high-intensity statin treatment reduced high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels more effectively than low-intensity statin treatment. These findings suggest that a reduction of late adverse clinical events is mediated by the lipid-lowering and pleiotropic (eg, anti-inflammatory) effects of high-intensity statin treatment.26

In the present study, unexplained sudden death, defined as cardiac death and possible stent thrombosis, occurred in 3 patients receiving low-intensity statin treatment. By contrast, no such event occurred in patients receiving high-intensity statin treatment, perhaps because high-intensity statin treatment can prevent delayed vascular healing processes and chronic vascular inflammation, which are predisposing factors for very late stent thrombosis,4 after DES implantation.6,10,17 We also observed a lower incidence of nontarget vessel myocardial infarction in patients receiving high-intensity statin treatment, which might be explained by plaque stabilization and suppression of plaque progression.15,16

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, the observed overall event rate of the primary endpoint was lower than anticipated. This may be because the expected event rate and sample size calculations were based on previous studies performed in the era of bare-metal stents, whereas the improved performance of contemporary DES may have lowered the rate of adverse clinical events. Second, only stable patients who had not experienced any adverse events within 12 months after DES implantation were enrolled. Thus, more inclusive studies are warranted to evaluate the effectiveness of high-intensity statin treatment for secondary prevention of adverse clinical events. Third, a 12-month follow-up is a relatively short time span for evaluating the impact of high-intensity statin treatment on clinical outcomes in stable DES-treated patients. Fourth, this was an open-label study. Fifth, each treatment group was treated with different statins (atorvastatin vs pravastatin). Sixth, statin-related adverse effects such as myopathy and hepatic injury were not clearly evaluated.

CONCLUSIONSContinuous maintenance of high-intensity statin treatment should be considered even in clinically stable DES-treated patients on aspirin monotherapy with a low risk of adverse events.

FUNDINGThis study was supported by grants from the Korea Healthcare Technology Research & Development Project, Ministry for Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Nos. A085136 and H115C1277), the Mid-career Researcher Program through the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, & Technology, Republic of Korea (No. 2015R1A2A2A01002731), Yuhan Corporation, Korea, CJ HealthCare, Korea, Daiichi Sankyo Korea Co, Ltd and the Cardiovascular Research Center, Seoul, Korea.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Current guidelines recommend continuous maintenance of high-intensity statin treatment for patients who are treated with DES. However, high-intensity statin treatment is frequently underused in clinical practice after stabilization of DES-treated patients.

- –

Among clinically stable DES-treated patients on aspirin monotherapy, high-intensity statin treatment significantly reduced late adverse clinical events compared with low-intensity statin treatment over a 12-month follow-up.

.