The benefit of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade on mortality and morbidity in patients with acute myocardial infarction, especially with left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction, is well known. However, the data are largely drawn from an era when percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) rates in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were very low, and when most patients may not have been on currently-recommended optimal medical therapy, including dual antiplatelet therapy and high-intensity statins.1–3

Therefore, in a recent article published in Revista Española de Cardiología, Raposeiras-Roubín et al. examined the association between RAS blockade at hospital discharge and 1-year mortality in an observational study of 15401 ACS patients post-PCI, enrolled in the multicenter BLEEMACS registry from November 2003 through June 2014.4 Patients were enrolled in the registry from North (Canada) and South America (Brazil), Europe, and Asia (China, Japan). Seventy-five percent of the patients were discharged on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). There were significant differences in the baseline characteristics of patients who were prescribed RAS blockade at discharge and those who were not. Compared with patients discharged on ACEIs/ARBs, those discharged without these drugs appeared to have a lower comorbidity burden as well as a lower cardiovascular risk profile. For example, 25% of patients had diabetes mellitus and 61% had hypertension among those discharged on ACEIs/ARBs, whereas 22% had diabetes and 50% had hypertension in those discharged without ACEIs/ARBs. A similar difference was noted for dyslipidemia between the 2 arms. Also, a higher proportion of patients discharged on ACEIs or ARBs had LV systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≤ 40%; 16.1%) compared with those discharged without RAS blockade (11.9%). Of note, beta-blockers and statins were also more frequently prescribed in the group prescribed RAS blockade. Given these significant baseline imbalances between the 2 groups, in addition to traditional analyses with multivariate adjustment of time to event hazards modeling, the investigators also performed sophisticated propensity matched analyses. Of note, propensity matching reduced the size of the study group from 15401 to 7530 (3765 patients each in the RAS blockade vs no RAS blockade arms).

The overall analysis in this ACS cohort post-PCI demonstrated a significant relative risk reduction (RRR) of 23% (P=.001) associated with the use of RAS blockade. However, on subgroup analysis by LVEF, a significant association was found between reduced mortality and the use of ACEIs or ARBs in patients with LVEF ≤ 40% (RRR of 43% in 1 year mortality) compared with an inconsistent association in patients with LVEF >40% (P value for interaction by ejection fraction group=.008). Furthermore, in the group with LVEF> 40%, RAS blockade was associated with a 56% RRR in mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), while no significant benefit was seen in patients with non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). In patients with LVEF> 40%, but with at least 1 higher risk marker including diabetes, heart failure (HF), hypertension or renal insufficiency, a trend for lower mortality with ACEIs was seen but this difference was not statistically significant (P=.09). Taken together, the data suggest that patients at highest risk, especially patients with LV systolic dysfunction and those with STEMI, appeared to derive the most benefit from RAS blockade.

The findings of this observational study should be evaluated in light of the limitations associated with the study design. Patients were not randomized to the treatment arm of RAS blockade vs no RAS blockade, with major differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups. About 75% of patients were prescribed ACEIs at discharge, and the reasons for use or nonuse of RAS blockade were not known. Despite exhaustive multivariate adjustment and propensity matching, there may be residual confounding, including confounding by indication for the use of these agents at baseline. Furthermore, the study had a relatively short follow-up of 1 year. Only all-cause mortality was examined and outcomes such HF hospitalizations were not evaluated. Furthermore, the lower 1-year postdischarge mortality in patients with LVEF> 40% of 3.1% (6.9% in LVEF ≤ 40%), along with the sample size, may have hampered detection of smaller differences.

How do we put the results of this observational study in the context of prior published studies, including randomized clinical trials forming the basis of practice guidelines? The data are strong for the benefit of ACEIs (or ARBs in patients intolerant to ACEIs) on short- and long-term mortality and other cardiovascular and HF outcomes including postmyocardial infarction with reduced LVEF, HF after myocardial infarction irrespective of LVEF, and after anterior STEMI. These date are based on the results of randomized clinical trials.1–3,5 In addition, a meta-analysis of the acute myocardial infarction trials with ACEIs showed a consistent early benefit in the short-term when the medications were started early after myocardial infarction.1 Furthermore, data demonstrating a consistent benefit of ACEIs and ARBs from trials in chronic HF with reduced LVEF have also been extrapolated for chronic benefit in patients with acute myocardial infarction and reduced LVEF.6

In contrast, there are no data exclusively from clinical trials for the benefit of RAS blockade on longer term outcomes after myocardial infarction in patients with nonanterior wall myocardial infarction, those with preserved LVEF, and those without HF. In 3 large randomized trials examining the role of ACEIs in patients with risk factors for atherosclerotic disease or with established chronic atherosclerotic disease, the benefits of RAS blockade were noted in the higher risk patients,7–9 but were not found in the trial in low-risk patients with coronary artery disease, most whom had been revascularized and were treated with aggressive medical therapy including lipid-lowering therapies.9

The clinical trial data appear to be concordant with well-grounded hypotheses and research demonstrating that the degree of LV dysfunction is one of the most important prognostic factors in survivors of myocardial infarction. After the initial insult, residual viable myocardial tissue undergoes further remodeling and dilation, leading to worsening of LV function. The degree of LV dysfunction is dictated by the size and age of the scar.3,4 Clinical studies have demonstrated that this LV dysfunction and dilation is attenuated by RAS blockade via ACEIs/ARBs.5,10 Moreover, these drugs may have anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic and anti-atherogenic properties that may reduce the risk of recurrent ACS episodes.3,4,6,11

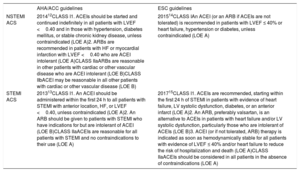

A caveat to the data from the clinical trials discussed above is that they are from an era before the frequent use of PCI for revascularization in ACS, and when patients may not have been on optimal medical therapy including dual antiplatelet therapy and statins. However, the consistent and significant benefit noted in these clinical trials forms the basis for the current recommendations for use of RAS blockade in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI ACS. The current guideline recommendations for use of these agents in both the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology as well as the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for NSTEMI and STEMI are summarized in table 1.12–15

AHA/ACC and ESC Cardiology guidelines for the use of ACEIs and ARBs in patients with ACS

| AHA/ACC guidelines | ESC guidelines | |

|---|---|---|

| NSTEMI ACS | 201412CLASS I1. ACEIs should be started and continued indefinitely in all patients with LVEF <0.40 and in those with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or stable chronic kidney disease, unless contraindicated (LOE A)2. ARBs are recommended in patients with HF or myocardial infarction with LVEF <0.40 who are ACEI intolerant (LOE A)CLASS IIaARBs are reasonable in other patients with cardiac or other vascular disease who are ACEI intolerant (LOE B)CLASS IIbACEI may be reasonable in all other patients with cardiac or other vascular disease (LOE B) | 201514CLASS IAn ACEI (or an ARB if ACEIs are not tolerated) is recommended in patients with LVEF ≤ 40% or heart failure, hypertension or diabetes, unless contraindicated (LOE A) |

| STEMI ACS | 201313CLASS I1. An ACEI should be administered within the first 24 h to all patients with STEMI with anterior location, HF, or LVEF <0.40, unless contraindicated (LOE A)2. An ARB should be given to patients with STEMI who have indications for but are intolerant of ACEI (LOE B)CLASS IIaACEIs are reasonable for all patients with STEMI and no contraindications to their use (LOE A) | 201715CLASS I1. ACEIs are recommended, starting within the first 24 h of STEMI in patients with evidence of heart failure, LV systolic dysfunction, diabetes, or an anterior infarct (LOE A)2. An ARB, preferably valsartan, is an alternative to ACEIs in patients with heart failure and/or LV systolic dysfunction, particularly those who are intolerant of ACEIs (LOE B)3. ACEI (or if not tolerated, ARB) therapy is indicated as soon as hemodynamically stable for all patients with evidence of LVEF ≤ 40% and/or heart failure to reduce the risk of hospitalization and death (LOE A)CLASS IIaACEIs should be considered in all patients in the absence of contraindications (LOE A) |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; HF, heart failure; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; LOE, level of evidence; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI, nonST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

The findings of the current observational study by Raposeiras-Roubín et al. in ACS patients post-PCI, are overall concordant with the guidelines.4 In the higher risk patients, such as those with reduced LVEF (≤ 40%), and patients with STEMI but with preserved LVEF, there was a significant beneficial association of RAS blockade (ACEIs or ARBs) with 1-year mortality. However, the benefit was not seen in the lower risk group with LVEF> 40% with NSTEMI. Although the investigators review some other observational studies examining the same question in the contemporary post-PCI era with some conflicting results, the observational nature of those studies, as well as sample size issues, do not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn. Based on available data, physicians should follow the current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the use of ACEIs and ARBs post-ACS even in patients undergoing revascularization. Prospective clinical trial data in patients with revascularization for NSTEMI with preserved LV function are needed to address the knowledge gap and guide clinical practice in this patient population.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

.