Heart failure (HF) with preserved left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (HFpEF) remains a syndrome or disease with serious consequences for affected individuals.1,2 Large studies have proven that once this syndrome is present, the prognosis of these patients is poor.1,2 Thus, research has been conducted to identify the risk factors for this complex and heterogeneous disease. In this respect, several studies have highlighted atrial fibrillation and chronic renal failure, and comorbidities such as overweight, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, as pivotal risk factors for the development of HFpEF.3–9 Nonetheless, despite these interesting and well-designed studies, there is little information on the interaction of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and future risk of HFpEF. In a recent article published in Revista Española de Cardiología, Cordero et al.10 provide new insights concerning the risk of HFpEF in this study population by analyzing a large cohort of patients with ACS.

Well-recognized risk factors for HF with reduced LV ejection fraction are a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction .3,6,7 However, on the other hand, little is known about the role of CAD in the setting of HFpEF. Recent studies, nonetheless, have suggested that a history of myocardial infarction could be significantly linked to the risk of HFpEF6,8,9 and that revascularization in patients with CAD could be associated with a better prognosis in HFpEF.11 Moreover, analyzing a large cohort of 5962 patients with ACS and preserved LV ejection fraction (LVEF) without previous HF, Cordero et al.10 have shown that the prevalence of new onset HF was 9.5% during a median follow-up of 63 months (with incident HF hospitalization being 2.7% during the first year after ACS). In addition, Cordero et al.10 have also analyzed the concomitant risk factors for incident HF hospitalization after ACS in patients with preserved LVEF (namely, incident HFpEF). In this regard, atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus emerged as the main risk factors for incident HFpEF in their analysis. The role of atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus for incident HFpEF in an ACS population corroborates and strengthens earlier studies demonstrating the role of these common comorbidities as key risk factors for incident HFpEF in non-ACS populations.3–9 On the basis of previous studies6,8,9 and the findings of Cordero et al., 10 a history of ACS or myocardial infarction should be also considered as a risk factor for HFpEF (table 1). In this regard, one of the possible pathophysiological pathways linking ACS/myocardial infarction and HFpEF could be a subendocardial or midmyocardial fibrosis caused by the ACS/myocardial infarction, which would induce LV longitudinal diastolic and systolic dysfunction with consequent elevated LV filling pressures and therefore HFpEF.12

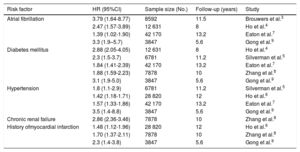

Risk factors associated with the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (ie, incident heart failure with preserved ejection fraction)

| Risk factor | HR (95%CI) | Sample size (No.) | Follow-up (years) | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.79 (1.64-8.77) | 8592 | 11.5 | Brouwers et al.3 |

| 2.47 (1.57-3.89) | 12 631 | 8 | Ho et al.4 | |

| 1.39 (1.02-1.90) | 42 170 | 13.2 | Eaton et al.7 | |

| 3.3 (1.9–5.7) | 3847 | 5.6 | Gong et al.9 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.88 (2.05-4.05) | 12 631 | 8 | Ho et al.4 |

| 2.3 (1.5-3.7) | 6781 | 11.2 | Silverman et al.5 | |

| 1.84 (1.41-2.39) | 42 170 | 13.2 | Eaton et al.7 | |

| 1.88 (1.59-2.23) | 7878 | 10 | Zhang et al.8 | |

| 3.1 (1.9-5.0) | 3847 | 5.6 | Gong et al.9 | |

| Hypertension | 1.8 (1.1-2.9) | 6781 | 11.2 | Silverman et al.5 |

| 1.42 (1.18-1.71) | 28 820 | 12 | Ho et al.6 | |

| 1.57 (1.33-1.86) | 42 170 | 13.2 | Eaton et al.7 | |

| 3.5 (1.4-8.8) | 3847 | 5.6 | Gong et al.9 | |

| Chronic renal failure | 2.86 (2.36-3.46) | 7878 | 10 | Zhang et al.8 |

| History ofmyocardial infarction | 1.48 (1.12-1.96) | 28 820 | 12 | Ho et al.6 |

| 1.70 (1.37-2.11) | 7878 | 10 | Zhang et al.8 | |

| 2.3 (1.4-3.8) | 3847 | 5.6 | Gong et al.9 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Comorbidities also play a key role in the cardiovascular prognosis of patients with HFpEF.12–15 Control and treatment of these comorbidities not only reduces the risk of incident HFpEF but also improves outcomes in these patients.12,15 Indeed, Cordero et al.10 found that optimal medical treatment (defined as the combination of antiplatelets, statins, beta-blockers, and angiotensin-receptor blockers) was associated with a significantly lower risk of HFpEF hospitalization after an ACS. Hence, based on previous studies,1–9,11,13,14 the findings of Cordero et al.10 and the current expert recommendations for the assessment of patients with HFpEF,12,15 optimal management of comorbidities, without underestimating the role of ACS, could have important benefits for this complex and heterogeneous disease, for which, so far, no effective therapies are available to reduce mortality.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTB. Pieske reports personal fees from Bayer Healthcare, Novartis, Merck, Daiichi-Sankyo, NSD, Sanofi-Aventis, Stealth Peptides, and Vifor Pharma. D.A. Morris has no conflicts of interest.