The COVID-19 outbreak has had an unclear impact on the treatment and outcomes of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The aim of this study was to assess changes in STEMI management during the COVID-19 outbreak.

MethodsUsing a multicenter, nationwide, retrospective, observational registry of consecutive patients who were managed in 75 specific STEMI care centers in Spain, we compared patient and procedural characteristics and in-hospital outcomes in 2 different cohorts with 30-day follow-up according to whether the patients had been treated before or after COVID-19.

ResultsSuspected STEMI patients treated in STEMI networks decreased by 27.6% and patients with confirmed STEMI fell from 1305 to 1009 (22.7%). There were no differences in reperfusion strategy (> 94% treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention in both cohorts). Patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention during the COVID-19 outbreak had a longer ischemic time (233 [150-375] vs 200 [140-332] minutes, P<.001) but showed no differences in the time from first medical contact to reperfusion. In-hospital mortality was higher during COVID-19 (7.5% vs 5.1%; unadjusted OR, 1.50; 95%CI, 1.07-2.11; P <.001); this association remained after adjustment for confounders (risk-adjusted OR, 1.88; 95%CI, 1.12-3.14; P=.017). In the 2020 cohort, there was a 6.3% incidence of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during hospitalization.

ConclusionsThe number of STEMI patients treated during the current COVID-19 outbreak fell vs the previous year and there was an increase in the median time from symptom onset to reperfusion and a significant 2-fold increase in the rate of in-hospital mortality. No changes in reperfusion strategy were detected, with primary percutaneous coronary intervention performed for the vast majority of patients. The co-existence of STEMI and SARS-CoV-2 infection was relatively infrequent.

Keywords

On December 31, 2019, a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology was reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. On January 9, 2020, a new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was identified as the causative agent of this outbreak, and its associated disease was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The infection spread rapidly, and the World Health Organization characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11.1 By May 1, 2020, more than 1.6 million cases had been diagnosed in 179 countries on 5 continents, with nearly 100 000 confirmed deaths.1 The Spanish Government activated a State of Emergency on March 14, which restricted the movement of all citizens, except those going to work, to hospitals or health centers, and to financial institutions and those shopping for groceries, pharmaceutics, and basic necessities.2

The impact of this new disease on societal behavior and on health care system performance is unprecedented in recent history. During the current COVID-19 outbreak, some preliminary reports have highlighted a decrease in the number of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients attending hospitals in Europe and North America,3–5 but we have limited information on how the outbreak has affected STEMI networks in terms of delays to reperfusion, revascularization strategies, and clinical outcomes.6,7

The objective of this study was to compare clinical characteristics, management, and hospital outcomes in a nationwide cohort between STEMI patients who attended in the first 30 days after the Spanish lockdown during the current COVID-19 outbreak and those who attended in a period prior to COVID-19.

METHODSSpanish STEMI registryThere are 17 regional public service STEMI care networks in Spain, which comprise 83 hospitals capable of performing primary percutaneous coronary interventions (pPCIs) in year-round 24-hour, 7-day a week programs. In 2018, 21 261 interventions were performed for STEMI (91.6% pPCIs, 3.2% rescue percutaneous coronary interventions, and 5.1% routine early percutaneous coronary interventions strategies after fibrinolysis), representing 417 pPCIs per million population.8

In 2019, the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology sponsored a prospective registry of consecutive STEMI patients who were treated within these specific STEMI care networks. The aim of this Spanish Infarct Code Registry was to detect interregional differences in the management of STEMI. Information was collected on number of cases, clinical characteristics, clinical management, and outcomes of STEMI patients. This registry enrolled 5240 consecutive patients treated between April and June 2019.

During the current COVID-19 outbreak, the Spanish Interventional Cardiology Association established a twin registry involving the retrospective collection of information on all consecutive STEMI patients by the same centers that participated in the 2019 registry. Information was retrospectively recorded on number of cases, clinical characteristics, clinical management, and outcomes from March 16, which was immediately after the activation of the Spanish State of Emergency and the countrywide lockdown.

The research protocol was approved by the Working Group on STEMI Code of the Spanish Interventional Cardiology Association and by a central ethics committee from León and Bierzo Health Areas.

Study designThis multicenter, retrospective, observational cohort study evaluated procedures recorded in the Spanish Infarct Code Registry database to assess whether the current COVID-19 outbreak has had a relevant impact on STEMI treatment in terms of number of cases, clinical characteristics, reperfusion delays, in-hospital management, and in-hospital clinical outcomes. Two different cohorts of patients were established according to whether they had been treated between April 1 and April 30, 2019 (prior to COVID-19 cohort) or between March 16 and April 14, 2020 (during COVID-19 cohort). The analysis included data from 75 hospitals that enrolled patients in both periods. Delay times were defined according to the relevant European guidelines.9 Patients with a final diagnosis other than STEMI were not included in the final analysis. Data were collected through medical record review. The main outcome measure was in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are summarized as mean±standard deviation, whereas categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage. Baseline comparisons between cohorts were performed using t tests or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Variables with highly skewed distributions (ie, times for first medical contact, symptom onset, catheterization laboratory arrival, and reperfusion) are presented as median and interquartile range and were compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Univariate logistic regression models were created to evaluate the association between the cohort group and in-hospital mortality. Multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed to eliminate potential confounders and to assess the consistency of our findings. The covariates included in the multivariate models (symptom onset to reperfusion time, age, sex, Killip class, and a positive polymerase chain reaction [PCR] test for COVID-19) were selected based on medical knowledge and the results of the univariate analysis. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were therefore used to estimate the association between cohort and outcomes.

The robustness of our findings was tested through 2 sensitivity analyses by a) removing COVID-19 individuals from the main analyses to account for their potential contribution to the increase in outcomes; and b) using a mixed regression model including hospital as a random variable, which allowed some heterogeneity in order to take into account the expected variation between hospitals (between-hospital variation), weighting each hospital accordingly to obtain an overall estimate. Two-tailed P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA software version 15.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, United States).

RESULTSPatientsSTEMI networks from 75 hospitals attended a total of 1113 patients during the COVID-19 outbreak, whereas 1538 individuals were treated in the same period the previous year, representing a drop of 27.6%. A flowchart of patients treated in the STEMI networks in the 2 time periods is shown in figure 1. Patients with confirmed STEMI diagnosis comprised 1009 and 1305, respectively (a fall of 22.7%). The trend was consistent among centers (65 of the 75 centers [87%] reported fewer STEMI events). There were also significant differences in the number of patients who required STEMI network assistance but were ultimately diagnosed with a non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: 232 individuals (15.1%) in 2019 but 104 individuals (9.3%) in 2020 (P <.001).

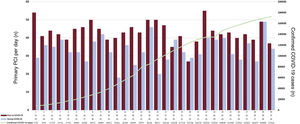

Figure 2 shows the absolute number of pPCIs per day during both time periods and the official number of confirmed cases according to Spanish government data.7

Absolute number of primary percutaneous coronary interventions per day during both time periods and the official number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases are according to official Spanish government data.7 PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

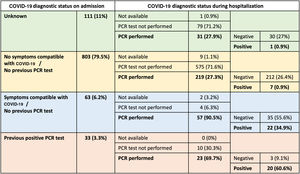

During the COVID-19 outbreak, only 33 patients (3.3%) had confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis at admission; during admission, COVID-19 was diagnosed in 30 additional patients (3.0%), giving a total of 63 patients (6.3%) diagnosed with COVID-19. The COVID-19 diagnostic path in the 2020 cohort is shown in figure 3.

COVID-19 diagnostic path. Patients were categorized on admission according to their COVID-19 status into 4 groups: unknown; no symptoms compatible with COVID-19 and no previous polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test; symptoms compatible with COVID-19 but no previous PCR test; and previous positive PCR test. Although a PCR assay needs to be performed at admission in all patients, it should be noted that PCR was not available in many facilities at the beginning of the pandemic, when this study was carried out.

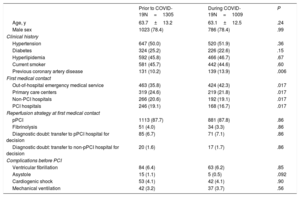

Patients’ baseline clinical characteristics are shown in table 1. With the exception of previous coronary artery disease (more frequent in the COVID-19 cohort), the clinical characteristics were not different between the groups. The mode of presentation significantly differed between groups: during COVID-19, patients more frequently arrived at the hospital via the out-of-hospital emergency medical service and, once at the pPCI hospital, were more frequently admitted directly to the catheterization laboratory.

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients with confirmed diagnosis of STEMI

| Prior to COVID-19N=1305 | During COVID-19N=1009 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.7±13.2 | 63.1±12.5 | .24 |

| Male sex | 1023 (78.4) | 786 (78.4) | .99 |

| Clinical history | |||

| Hypertension | 647 (50.0) | 520 (51.9) | .36 |

| Diabetes | 324 (25.2) | 226 (22.6) | .15 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 592 (45.8) | 466 (46.7) | .67 |

| Current smoker | 581 (45.7) | 442 (44.6) | .60 |

| Previous coronary artery disease | 131 (10.2) | 139 (13.9) | .006 |

| First medical contact | |||

| Out-of-hospital emergency medical service | 463 (35.8) | 424 (42.3) | .017 |

| Primary care centers | 319 (24.6) | 219 (21.8) | .017 |

| Non-PCI hospitals | 266 (20.6) | 192 (19.1) | .017 |

| PCI hospitals | 246 (19.1) | 168 (16.7) | .017 |

| Reperfusion strategy at first medical contact | |||

| pPCI | 1113 (87.7) | 881 (87.8) | .86 |

| Fibrinolysis | 51 (4.0) | 34 (3.3) | .86 |

| Diagnostic doubt: transfer to pPCI hospital for decision | 85 (6.7) | 71 (7.1) | .86 |

| Diagnostic doubt: transfer to non-pPCI hospital for decision | 20 (1.6) | 17 (1.7) | .86 |

| Complications before PCI | |||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 84 (6.4) | 63 (6.2) | .85 |

| Asystole | 15 (1.1) | 5 (0.5) | .092 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 53 (4.1) | 42 (4.1) | .90 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 42 (3.2) | 37 (3.7) | .56 |

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Values are reported as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Angiographic characteristics and the treatment performed are shown in table 2. Radial access was more frequent during COVID-19 and, although there were no differences in the initial and final TIMI flows, there was an increase in mechanical thrombectomy and IIb/IIIa inhibitor administration. There was no difference in the reperfusion strategy after coronary angiography, with up to 94% of patients treated with pPCI in both cohorts and with less than 2% of patients not undergoing any percutaneous coronary intervention.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics of patients with confirmed diagnosis of STEMI

| Prior to COVID-19N=1305 | During COVID-19N=1009 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of patient reception at pPCI hospital | |||

| Direct to catheterization laboratory | 679 (57.3) | 658 (66.0) | <.001 |

| Emergency department | 398 (33.6) | 258 (25.9) | <.001 |

| Critical care unit | 49 (4.1) | 40 (4.0) | <.001 |

| Coronary critical care unit | 45 (3.8) | 25 (2.5) | <.001 |

| Previously admitted to hospital | 14 (1.2) | 14 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Killip class at catheterization laboratory arrival | |||

| I | 1024 (81.0) | 821 (82.4) | .86 |

| II | 115 (9.1) | 83 (8.3) | .86 |

| III | 34 (2.7) | 25 (2.5) | .86 |

| IV | 91 (7.2) | 67 (6.7) | .86 |

| Coronary artery disease extent | |||

| 1-vessel disease | 789 (63.1) | 597 (60.1) | .003 |

| 2-vessel disease | 301 (24.1) | 296 (29.8) | .003 |

| 3-vessel disease | 161 (12.9) | 100 (10.1) | .003 |

| Radial access | 1087 (88.7) | 910 (91.4) | .036 |

| Location of culprit vessel | |||

| Left main coronary artery | 16 (1.2) | 15 (1.5) | .59 |

| Left anterior descending | 542 (41.5) | 454 (45.0) | .095 |

| Left circumflex | 198 (15.1) | 150 (14.9) | .84 |

| Right coronary artery | 476 (36.5) | 388 (38.5) | .33 |

| Bypass graft | 9 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | .55 |

| Initial TIMI flow | |||

| 0 | 847 (68.9) | 724 (72.2) | .18 |

| 1 | 114 (9.3) | 75 (7.5) | .18 |

| 2 | 116 (9.4) | 99 (9.9) | .18 |

| 3 | 153 (12.4) | 105 (10.5) | .18 |

| Final TIMI flow | |||

| 0 | 22 (1.8) | 17 (1.7) | .95 |

| 1 | 15 (1.2) | 11 (1.1) | .95 |

| 2 | 48 (3.9) | 43 (4.3) | .95 |

| 3 | 1152 (93.1) | 925 (92.9) | .95 |

| PCI characteristics | |||

| IIb/IIIa inhibitor administration | 112 (8.6) | 150 (14.9) | <.001 |

| Mechanical thrombectomy | 337 (25.8) | 356 (35.3) | <.001 |

| Balloon angioplasty | 428 (32.8) | 361 (35.8) | .13 |

| Bare-metal stent implantation | 97 (7.4) | 24 (2.4) | <.001 |

| Drug-eluting stent implantation | 1066 (81.7) | 887 (87.9) | <.001 |

| Decision after coronary angiography | |||

| pPCI | 1209 (93.9) | 943 (94.7) | .74 |

| Rescue PCI | 29 (2.3) | 23 (2.3) | .74 |

| Routine early PCI after fibrinolysis | 24 (1.9) | 14 (1.4) | .74 |

| Coronary angiography without PCI | 26 (2.0) | 16 (1.6) | .74 |

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Values are reported as No. (%).

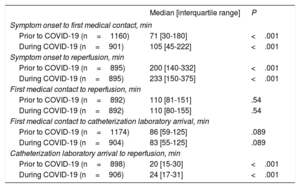

During the COVID-19 outbreak, there was an increase in both time from symptom onset to first medical contact (105 [45-222] vs 71 [30-180] minutes, P <.001) and time from symptom onset to reperfusion (233 [150-375] vs 200 [140-332] minutes, P <.001). In contrast, no differences were observed in the time from first medical contact to reperfusion (110 [80-155] minutes vs 110 [81-151] minutes, P=.54). Five different time intervals between symptom onset and reperfusion are shown in table 3 and figure 4.

Time intervals between symptom onset and reperfusion

| Median [interquartile range] | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptom onset to first medical contact, min | ||

| Prior to COVID-19 (n=1160) | 71 [30-180] | <.001 |

| During COVID-19 (n=901) | 105 [45-222] | <.001 |

| Symptom onset to reperfusion, min | ||

| Prior to COVID-19 (n=895) | 200 [140-332] | <.001 |

| During COVID-19 (n=895) | 233 [150-375] | <.001 |

| First medical contact to reperfusion, min | ||

| Prior to COVID-19 (n=892) | 110 [81-151] | .54 |

| During COVID-19 (n=892) | 110 [80-155] | .54 |

| First medical contact to catheterization laboratory arrival, min | ||

| Prior to COVID-19 (n=1174) | 86 [59-125] | .089 |

| During COVID-19 (n=904) | 83 [55-125] | .089 |

| Catheterization laboratory arrival to reperfusion, min | ||

| Prior to COVID-19 (n=898) | 20 [15-30] | <.001 |

| During COVID-19 (n=906) | 24 [17-31] | <.001 |

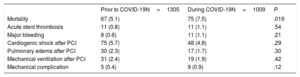

Differences in in-hospital outcomes between the 2 cohorts are shown in table 4. All-cause mortality during COVID-19 was 7.5% vs 5.1% in the prior to COVID-19 group (unadjusted OR, 1.50; 95%CI, 1.07-2.11; P <.001). This association remained consistent after adjustment for age, sex, Killip class, and time from symptom onset to reperfusion (OR, 1.88; 95%CI, 1.12-3.14; P=.017), but it was attenuated after additional adjustment for confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis (OR, 1.56; 95%CI, 0.91-2.67; P=.108).

In-hospital outcomes of patients with confirmed diagnosis of STEMI

| Prior to COVID-19N=1305 | During COVID-19N=1009 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 67 (5.1) | 75 (7.5) | .019 |

| Acute stent thrombosis | 11 (0.8) | 11 (1.1) | .54 |

| Major bleeding | 8 (0.6) | 11 (1.1) | .21 |

| Cardiogenic shock after PCI | 75 (5.7) | 48 (4.8) | .29 |

| Pulmonary edema after PCI | 30 (2.3) | 17 (1.7) | .30 |

| Mechanical ventilation after PCI | 31 (2.4) | 19 (1.9) | .42 |

| Mechanical complication | 5 (0.4) | 9 (0.9) | .12 |

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Values are reported as No. (%).

The robustness of our findings was tested through 2 sensitivity analyses. By excluding COVID-19 patients from the main analyses, we removed their potential contribution to the increase in outcomes and confirmed that the excess mortality was partly explained by COVID-19 itself: the unadjusted OR (95%CI) for patients in 2020 was 1.28 (0.77-1.83) (P=.173), which remained nonsignificant after adjustment for confounding: 1.56 (0.90-2.68) (P=.11). By using random effects models, we allowed for some random heterogeneity across hospitals and obtained similar statistical significance (P=.044) for the association between in-hospital mortality and patients recruited during the COVID-19 outbreak vs those recruited 1 year before: patients with STEMI during the COVID-19 outbreak were at higher risk of in-hospital mortality after adjustment for confounding (P=.033), but this significant association disappeared when COVID-19 status was introduced into the model (P=.203), suggesting that COVID-19 was the driver of the increase in in-hospital mortality between cohorts.

DISCUSSIONIn our study, we evaluated the influence of the COVID-19 outbreak on the management of STEMI patients attended in specific care networks nationwide in Spain, one of the countries most affected by the current pandemic. We compared data from a national registry establishing 2 different 30-day cohorts of patients: prior to the COVID-19 outbreak (from April 1 to April 30, 2019) and during the outbreak (from March 16 to April 14, 2020).

Fewer STEMI patients and longer delays to reperfusionA previous report from our group revealed a 40% decrease in patients treated for STEMI during the first week of the current outbreak.3 Similarly, an American study revealed an estimated 38% reduction in STEMI-related catheterization laboratory activations in 9 high-volume centers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.4 Our results confirm a consistent decrease in the number of STEMI patients treated (in up to 87% of centers), albeit of a lower magnitude (22.7%) than initially believed.3 In addition, there was a significant decrease in the number of patients managed in STEMI networks who ultimately received a diagnosis other than STEMI, reinforcing the belief that patients avoided hospitals. Furthermore, patients had longer delays to reperfusion, largely due to later consultation of the health system because we found no differences in the time from first medical contact to reperfusion. Ischemic time duration is a major determinant of infarct size in patients with STEMI, and prompt recognition and early management of acute STEMI is critical in reducing morbidity and mortality.10–12 Interestingly, the COVID-19 cohort showed a higher prevalence of previous coronary artery disease and more multivessel disease, suggesting that patients with a history of ischemic heart disease may have been less reluctant to go to the hospital. Despite the logistical difficulties caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, we did not detect an increase in the time from first medical contact to reperfusion, which indicates a good adaptation of STEMI networks to the current crisis. On the contrary, there was a longer time from catheterization laboratory arrival to reperfusion, probably due to time spent on the protective measures required for the procedures.13

Potential behavioral explanations for these results would be a combination of avoidance of medical care due to social distancing and concerns about contracting COVID-19 in hospitals. The ongoing outbreak has received massive news coverage, with particular emphasis on the most common forms of infection and places where SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily. Fear is a well-known determinant of medical care avoidance14 and hospital avoidance behaviors have been linked to pandemics.15

Reperfusion strategies and angiographic findings in STEMI during the COVID-19 outbreakVarious scientific societies have developed recommendations on the reperfusion strategy during the COVID-19 outbreak, with advice that may be conflicting, depending on the conditions in each country. In China, the Peking Union Medical College Hospital recommend thrombolysis as first-line treatment and only recommend coronary intervention after COVID-19 is ruled out, even in patients with a thrombolytic contraindication.16 The American College of Cardiology Interventional Council and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions state that fibrinolysis can be considered for relatively stable STEMI patients with active COVID-19 to prevent staff exposure.17 In Spain, there have been no changes to the reperfusion strategy, with more than 98% of STEMIs treated with pPCI and no increase in the use of thrombolysis, in accordance with Spanish Interventional Cardiology Association recommendations on STEMI management during the COVID-19 outbreak.18

Two recently published short series of patients with COVID-19 who had ST-segment elevation showed a high prevalence of nonobstructive disease.19,20 Overall, we did not find an increase in the number of patients without obstructive lesions. This could be a) because we analyzed only patients with confirmed STEMI diagnosis and thus excluded other causes of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries, such as myocarditis, takotsubo syndrome, non-STEMI, and pulmonary embolism, which represented about 10% of patients in our series; or b) because previously published data probably concerned nonconsecutive and highly selected patients.

Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on STEMI-related mortalityA particularly relevant finding of our study is a disturbing elevation in in-hospital mortality during the COVID-19 outbreak. This increase remained consistent after adjustment for age, sex, Killip class, and time from symptom onset to reperfusion.

Recent epidemiologic data suggest a significant increase in mortality during this period that cannot be fully explained by COVID-19 patients alone.21 In the current situation, patients avoid going to the emergency services, or defer going, which could explain the increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, as recently described in Italy.22 Although it is difficult to determine the real prevalence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the setting of STEMI, we did not observe an increase in cases of ventricular fibrillation or asystole or in a need for mechanical ventilation prior to the catheterization laboratory in patients with confirmed STEMI. Up to 75% of deaths are estimated to occur before contact with the health system23 and the main way to prevent out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is for patients to seek hospital treatment as soon as symptoms of STEMI appear.24 Therefore, it is possible that an increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest may not be reflected in our study.

Lack of access to reperfusion treatment would also increase subacute STEMI complications, such as heart failure and/or cardiogenic shock, intraventricular thrombus formation and peripheral embolism, and mechanical complications.25 These patients were not included in the present registry because they were not candidates for pPCI but they undoubtedly contribute to STEMI-related excess mortality.

Finally, in the long term, suboptimal revascularization and a larger infarct size will increase complications related to worse ventricular remodeling, such as chronic heart failure and ventricular arrhythmias.26

LimitationsThis study has limitations inherent to the analysis of multicentric observational data. Baseline and follow-up data were assessed at the center-level by each clinician-investigator, without central confirmation, potentially resulting in inaccuracies and misclassifications. Nevertheless, data on interventional cardiology are quite standardized worldwide and the electronic case report form was designed to be intuitively and universally completed by all clinicians. Moreover, we applied a mixed regression model including hospital as a random variable, which considered within- and between-hospital variations over time. In any case, the potential variability among clinicians approximates our findings to those of clinical practice and improves their generalizability. Any potential selection bias was addressed by adjustment of logistic regressions for potential confounders with prognostic implications, although some residual confounding (either measured or unmeasured) might remain after multivariate modeling.

CONCLUSIONSIn conclusion, this nationwide, observational study has revealed a decrease in the number of patients with STEMI managed during the current COVID-19 outbreak, with an increase in time from symptom onset to reperfusion and a significant 2-fold increase in in-hospital mortality. No changes in reperfusion strategy were detected. Concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection in STEMI patients was infrequent but had an impact on in-hospital mortality.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTA. Pérez de Prado has received personal fees from iVascular, Boston Scientific, Terumo, B. Braun, and Abbott Laboratories. Á. Cequier has received personal fees from Ferrer International, Terumo, AstraZeneca, and Biotronik. All other authors have reported that they have no relationship relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

- -

Some preliminary reports have highlighted a decrease in the number of STEMI patients attending hospitals during the current COVID-19 outbreak.

- -

There is little information on the influence of the COVID-19 outbreak on STEMI care and outcomes.

- -

We found a significant decrease in the number of patients with STEMI managed in specific care networks in Spain during COVID-19.

- -

When compared with a cohort from the previous year, patients managed during the COVID-19 outbreak had a longer ischemia time and increased mortality, although there were no differences in the reperfusion strategy.

APPENDIX. WORKING GROUP ON THE INFARCT CODE OF THE SPANISH INTERVENTIONAL CARDIOLOGY ASSOCIATION INVESTIGATORS

Key personnel and participating study sites:

Manuel Villa, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío; Rafael Ruíz-Salmerón, Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena; Francisco Molano, Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme; Carlos Sánchez, Hospital Universitario General de Málaga; Erika Muñoz-García, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria; Luis Íñigo, Hospital Costa del Sol; Juan Herrador, Hospital Universitario de Jaén; Antonio Gómez-Menchero, Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez; Eduardo Molina, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves; Juan Caballero, Hospital Universitario San Cecilio; Soledad Ojeda, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía; Mérida Cárdenas, Hospital Punta de Europa; Livia Gheorghe, Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar; Jesús Oneto, Hospital Universitario de Jerez de la Frontera; Francisco Morales, Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real; Félix Valencia, Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas; José Ramón Ruiz, Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa; José Antonio Diarte, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet; Pablo Avanzas, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias; Juan Rondán, Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes; Vicente Peral, Hospital Universitari Son Espases; Lucía Vera Pernasetti, Policlínica Nuestra Señora del Rosario; Julio Hernández, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria; Francisco Bosa, Hospital Universitario de Canarias; Pedro Luis Martín Lorenzo, Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín; Francisco Jiménez, Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria; José M. de la Torre Hernández, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla de Santander; Jesús Jiménez-Mazuecos, Hospital General Universitario de Albacete; Fernando Lozano, Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real; José Moreu, Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo; Enrique Novo, Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara; Javier Robles, Hospital Universitario de Burgos; Javier Martín Moreiras, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca; Felipe Fernández-Vázquez, Hospital de León; Ignacio J. Amat-Santos, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, CIBERCV; Joan Antoni Gómez-Hospital, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge; Joan García-Picart, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Bruno García del Blanco, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Ander Regueiro, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona; Xavier Carrillo-Suárez, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol; Helena Tizón, Hospital del Mar; Mohsen Mohandes, Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII; Juan Casanova, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova; Víctor Agudelo-Montañez, Hospital Universitari de Girona Josep Trueta; Juan Francisco Muñoz, Hospital Universitari Mútua de Tarrassa; Juan Franco, Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz; Roberto del Castillo, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón; Pablo Salinas, Hospital Clínico San Carlos y Hospital Príncipe de Asturias; Jaime Elízaga, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón; Fernando Sarnago, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre; Santiago Jiménez-Valero, Hospital Universitario La Paz; Fernando Rivero, Hospital Universitario de La Princesa; Juan Francisco Oteo, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda; Eduardo Alegría-Barrero, Hospital Univesitario de Torrejón-Universidad Francisco de Vitoria; Ángel Sánchez-Recalde, Hospital Ramón y Cajal; Valeriano Ruiz, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra; Eduardo Pinar, Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca; Luciano Consuegra-Sánchez, Hospital Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena; Ana Planas, Hospital General Universitario de Castellón; Bernabé López Ledesma, Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe; Alberto Berenguer, Hospital General Universitario de Valencia; Agustín Fernández-Cisnal, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia; Pablo Aguar, Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset; Francisco Pomar, Hospital Universitario de la Ribera; Miguel Jerez, Hospital de Manises; Francisco Torres, Hospitales de Torrevieja-Elche-Vinalopó; Ricardo García, Hospital General Universitario de Elche; Araceli Frutos, Hospital General Universitario de San Juan de Alicante; Juan Miguel Ruiz Nodar, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante; Koldobika García, Hospital Universitario de Cruces; Roberto Sáez, Hospital de Basurto; Alfonso Torres, Hospital Universitario Araba; Miren Tellería, Hospital Universitario Donostia; Mario Sadaba, Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo; José Ramón López Mínguez, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz; Juan Carlos Rama Merchán, Hospital de Mérida; Javier Portales, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Cáceres; Ramiro Trillo Hospital Clínico Universitario Santiago de Compostela; Guillermo Aldama, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña; Saleta Fernández, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo; Melisa Santás, Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti; and María Pilar Portero Pérez, Hospital San Pedro de Logroño.