Heart failure (HF) is a major health care problem in Spain. Epidemiological data from hospitalized patients are scarce and the association between hospital characteristics and patient outcomes is largely unknown. The aim of this study was to identify the factors associated with in-hospital mortality and readmissions and to analyze the relationship between hospital characteristics and outcomes.

MethodsA retrospective analysis of discharges with HF as the principal diagnosis at hospitals of the Spanish National Health System in 2012 was performed using the Minimum Basic Data Set. We calculated risk-standardized mortality rates (RSMR) at the index episode and risk-standardized cardiac diseases readmissions rates (RSRR) and in-hospital mortality at 30 days and 1 year after discharge by using a multivariate mixed model.

ResultsWe included 77 652 HF patients. Mean age was 79.2±9.9 years and 55.3% were women. In-hospital mortality during the index episode was 9.2%, rising to 14.5% throughout the year of follow-up. The 1-year cardiovascular readmissions rate was 32.6%. RSMR were lower among patients discharged from high-volume hospitals (> 340 HF discharges) (in-hospital RSMR, 10.3±5.6%; 8.6±2.2%); P <.001). High-volume hospitals had higher 1-year RSRR (32.3±3.7%; 33.7±4.5%; P=.006). The availability of a cardiology department at the hospital was associated with better outcomes (in-hospital RSMR, 9.9±3.8%; 9.2±2.4%; P <.001).

ConclusionsHigh-volume hospitals and the availability of a cardiology department were associated with lower in-hospital mortality.

Keywords

As in many other European countries, heart failure (HF) is a major health care problem in Spain. Its prevalence ranges from 4.7% to 6.8%.1,2 Although some authors have described a gradual decrease in mortality among Spanish HF patients over the last 2 decades,3 recent regional series point to persistent high mortality and readmission rates.4–6 There is no doubt about the relevance of clinical factors in HF prognosis. However, there are relevant differences in hospital performance.7

Current HF hospitalization data on well-defined Spanish populations from appropriately designed studies are scarce. An in-depth understanding, based on information directly obtained from a real-world population, may be helpful to adopt the best approach to address the problem. For this purpose, the Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS) of the Spanish National Health System (SNHS) supplied extensive demographic and clinical information related to any HF hospitalization.8

Accordingly, this study was designed to: a) describe the current demographics and clinical profile of hospitalized patients with HF in Spain; b) identify the risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality and hospital readmission, and c) to analyze the relationship between hospital characteristics and patient outcomes.

MethodsStudy populationWe conducted a retrospective longitudinal study using information provided by the MBDS of the SNHS, which is represented by the full set of public health services in Spain. All episodes with a principal discharge diagnosis of HF from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2012 were included. Principal diagnoses of HF was identified by the International Classification Diseases Ninth Review, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93 and 428.*.9 Patients were identified by their health card code, encrypted by a random number to ensure their privacy. The first discharge for HF in 2012 of a given patient was typified as the “index episode”.

To improve the consistency and quality of the data, we adapted the models developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).9,10 Thus, we excluded patients aged <35 and> 94 years, those who were discharged alive within 1 day after admission, and those in which the reason for discharge was not clear or discharge was taken against medical advice. We also excluded discharges to other hospitals to avoid duplicates and false readmissions in the same episode.

Risk factors for in-hospital mortality and readmissions were selected according to the CMS.9 All patients were followed up for 1 year after hospital discharge.

In-hospital mortality and cardiac diseases readmissionsThe outcome variables were in-hospital mortality at the index episode and in-hospital mortality and readmissions for cardiac diseases readmission at 30-days and 1-year after discharge. For the readmission estimates, in-hospital deaths in the index episode and elective readmissions were excluded. Only the first readmission in the considered period (30 days, 1 year) was taken into account if there were several readmissions. Only readmissions related to “cardiac diseases” as the principal episode were considered. The cardiac diseases considered were rheumatic heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 390.*-398.*), hypertensive heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 401.*-405.*), ischemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 410.*-414.*), diseases of pulmonary circulation (ICD-9-CM codes 415.*-417.*), other forms of heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 420.*-429.*), and aortic aneurysm and dissection (ICD-9-CM codes 441.01, 441.1, 441.2, 444.1).

Hospital characteristicsHospital characteristics including hospital volume, as well as the availability of cardiologic resources (cardiac surgery, on-site catheterization laboratory, and heart transplant program) were taken into account. Data on structural hospital characteristics were obtained from RECALCAR.11

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range], and categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Risk-standardized mortality and readmission rates (RSMR and RSRR respectively) were calculated using a multilevel logistic regression model developed by the Medicare and Medicaid Services,9,10 adapted to the database structure of the MBDS of the SNHS, in which hospitals were modeled as random intercept. MBDS secondary diagnoses were grouped in condition categories according to Pope et al.,12 updated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The final model was built by means of the backward elimination technique. The adjustment coefficients and the factors ultimately included in the in-hospital mortality and readmission models were derived from our own data. The significance levels for selection and elimination were P <.05 and P ≥ .10, respectively.

In addition to the patients’ demographic and clinical variables, multilevel models of risk adjustment take into consideration specific hospital-level factors.13–15 The RSMR and RSRR were calculated as the ratio of the number of in-hospital deaths and readmissions predicted on the basis of the hospital's performance with its observed casemix to the number of in-hospital deaths and readmissions expected on the basis of the all-hospitals performance with that hospital's casemix, multiplied by the all-hospitals unadjusted in-hospital mortality and readmissions rates. This approach allowed a comparison of a particular hospital's performance given its casemix to an average hospital's performance with the same casemix.9

The discrimination of the model was assessed with receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. Multilevel models were used to obtain RSMR and RSRR to compare outcomes among different hospitals. RSRR were not adjusted for death as a competing event because the MBDS of the MBDS does not contain information about out-of-hospital deaths. Data on hospital characteristics were determined by ANOVA or the Student t test, when appropriate.

To discriminate between high- and low-volume centers, a K-means clustering algorithm was used, excluding hospitals with <25 cases of HF (26 exclusions), with the aim of obtaining the maximal intragroup and the minimal intergroup density. The mathematical model was developed with two thirds of the dataset and validated with the remaining one third. The association between volume and RSMR or RSRR was tested with the Pearson correlation coefficient and linear regression models.

All tests were 2-sided, and differences were considered statistically significant at P <.05. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were also obtained. The statistical analysis was performed with Stata software version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) and SPSS version 20. The present study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was exempt from additional review by the ethics investigation committee because all data were de-identified.

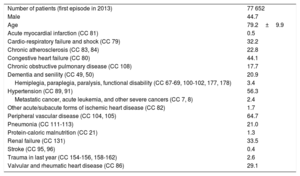

ResultsBaseline characteristicsDuring the year 2012, 86177 index episodes were identified: 8525 (9.9%) were excluded and 77652 patients were finally included in the study. The main causes of exclusion (categories not mutually exclusive) were: same or next day discharges, and discharged alive (35%), age younger than 35 or older than 94 years (32%), and transferred to another hospital (26%).

The mean age was 79.2 (9.9) years and 55.3% were women. The most common comorbidities were peripheral artery disease (64.7%), hypertension (56.3%), chronic kidney disease (33.5%), valvular heart disease (29.1%), dementia (20.9%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17.7%) (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of heart failure patients at the index episode

| Number of patients (first episode in 2013) | 77 652 |

| Male | 44.7 |

| Age | 79.2±9.9 |

| Acute myocardial infarction (CC 81) | 0.5 |

| Cardio-respiratory failure and shock (CC 79) | 32.2 |

| Chronic atherosclerosis (CC 83, 84) | 22.8 |

| Congestive heart failure (CC 80) | 44.1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (CC 108) | 17.7 |

| Dementia and senility (CC 49, 50) | 20.9 |

| Hemiplegia, paraplegia, paralysis, functional disability (CC 67-69, 100-102, 177, 178) | 3.4 |

| Hypertension (CC 89, 91) | 56.3 |

| Metastatic cancer, acute leukemia, and other severe cancers (CC 7, 8) | 2.4 |

| Other acute/subacute forms of ischemic heart disease (CC 82) | 1.7 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (CC 104, 105) | 64.7 |

| Pneumonia (CC 111-113) | 21.0 |

| Protein-caloric malnutrition (CC 21) | 1.3 |

| Renal failure (CC 131) | 33.5 |

| Stroke (CC 95, 96) | 0.4 |

| Trauma in last year (CC 154-156, 158-162) | 2.6 |

| Valvular and rheumatic heart disease (CC 86) | 29.1 |

CC, condition categories.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or percentage.

The crude in-hospital mortality rate during the index episode was 9.2%, rising to 14.5% (cumulative rate) throughout the year of follow-up (10.4% at 1 month and 11.8% at 3 months).

Throughout the year of follow-up, 37 247 episodes of cardiac hospitalization were registered, corresponding to 23 661 patients. The overall rate of cardiac readmission reached 32.6% (9.7% during the first month after hospital discharge). The main cause of hospital readmission was decompensated HF (62.8%), followed by ischemic heart disease episodes (6.8%).

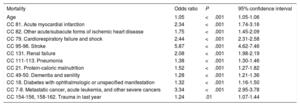

Multilevel regression analysis identified the main risk factors for in-hospital mortality at the index episode (Table 2) and for 1-year in-hospital mortality and hospital readmissions (). Stroke, metastatic cancer, cardio-respiratory failure and shock and acute myocardial infarction were found to have the strongest association with in-hospital mortality (Table 2), and also with in-hospital mortality at 1-year, whereas valvular heart disease, diabetes mellitus and myocardial revascularization were consistently related to increased 1-year readmission rates. Renal failure was strongly associated with both in-hospital mortality and hospital readmission (). The area under the ROC curve for in-hospital mortality at the index episode was 0.745 (Figure 1), and was 0.735 and 0.706 at 30 days and 1-year, respectively (). The median OR for in-hospital mortality at the index episode was 1.49, denoting high interhospital variability. The area under the ROC curve for identifying patients with cardiovascular hospital readmission within 30 days and at 1 year was 0.598 and 0.612, respectively.

Risk factors for in-hospital mortality at the index episode

| Mortality | Odds ratio | P | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.05 | <.001 | 1.05-1.06 |

| CC 81. Acute myocardial infarction | 2.34 | <.001 | 1.74-3.16 |

| CC 82. Other acute/subacute forms of ischemic heart disease | 1.75 | <.001 | 1.45-2.09 |

| CC 79. Cardiorespiratory failure and shock | 2.44 | <.001 | 2.31-2.58 |

| CC 95-96. Stroke | 5.87 | <.001 | 4.62-7.46 |

| CC 131. Renal failure | 2.08 | <.001 | 1.98-2.19 |

| CC 111-113. Pneumonia | 1.38 | <.001 | 1.30-1.46 |

| CC 21. Protein-caloric malnutrition | 1.52 | <.001 | 1.27-1.82 |

| CC 49-50. Dementia and senility | 1.28 | <.001 | 1.21-1.36 |

| CC 18. Diabetes with ophthalmologic or unspecified manifestation | 1.32 | <.001 | 1.16-1.50 |

| CC 7-8. Metastatic cancer, acute leukemia, and other severe cancers | 3.34 | <.001 | 2.95-3.78 |

| CC 154-156, 158-162. Trauma in last year | 1.24 | .01 | 1.07-1.44 |

CC, condition categories.

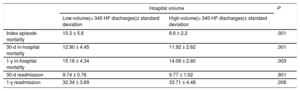

Information on the number of HF discharges at each hospital was analyzed to classify centers into 2 categories (high- and low-volume hospitals). The cutoff point was set at 340 HF discharges per hospital during 2012. Sixty-four per cent of the patients (49 765) and 35.34% of the hospitals (94) were classified as being in the high-volume category.

RSMR were lower among patients admitted to high-volume hospitals (–16.5% at the index episode,–7.6% at 30 days and–7.1% at 1 year) (Figure 2, Table 3); conversely, high-volume hospitals had higher 1-year cardiac readmission rates (4.2%), (Table 3).

Hospital risk standardized in-hospital mortality and cardiac readmission rates according to hospital volume

| Hospital volume | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-volume(< 340 HF discharges)± standard deviation | High-volume(> 340 HF discharges)± standard deviation | ||

| Index episode mortality | 10.3 ± 5.6 | 8.6 ± 2.2 | .001 |

| 30-d in-hospital mortality | 12.90 ± 4.45 | 11.92 ± 2.62 | .001 |

| 1-y in-hospital mortality | 15.16 ± 4.34 | 14.08 ± 2.80 | .003 |

| 30-d readmission | 9.74 ± 0.76 | 9.77 ± 1.02 | .801 |

| 1-y readmission | 32.34 ± 3.69 | 33.71 ± 4.48 | .006 |

HF, heart failure.

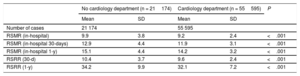

Regarding hospital cardiologic resources, 98 (33.6%) out of the 292 participating hospitals had a cardiac catheterization laboratory. Cardiac surgery was available in 46 centers (15.7%); 15 of them had a heart transplant program. When we analyzed the impact of these resources on outcomes (), we found no association that was statistically significant and independent from volume between their availability and in-hospital mortality (at the index episode, 30 days and 1 year) and 30-day readmissions (P> .05). However, the availability of a structured cardiology department was associated with better outcomes than hospitals without a cardiology department (Table 4).

Outcomes associated with the availability of a structured cardiology department

| No cardiology department (n = 21174) | Cardiology department (n = 55595) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Number of cases | 21 174 | 55 595 | |||

| RSMR (in-hospital) | 9.9 | 3.8 | 9.2 | 2.4 | <.001 |

| RSMR (in-hospital 30-days) | 12.9 | 4.4 | 11.9 | 3.1 | <.001 |

| RSMR (in-hospital 1-y) | 15.1 | 4.4 | 14.2 | 3.2 | <.001 |

| RSRR (30-d) | 10.4 | 3.7 | 9.6 | 2.4 | <.001 |

| RSRR (1-y) | 34.2 | 9.9 | 32.1 | 7.2 | <.001 |

RSMR, risk-standardized mortality rates; RSRR, risk-standardized readmission rates; SD, standard deviation.

This study describes the current demographics, clinical characteristics and outcomes of acute decompensated HF patients in Spain. The patients were old (the mean age was 79 years) and had a high burden of comorbidity. In-hospital mortality at the index episode was high (9.2%). The most important risk factors for in-hospital mortality and at 1-year were stroke, metastatic cancer, cardiorespiratory failure and shock, and acute myocardial infarction.

One-year in-hospital mortality and readmission rates in our series were high (14.5% and 32.6%, respectively). Recently published HF registries report higher 1-year mortality and readmission rates.16,17 An explanation for the lower 1-year morbidity and mortality rates in this study is that the MBDS of the SNHS does not contain information about out-of-hospital deaths and noncardiac readmissions were not available and were therefore not analyzed. The ESC-HF Pilot Study prospectively analyzed 5118 HF patients (37% admitted for acute HF) from 136 Cardiology centers in 12 European countries. Among the hospitalized population, the 1-year all-cause mortality and readmission rates were 17.4% and 43.9%, respectively.17 In addition, the ESC-HF-LT collected data from 12 440 patients (40.5% of them hospitalized with acute decompensated HF) in 21 European and/or Mediterranean countries.17 The 1-year all-cause mortality rate ranged from 21.6% to 36.5% between distinct regions. A recent population-based study in a Spanish region found 31% 1-year readmissions due to cardiovascular causes, a figure remarkably similar to our finding (32.6%).6

Hospital readmissions are frequent in HF patients and are associated with increased mortality,6,18 and tend to remain unchanged over time.19 In this series, the main cause of hospital readmission was a decompensated HF episode (62.8%). Readmissions may be associated with health care management in the hospital20 and at the community,21,22 in addition to comorbidities, having poor predictive models.23 In this study, the main risk factors associated with 1-year in-hospital mortality were the same as in-hospital mortality at the index episode, whereas valvular heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and myocardial revascularization were clearly related to increased 1-year readmission rates. Renal failure was strongly associated with both in-hospital mortality and hospital readmission. These findings perfectly match those recently published by Farré et al.4 regarding 88195 prevalent HF cases in Spain. Nonetheless, the prognostic burden associated with comorbidities generally depends on the study population.24,25

We found that patients hospitalized for HF had lower in-hospital mortality if they were admitted to a high-volume hospital. A greater dispersion of data were observed in low-volume hospitals (Figure 2). Ross et al. also found an association between hospital volume and 30-day mortality in 1 324 287 HF patients with a volume threshold (500 patients HF at year) above which an increased hospital volume was no longer significantly associated with reduced mortality.26 We have also found that high-volume hospitals had higher 1-year readmission rates. These results are consistent with previously published data.27 Kumbhani et al.28 analyzed the association between HF volume with outcomes in patients included in the GWTG-HF (Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure) registry. They found a weak association between higher volumes and lower 6-month mortality and all-cause readmissions, and the adherence to HF process measures was lower among small-volume hospitals, but the upper quartile of HF volume in their series was only 123 HF cases in a year.28

We did not find a statistically significant association that was independent from volume between on-site cardiac or heart transplant surgery and outcomes. However, we found an association between the availability of a structured cardiology department with better outcomes (Table 4). We cannot rule out the influence on patient mortality of other hospital characteristics associated with high-volume hospitals (eg, 24-hour availability of a cardiologist, existence of a HF unit, and nurses and physicians specialized in HF management). To deepen the knowledge of the associations between hospital characteristics other than volume and health outcomes, appropriate studies covering individual factors and specific characteristics of the overall HF hospital organization need to be performed.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. Although it is a retrospective analysis based on MBDS data, the use of administrative information has proven to be valid to estimate outcomes in health services, compared with medical records.29,30 The reliability of this kind of study enables the public comparison of different hospitals.7 The use of the same personal identifiers for recording hospital discharges and in-hospital mortality facilitated the data gathering process during follow-up. Discriminative accuracy for the adjustment model of hospital readmissions in our study was very poor (0.598 and 0.612), but was similar to the CMS model7 and to other population studies on hospital readmissions, whose areas under ROC curve were between 0.55 and 0.65,31,32 their use being less inaccurate than the unadjusted crude readmission rates.

In contrast with the methodology used by the CMS,9,10 we could not analyze all-cause readmissions because the Ministry of Health only provided data on cardiac diseases discharges. In addition, information related to those patients who died outside the hospital could not be obtained. However, based on our 1-year mortality rate, it can be assumed that proportionally there are few patients hospitalized for HF (index episode) who die outside the hospital in the year following discharge, either due to sudden death or other causes. The 1-year in-hospital mortality rate of our series (14.4%) is very similar to the figure reported for 1-year mortality for cardiovascular causes of the ESC-HF Pilot Registry for patients discharged from hospitals in the southern region of Europe (16.8%, with out-of-hospital deaths being included), taking into consideration that our study does not track cerebrovascular deaths.33 Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the real HF mortality rate must be somewhat higher than the figure we report.

Another limitation is that there were unidentifiable confounding factors in the adjustment models that could have a significant impact. The secondary diagnoses considered as risk-adjustment variables corresponded to conditions that were present on admission or to complications that might occasionally reflect inadequate treatment. RSRR were not adjusted for death as a competing event. However, our method was similar to previously validated models in terms of its predictive capacity.7,31,32

MBDS data misclassification did not allow us to assess mortality or readmissions based on the current classification of HF. Nevertheless, the impact of ejection fraction on HF outcome remains controversial. The latest data show that mortality in patients with HF is similar regardless of ejection fraction.34

ConclusionsOur results highlight the aging and high comorbidity burden of patients admitted to Spanish hospitals for decompensated HF. High volume was related to lower in-hospital mortality. The availability of a structured cardiology department was associated with better outcomes.

FundingThis work was supported by an unconditional grant from the Fundación Interhospitalaria para la Investigación Cardiovascular.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

- –

HF constitutes a major public health concern in western European countries.

- –

Data on its real impact in the general population may be helpful to develop specific programs to prevent mortality and hospital readmission.

- –

The hospital structure analysis reveals that certain features of the health system organization may result in worse outcomes among acute decompensated HF patients.

- –

Further studies should evaluate the impact of the overall HF hospital organization on the outcome of acute decompensated HF.

The authors thank the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality for providing the MBDS, with special gratitude to the General Directorate of Public Health, Quality, and Innovation.