There are scarce data on left atrial (LA) enlargement and electrophysiological features in athletes.

MethodsMulticenter observational study in competitive athletes and controls. LA enlargement was defined as LA volume indexed to body surface area ≥ 34mL/m2. We analyzed its relationship with atrial electrocardiography parameters.

ResultsWe included 356 participants, 308 athletes (mean age: 36.4±11.6 years) and 48 controls (mean age: 49.3±16.1 years). Compared with controls, athletes had a higher mean LA volume index (29.8±8.6 vs 25.6±8.0mL/m2, P=.006) and a higher prevalence of LA enlargement (113 [36.7%] vs 5 [10.4%], P <.001), but there were no relevant differences in P-wave duration (106.3±12.5ms vs 108.2±7.7ms; P=.31), the prevalence of interatrial block (40 [13.0%] vs 4 [8.3%]; P=.36), or morphology-voltage-P-wave duration score (1.8±0.84 vs 1.5±0.8; P=.71). Competitive training was independently associated with LA enlargement (OR, 14.7; 95%CI, 4.7-44.0; P <.001) but not with P-wave duration (OR, 1.02; 95%CI, 0.99-1.04), IAB (OR, 1.4; 95%CI, 0.7-3.1), or with morphology-voltage-P-wave duration score (OR, 1.4; 95%CI, 0.9-2.2).

ConclusionsLA enlargement is common in adult competitive athletes but is not accompanied by a significant modification in electrocardiographic parameters.

Keywords

Physical exercise is beneficial, but if intensive, it can cause potentially deleterious cardiac remodeling.1 The characteristics that define “athlete's heart”2,3 include dilatation of the chambers of the heart.4 Dilatation of the left atrium (LA) in competitive athletes can be considered an adaptive mechanism, which is not secondary to an increase in left ventricular filling pressures or mitral valve disease.5 However, there is a clear association between LA dilatation and an increased rate of cardiovascular events, even in individuals with no supraventricular tachyarrhythmias or valve disease.6,7 Recent studies have analyzed the risks associated with LA dilatation in athletes, principally due to the potential predisposition to atrial fibrillation.8

Echocardiography is the most frequently used method for assessing LA volume,9 and the LA volume indexed to the body surface area (LAVi) has been shown to have prognostic value.10 Previous studies have indicated a poor correlation between electrocardiographic P wave criteria and LA size in the general population.11 The association between LA dilatation and atrial physiology characteristics has not been analyzed in competitive athletes, a group in which the upper limit for normal LA size is unclear.4,5 Our objective was to analyze LA dilatation, P-wave duration, and interatrial block (IAB) in competitive athletes.

METHODSALMUDAINA (In Spanish, Análisis y Lectura de Mediciones Uniformes de Dilatación Auricular Izquierda Notificadas en Atletas; in English, Analysis and Reading of Uniform Measurements of Left Atrial Dilatation Reported in Athletes) is a national retrospective observational study with 9 participating Spanish hospitals. The study period was from January to September 2020. Individuals who met the study participation criteria were those aged ≥ 16 years, who had a digitalized electrocardiogram (ECG) and a transthoracic echocardiogram done on the same day. The exclusion criteria were the following: a) ischemic heart disease, moderate or severe valve disease, left ventricular ejection fraction <50% or known primary cardiomyopathy (hypertrophic, dilated, arrhythmogenic, or noncompaction); b) significant arrhythmias; c) implanted cardiac device; d) no measurable P waves on surface ECG; e) poor transthoracic window; f) chest-wall abnormality or deformity; and g) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Patients were selected if they met the consensus definition of competitive athlete (participation in an individual or team sport that involves regular competition against other athletes, places great importance on excellence and success, and demands regular and generally intensive training)12,13 in a skilled, strength, resistance, or mixed activity, at a national or international level.

The selected controls were individuals not participating in competitive sports (recreational sport was allowed) and not taking part in regular training programs.

A resting 12-lead surface ECG was obtained for each participant in line with established standards (25mm/s and 10mm/50mV), with amplitude filtering of 0.05-150Hz and a 50-Hz filter. The following P-wave parameters were analyzed: a) duration, b) voltage in lead I, and c) MVP (morphology-voltage-P-wave duration) score.14 We analyzed the presence of IAB, whether partial (defined as a P wave duration ≥ 120ms, with positive polarity in the inferior leads) or advanced (P wave duration ≥ 120ms with a biphasic morphology [±] in the inferior leads).15 The MVP score is a risk scale that can help predict de novo atrial fibrillation and is calculated by assigning points according to P-wave morphology in the inferior leads (0-2), its voltage in lead I (0-2), and its duration (0-2).14 The P-wave duration is measured manually in a central laboratory using GeoGebra 4.2 software after amplifying the original size of the ECG by a factor of 20. All measurements were performed by an observer who was blinded to the patients’ clinical and electrocardiographic data and, if there was any uncertainty, a second observer was consulted.

Two-dimensional transthoracic Doppler echocardiograms were analyzed by experienced echocardiogram specialists and acquired in line with the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging for cardiac chamber quantification.9 LA size was quantified at end-systole with the following measurements averaged after 3 consecutive cycles: a) anteroposterior LA diameter (parasternal long-axis view), b) LA area (apical 4-chamber view), and c) LA volume (on apical 2-chamber and 4-chamber views, using the modified biplane method of disc summation). The LA volume was indexed to body surface area to obtain the LAVi. An LAVi ≥ 34mL/m2 was used to define LA dilatation.9,16 If the LAVi could not be calculated, LA area (≥ 20cm2) was used as the criterion to define LA dilatation.9 Right atrial dilatation was defined using area (> 18cm2) or indexed volume (25mL/m2).

Baseline clinical characteristics were recorded for all participants: age weight, height, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, family history of sudden cardiac death, and pharmacological treatment. Blood pressure was measured with automated devices after a 5-minute rest period.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee of the coordinating hospital. Being a strictly observational, descriptive, retrospective study, with no participants subject to an intervention, the ethics committee exempted the requirement for an informed consent form.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are reported as frequency and percentage. Continuous variables are reported as mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range] if they did not follow a normal distribution. The chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical variables and Student t test, Kruskal-Wallis, or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparison of continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the association between competitive training and the presence of LA dilatation and the atrial electrocardiographic indices. All the variables were initially included in the model and then selected using backward stepwise regression. To study the association of LA dilatation with participation in competitive sport, we also performed propensity score adjustment. For this, numerical variables and missing values were recoded to avoid losing sample size. The logistic model for case-control prediction showed good calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow, P=.549) and discrimination (receiver operating characteristics [ROC] area under the curve, 0.891). All statistical tests were based on a 2-tailed hypothesis test. Statistical analysis was performed with the software package SPSS, version 23.0 (IBM, USA).

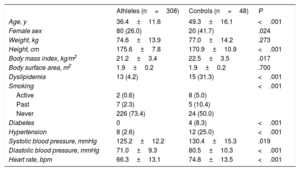

RESULTSThe final population included 356 Caucasian participants: 308 cases and 48 controls. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ baseline characteristics. Compared with controls, the athlete group was younger (36.4±11.6 vs 49.3±16.1 years) and had a lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and lower heart rate. In the competitive athlete group, the most common type of activity was resistance sports (n=221, 71.8%), followed by strength (n=35 [11.4%]) and a combination of both (n=52 [16.9%]).

Baseline clinical characteristics of athletes and controls

| Athletes (n=308) | Controls (n=48) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 36.4±11.6 | 49.3±16.1 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 80 (26.0) | 20 (41.7) | .024 |

| Weight, kg | 74.6±13.9 | 77.0±14.2 | .273 |

| Height, cm | 175.6±7.8 | 170.9±10.9 | <.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21.2±3.4 | 22.5±3.5 | .017 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.9±0.2 | 1.9±0.2 | .700 |

| Dyslipidemia | 13 (4.2) | 15 (31.3) | <.001 |

| Smoking | <.001 | ||

| Active | 2 (0.6) | 8 (5.0) | |

| Past | 7 (2.3) | 5 (10.4) | |

| Never | 226 (73.4) | 24 (50.0) | |

| Diabetes | 0 | 4 (8.3) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 8 (2.6) | 12 (25.0) | <.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 125.2±12.2 | 130.4±15.3 | .019 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 71.0±9.3 | 80.5±10.3 | <.001 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 66.3±13.1 | 74.8±13.5 | <.001 |

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Table 2 summarizes the echocardiographic characteristics of the two groups. Compared with controls, the athletes had a higher LAVi (29.8±8.6 vs 25.6±8.0mL/m2) and higher prevalence of LA dilatation (36.7% vs 10.4%). Interventricular septum thickness, left ventricular volumes, and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion were also higher in athletes than controls.

Echocardiographic data from athletes and controls

| Athletes (n=308) | Controls (n=48) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left atrium | |||

| Anteroposterior diameter, mm | 36.0±4.6 | 34.6±2.6 | .378 |

| Volume, mL | 54.2±18.9 | 36.2±15.2 | .015 |

| LAVi, mL/m2 | 29.8±8.6 | 25.6±8.0 | .006 |

| LA dilatation | 113 (36.7) | 5 (10.4) | <.001 |

| Mild | 98 (31.8) | 5 (10.4) | |

| Moderate | 10 (3.2) | 0 | |

| Severe | 5 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Left ventricle | |||

| IVS, mm | 9.7±1.55 | 8.8±1.6 | .002 |

| PW, mm | 9.6±2.7 | 9.1±6.2 | .526 |

| EDD, mm | 51.6±4.3 | 48.0±5.7 | <.001 |

| ESD, mm | 32.1±4.2 | 27.4±5.5 | <.001 |

| Mass, g | 183.4±48.6 | 175.8±31.1 | .685 |

| Indexed mass, g/m2 | 96.0±22.1 | 88.0±11.3 | <.001 |

| LVEF, % | 68.1±5.1 | 72.9±5.4 | <.001 |

| E wave, cm/s | 90.9±21.0 | 80.3±16.2 | .188 |

| A wave, cm/s | 59.1±19.3 | 54.1±11.9 | .492 |

| E/A ratio | 1.6±0.5 | 1.3±1.0 | .707 |

| DT, ms | 200.8±38.6 | 201.4±41.4 | .965 |

| E/e’ ratio | 5.7±1.5 | 7.5±1.8 | <.001 |

| Transmitral filling pattern | .483 | ||

| Normal | 273 (88.6) | 44 (91.7) | |

| Impaired relaxation | 34 (11.0) | 4 (8.3) | |

| Pseudonormal | 1 (0.3) | 0 | |

| Restrictive | 0 | 0 | |

| Right heart | |||

| TAPSE, mm | 25.9±2.7 | 23.2±3.8 | <.001 |

| Right atrial dilatation | 119 (38.6) | 6 (12.5) | .002 |

| Aorta | |||

| Ascending, mm | 29.43±5.28 | 31.57±4.48 | .060 |

| Aortic arch, mm | 23.01±3.56 | 25.57±3.21 | .075 |

DT, deceleration time; EDD, end-diastolic diameter; ESD, end-systolic diameter; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium; LAVi, left atrial volume indexed to body surface area; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PW, posterior wall; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

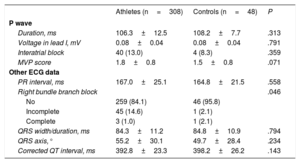

Table 3 shows data on ECG evaluation. There were no significant differences between athletes and controls in the electrocardiographic indices: P-wave duration (106.3±12.5 vs 108.2±7.7ms), IAB prevalence (40 [13.0%] vs 4 [8.3%]) and MVP score (1.8±0.84 vs 1.5±0.8). Only 1 case of advanced IAB was detected in an athlete, who was 37 years old, had no comorbidities, trained for 16hours per week, and did not have LA dilatation.

ECG data from athletes and controls

| Athletes (n=308) | Controls (n=48) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P wave | |||

| Duration, ms | 106.3±12.5 | 108.2±7.7 | .313 |

| Voltage in lead I, mV | 0.08±0.04 | 0.08±0.04 | .791 |

| Interatrial block | 40 (13.0) | 4 (8.3) | .359 |

| MVP score | 1.8±0.8 | 1.5±0.8 | .071 |

| Other ECG data | |||

| PR interval, ms | 167.0±25.1 | 164.8±21.5 | .558 |

| Right bundle branch block | .046 | ||

| No | 259 (84.1) | 46 (95.8) | |

| Incomplete | 45 (14.6) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Complete | 3 (1.0) | 1 (2.1) | |

| QRS width/duration, ms | 84.3±11.2 | 84.8±10.9 | .794 |

| QRS axis,° | 55.2±30.1 | 49.7±28.4 | .234 |

| Corrected QT interval, ms | 392.8±23.3 | 398.2±26.2 | .143 |

ECG, electrocardiogram; MVP, morphology-voltage-P-wave duration.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Table 4 shows the comparison of participants with and without LA dilatation. Those with LA dilatation had higher mean age, P-wave duration, IAB frequency, and MVP score (1.9±1.0 vs 1.7±0.7; P=.01). As only 5 controls had LA dilatation, the differences in the electrocardiographic parameters of atrial activation were mainly due to the athletes (table 5).

Clinical, echocardiographic, and electrocardiographic data from participants with and without left atrial dilatation

| Dilated LA (n=118) | Undilated LA (n=238) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 40.73±12.5 | 36.8±13.1 | .008 |

| Athlete | 113 (95.8) | 195 (81.9) | .001 |

| Male sex | 78 (66.1) | 178 (74.8) | .086 |

| Type of training | .111 | ||

| Resistance | 18 (15.3) | 17 (7.1) | |

| Strength | 20 (16.9) | 32 (13.4) | |

| Body mass index | 22.6±3.5 | 20.8±3.3 | .001 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.97±0.2 | 1.86±0.2 | .001 |

| Hours of sport per week | 10.0±5.1 | 10.6±4.6 | .519 |

| Hypertension | 5 (4.2) | 15 (6.3) | .334 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | .675 |

| Smoking | 5 (4.2) | 17 (7.1) | .215 |

| Dyslipidemia | 6 (5.1) | 22 (9.2) | .120 |

| LAVi, mL/m2 | 41.3±5.2 | 25.1±5.8 | .001 |

| Right atrial dilatation | 57 (48.3) | 68 (28.6) | .551 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 49 (41.4) | 38 (16.0) | .001 |

| LVEDD, mm | 52.6±4.1 | 49.9±5.1 | .001 |

| Transmitral filling pattern | .367 | ||

| Normal | 102 (86.4) | 215 (90.3) | |

| Impaired relaxation | 16 (13.6) | 22 (9.2) | |

| Pseudonormal or restrictive | 0 | 1 (0.4) | |

| E/e’ | 6.0±1.6 | 6.1±1.8 | .580 |

| P wave duration, ms | 110.2±13.9 | 104.7±10.5 | < .001 |

| P wave voltaje in lead I, mV | 0.08±0.04 | 0.08±0.05 | .916 |

| PR interval, ms | 172.4±27.6 | 163.89±22.5 | .002 |

| QRS width/duration, ms | 84.9±11.7 | 84.15±10.9 | .546 |

| QTc interval, ms | 394.8±25.9 | 392.9±22.7 | .479 |

| Right bundle branch block | .434 | ||

| No | 104 (88.1) | 201 (84.5) | |

| Incomplete | 12 (10.2) | 34 (14.3) | |

| Complete | 2 (1.7) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Interatrial block | .001 | ||

| No | 94 (79.7) | 217 (91.2) | |

| Partial | 24 (20.3) | 19 (8.0) | |

| Advanced | 0 | 1 (0.4) | |

| MVP score | 1.9±1 | 1.67±0.7 | .026 |

LA, left atrium; LAVi, left atrial volume indexed to body surface area; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; MVP, morphology-voltage-P-wave duration.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

P wave values in athletes and controls with and without left atrial dilatation

| Athletes (n=308) | LA dilatation (n=113) | No LA dilatation (n=195) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| P wave duration, ms | 110.3±14.1 | 103.9±10.9 | <.001 |

| Interatrial block | 23 (20.4) | 17 (8.8) | .004 |

| MVP score | 1.9±1.0 | 1.7±0.7 | .081 |

| Controls (n=48) | LA dilatation (n=5) | No LA dilatation (n=43) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P wave duration, ms | 108.4±7.4 | 108.1±7.8 | .939 |

| Interatrial block | 1 (20.0) | 3 (7.0) | .366 |

| MVP score | 2.0±1.2 | 1.5±0.4 | .177 |

LA, left atrium; MVP, morphology-voltage-P-wave duration.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

There was no significant correlation between P-wave duration and LAVi, either in the whole sample (linear correlation coefficient r=0.01; P=.901) or in the athlete group (r=0.004; P=.966).

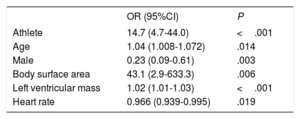

Table 6 shows the multivariate analysis for predictors of LA dilatation. Competitive training was independently associated with LA dilatation (odds ratio [OR], 14.7; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 4.7-44.0). We also forced inclusion in the model of cardiovascular risk factors, ventricular diameters, PR interval duration, and P-wave duration, which produced no significant changes in the association between participation in competitive sports and LA dilatation.

Multivariate analysis with independent predictors of left atrial dilatation

| OR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Athlete | 14.7 (4.7-44.0) | <.001 |

| Age | 1.04 (1.008-1.072) | .014 |

| Male | 0.23 (0.09-0.61) | .003 |

| Body surface area | 43.1 (2.9-633.3) | .006 |

| Left ventricular mass | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | <.001 |

| Heart rate | 0.966 (0.939-0.995) | .019 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

However, competitive training was not associated with P-wave duration (OR,1.02; 95%CI, 0.99-1.04; P=.19), MVP score (OR,1.4; 95%CI, 0.9-2.2; P=.14), or the presence of IAB (OR,1.4; 95%CI, 0.7-3.1; P=.34). The only variables that were independently associated with IAB were age in years (OR,1.05; 95%CI, 1.01-1.09; P=.015) and left ventricular mass in grams (OR,1.013; 95%CI, 1.004-1.023; P=.06).

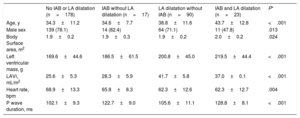

Table 7 shows the main differences in the clinical, echocardiographic, and electrocardiographic characteristics of the athletes according to the presence of IAB and LA dilatation. Compared with the other 3 groups, athletes with IAB and LA dilatation were older and more frequently female, and had a greater left ventricular mass.

Main differences in clinical, echocardiographic, and electrocardiographic characteristics in athletes, according to presence of interatrial block and left atrial dilatation

| No IAB or LA dilatation (n=178) | IAB without LA dilatation (n=17) | LA dilatation without IAB (n=90) | IAB and LA dilatation (n=23) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 34.3±11.2 | 34.6±7.7 | 38.8±11.6 | 43.7±12.8 | <.001 |

| Male sex | 139 (78.1) | 14 (82.4) | 64 (71.1) | 11 (47.8) | .013 |

| Body Surface area, m2 | 1.9±0.2 | 1.9±0.3 | 1.9±0.2 | 2.0±0.2 | .024 |

| Left ventricular mass, g | 169.6±44.6 | 186.5±61.5 | 200.8±45.0 | 219.5±44.4 | <.001 |

| LAVi, mL/m2 | 25.6±5.3 | 28.3±5.9 | 41.7±5.8 | 37.0±0.1 | <.001 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 68.9±13.3 | 65.8±8.3 | 62.3±12.6 | 62.3±12.7 | .004 |

| P wave duration, ms | 102.1±9.3 | 122.7±9.0 | 105.6±11.1 | 128.8±8.1 | <.001 |

IAB, interatrial block; LA, left atrium; LAVi, left atrial volume indexed to body surface area.

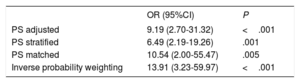

Table 8 shows the association of LA dilatation with competitive sport using propensity score adjustment.

Association between left atrial dilatation and participation in competitive sport using propensity score adjustment

| OR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| PS adjusted | 9.19 (2.70-31.32) | <.001 |

| PS stratified | 6.49 (2.19-19.26) | .001 |

| PS matched | 10.54 (2.00-55.47) | .005 |

| Inverse probability weighting | 13.91 (3.23-59.97) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PS, propensity score.

Our study shows that, despite being younger and healthier than controls, athletes had a far higher prevalence of LA dilatation, although this finding correlated poorly with electrocardiographic changes.

Left atrial dilatation and remodeling in athletes are practically defining characteristics of athlete's heart.3,4 However, the threshold for defining normal LA size in athletes is a matter of debate.5,17 Two meta-analyses have demonstrated that LA volume is significantly larger in athletes than in controls. However, the studies analyzed yielded heterogeneous results on the prevalence of LA dilatation, presumably due to differences in the sporting discipline (strength or resistance training), level of training, and age.18,19 Rates of LA dilatation of up to 42% to 8% have been described in elite rowers20 and professional basketball players,21,22 although severe dilatation is an uncommon finding. Our data confirm both the association between competitive sport and LA dilatation and that severe LA dilatation is rare (only 1.6% of our athletes).

The main contribution of the ALMUDAINA study is that it demonstrates that competitive training in athletes is not associated with longer P-wave duration or presence of IAB. Despite a high prevalence of LA dilatation, we found no significant changes in the atrial electrocardiographic parameters. A recent study in young athletes showed that less than 1% had a P-wave duration ≥ 120ms and a negative component ≥ 1mm deep in lead V1.23 Even in the general population, the electrocardiographic criteria for LA dilatation have shown low sensitivity.11,24,25 Furthermore, changes in P-wave duration and morphology may be due to an IAB in normal-sized atria. This has been demonstrated experimentally26 and in situations such as the presence of an atrial tumor, which can cause IAB without LA dilatation.27 Our study also supports the argument that LA dilatation and IAB are 2 different entities, as most of our athletes with LA dilatation did not have IAB.

However, the consensus documents of the American Heart Association regarding athletes recommend that any change in the P-wave, whether due to LA dilatation or IAB, should be considered a “P-wave abnormality”28,29; we think that this may actually increase confusion regarding LA assessment. Furthermore, the ECG index with the highest diagnostic sensitivity for LA dilatation (Morris index) has a low reproducibility,30 and P wave negativity increases when lead V1 is positioned in the second intercostal space.31 In addition, this pattern in V1 could simply represent an interatrial conduction defect.25

Nonetheless, compared with athletes without LA dilatation, those with LA dilatation had a longer P-wave duration (110 vs 104ms) and a higher prevalence of IAB (20% vs 9%). Therefore, we could hypothesize that it is likely that there is also a certain degree of electrical remodeling in athletes with LA dilatation. However, the fact that none of the athletes with LA dilatation had advanced IAB also indicates a less pathological LA dilatation in association with sports training.

The 2017 international recommendations for ECG interpretation in athletes emphasized that LA dilatation on ECG remains a borderline variant not requiring further cardiological assessment, unless accompanied by other abnormalities.29 This recommendation is supported by the findings of our study (competitive training was not associated with P-wave ECG indices).

Regarding the association of other variables with LA dilatation, our data are in agreement with previous studies reporting an association between age32,33 and female sex and LA dilatation.32,34

LimitationsCertain limitations of this study must be recognized. Left atrial volume index was calculated with 2-dimensional echocardiography and not cardiac magnetic resonance. Women were under-represented in the athlete group, and as the athletes’ hearts may have differential adaptations to exercise,23,35 our results are mainly extrapolable to the male subgroup. Our sample is heterogeneous, as it was not limited to a single sport and included athletes with different training levels and intensity. Although this could be viewed as a limitation, it also contributes to the generalizability of our findings. We did not analyze the correlation between LA function and stiffness (measured by strain).36–39 The mean age of the adult athletes in our study (36 years) may be considered relatively old. This may partly be because 89% did resistance sports (combined with strength in 17%). However, some previous studies in athletes in Spain were also performed in populations of relatively advanced age: 29,40 40,41 and 5242 years. The small number of controls (explained by the COVID-19 pandemic) is also a limitation, although in the different adjustment options with propensity scoring a clear association was maintained between LA dilatation and competitive sports. We do not believe that the characteristics of the controls recruited was influenced by the pandemic but rather by their low number. Of note, the prevalence of LA dilatation found in our control group (10%) was higher than previously reported in the general population of 35 years and older (6%),43 so the difference in LA dilatation prevalence between our group of athletes (37%) and the general population may be even greater. To date, this is the first study to assess the association between LA dilatation and P-wave electrocardiographic indices in athletes.

CONCLUSIONSLeft atrial dilatation is common in athletes, but is not accompanied by significant changes in electrocardiographic parameters. Our data support the hypothesis that LA dilatation and IAB are 2 different entities. These findings may not be extrapolable to younger athletes, in whom prospective targeted studies of LA dilatation and electrocardiographic parameters should be performed.

- –

The association between LA dilatation and atrial electrophysiological characteristics has not been analyzed in athletes, a group without an established definition of the upper limit of normality for LA size.

- –

ALMUDAINA is a multicenter study that evaluates the correlation between LA dilatation (based on anatomic criteria) and electrocardiographic parameters of atrial enlargement. Although LA dilatation is common in athletes, it is not accompanied by longer P-wave duration, higher prevalence of IAB, or higher MVP score (a predictor of risk of atrial fibrillation). Our data show that sport is associated with an atrial remodeling that has little expression on surface ECG and suggests that LA dilatation and IAB are different entities.

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSDefinition of study objectives and design (M. Martínez-Sellés, C. Herrera), data collection (all authors), data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing first draft of article (M. Martínez-Sellés, C. Herrera). All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors have no conflicts of interest. The authors would like to thank José María Bellón Cano, research statistician at the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón for performing the propensity score adjustment.

.