Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a safe and effective alternative to surgical treatment in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) and those who are inoperable or at high surgical risk. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the long-term survival of consecutive patients with severe AS treated with TAVI.

MethodsObservational, multicenter, prospective, follow-up study of consecutive patients with severe symptomatic AS treated by TAVI in 3 high-volume hospitals in Spain.

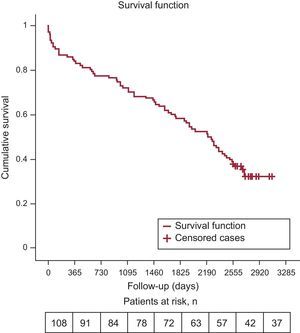

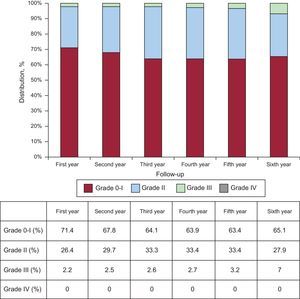

ResultsWe recruited 108 patients, treated with a self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis. The mean age at implantation was 78.6 ± 6.7 years, 49 (45.4%) were male and the mean logistic EuroSCORE was 16% ± 13.9%. The median follow-up was 6.1 years (2232 days). Survival rates at the end of years 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 were 84.3% (92.6% after hospitalization), 77.8%, 72.2%, 66.7%, 58.3%, and 52.8%. During follow-up, 71 patients (65.7%) died, 18 (25.3%) due to cardiac causes. Most (82.5%) survivors were in New York Heart Association class I or II. Six patients (5.5%) developed prosthetic valve dysfunction.

ConclusionsLong-term survival in AS patients after TAVI is acceptable. The main causes of death are cardiovascular in the first year and noncardiac causes in subsequent years. Valve function is maintained over time.

Keywords

In recent years, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has been widely recognized as a safe and effective alternative to surgical treatment for patients with severe inoperable aortic stenosis (AS) or at high surgical risk.1,2 At present, TAVI is indicated only for patients with severe symptomatic AS who are assessed by a multidisciplinary team and considered inoperable (indication I, level of evidence B) or who are operable but at high surgical risk (indication IIa, level of evidence B).3

Various studies show that the TAVI procedure yields good short- and mid-term results4–7; however, there is a paucity of long-term data on the durability and clinical outcomes of percutaneous valves.8 Recently, the first series was published with long-term results on the use of the Edwards-SAPIEN valve.9–12 In the case of the self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis, very little evidence is available from long-term follow-up because only a few studies have been published, with follow-up periods of 3 to 5 years.13–16

The main aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term mortality, clinical outcomes, and durability of the self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis at 3 Spanish hospitals with initial results that represent early experience with this treatment in Spain.17

METHODSStudy Design and PopulationThe study was designed as a multicenter, observational, prospective study with comprehensive follow-up of all consecutive patients with severe symptomatic AS treated by TAVI (CoreValve valve) at 3 high-volume Spanish hospitals between 20 December 2007 and 26 May 2009. This work describes the long-term follow-up of a cohort previously published by Avanzas et al.17 in 2010.

EndpointsThe primary endpoint of this study was to evaluate survival free of any-cause death in the long-term (> 6 years). The secondary endpoints were analysis of the causes of mortality (cardiac and noncardiac), clinical progress (New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class), and prosthetic function (maximum and mean gradients, effective valve area, and left ventricular function) during follow-up.

Study VariablesThe variables studied were included in a specially dedicated database. All variables related to follow-up were recorded, using the Valve Academy Research Consortium 2 (VARC-2) criteria18 as a reference:

- •

Mortality: all-cause mortality during follow-up.

- •

Cardiovascular mortality: deaths meeting 1 of the following criteria: any death due to cardiac cause, unexpected or unknown-cause death, death related to a complication of the procedure or treatment for a complication of the procedure, and death due to noncoronary vascular cause.

- •

Prosthetic dysfunction: mean valve gradient > 20mmHg; effective valve area < 0.9-1.1cm2; moderate-to-severe aortic regurgitation.

Yearly follow-up was performed as per protocol through a specialist or telephone consultation with all patients or relatives until the end of the study period or until patient death. Follow-up ended on June 1, 2016, representing a maximum follow-up of 8.5 years and minimum of 7.02 years for living patients at that date. There were no losses during clinical follow-up of the patients.

Statistical AnalysisA basic descriptive statistical study was performed, and all variables were tested for normal distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and/or box-plot in the case of continuous variables, and as number and percentage in the case of categorical variables. The survival study was performed by Kaplan-Meier analysis. All statistics were obtained using the SPSS statistical program, version 22 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Illinois, United States).

ResultsA total of 108 patients were included. The baseline characteristics for the population have been previously published.17 The mean age at the time of implantation was 78.6 ± 6.7 (range, 50-92) years; 49 (45.4%) patients were men, and the mean logistic EuroSCORE was 16% ± 13.9% (2.3%-86.9%). The success rate for the procedure was 98.1%. The median follow-up for all patients was 6.1 years (2232 days). For living patients at the end of follow-up, the median follow-up was 7.48 years (2731 days) with a maximum and minimum follow-up of 8.5 and 7.02 years (3086 and 2563 days).

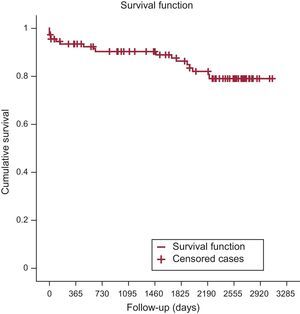

Primary Study Endpoint: Long-term SurvivalSurvival at the end of years 1 to 6 was 84.3% (92.6% after the hospitalization period), 77.8%, 72.2%, 66.7%, 58.3%, and 52.8%. The survival estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method for all-cause and cardiac mortality was 0.32 and 0.79, respectively (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The median survival time estimated by the same method was 2207 days (95% confidence interval, 1856-2557).

Secondary EndpointsTime Trend in Mortality and its CausesThe time trend in mortality during follow-up and its causes are listed in Table 1. A total of 71 (65.7%) patients died during the follow-up period: 18 (25.3%) due to cardiac cause, 5 (7%) during hospitalization, and 13 (18.3%) during subsequent follow-up. Among the 3 patients who died from cardiac arrest, 1 had a pacemaker (the other 2 had no known conduction abnormalities), and 2 had ventricular dysfunction. Among the 9 deaths due to heart failure after hospital discharge, 6 patients had ventricular dysfunction and 4 had grade III aortic regurgitation.

Evolution and Causes of Mortality During Follow-up

| Hospitalization | First year (except hospitalization) | Second year | Third year | Fourth year | Fifth year | Sixth year | Seventh year | Eighth year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n, yearly % | 8 (7.4) | 9 (8.3) | 7 (7.7) | 6 (7.1) | 6 (7.7) | 9 (12.5) | 6 (9.5) | 15 (26.3) | 5 (11.9) |

| Noncardiac, n | 3 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 5 |

| Causes | Respiratory failure (2) Vascular sepsis | Respiratory failure (3) SBP Pancreatitis Cancer Stroke | Sepsis (osteomyelitis) MDS Multiorgan failure Renal failure | Pulmonary sepsis Sepsis (pyelonephritis) Sepsis after hip surgery Multiorgan failure Renal failure (2) | Breast cancer (2) Stomach cancer Multiorgan failure Respiratory failure Pulmonary sepsis | Pulmonary sepsis (2) Sepsis after hip surgery Multiorgan failure Respiratory failure SAH | Multiorgan failure (2) Stomach cancer | Multiorgan failure (6) Abdominal sepsis (2) Pulmonary sepsis (2) Renal failure Stomach cancer Lung cancer | Multiorgan failure (4) Pulmonary sepsis |

| Cardiac, n | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Causes | Heart failure (3) Ventricular perforation (2) | Heart failure Sudden cardiac death | Heart failure (2) Sudden cardiac death | Heart failure (2) AMI | Heart failure (2) Sudden cardiac death | Heart failure (2) |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

At the end of follow-up, 31.6% of patients were in NYHA I and 50.9% in NYHA II. Data on functional class in the first 6 years of follow-up are shown in Figure 3.

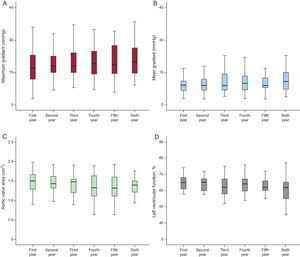

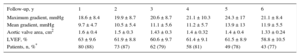

Valve FunctionThe echocardiographic time trends during follow-up (maximum and mean gradients, effective valve area, and left ventricular function) are shown in Table 2 and are compared according to follow-up year in Figure 4. The rates of aortic regurgitation > grade II observed by echocardiography in years 1 to 6 of follow-up were 2.2%, 2.5%, 2.6%, 2.7%, 3.2%, and 7.0% (Figure 5). Upon completion of follow-up and according to the VARC-2 criteria, 6 (5.5% of total) patients had valve dysfunction. There were no cases of severe prosthetic dysfunction requiring reoperation. In the first year of follow-up, 3 patients had moderate valve stenosis with mean gradients of 22, 22, and 27mmHg, respectively. Of those 3 patients, 1 died in the second year due to septic cause and the other 2 were alive at the end of follow-up, with no increase in the gradients. In the second, third, and fourth years, another 3 patients had mean gradients of 24, 22, and 23mmHg, with oscillations < 2mmHg up to the end of follow-up.

Time Trend in Echocardiographic Parameters During Follow-up

| Follow-up, y | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum gradient, mmHg | 18.6 ± 8.4 | 19.9 ± 8.7 | 20.6 ± 8.7 | 21.1 ± 10.3 | 24.3 ± 17 | 21.1 ± 8.4 |

| Mean gradient, mmHg | 9.7 ± 4.7 | 10.5 ± 5.4 | 11.1 ± 5.6 | 11.2 ± 5.7 | 13.9 ± 13 | 11.9 ± 5.5 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.43 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.32 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.33 ± 0.24 |

| LVEF, % | 63 ± 9.6 | 61.9 ± 8.8 | 60.6 ± 9.7 | 61.4 ± 9.1 | 61.5 ± 8.9 | 58.8 ± 10.5 |

| Patients, n, %* | 80 (88) | 73 (87) | 62 (79) | 58 (81) | 49 (78) | 43 (77) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The results of our series of patients who received a self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve, with a very long-term follow-up (median of 2232 days/6.1 years) show that mortality at the end of the sixth year of follow-up was high (47.2%), particularly due to noncardiac causes, and that valve durability was good (5.5% prosthetic dysfunction with no need for reoperation). Our data are taken from the multicenter cohort with the longest, protocol-based follow-up studied to date in Spain, as it includes the first patients treated with the self-expanding valve by this procedure.17 Complete clinical and echocardiographic parameters and the causes of death each year are listed.

At present, there is little information on long-term follow-up of TAVI. The currently published series can be analyzed according to the type of valve used, Edwards-SAPIEN and CoreValve, as these valves were used initially and, therefore, have longer follow-up periods. Most notably, the Edwards-SAPIEN valve was studied in a series by Toggweiler et al.9 with 88 patients, which reported a 5-year survival of 35% with yearly mortality rates of 17%, 26%, 47%, 58%, and 65%. Unbenhaun et al.11 reported a total mortality of 61.4% at 5 years, with yearly rates of 18.4%, 33.1%, 42.8%, 51.8%, and 61.4% and a final survival of 39.6%. Mortality data for arm B was also recently published by the PARTNER study,10 which observed yearly mortality rates of 30.7%, 43%, 53.9%, 64.1%, and 71.8%. A study by Escárcega et al.19 found that the survival of the transfemoral group was < 50% at 5 years. In our setting, experience has recently been published on follow-up at a single hospital in Spain12 with yearly mortality rates of 20.3%, 29.1%, 41.1%, 50.5%, and 68% and a final survival of 32%.

Regarding experience with TAVI using the CoreValve self-expanding valve, Barbanti et al.16 recently published their experience in a 5-year follow-up study of a cohort of 353 patients, reporting yearly mortality rates of 21%, 29%, 38%, 48%, and 55% and cardiovascular mortality rates of 10%, 14%, 19%, 23%, and 28%. In a study by Gulino et al.,15 the yearly survival of a cohort of 125 patients was 83.2%, 76.8%, 73.6%, and 66.3%. Codner et al.20 published data on a mixed series with 360 patients, 71% of whom were treated with CoreValve and 26% with SAPIEN, with 3- and 5-year mortality rates of 71.6% and 56.4%, respectively.

Consequently, it can be assumed that total 5-year mortality is between the rate of 71.8% reported by PARTNER B10 and the rate of 55% for the series studied by Barbanti et al.16 Our data are consistent with those studies, particularly with the series by Barbanti et al.,16 and underscore the fact that the highest mortality rate is seen in the first year of follow-up, a fact essentially explained by higher mortality rates in the first month due to procedure-related complications. Following hospital discharge, the main cause of mortality is noncardiac, due to the high rate of comorbidities in these patients. Infectious diseases, mainly as a complication of previous conditions, and respiratory failure are very common causes of mortality, followed by the development of other diseases clearly related to aging, such as heart failure, multiorgan failure, renal impairment, and cancer.

A very important data point of our sample is the proven durability of the valve, which is seen in the rate of valve dysfunction found in our study (5.5%). A comparison of this rate with data reported by other series is difficult: first, because there is little information on follow-up periods of similar length with the same valve, and second, due to the heterogeneity of the definition used to diagnose valve dysfunction. For instance, various series published with the Edwards-SAPIEN valve have reported that moderate-to-severe aortic regurgitation appeared in 3.8% of cases at 5 years.20 Barbanet et al.16 considered the sum of severe degeneration plus increased mean gradient above 20mmHg at 5 years and found a rate of prosthetic dysfunction of 4.2%, a figure comparable to ours, as well as the rate of 4.5% recently reported by Del Trigo et al.21 A series by Salinas et al.12 reported even higher (15.3%) valve dysfunction figures. In our series, there were no cases of prosthetic valve dysfunction requiring valve replacement, similar to the studies conducted by D’Onofrio et al.22 (at 3 years) and Salinas et al.12 and below the levels reported by Unbehaun et al.11 (3%), Toggweiler et al.9 (1.1%), Kapadia et al.10 (1.1%), Rodés-Cabau et al.8 at 4 years (0.6%), and Barbanti et al.16 (0.6%). In this regard, although additional studies are needed to understand this aspect more clearly, the valve durability observed in our series is consistent with the largest series published to date with the same valve.

LimitationsThe influence of postimplant regurgitation on mortality has been demonstrated,23 although quantitation of this influence in patients treated with TAVI remains a challenge. The echocardiographic parameters were quantitated at each individual site and, therefore, there could be some lack of homogeneity in the results. These methodological aspects should be considered in future studies, particularly with regard to the quantitation of residual aortic regurgitation. The number of patients is not very high, which could result in a partial bias in the results and prevent sufficient power to analyze predictive variables of the primary endpoint. Furthermore, the results refer to the first-generation self-expanding CoreValve valve and, therefore, are not applicable to the population currently being treated. The lack of reoperations for valve dysfunction, a finding inconsistent with those of other series, could be due to the small sample size and may have led to an underestimation of this complication.

CONCLUSIONSIn view of the results and limitations of our series, it can be concluded that long-term survival with TAVI is acceptable, as shown by the fact that more than half the patients survive beyond the sixth year. Although the main cause of mortality is cardiovascular in the first year, other causes more commonly seen with aging, such as infections and cancer, are more prevalent with longer follow-up. Patients also show an acceptable long-term functional status. In our series, although there was a slight, progressive increase in valve gradients, valve functionality remained steady over time. Further studies with even longer follow-up are needed to confirm the functional durability of TAVI and to investigate potential factors related to the procedure.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTSJ.H. Alonso-Briales, J.M. Hernández-García, and C. Morís are CoreValve proctors.

- –

In recent years, TAVI has been widely recognized as a safe and effective alternative to surgical treatment for patients with severe inoperable AS or at high surgical risk. Various studies show that TAVI provides good short- and mid-term results; however, there is a paucity of data on the long-term clinical outcomes and durability of percutaneous valves.

- –

This series reports on clinical outcomes for the first 108 patients treated with the self-expanding CoreValve valve in our country and, therefore, are the earliest patients with available follow-up (7.02-8.5 years). There is a lack of evidence on the durability of this valve, as only a few studies have follow-up periods of 3 to 5 years. Comprehensive data are listed for clinical and echocardiographic parameters and the causes of death each year.