Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Based on the results of clinical trials, drug-eluting stents (DES) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of de novo coronary lesions, seen to be relatively noncomplex on angiography.1 However, the postmarketing use of these devices has become more common, even in situations where there is currently little evidence of their efficacy and safety, for example, to treat in-stent restenosis, surgical grafts, chronic occlusions, and bifurcation, ostial, and left main coronary artery lesions. This has led to on-label and off-label indications (approved and not approved, respectively), based on compliance with the criteria specified by the FDA, which has recently issued a warning that off-label use may be associated with an excess of adverse clinical events.2,3

The clinical consequences of using DES for off-label indications are not well defined. Two observational, prospective multicenter registries are currently available. The DEScover registry (from the acronym DES, drug-eluting stents) excluded early events, but found that off-label use of DES was not associated with a higher risk of a composite of death, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and stent thrombosis (ST) at 1 year of follow-up (hazard ratio [HR], 1.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.54)4 after adjusting for age, sex, geographical area, procedure priority, prior AMI, prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), heart failure, peripheral artery disease, renal failure, diabetes, lung disease, smoking habit, number of diseased vessels and "attempted" lesions, use of beta-blockers, clopidogrel or ticlopidine, and complications. In the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug-Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) study,5 off-label use was related to a higher risk of a composite of death, AMI, and target vessel revascularization (TVR) in comparison with on-label use (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.74-2.67), after adjusting for age, sex, weight, diabetes, heart failure, renal failure, and acute coronary syndrome. However, the prognostic information provided by both studies was limited by the short follow-up period (up to 1 year postimplant).

In this study we analyze the frequency of drug-eluting stent implantation for off-label indications and assessed the clinical outcome compared with on-label indications in routine clinical practice after prolonged follow-up.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a cohort follow-up study that included consecutive patients who had received at least 1 paclitaxeleluting stent (PES) in our interventional cardiology unit between June 2003 and February 2005. These devices were the only DES available in our laboratory at that time.

The revascularization procedures were performed in accordance with current clinical practice guidelines for PCI.6 The decision regarding PES implantation was taken by the interventional cardiologist, based on the clinical and angiographic characteristics of each patient. In general, PES were implanted in lesions at a high risk of restenosis, such as chronic occlusions, lesions in surgical grafts or small vessel, in-stent restenosis, or long lesions. A 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel was administered to all patients who were not taking this medication. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used at discretion of the interventional cardiologist. However, these drugs were used mainly in the treatment of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction under the Programa Gallego de Atención al IAM (PROGALIAM, Galician AMI Care Program). Following the interventional procedure, patients were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 6 months, to continue later with either aspirin or clopidogrel indefinitely.

The clinical and angiographic characteristics of the population at baseline were recorded following a detailed review of the medical histories, the computer database of our unit, and the coronary angiography results. Patients were then classified into 2 groups: PES on-label and off-label use.1,4,5,7 The following situations were considered off-label indications: multiple PCI (revascularization of more than 1 coronary lesion), instent restenosis, lesions in surgical grafts (venous or arterial), total stent length 336 mm, small vessels (stent diameter <2.5 mm), primary or rescue angioplasty, left main coronary artery, bifurcation lesions, ostial lesions, and chronic total occlusions. Implantation of PES for lesions without any of the characteristics mentioned was defined as on-label use. Because most clinical studies with DES exclude patients who receive a PES during primary or rescue angioplasty, these patients were included in the off-label group. Patients who had an indication for scheduled coronary angiography for a STEMI that was treated by fibrinolysis or not reperfused were classified according to the angiographic characteristics.

The primary end points of the study were a composite of death and nonfatal AMI after PES implant and a composite of death, AMI, and TVR after prolonged clinical follow-up. Death by any cause, cardiac death, AMI, TVR, and ST were other end points of our study.

AMI was defined according to the criteria of the European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology8 consensus document, which consist of a cardiac troponin value greater than the 99th percentile of the reference values and at least 1 of the following: ischemic symptoms, pathological Q waves on electrocardiography, electrocardiogram changes consistent with ischemia (ST elevation or depression), or coronary revascularization.

ST included subacute thromboses (those occurring between 24 hours and 30 days postimplant), late thromboses (at 30-365 days), and very late thromboses (after 1 year), both probable and definite, defined in accordance with the consensus of the Academic Research Consortium.9 Probable thrombosis included sudden deaths of unknown cause within 30 days after PCI and AMI in the territory of a previously implanted stent without confirming thrombus. Definite thrombosis was considered to be stent occlusion by a thrombus confirmed by coronary angiography or necropsy.

Antiplatelet discontinuation was defined as the need to stop antiplatelet therapy for at least 7 days, regardless of the reason.

We performed a comprehensive review of the clinical progress of these patients after PCI, recording the main clinical events throughout follow-up. Phone contact was used to confirm the vital status of the patient and ask about any antiplatelet therapy followed, in particular to mention the need to discontinue such therapy during follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean (SD) and categorical variables as absolute frequency (relative frequency, %). The c2 test or Fisher´s exact test was used to assess the relationship between two categorical variables. To compare 2 means, we used Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test according to normal distribution of the variable.

The long-term incidence of the primary end points of the study was estimated by Kaplan-Meier. Log rank test was used to compare the chronological course of events between off-label and on-label use.

In order to estimate the effect of off-label use of PES for the main clinical events, we performed Cox stepwise regression using 0.05 and 0.1 as addition and removal criteria, respectively, with the following secondary covariables: age, sex, diabetes, prior AMI, prior revascularization (surgical or percutaneous), glomerular filtration rate (estimated by the MDRD-4 formula10), acute coronary syndrome, number of diseased vessels, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and antiplatelet discontinuation, along with type of indication for which the stent was implanted. A P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 12.0 was used for the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Between June 2003 and February 2005, our interventional cardiology unit performed implantation of at least 1 PES in 604 patients, most of whom presented at least 1 off-label indication for PES (464 patients; 76.8%). Table 1 summarizes the off-label indications and frequency in our sample. The baseline characteristics of the off-label and on-label groups are shown in Table 2. Patients in the off-label group presented a poorer clinical profile than those in the on-label group: older age and more likely to have prior history of AMI, coronary revascularization (surgical and percutaneous), and multivessel disease.

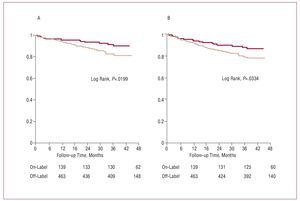

Follow-up was completed in 581 patients (96.2% of the sample). After prolonged follow-up (median, 34.3 [interquartile range, 8.5] months), a composite of death and AMI and a composite of death, AMI, and TVR were more common in the off-label group of PES (Figure 1, Table 3). Following statistical adjustment, off-label use of PES was independently associated with a higher risk of both death and AMI and of death, AMI, and TVR (Table 4).

Figure 1. Survival free of death or acute myocardial infarction (A) and death, acute myocardial infarction, or target vessel revascularization (B): comparison between off-label use (light line) and on-label use (dark line).

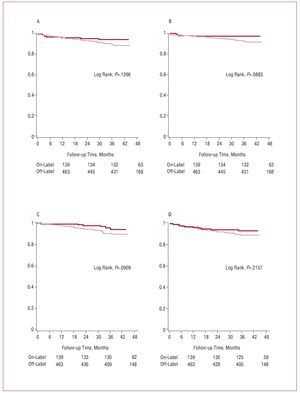

The individual end points were more common in the off-label group for PES, but not statistically significant in the log rank test (Figure 2, Table 3) or after adjustment (Table 4).

Figure 2. Survival free of death (A), cardiac death (B), acute myocardial infarction (C), and target vessel revascularization (D): comparison between off-label use (light line) and on-label use (dark line).

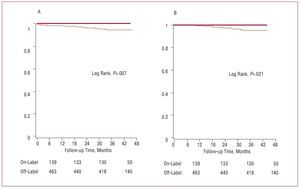

The cumulative incidence of ST was 3.8% in the sample (23 cases in 604 patients) (Table 5), mainly because of the contribution of late thrombosis classified as definite (17 cases; incidence, 2.8%) and was seen only in the off-label group (ST incidence, 5%; incidence of definite late thrombosis, 3.7%) (Figure 3, Table 5). As a result, we were unable to fit a Cox multivariate model. Differences were not observed for subacute thrombosis, but were observed for late thrombosis and total thrombosis, conditions that were more common in the off-label group (Table 5). From a clinical standpoint, ST was accompanied by elevated mortality (9 deaths, 39%), with 3 sudden deaths due to probable subacute thrombosis, 4 deaths during the acute phase from postinfarction cardiogenic shock due to late thrombosis classified as definite, and 2 additional deaths during follow-up (1 from heart failure secondary to postinfarction systolic dysfunction after late thrombosis and another from metastatic pancreatic cancer). Multiple PCIs, long lesions, or lesions in small vessels were more common among patients with ST than in patients without. There were no differences in other off-label indications (Table 1).

Figure 3. Survival free of stent thrombosis (A) and late and very late thrombosis (B) classified as definite: comparison between off-label use (light line) and on-label use (dark line).

DISCUSSION

Frequency of Off-Label Use

In routine clinical practice of our interventional cardiology unit, off-label use of DES was predominant (>75% of the sample). This percentage was higher than previously reported values. In the American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR),11 the first article to address the topic, off-label use accounted for 24% (49 757 out of 206 733 procedures). Two large-scale registries in the United States published later reported 47%4 and 55%.5 A recent Italian study12 found that 65% of patients received a DES for an off-label indication.

However, the criteria used to define off-label use of DES differ. The NCDR included only STEMI, in-stent restenosis, lesions in surgical grafts, and chronic total occlusions.11 The DEScover registry4 used definitions similar to those in this study, although patients with AMI were classified according to angiographic characteristics alone. However, in the EVENT registry,5 multiple PCI procedures, bifurcation and surgical graft lesions, AMI, chronic occlusions, diameter >4 mm, left main coronary artery, and LVEF <25% were the criteria used. Lastly, Qasim et al12 defined off-label indications as AMI, LVEF <30%, in-stent restenosis, bifurcation or ostial lesions, and surgical graft or left main coronary artery lesions.

Unquestionably, the definitions used by the different studies explain the differences found in the frequency of off-label use of DES. Moreover, the inherent financial restrictions of our public healthcare system could have driven the use of PES in more complex situations, in which off-label indications are more common, and may have also contributed to the higher percentage of off-label use in our series.

Long-Term Clinical Results

After a prolonged follow-up, off-label PES use was associated with a higher risk of adverse clinical events, whether a composite of death and AMI or a composite of death, AMI, and TVR. These findings complement the two U.S. multicenter registries cited4,5 and call into question the safety of DES in off-label indications, for which their use has not been adequately investigated. Our results may be due to the more severe clinical profile of this patient group (Table 2). Off-label use appears to select a subset of patients who have ischemic heart disease with a poor cardiovascular prognosis. It cannot be ruled out that the use of these devices may have contributed to the results by a higher incidence of ST, in particular, late and very late thrombosis (Table 5).

In fact, the incidence of ST is one of the highest reported to date (3.8% of the cohort of 604 patients), although consistent with the findings of recent studies.13,14

Our series had a high incidence of late to very late stent thrombosis classified as definite (2.8% of all patients). In our opinion, the long follow-up period (one of the longest available to date) has allowed us to detect the highest possible number of late thromboses and appears to be the main reason for the incidence of ST we report, particularly in view of the appearance of ST classified as definite, which is constant over time.14 Likewise, the incidence of ST in the off-label use group is noteworthy (5% of the total, mainly because of the contribution of late and very late thrombosis classified as definite, which had an incidence of 3.7%). However, in 2 multicenter registries in the United States, off-label use of DES was related to a higher incidence of ST in the first year postimplant.4,5 For example, the cumulative 1-year incidence of ST was 1.6% in the off-label group and 0.9% in the on-label group in a study by Win et al.5 Because late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents is common,14 a follow-up almost 3 times as long appears to explain the considerable incidence of ST seen in this study (taking into account the inherent limitations of the small sample size and the differences in definitions of off-label use). In addition, ST-related mortality would explain a significant percentage of deaths in the off-label group (8 cardiac deaths [17.4%] among a total of 46 deaths). An analysis of the Reduction of Restenosis in Saphenous Vein Grafts with Cypher Stent (RRISC) study revealed high mortality in patients treated with a sirolimus-eluting stent compared with patients who received conventional stents (HR=3.4; 95% CI, 2.2-7.3), which could be related to ST: 3 of the 11 deaths were sudden death and 1 was very late thrombosis.15 Other studies on DES in specific indications have also reported high short-term rates of ST.16-18 The high risk of ST and its clinical consequences could contribute to the risk of combined adverse events associated with the off-label use of PES detected in this study. In terms of off-label indications, multiple procedures, stent length >36 mm, and stent diameter <2.5 mm were more common among patients who experienced ST, a finding consistent with previous studies.19

Moreover, although individual events were observed more often among the off-label group, the differences were not statistically significant. This study lacked statistical power to detect differences in these events due to a modest sample size, similar to Qasin et al,14 who also found no differences in the risk of mortality or infarction. In 2 large-scale registries in the United States,4,5 off-label use of DES was not related to higher 1-year mortality, but was related to a higher risk of TVR. Regarding AMI, these studies had controversial results. The DEScover study4 reported a higher 30-day incidence of AMI in the off-label group, but not for untested use nor for off-label and on-label use at 1 year postimplant. After the statistical fit, there were no differences. Conversely, in the EVENT registry, off-label use was accompanied by a higher risk of AMI at both 6 and 12 months.5 However, the incidence of AMI is disproportionately high in that study, particularly in the first 6 months (10.5% of off-label group vs 4.5% of on-label), which could be due to a selection bias. Publication of the long-term results of these registries would certainly provide more information on the clinical outcome of drug-eluting stents in off-label indications.

Limitations of the Study

Apart from those mentioned above, our study may have several limitations, mainly with regard to the design (single-center follow-up observational study of a historical cohort). Patient follow-up was not complete. Losses during follow-up tend to be related to a higher number of events which, if they were known, could affect the study results. The data for the independent variables were not specifically combined in this study, which means that information bias may exist. The assessment of antiplatelet therapy and discontinuation during follow-up are subject to the possibility of anamnesis bias. Confounding variables not considered in the study, but possibly contributing to the differences existing after statistical adjustment, may have existed. The modest number of events may have led to unstable models in the multivariate analysis; thus, our results should be interpreted with caution. In addition, these findings stem from routine practice at our interventional cardiology unit and may not be reproducible at other units with different policies regarding DES implant. Only patients who received PES were included and, therefore, these results are applicable only to such devices, and not to sirolimus-eluting stents. Because there was no comparative group composed of patients who received a bare metal stent or underwent coronary artery bypass grafting in similar clinical situations, these therapeutic strategies could not be compared. The prognostic implications, whether early (during initial admission or at 30 days) or mid-term (at 1 year postimplant), could not be assessed because of the small number of events. However, the study was not designed for this purpose. Our study also could not establish differences between off-label and on-label use of PES because they were combined in the same category. However, in clinical practice one or more of these characteristics are often seen in a patient, and this distinction would require a large sample, something difficult to obtain with a single-center study. For the same reason, it was not possible to assess the specific prognostic contribution of each characteristic on which the distinction between off-label and on-label use is based.

CONCLUSIONS

In this retrospective analysis, off-label PES use was associated with a high risk of combined adverse clinical events in comparison with on-label use. As a result, the certainty of generalizing the use of such devices in situations that have not been adequately investigated is questionable. Patients with off-label indications presented a poorer clinical profile, which may explain these results. However, ST (in particular late and very late thrombosis classified as definite) is a serious event that appears to occur mainly in these off-label indications and with a non-negligible frequency (incidence of up to 5% for ST and 3.7% for late or very late thrombosis classified as definite) and may also have contributed to this high risk of events. New studies are needed to assess the safety and efficacy of DES in these clinical situations.

SEE EDITORIAL ON PAGES 674-7

ABBREVIATIONS

AMI, acute myocardial infarction

DES: drug-eluting stents

PES: paclitaxel-eluting stents

ST: stent thrombosis

STEMI: acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

TVR: target vessel revascularization

Correspondence: Dr. X. Flores Ríos.

Servicio de Cardiología. Hospital Juan Canalejo. As Xubias, s/n. 15006 A Coruña. España.

E-mail: xacobeflores@yahoo.es

Received September 22, 2007.

Accepted for publication March 24, 2008.