Evaluating patient outcomes following cardiac surgery is a means of measuring the quality of that surgery. The present study analyzes survival and the risk factors associated with mid-term mortality of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in Son Dureta University Hospital (Palma, Balearic Islands, Spain).

MethodsFrom November 2002 thru December 2007, 1938 patients underwent interventions. Patients were stratified in 4 age groups. Of 1900 patients discharged from hospital, 1844 were followed until December 31, 2008. Following discharge, we constructed Kaplan-Meier survival curves and performed Cox regression analysis to determine which variables associated with mid-term mortality.

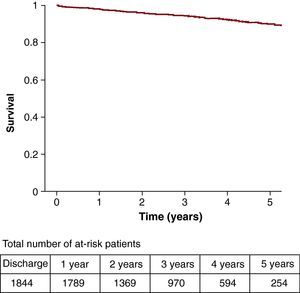

ResultsIn-hospital mortality of the 1,938 patients was 1.96% (CI 95%, 1.36%-2.6%). Survival probability at 1, 3 and 5years follow-up was 98%, 94% and 90%, respectively. Mean follow-up was 3.2 (0.01-6.06) years. Patients aged ≥70years showed a lower survival rate than those aged <70 log rank test i P<.0001). At the end of follow-up, mortality was 6.5% (CI 95%, 5.4%-7.7%). Age ≥70years, a history of severe ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <30 severe pulmonary hypertension diabetes mellitus preoperative anemia postoperative stroke and hospital stay were independently associated with mid-term mortality

ConclusionsMid-term survival after discharge was highly satisfactory. Mid-term mortality varied with age and other pre- and postoperative factors.

Keywords

The in-hospital morbidity and mortality of patients undergoing cardiac surgery have gradually fallen despite the progressive aging and increasing complexity of the population.1 Short- and mid-term survival and quality of life of patients discharged from hospital after cardiac surgery have also improved. This has been observed in isolated coronary surgery, valvular surgery, and combined coronary and valvular surgery, both in octogenarians and in patients with severe left ventricular failure.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Data on short- and mid-term survival of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in Spain is scarce. However, interesting studies of survival and quality of life following a first aortocoronary graft (ARCA)7 and of octogenarians operated for a range of cardiac conditions have recently been published.8 To determine the quality of cardiac surgery in any given hospital requires a comparison with other centers. However, differences in selecting patients to be studied and the great heterogeneity of the risk factors that are present and are analyzed make this difficult. In Europe, the EuroSCORE scale9 is frequently used to estimate surgical risk and is useful when predicting short- and long-term mortality10, 11, 12, 13 and comparing published results.

Age is a risk factor that is independent of in-hospital mortality and mid-term survival14, 15 following cardiac surgery. However, the issue has not been sufficiently studied in Spain, and in the same geographic area, for us to compare survival of patients undergoing cardiac surgery with survival in their reference population. The objective of the present study is to analyze mid-term survival of patients undergoing cardiac surgery at the Hospital Universitario Son Dureta (Palma de Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain). We also investigate the effect of age and the potential risk factors associated with mid-term mortality.

Methods PatientsWe enrolled all consecutive patients aged >17years undergoing major cardiac surgery in our center from November 2002 thru December 2007. Hospital Universitario Son Dureta is the public health service reference center for cardiac surgery in the Balearic Islands autonomous community, caring for nearly 1 million inhabitants. Three private centers also perform cardiac surgery. Patients received postoperative care in the cardiac surgery intensive care unit (ICU) according to a standardized protocol. For patients undergoing >1 intervention on different occasions, only their first intervention in this center was included, cutting the study population to 1938 patients. Given the growing population >80years old, we stratified patients into 4 age groups: <60, 60-69, 70-79 and ≥80years.

Pre-, intra- and postoperative data were obtained from our cardiac surgery database. Data were recorded prospectively by intensive care physicians and cardiac surgeons. The variables we analyzed were the classic cardiovascular risk factors (Table 1) and those included in the logistic scale of surgical risk evaluation (Logistic EuroSCORE).16 We also studied specific variables by surgery type and by peri- and postoperative complications.

Table 1. Preoperative Variables by Age Group (n=1938).

| Variables | <60 years | 60-69 years | 70-79 years | 80-89 years | P |

| Patients | 605 | 575 | 691 | 67 | |

| Age (years) | 49.6 ± 8.9 | 65 ± 2.9 | 74.1 ± 2.7 | 81.4 ± 1.4 | <.0001 |

| Women | 160 (26.4) | 167 (29) | 272 (39.4) | 27 (40.3) | <.0001 |

| Surgery | <.0001 | ||||

| Coronary | 266 (44) | 265 (46) | 252 (36.5) | 21 (31.3) | |

| Valvular | 193 (32) | 179 (31.1) | 235 (34) | 22 (32.8) | |

| Coronary+valvular | 30 (5) | 78 (13) | 157 (22.7) | 23 (34.3) | |

| Other | 116 (19.2) | 53 (9.2) | 47 (6.8) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Type of surgery | .006 | ||||

| Programmed | 524 (86.6) | 525 (91.3) | 637 (92.2) | 60 (89.6) | |

| Urgent | 81 (13.4) | 50 (8.7) | 54 (7.8) | 7 (10.4) | |

| Weight (kg) | 78.3 ± 15.9 | 77.1 ± 13 | 73 ± 11.7 | 71.8 ± 13.6 | <.0001 |

| Height (cm) | 165.4 ± 17.9 | 162.8 ± 16.5 | 159 ± 18.8 | 160.8 ± 8.1 | <.0001 |

| BMI | 27.98 ± 5.14 | 28.66 ± 4.47 | 28.26 ± 4.27 | 27.7 ± 4.49 | .058 |

| Smokers | 218 (36) | 94 (16.4) | 51 (7.4) | 1 (1.5) | <.0001 |

| HBP | 277 (45.8) | 371 (64.6) | 489 (70.8) | 43 (64.2) | <.0001 |

| Previous AMI | 167 (27.6) | 150 (26.1) | 193 (27.9) | 18 (26.9) | .904 |

| EF <30% | 19 (3.1) | 28 (4.9) | 22 (3.2) | 7 (9.2) | .012 |

| Severe PHT | 42 (6.9) | 27 (4.7) | 38 (5.5) | 1 (1.5) | .184 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 115 (19) | 196 (34) | 254 (37) | 21 (31.3) | <.0001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 35 (5.8) | 62 (10.8) | 65 (9.4) | 1 (1.5) | .002 |

| COPD | 70 (11.6) | 96 (16.7) | 91 (13.2) | 7 (10.4) | .056 |

| CKF | 23 (3.8) | 57 (9.9) | 89 (12.9) | 11 (16.4) | <.0001 |

| Dialysis | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 4 (0.6) | 0 | .92 |

| Stroke | 43 (7.1) | 61 (10.6) | 72 (10.4) | 7 (10.4) | .13 |

| Previous CS | 44 (7.3) | 34 (5.9) | 43 (6.2) | 2 (3) | .506 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 2.3 (1.5-4.7) | 3.7 (2.4-6.2) | 6.6 (4.5-10.7) | 11.1 (7-19.9) | <.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.4 ± 1.8 | 13.1 ± 1.7 | 12.7 ± 1.7 | 12.4 ± 1.7 | <.0001 |

| Preoperative anemia | 174 (29) | 198 (34) | 303 (44) | 35 (52) | <.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | .049 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; CKF, chronic kidney failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CS, cardiac surgery; EF, ejection fraction; HBP, high blood pressure; PHT, pulmonary hypertension.

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The postoperative cardiac complications analyzed were cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, cardiogenic shock, and acute myocardial infarction. We defined acute myocardial infarction as presence of new Q waves or electrocardiographic changes typical of acute ischemia and a creatine kinase MB fraction level 5 times greater than the upper limit for normal.

Noncardiac complications included acute stroke, renal dysfunction, and respiratory infections. We defined postoperative stroke as the appearance of a persistent focal neurologic deficit during ≥24h, confirmed by computerized tomography. Center for Disease Control guidelines diagnostic criteria for mediastinitis and pneumonia were applied. Mechanical ventilation time was defined as the period when patients needed ventilator support following cardiac surgery, from ICU admission to extubation, including reintubation time. Hospital stay included the period between cardiac surgery and discharge and ICU stay following cardiac surgery, including readmission.

Follow-upIn-hospital mortality was calculated by identifying all deaths during hospitalization. Mortality following discharge was calculated from data on patient life status at December 31, 2008, provided by the autonomous community's statistics office (Servicio Balear de Estadística). We consulted electronic health records to determine whether the 6 patients who were not Spanish subjects (no Spanish ID number) contacted the health service following discharge. We excluded from survival analysis 56 patients lost during follow-up. The hospital research committee authorized this study.

Statistical AnalysisThe distribution of quantitative variables is expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between age groups were compared with analysis of variance and the Bonferroni correction. Nonsymmetric differences are expressed as median [interquartile range] and differences between groups were compared with the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute values and percentages and differences between these were analyzed with chi-squared. Preoperative risk was calculated using the logistic EuroSCORE model.16 We used Cox regression analysis to determine whether age and other potential prognostic variables did or did not associate with mid-term mortality. The model was constructed by selecting variables associated with pre- and postoperative mortality and giving P<.1 statistical significance in univariate analysis. Given that mortality in patients ≥70years old was greater than in those <70, and that differences between patients ≥80years and those aged 71-79 were not statistically significant, we analyzed 2 age groups (<70 and ≥70years). We estimated proportional risk and to do so we excluded in-hospital deaths.

Following discharge, survival during the follow-up period was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. We considered censored those patients who survived to 31 December 2008 and those who were alive when last contacted prior to the closure of our study period. We calculated survival rates by age group and by sex. Statistical analysis used SPSS 15.0 for Windows.

ResultsMean age of the 1938 patients was 64±11.9years; 32.3% were women. Stratification into 4 age groups was: <60years (n=605), 60-69 (n=575), 70-79 (n=691) and 80-89 (n=67). Logistic EuroSCORE was 6.8±7.4 (median 4.4 [interquartile range, 2.5-8.1]). Total in-hospital mortality was 1.96% (n=38) (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.36%-2.6%).

Table 1 summarizes patients’ main preoperative variables. The group of older patients (≥70years) included more women and had greater prevalence of high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, severe ventricular dysfunction, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney failure, and preoperative anemia. Indication for urgent cardiac surgery was more frequent in patients <70years; for combined valvular and coronary surgery it was more frequent in those >70years. Prevalence of severe pulmonary hypertension was 5.6%. In the mitral valve surgery group (n=378), pulmonary hypertension was severe in 16% of patients.

Table 2 presents the main operative variables of interventions with and without extracorporeal circulation (n=109; 5.6%). In coronary revascularization surgery, younger patients received more grafts; aortic valve replacement surgery was more frequent in older patients. In patients undergoing other interventions, 58% were on the aorta. This group included patients undergoing septal myectomies, cardiac tumor excision, and cardiac injury repair. Red blood cell concentrate transfusions were administered to 1376 patients (70%). Postoperative complications are shown in Table 3. In older patients (≥70years), incidence of atrial fibrillation, ICU mechanical ventilation time, and hospital stay were greater than in those aged <70, and the differences were statistically significant.

Table 2. Characteristics of Patients (n=1938).

| Variables | <60 years | 60-69 years | 70-79 years | 80-89 years | P |

| Patients | 605 | 575 | 691 | 67 | |

| Number of grafts | 2.9 ± 1 | 2.6 ± 1 | 2.4 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.9 | <.0001 |

| Aortic valve replacement | 167 (27.6) | 195 (33.9) | 326 (47.2) | 41 (61.2) | <.0001 |

| ECC time (min) a | 106 ± 43.9 | 100 ± 37 | 102 ± 38.4 | 89 ± 31.3 | .002 |

| Ischemia time (min)a | 76 ± 35.6 | 72 ± 31.7 | 75 ± 33.3 | 67 ± 26 | .079 |

| Red blood cells (units) | 3.7 ± 3.2 | 3.2 ± 2.8 | 3.7 ± 2.8 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | .094 |

ECC, extracorporeal circulation.

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

a Patients operated with ECC, n=1829.

Table 3. Postoperative Complications by Age Group (n=1938).

| Variables | <60 years | 60-69 years | 70-79 years | 80-89 years | P |

| Patients | 605 | 575 | 691 | 67 | |

| AMI | 19 (3.1) | 16 (2.8) | 24 (3.5) | 3 (4.5) | .839 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 11 (1.8) | 11 (1.9) | 22 (3.2) | 0 | .169 |

| VF | 7 (1.2) | 8 (1.4) | 8 (1.2) | 0 | .796 |

| AF | 97 (16) | 114 (19.8) | 169 (24.5) | 17 (25.4) | .002 |

| Reoperation | 10 (1.7) | 10 (1.7) | 23 (3.3) | 3 (4.5) | .096 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (0.5) | 7 (1.2) | 14 (2) | 1 (1.5) | .11 |

| Mediastinitis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | .779 |

| Stroke | 7 (1.2) | 5 (0.9) | 9 (1.3) | 0 | .72 |

| MV time (h) | 12.5 ± 43.3 | 14.4 ± 63.3 | 22.2 ± 105.3 | 22.8 ± 102.9 | <.0001 |

| Median | 5 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 | |

| MV>72 h | 15 (2.5) | 6 (1) | 12 (1.7) | 0 | .184 |

| ICU stay (days) | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.6 ± 5.6 | 4.2 ± 5.1 | 3.7 ± 5 | .104 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 14.3 ± 10.5 | 15.2 ± 11.7 | 17.5 ± 12.4 | 17.4 ± 11.5 | .0001 |

| Median | 10 | 11 | 13 | 15 | |

| In-hospital mortality | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 23 (3.3) | 3 (4.5) | <.002 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ICU, intensive care unit; MV, mechanical ventilation; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

In-hospital mortality increased with age and was significantly greater in those aged ≥70 than in younger patients. Logistic EuroSCORE increases with age and overestimates mortality found in the 4 age groups.

We excluded 56 of the 1900 patients discharged from hospital because they were lost to follow-up. Their mean age was 59±15.2years, 25% were women and logistic EuroSCORE was 8.8±10.1 (median 4.8 [2.5-9.9]). Coronary surgery was performed on 52%, and 30% underwent isolated valvular surgery or combined valvular and coronary surgery. Mean ICU stay was 4.5days and mean hospital stay was 17. Postoperative complications were infrequent (atrial fibrillation, 27%; acute myocardial infarction, 3.6%; ventricular fibrillation, pneumonia, mediastinitis, and transitory ischemic accident, 0%).

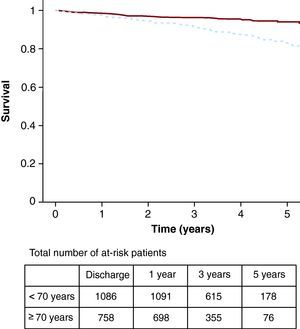

Survival analysis included 1844 patients. Mean age, percentage of women, and distribution by age group were similar to those in the total population described earlier (data not shown). At the end of follow-up, mortality was 6.5% (n=120) (95% CI, 5.4%-7.7%). Patients aged ≥70 (n=718) presented 10% mortality (n=48) (95% CI, 7.8%-12.3%) versus 4.5% (n=72) (95% CI, 3.0%-5.5%; P<.0001) in patients aged <70years (n=1126). The logistic EuroSCORE of patients still alive at the end of follow-up was much lower (6.1±6.1; median, 4.2 [2.3-7.4]) than that of those who died during follow-up (11.9±13.2; median, 7.6 [2.9-13.9]; P<.0001).

Survival probability at 1, 3, and 5years of patients discharged from hospital (n=1844) was 98%, 94%, and 90%, respectively (Figure 1). Mean follow-up of these patients lasted 3.2 (0.01-6.06) years and was similar in the 4 age groups. Survival (Figure 2) of patients aged ≥70 was lower than in those aged <70years (P<.0001). Survival probability in patients aged ≥70 at 1, 3, and 5years was 97%, 91%, and 83%, respectively, versus 98%, 96%, and 93% in those aged <70years. In 63 octogenarian patients, survival at 1 and 3years was 97% and 91%, respectively.

Figure 1. Survival of patients discharged following cardiac surgery (n=1844).

Figure 2. Survival of patients discharged following cardiac surgery (n=1844) by age <70 (continuous line) or ≥70 years (broken line).

In patients discharged from hospital (n=1844), the variables associated with mortality in univariate analysis were age, EuroSCORE, history of diabetes mellitus, severely depressed ventricular function (ejection fraction [EF]<30%), preoperative anemia, peripheral arterial disease, and postoperative acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and mechanical ventilation time, and longer ICU and hospital stays. Cox regression analysis showed (Table 4) that age ≥70years, history of severely depressed ventricular function (EF<30%), severe pulmonary hypertension, diabetes mellitus, preoperative anemia, postoperative stroke, and hospitalization associated independently with greater mortality at the end of the follow-up.

Table 4. Cox Regression Analysis Data of Variables Associated With Follow-up Mortality of Patients Discharged From Hospital.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age ≥70 | 2.04 (1.41-2.97) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.6 (1.11-2.3) | .012 |

| Postoperative stroke | 3.23 (1.18-8.81) | .022 |

| Preoperative anemia | 1.74 (1.19-2.55) | .004 |

| Severe pulmonary hypertension | 2.22 (1.3-3.8) | .003 |

| Hospital stay | 1.02 (1.02-1.03) | <.001 |

| Severe ventricular dysfunction (EF <30%) | 2.88 (1.61-5.14) | <.001 |

CI, confidence interval; EF, ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio.

The results of this study show the prognosis of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in our center is highly satisfactory. The study provides important data on mid-term survival in relation to age. By comparison with other Spanish and nonSpanish registries,7, 17, 18, 19, 20 our in-hospital mortality was lower, even among octogenarian patients.8, 21

In-hospital mortality was always lower than that estimated with logistic EuroSCORE, in all age groups. These findings have been described elsewhere by other authors10, 11 and by our group.22, 23 They raise doubts about the value of the model in predicting mortality following cardiac surgery, as it was developed in the 1990s and procedures have changed markedly in the last 10years. Despite this and other limitations described elsewhere,24 the model continues to be used because it is the only one that has been validated in Europe, which enables us to identify high-risk patient groups correctly.25

In patients discharged following surgery, survival was excellent both at 1- and 5-year follow-up. As in other studies, we found no differences attributable to gender.26 Greater late mortality (>3years) associated with cardiac surgery was found in patients aged ≥70. In the group studied at 3 and 5years following discharge, survival was greater than that found in other series.7, 27 Intervention risk profile and surgery type vary from study to study, making comparison difficult. However, our overall results show patients undergoing procedures presented high risk. In the group of octogenarian patients, both in-hospital mortality and end of follow-up mortality (6.3%) were lower than in other series.8, 21, 28, 29

The results presented here are the first obtained in a mid-term follow-up study of morbidity and mortality and survival of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in our hospital. To date, mortality and estimated survival rates are unadjusted and may therefore include all the inherent limitations. In view of this limitation, the next two steps in this prospective study will be, first, to construct adjusted survival models to account for age, gender and other possible confounding factors and second, given the importance of separating mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery from mortality due to competing causes, to estimate relative survival, ie, the ratio between observed survival in the group (considering all-cause deaths) and expected mortality (that which would have been found in the group if this cohort had formed part of the general population and not had the cardiac diseases requiring surgery that were the specific causes of death).30 Relative survival in these patients separates mortality attributable to the studied cardiac disease and cardiac surgery from mortality attributable to the remaining causes of death that can be found in the group.

As reported elsewhere, in isolated coronary surgery, valve replacement surgery, or combined surgery,2, 31, 32, 33 we find that in patients discharged from hospital, independent risk factors associated with greater mid-term mortality were age ≥70years, a history of depressed ventricular function, severe pulmonary hypertension, preoperative anemia, diabetes mellitus, and postoperative stroke. Together with these findings, hospital stay was also an independent predictor of greater mortality. Furthermore, postoperative stroke had an impact on late mortality that differed from the ARCA study results.7 Clearly, advanced age associates with worse mid- and long-term survival34–except when the study population is limited to patients undergoing cardiac surgery and with ≤10days in ICU.31 In studies like this, we frequently find the variables considered possible preoperative risk factors, the type of surgery, and the postoperative complications do not always coincide. This also makes comparison difficult and may explain discrepancies found between studies.

The presence of preoperative anemia (as a dichotomous variable)–defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) as hemoglobin <13g/dl in men and <12g/dl in women–was a risk factor for mid-term mortality. This coincides with a recent study (n=10 025) which, for the first time, shows that preoperative hemoglobin concentration or preoperative anemia–defined according to WHO criteria–are independent risk factors of late mortality (at 5 and 9years) in patients undergoing coronary revascularization surgery.34 It is unclear why these patients have a poorer long-term survival rate. Other variables that frequently associate with long-term survival, such as advanced age, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and renal dysfunction, may act as confounding factors. The etiology of this anemia is not clearly established and we do not know if long-term prognosis improves with treatment.

This study has a number of limitations. Conclusions drawn from an observational study based on results at a single center have a limited application. We think the synergy derived from meticulous cardiac surgery (which is difficult to measure) and well-organized postoperative intensive care in the ICU may explain the low incidence of complications and in-hospital mortality. Full multidisciplinary cooperation exists between the services involved in surgical procedures and surgical indication protocols are strictly observed. Moreover, the most appropriate techniques and preventive measures are used. Another limitation of this study is that we did not establish the same follow-up period for all patients discharged following cardiac surgery. Nor did we determine quality of life at the end of the follow-up, although other studies recently conducted in Spain show patients undergoing cardiac surgery with mid- and long-term survival have good functional capacity and a quality of life equivalent to that of the general Spanish population.7, 8

ConclusionsThis study shows patients undergoing cardiac surgery in our center have a good mid-term prognosis. Age is an important, independent predictor of mortality following cardiac surgery. Other independent predictors of mortality include factors present prior to cardiac surgery–such as depressed ventricular function (EF<30%), severe pulmonary hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and preoperative anemia–and factors that appear following surgery, such as postoperative stroke and longer hospital stay.

FundingThe results presented here are part of a mid- and long-term follow-up study of morbidity and mortality and survival in patients undergoing cardiac surgery that has been partly financed through an agreement between the Balearic Islands Health Service (Servei de Salut de les Illes Balears) and Merck Sharp Dohme de España, S.A.

Conflict of interestsThe authors of this article report the existence of an agreement between the Servei de Salut de les Illes Balears and Merck Sharp Dhome de España, S.A.

Acknowledgements

We thank Silvia Carretero of the Balearic Islands Statistics Office (Institut Balear d’Estadística) for her invaluable help in managing the mortality data.

Received 14 May 2010

Accepted 16 December 2010

Corresponding author: Servicio de Medicina Intensiva, Hospital Universitario Son Dureta, Andrea Doria 55, 07014 Palma, Islas Baleares, Spain. rierasagrera@gmail.com