Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an independent risk factor for mortality in several diseases. However, data published in acute decompensated heart failure (DHF) are contradictory. Our objective was to investigate the impact of AF on mortality in patients admitted to hospital for DHF compared with those admitted for other reasons.

MethodsThis retrospective cohort study included all patients admitted to hospital within a 10-year period due to DHF, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or ischemic stroke (IS), with a median follow-up of 6.2 years.

ResultsWe included 6613 patients (74 ± 11 years; 54.6% male); 2177 with AMI, 2208 with DHF, and 2228 with IS. Crude postdischarge mortality was higher in patients with AF hospitalized for AMI (incident rate ratio, 2.48; P < .001) and IS (incident rate ratio, 1.84; P < .001) than in those without AF. No differences were found in patients with DHF (incident rate ratio, 0.90; P = .12). In adjusted models, AF was not an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality by clinical diagnosis. However, AF emerged as an independent predictor of postdischarge mortality in patients with AMI (HR, 1.494; P = .001) and IS (HR, 1.426; P < .001), but not in patients admitted for DHF (HR, 0.964; P = .603).

ConclusionsAF was as an independent risk factor for postdischarge mortality in patients admitted to hospital for AMI and IS but not in those admitted for DHF.

Keywords

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most frequent sustained cardiac arrhythmia, affects 1% to 2% of the population.1 It is associated with an increased probability of adverse cardiovascular and renal events, as well as overall and cardiovascular mortality.1–3 Most studies indicate AF to be an independent risk factor for mortality in patients without established cardiovascular disease,4 with ischemic heart disease,5 and with cerebrovascular disease.6 However, the available mortality data for patients with AF and heart failure are contradictory.7 Some studies have shown an increased risk of death,8–14 whereas others have found no influence15–21; one study even reported a decreased risk of death.22 There is thus an open debate in the scientific community on whether the relationship between AF and risk of death varies according to the clinical setting or admission diagnosis.

The aim of the present study was to examine the hypothesis that the presence of AF is associated with an adverse vital prognosis–both during hospitalization and after discharge–in patients admitted for decompensated heart failure (DHF), stroke, or acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

METHODSStudy PopulationFrom January 2000 to December 2009, a 10-year period, we retrospectively recruited all individuals with a principal discharge diagnosis of DHF (International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, codes: 428.0, 428.1, 428.20, 428.21, 428.22, 428.23, 428.30, 428.31, 428.32, 428.33, 428.41, 428.43, 428.9), included in the INCA study,23 AMI (410.01, 410.10, 410.11, 410.12, 410.21, 410.31, 410.41, 410.51, 410.70, 410.71, 410.72, 410.81, 410.82, 410.91), included in the CASTUO study,24 and stroke (433.0, 433.01, 433.10, 433.11, 433.21, 433.30, 434.00, 434.01, 434.10, 434.11, 434.90, 434.91, 436), included in the ICTUS study25 and who were consecutively admitted to the district hospital. For the present analysis, we selected the 3 diagnoses (DHF, stroke, and AMI) constituting the most frequent causes of admission for cardiovascular disease.26,27 The information sources were the hospital coding service and the Spanish National Death Index. Mortality data were obtained from this index in 2011 for 100% of patients. This study was approved by the appropriate ethics committee. The only patients excluded were those with DHF who also had severe mitral or aortic valve disease.

Atrial fibrillation diagnosed via an electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission or during hospitalization meeting the following characteristics: irregular R-R interval, absence of P waves, and variable atrial cycle length. Atrial fibrillation was considered present if it was noted as a secondary diagnosis in the discharge sheet–independently of the type or time of onset–and was additionally confirmed in the discharge ECG report. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as the presence of a glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for at least 3 months or its previous diagnosis in the medical records. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was considered to be present in patients with a previous diagnosis of emphysema or chronic bronchitis. Peripheral arterial disease was considered to be present if it was previously diagnosed in patients’ medical records. The main study variables were in-hospital and postdischarge all-cause mortality. The median postdischarge follow-up was 6.2 years (interquartile range, 3.9-8.8).

Statistical AnalysisVariables associated with in-hospital all-cause mortality were studied using relative risk (RR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) in a binary logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, active smoking, history of stroke, COPD, CKD, and peripheral arterial disease, and discharge diagnosis. In addition, model calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and discrimination using the C statistic. Variables associated with postdischarge all-cause mortality were studied using hazard ratios (HRs) in a Cox regression model adjusted for various risk factors (age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, active smoking, history of stroke, COPD, CKD, and peripheral arterial disease, and discharge diagnosis). HRs are presented with their corresponding 95%CIs. The “Enter” method was chosen in both models. In addition, in the hierarchical model, the first-degree interaction between AF and discharge diagnosis (DHF, AMI, or stroke) was studied using likelihood ratio statistics and the backward elimination method (chunk test). The proportional hazards assumption was tested for the analyses. The incidence rates were calculated with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and were estimated using the !COI V 2008.02.29 JM Domenech macro (Autonomous University of Barcelona). The distributions were compared between the groups using the log-rank test. SPSS version 20 statistical software (IBM, United States) was used for the analyses.

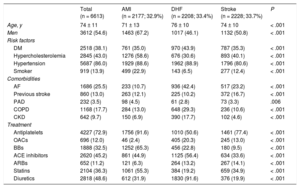

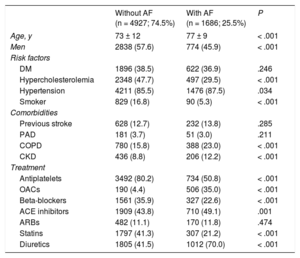

RESULTSStudy Population and Baseline CharacteristicsThe study population included 6613 patients (2177 with AMI, 2208 with DHF, and 2228 with stroke) with a mean age of 73.3 years. In total, 1686 patients (25.5%) had AF. Atrial fibrillation was significantly more common in patients with DHF than in those with AMI or stroke. The baseline characteristics of the sample according to discharge diagnosis are shown in Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the patients diagnosed with AF vs those without AF are shown in Table 2. Patients with AF were older and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities (hypertension, COPD, and CKD).

Patients’ Baseline Characteristics According to Discharge Diagnosis

| Total (n = 6613) | AMI (n = 2177; 32.9%) | DHF (n = 2208; 33.4%) | Stroke (n = 2228; 33.7%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 74 ± 11 | 71 ± 13 | 76 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | < .001 |

| Men | 3612 (54.6) | 1463 (67.2) | 1017 (46.1) | 1132 (50.8) | < .001 |

| Risk factors | |||||

| DM | 2518 (38.1) | 761 (35.0) | 970 (43.9) | 787 (35.3) | < .001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 2845 (43.0) | 1276 (58.6) | 676 (30.6) | 893 (40.1) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 5687 (86.0) | 1929 (88.6) | 1962 (88.9) | 1796 (80.6) | < .001 |

| Smoker | 919 (13.9) | 499 (22.9) | 143 (6.5) | 277 (12.4) | < .001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| AF | 1686 (25.5) | 233 (10.7) | 936 (42.4) | 517 (23.2) | < .001 |

| Previous stroke | 860 (13.0) | 263 (12.1) | 225 (10.2) | 372 (16.7) | < .001 |

| PAD | 232 (3.5) | 98 (4.5) | 61 (2.8) | 73 (3.3) | .006 |

| COPD | 1168 (17.7) | 284 (13.0) | 648 (29.3) | 236 (10.6) | < .001 |

| CKD | 642 (9.7) | 150 (6.9) | 390 (17.7) | 102 (4.6) | < .001 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Antiplatelets | 4227 (72.9) | 1756 (91.6) | 1010 (50.6) | 1461 (77.4) | < .001 |

| OACs | 696 (12.0) | 46 (2.4) | 405 (20.3) | 245 (13.0) | < .001 |

| BBs | 1888 (32.5) | 1252 (65.3) | 456 (22.8) | 180 (9.5) | < .001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 2620 (45.2) | 861 (44.9) | 1125 (56.4) | 634 (33.6) | < .001 |

| ARBs | 652 (11.2) | 121 (6.3) | 264 (13.2) | 267 (14.1) | < .001 |

| Statins | 2104 (36.3) | 1061 (55.3) | 384 (19.2) | 659 (34.9) | < .001 |

| Diuretics | 2818 (48.6) | 612 (31.9) | 1830 (91.6) | 376 (19.9) | < .001 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BBs, beta-blockers; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHF, decompensated heart failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; OACs, oral anticoagulants; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Values represent No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Patients’ Baseline Characteristics According to the Presence of Atrial Fibrillation

| Without AF (n = 4927; 74.5%) | With AF (n = 1686; 25.5%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 73 ± 12 | 77 ± 9 | < .001 |

| Men | 2838 (57.6) | 774 (45.9) | < .001 |

| Risk factors | |||

| DM | 1896 (38.5) | 622 (36.9) | .246 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 2348 (47.7) | 497 (29.5) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 4211 (85.5) | 1476 (87.5) | .034 |

| Smoker | 829 (16.8) | 90 (5.3) | < .001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Previous stroke | 628 (12.7) | 232 (13.8) | .285 |

| PAD | 181 (3.7) | 51 (3.0) | .211 |

| COPD | 780 (15.8) | 388 (23.0) | < .001 |

| CKD | 436 (8.8) | 206 (12.2) | < .001 |

| Treatment | |||

| Antiplatelets | 3492 (80.2) | 734 (50.8) | < .001 |

| OACs | 190 (4.4) | 506 (35.0) | < .001 |

| Beta-blockers | 1561 (35.9) | 327 (22.6) | < .001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 1909 (43.8) | 710 (49.1) | .001 |

| ARBs | 482 (11.1) | 170 (11.8) | .474 |

| Statins | 1797 (41.3) | 307 (21.2) | < .001 |

| Diuretics | 1805 (41.5) | 1012 (70.0) | < .001 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; OACs, oral anticoagulants; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Values represent No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

There were 819 deaths (12.4%). Patients who died during hospitalization were significantly (all P < .05) older (79 ± 9 years vs 73 ± 11 years) and more likely to be female and have AF (29.6% vs 24.9%), COPD (20.4% vs 17.3%), and CKD (14.3% vs 9.1%). However, they had a significantly lower prevalence of hypercholesterolemia (18.7% vs 46.4%) and active smoking (6.9% vs 14.9%).

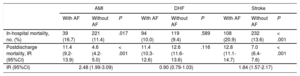

In-hospital mortality was higher in patients with AF than in those without this condition (241 [14.3%] vs 572 [11.6%]; P < .001). After stratification according to discharge diagnosis (Table 3), in-hospital mortality was higher in patients admitted for AMI who had AF vs those who did not have AF (16.7% vs 11.4%; P = .017) and in patients admitted for stroke who had AF vs those who did not (20.9% vs 13.6%; P < .001); in contrast, no significant difference was seen in those admitted for DHF (10.0% vs 9.4%; P = .589).

In-hospital and Postdischarge Mortality According to Admission Diagnosis and the Presence of Atrial Fibrillation

| AMI | DHF | Stroke | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With AF | Without AF | P | With AF | Without AF | P | With AF | Without AF | P | |

| In-hospital mortality, no. (%) | 39 (16.7) | 221 (11.4) | .017 | 94 (10.0) | 119 (9.4) | .589 | 108 (20.9) | 232 (13.6) | < .001 |

| Postdischarge mortality, IR (95%CI) | 11.4 (9.2-13.9) | 4.6 (4.2-5.0) | < .001 | 11.4 (10.3-12.6) | 12.6 (11.6-13.6) | .116 | 12.8 (11.1-14.7) | 7.0 (6.4-7.6) | < .001 |

| IR (95%CI) | 2.48 (1.99-3.09) | 0.90 (0.79-1.03) | 1.84 (1.57-2.17) | ||||||

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DHF, decompensated heart failure; IR, incidence rate per 100 person-years.

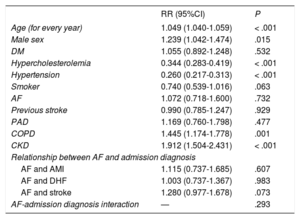

In a well-calibrated adjusted model with high discriminatory power (Table 4), AF was not an independent predictor of mortality (adjusted RR = 1.072; P = .732) in the total cohort or according to discharge diagnosis (AMI: adjusted RR = 1.115; P = .607; DHF: adjusted RR = 1.003; P = .983; stroke: adjusted RR = 1.280; P = .073). There was no significant interaction.

Regression Model for In-hospital Mortality

| RR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (for every year) | 1.049 (1.040-1.059) | < .001 |

| Male sex | 1.239 (1.042-1.474) | .015 |

| DM | 1.055 (0.892-1.248) | .532 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.344 (0.283-0.419) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 0.260 (0.217-0.313) | < .001 |

| Smoker | 0.740 (0.539-1.016) | .063 |

| AF | 1.072 (0.718-1.600) | .732 |

| Previous stroke | 0.990 (0.785-1.247) | .929 |

| PAD | 1.169 (0.760-1.798) | .477 |

| COPD | 1.445 (1.174-1.778) | .001 |

| CKD | 1.912 (1.504-2.431) | < .001 |

| Relationship between AF and admission diagnosis | ||

| AF and AMI | 1.115 (0.737-1.685) | .607 |

| AF and DHF | 1.003 (0.737-1.367) | .983 |

| AF and stroke | 1.280 (0.977-1.678) | .073 |

| AF-admission diagnosis interaction | — | .293 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AF, atrial fibrillation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHF, decompensated heart failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; RR, relative risk.

Specifications of model:: chi-square = 12.715; P = .122. C statistic = 0.769; P < .001.

Patients who died during postdischarge follow-up were significantly (all P < .05) older (77 ± 9 years vs 71 ± 12 years) and more likely to be male and have diabetes mellitus (44.5% vs 34.6%), AF (31.0% vs 21.1%), stroke (14.1% vs 12.2%), peripheral arterial disease (5.2% vs 2.4%), COPD (24.5% vs 12.7%), and CKD (14.3% vs 5.7%). However, they had a significantly lower proportion of hypercholesterolemia (35.5% vs 53.4%) and active smoking (9.6% vs 18.2%).

The postdischarge mortality incidence rate was 11.9 (95%CI, 11.0-12.8) per 100 patient-years for patients with AF vs 7.1 (95%CI, 6.8-7.5) for those without AF, giving an incidence rate ratio of 1.66 (95%CI, 1.52-1.82; P < .001). After stratification according to discharge diagnosis (Table 3), patient mortality was higher in those admitted for AMI who had AF than in those who did not have AF (incidence rate of 11.4 vs 4.6 per 100 person-years; P < .001) and in those admitted for stroke who had AF than in those who did not (incidence rate of 12.8 vs 7.0 per 100 person-years; P < .001); there was no significant difference for those admitted for DHF (11.4 vs 12.6; P = .116).

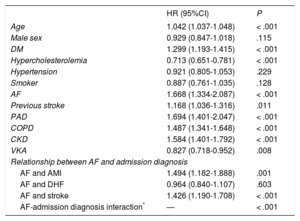

In the adjusted model (Table 5), AF was an independent predictor of mortality (adjusted HR, 1.668; P < .001) in the total cohort, as well as in patients admitted for AMI (adjusted HR, 1.494; P = .001) or stroke (adjusted HR, 1.426; P < .001). However, there was no significant difference in patients admitted for DHF (adjusted HR, 0.964; P = .603), indicating a highly significant interaction. A model that also included the complete medical treatment until discharge showed no differences from that shown in Table 5 (data not shown). In the subgroup of patients with DHF whose left ventricular ejection fraction was known (n = 805), there was no significant interaction between AF and ejection fraction (P for interaction = .331) in terms of mortality.

Cox Regression Model for Postdischarge Mortality

| HR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.042 (1.037-1.048) | < .001 |

| Male sex | 0.929 (0.847-1.018) | .115 |

| DM | 1.299 (1.193-1.415) | < .001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.713 (0.651-0.781) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 0.921 (0.805-1.053) | .229 |

| Smoker | 0.887 (0.761-1.035) | .128 |

| AF | 1.668 (1.334-2.087) | < .001 |

| Previous stroke | 1.168 (1.036-1.316) | .011 |

| PAD | 1.694 (1.401-2.047) | < .001 |

| COPD | 1.487 (1.341-1.648) | < .001 |

| CKD | 1.584 (1.401-1.792) | < .001 |

| VKA | 0.827 (0.718-0.952) | .008 |

| Relationship between AF and admission diagnosis | ||

| AF and AMI | 1.494 (1.182-1.888) | .001 |

| AF and DHF | 0.964 (0.840-1.107) | .603 |

| AF and stroke | 1.426 (1.190-1.708) | < .001 |

| AF-admission diagnosis interaction* | — | < .001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHF, decompensated heart failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

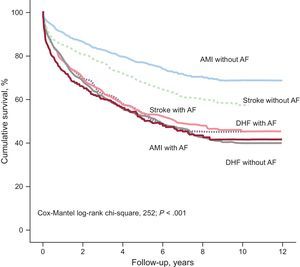

Figure presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curve and shows that patients with a more unfavorable clinical course (with significant overlap in clinical course among the groups) were those with DHF (independently of AF presence), as well as those with AMI and AF or stroke and AF (log-rank test, P < .001). In contrast, the patients with a significantly more favorable clinical course were (in order) those with AMI without AF and those admitted for stroke without AF.

DISCUSSIONOur results show that AF is an independent risk factor for mid-to-long–term mortality in patients admitted for AMI and stroke; no influence on mortality was seen in patients admitted for DHF.

Decompensated heart failure and AF share multiple risk factors and both can be associated with most types of structural heart disease. Up to 20% of patients with AF have DHF and between 5% and 50% of patients with DHF have AF at some time in their clinical course.28 In addition, similar to DHF, the prevalence of AF increases with age29 and as patients’ functional class worsens.30 According to the ADHERE registry,31 up to 30% of patients admitted for DHF have AF. Thus, there is an intimate and complex interrelationship between DHF and AF.32,33

The prognostic impact of AF in patients with DHF continues to be a source of controversy. In the SOLVD study,8 AF was an independent predictor of mortality. The CHARM,34 DIG,9 and DIAMOND7 trials also found this association. However, in the V-HEFT study,21 AF was not associated with an increased risk of death. In the subsequent COMET study,35 the presence of AF in a well-adjusted model provided no independent prognostic information. In contrast to the present study, the populations included in these clinical trials were generally younger and had less comorbidity; additionally, women were underrepresented and had better prognosis. In a subsequent meta-analysis14 including 6 observational studies, there was no independent impact of AF on prognosis in 4 studies.36–39 The authors of this meta-analysis concluded that the presence of AF was associated with an adverse prognosis and considered that the disagreements among studies could be explained by an incomplete adjustment for comorbidities associated with AF or the risk of adverse outcomes specifically related to new-onset AF. Notably, due to the design of our study, which necessitated the presence of AF as secondary diagnosis and in the discharge ECG report, most forms of AF were persistent or permanent.

In contrast, in the study by Pai and Varadarajan,40 the presence of AF was a risk factor (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.01-1.25). There are important differences between that study and the present study because our patients were older (difference in mean ages of 10 years) and follow-up was significantly longer (mean, 6.5 vs 2.5 years). In addition, we performed a carefully adjusted multivariable analysis, whereas the analysis in the study by Pai and Varadarajan40 was only partially adjusted for age and left ventricular ejection fraction. Finally, our study included patients admitted for heart failure, whereas Pai and Varadarajan40 considered stable patients who underwent a routine echocardiographic examination. In the study by Ahmed et al.,41 performed in patients admitted for DHF, the presence of AF was an independent risk factor for mortality (adjusted HR, 1.52; 95%CI, 1.11-2.07). Once again, there were marked differences in the study compositions. The study by Ahmed et al.41 included a low proportion of hypertensive (18% vs 89%) and diabetic (26% vs 44%) patients and 18% were African-American (not represented in our registry). In the present study, there were no differences in the relationship between AF and mortality after an additional adjustment for medical treatment for DHF (data not shown).

The debate continues about whether AF is a simple observer or bystander in patients with DHF.42 Here, AF was not an independent risk factor for either in-hospital or mid-term postdischarge mortality. It may be that the lack of continuous monitoring or serial ECG could mean that paroxysmal AF is often missed–a potential classification bias–and it is unclear what impact this would have on the results. In addition, as reported by Wasywich et al.,43 adjustment for the main comorbidities (stroke, peripheral arterial disease, COPD, and CKD) has eliminated the potential residual bias and, thus, the possibility of paroxysmal AF emerging as an independent risk factor.

In the current study, the presence of AF in patients with previous AMI and stroke was a risk factor for mortality. These findings are consistent with previous results. In the study by Kundu et al.,44 AF onset during hospitalization for AMI–in a well-adjusted model–was associated with increased risk of stroke, DHF, cardiogenic shock, mortality, and readmission. Similarly, in the TRACE study,5 AF onset after AMI was independently associated with an increased risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality.

In addition, in a study performed by Jørgensen et al.45 in patients admitted for stroke, the presence of AF (in an adjusted model) was associated with increased stroke lesion size, as well as cortical involvement, longer hospital stay, and increased mortality. Similar data were obtained in the study by Lin et al.,6 with AF associated with increased short- and long-term mortality.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, during the prolonged study recruitment period, there were important changes in the treatment recommendations that could have influenced the findings. Second, given the retrospective study design, it was not possible to characterize the type of AF or its time of onset. Third, there was no information on left ventricular ejection fraction in more than half of patients and a significant proportion of patients lacked information on DHF etiology. However, due to its large sample size, this study afforded an excellent opportunity to explore the hypothesis of a differential effect of AF on mortality. Fourth, 35% of patients with AF included in this study received anticoagulants. This figure, although suboptimal, is in line with that of other studies highlighting the global problem of undertreatment with anticoagulants.46 In addition, given that our study covers a 10-year period, it must be remembered that this percentage represents a mean. There was a growing trend for anticoagulant prescription (first 2 years vs last 2 years: 26.6% vs 41.4%; P for trend < .001). Finally, because this study is based on a single-center registry conducted in a secondary hospital, the results might not be generalizable to the entire health care system.

CONCLUSIONSAtrial fibrillation is a frequent condition in patients hospitalized for AMI, DHF, and stroke. Its presence is associated with worse prognosis, both during hospitalization and after discharge, in patients with AMI and stroke, and it additionally acts as an independent risk factor for postdischarge mortality in these patients. A significant interaction was seen in patients with DHF because AF no longer discriminated patients with worse vital prognosis.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Atrial fibrillation is the most frequent sustained arrhythmia and growing evidence indicates that it is an independent risk factor for mortality in both healthy populations and those with diverse cardiovascular conditions. However, its prognostic influence on heart failure continues to be controversial. Its recognition as an independent prognostic factor might be relevant and have clinical implications in various settings, such as the development of aggressive rhythm control strategies.

- –

This is the first work to show a differential effect of AF on postdischarge mortality among the 3 main causes of cardiovascular admission in Spain (AMI, heart failure, and stroke) by comparing 3 cohorts of consecutive patients admitted to a secondary hospital. Atrial fibrillation, predominantly in its persistent/permanent form, was an independent risk factor for mid-to-long–term mortality in patients with AMI and stroke, but not in those with heart failure.

We thank Paula Álvarez-Palacios, Gema Cebrián, and María-José Jiménez for their invaluable help.