The relationship between myocardial bridging and symptoms is still unclear. The purpose of our study was to assess the relationship between myocardial bridging detected by multidetector computed tomography and symptoms in a patient population with chest pain syndrome.

MethodsThe study enrolled 393 consecutive patients without previous coronary artery disease studied for chest pain and referred to multidetector computed tomography between January 2007 and December 2010. Noninvasive coronary angiography was performed using multidetector computed tomography. Myocardial bridging was defined as part of a coronary artery completely surrounded by myocardium on axial and multiplanar reformatted images.

ResultsMean age was 64.6 (12.4) years and 44.8% were male. Multidetector computed tomography detected 86 myocardial bridging images in 82 of the 393 patients (20.9%). Left anterior descending was the most frequent coronary artery involved (87.2%). The prevalence of myocardial bridging was significantly higher in patients without significant atherosclerotic coronary stenosis on multidetector computed tomography (24.9% vs 15.0%; P=.02). Patients with myocardial bridging were younger (60.3 [13.8] vs 65.8 [11.9]; P<.001), had less prevalence of hyperlipidemia (29.3% vs 41.8%; P=.03), and more prevalence of cardiomyopathy (6.1% vs 1.6%; P=.02) compared with patients without myocardial bridging on multidetector computed tomography.

ConclusionsMultidetector computed tomography is an easy and reliable tool for comprehensive in vivo diagnosis of myocardial bridging. The results of the present study suggest myocardial bridging is the cause of chest pain in a subgroup of younger aged patients with less prevalence of hyperlipidemia and more prevalence of cardiomyopathy than patients with significant atherosclerotic coronary artery disease on multidetector computed tomography.

Keywords

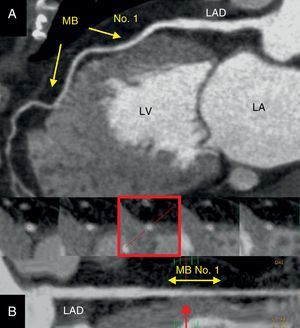

Myocardial bridging (MB) is defined as a segment of a major epicardial coronary artery that proceeds intramurally through the myocardium beneath the muscle bridge. It can cause variable degrees of systolic obstruction. The left anterior descending coronary artery is the vessel involved in the majority of cases. The incidence of MB varies substantially between angiographic series in the general population (0.5%-4.5%)1, 2, 3 and autopsy specimens (15%-85%).4, 5 Although MB is usually asymptomatic and has a favorable long-term outcome,6 this anomaly has been associated with various clinical manifestations such as unstable angina, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and sudden death.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 However, association between ischemic symptoms and MB has been inconsistently reported and is still unclear. Clinical consequences of MB are difficult to evaluate and opinion remains divided as to whether MB has pathological consequences or is merely an epiphenomenon. Large clinical databases are required to justify the link between clinical signs or symptoms and MB as the primary culprit and move beyond the current empirical approach to the clinical management of this frequent coronary anomaly. Invasive coronary angiography is the gold standard for MB detection, but it is invasive and may not be sensitive enough to detect a thin bridge. Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is a noninvasive technique with the advantages of vessel wall and plaque depiction in addition to its ability to assess the luminal diameter, course, and anatomic relationship of the coronary arteries.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Therefore, it offers a unique opportunity to evaluate the real incidence, location, and morphology of MB in an in vivo setting (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Demonstrative case of a 65-year-old female patient with normal coronary artery and intramyocardial bridging assessed by multidetector computed tomography. A: Multiplanar reformatted postprocessing with maximal intensity pixel visualization of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Two segments of the left anterior descending coronary artery were evolved with both myocardial bridges; one more proximal (no. 1) and another more distal (arrows). B: Curved multiplanar reformatting depicting the proximal and middle left anterior descending coronary artery along its major axis. At the bottom, cross-sectional images of the segment evolved by the proximal myocardial bridge no. 1 (yellow double arrow). Note how the proximal section (left) is full encased into the epicardial fat, in contrast with the near full myocardial encasement (red arrow and frame) of the myocardial bridge no. 1 (20mm, length and 3mm, depth). LA, left atrium; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LV, left ventricle. MB, myocardial bridging.

The purpose of our study was to assess the relationship between MB and symptoms in a patient population without history of coronary artery disease and studied for chest pain using MDCT. We also compared the clinical characteristics between subjects with and without MB.

Methods Study Design and PatientsBetween January 2007 and December 2010, 393 consecutive patients studied for chest pain and referred to MDCT for suspected coronary artery disease were enrolled. Demographic and clinical characteristics including age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking status), kidney failure, peripheral artery disease, prior cardiomyopathy, and prior valvulopathy were identified. Diabetes was defined as fasting blood glucose>126mg/dL or treatment with antidiabetic medications. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure>140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure>90mmHg (or both) or current treatment for hypertension. Hyperlipidemia was defined as total cholesterol>200mg/dL or concurrent treatment for such. Kidney failure was defined as a serum creatinine level of more than 1.3mg/dL (115μmol/L). Patients with atrial fibrillation, significant renal failure, or history of significant iodinated contrast allergy were excluded. In addition, we excluded those with a previously documented history of obstructive coronary artery disease. All patients gave written informed consent for MDCT in accordance with a protocol approved by the institutional review board. The decision to perform MDCT was taken by the patient's physician in all cases, based on age, risk, and severity or persistence of symptoms. The study population was divided into 2 groups according to the presence of significant coronary stenosis on MDCT.

Multidetector Computed Tomography AcquisitionsNoninvasive coronary angiography was performed using Brilliance™ 64 MDCT (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands). Before MDCT examination, heart rate (HR) and blood pressure were monitored. In the absence of contraindications, subjects received propranolol (5-15mg intravenously) if the resting HR exceeded 65 bpm. All subjects were in sinus rhythm. The HR of all subjects ranged between 48 bpm and 70 bpm (average, 60 [7.5] bpm) with or without premedication. The subjects were imaged in the supine position. The subjects were instructed to maintain an inspiratory breath-hold during which the MDCT data and electrocardiogram (ECG) trace were acquired. Scanning was performed from the tracheal bifurcation to 1cm below the diaphragmatic face of the heart. After a scout scan a volume of 80mL to 120mL of contrast media (iopamidol 370mgI/mL, Bracco) was injected intravenously via an 18G catheter placed in the antecubital vein, at a rate of 4mL/s to 5mL/s and controlled with a bolus-tracking technique, followed by a bolus of 40mL of saline. Scanning started automatically with a delay of 5s after a predefined threshold of 140 HU was reached in the ascending aorta. Scanning was performed at 120kV, with an effective tube current of 600mA to 1000mA, slice collimation of 64×0.625mm acquisition, gantry rotation time of 0.4 s, and pitch of 0.2. Image reconstruction was done routinely using the retrospective ECG-gating method. Data sets were acquired at phases of 40% and 75% of the RR cycle. The effective dose of MDCT was estimated from the dose–length product and an organ-weighing factor [k= 0.014 mSv×(mGy×cm)−1] for the chest as the investigated anatomical region.19

Image Processing and AnalysisAnalysis of scans was performed on a dedicated workstation (Philips Extended Brilliance Workspace) for all 15 coronary artery segments defined according to the guidelines of the American Heart Association.20 For each study, a calcium score was determined using the methods of Agatston et al.21 Coronary calcium score was measured without contrast using semiautomatic software (HeartBeat CS, Philips Medical Systems) that displayed colored spots for calcium to be manually marked by the operator and automatically calculated all spots to a summed calcium score. Contrast-enhanced MDCTs were examined for presence of MB in all available segments using the original axial slices, multiplanar and curved planar reformations in at least two planes, one parallel and one perpendicular to the course of the vessel. Thin-slab maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstructions and volume-rendered images were also performed. Scans were analyzed by a consensus of an experienced radiologist and a cardiologist, who were both blinded to the clinical history. Discrepancies were resolved after additional joint review and discussion. Image quality of each coronary artery segment was classified by both observers as being diagnostic (no or moderate artifacts, acceptable for evaluation) or not evaluable (severe artifacts impairing evaluation). MB was defined as part of a coronary artery completely surrounded by myocardium on axial and multiplanar reformatted images. The location of the tunneled segment was noted, and the length and depth of the segment were measured. The depth of MB was determined by perpendicular measurement of the thickness of overlying muscle with use of the short-axis image in which overlying muscle was seen to be thickest. Each segment was assessed for the presence of atherosclerotic changes (calcified and noncalcified plaque). Contrast-enhanced MDCTs were examined for presence of obstructive coronary luminal narrowing in all coronary segments. Significant coronary stenoses were defined as greater than 50% reduction of the lumen diameter.

Statistical AnalysisAll statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States). Continuous variables are presented as mean (standard deviation). Categorical data were presented with absolute frequencies and percentages. Differences between groups were analyzed using the Student t test for continuous variables or the chi-square test for categorical variables. Two-tailed P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results Patient DataMean age was 64.6 (12.4) years and 44.8% were male. Table 1 shows the demographics and baseline characteristics of the population. All MDCT examinations were performed without complications. Image quality was good, and all involved segments were considered to be assessable. A normal pattern of epicardial coronary artery or the presence of an intramuscular segment could be identified clearly both on axial views and on multiplanar reformatted images. The estimated average effective radiation exposure was 1.2 (0.2) mSv for calcium scoring and 12.4 (5.1) mSv for noninvasive coronary angiography.

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of the Population. Differences Between Patients With and Without Significant Coronary Artery Stenosis on Multidetector Computed Tomography

| Overall (n=393) | Significant coronary artery stenosis on MDCT (n=160) | No significant coronary artery stenosis on MDCT (n=233) | P | |

| Mean age, years | 64.6±12.5 | 69.6±9.5 | 61.1±13.7 | <.001 |

| Sex (Male) | 176 (44.8) | 87 (54.4) | 89 (38.2) | .002 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.6±4.9 | 28.6±3.6 | 27.4±5.2 | .190 |

| Hypertension | 211 (53.7) | 104 (65) | 107 (45.9) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 84 (21.4) | 45 (28.1) | 39 (16.7) | .007 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 154 (39.2) | 66 (41.3) | 88 (37.8) | .480 |

| Current smoking | 66 (16.8) | 25 (15.6) | 41 (17.6) | .600 |

| Kidney failure | 6 (1.5) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (1.7) | .710 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 9 (2.3) | 6 (3.8) | 3 (1.3) | .110 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 10 (2.5) | 5 (3.1) | 5 (2.1) | .530 |

| Valvulopathy | 10 (2.5) | 7 (4.4) | 3 (1.3) | .060 |

| Calcium score | 274±616.4 | 536.4±776.1 | 110.2±416.4 | <.001 |

| Myocardial bridge | 82 (20.9) | 24 (15) | 58 (24.9) | .020 |

BMI, body mass index; MDCT, multidetector computed tomography.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or no. (%).

The MDCT detected 86 MB in 82 patients (20.9%) of the 393 subjects. The coronary arteries involved are presented in Table 2. Most were located in mid left anterior descending coronary artery (87.2%) followed by intermediate artery (4.7%). Single-site involvement was found in 79 patients. Three patients had more than one coronary artery involved: left anterior descending and intermediate artery (patient 1); left anterior descending, right coronary, and obtuse marginal artery (patient 2); left anterior descending and obtuse marginal artery (patient 3). The overall mean length and maximum myocardial thickness overlying the bridge (depth) were 20.5 (5.2)mm (range, 8–29mm) and 2.3 (0.7)mm (range, 1–3.3mm), respectively. In all cases, the intramuscular segment could also be identified on volume-rendering reformations, allowing a 3-dimensional anatomical evaluation of its location.

Table 2. Location and Incidence of Myocardial Bridge in the Coronary Arteries

| Coronary artery | Myocardial bridge (n=86) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 75 (87.2) |

| Intermediate artery | 4 (4.7) |

| Diagonal branches | 3 (3.5) |

| Obtuse marginal artery | 3 (3.5) |

| Right coronary artery | 1 (1.1) |

Data are expressed as no. (%).

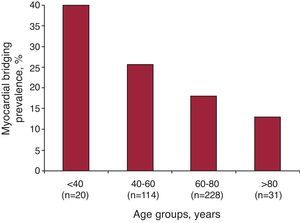

Table 1 shows characteristics of the population as a function of the presence of significant coronary artery stenosis on MDCT. The prevalence of MB was significantly higher in patients without significant coronary stenosis on MDCT (24.9% vs 15.0%; P=.02). Patients were also classified in 2 groups based on the presence of MB. Table 3 shows the demographics characteristics of the 2 groups based on the presence of MB. Patients with MB were younger (60.3 [13.8] vs 65.8 [11.9]; P<.001), with less prevalence of hyperlipidemia (29.3% vs 41.8%; P=.03) and more prevalence of cardiomyopathy (6.1% vs 1.6%; P=.02) compared with patients without MB on MDCT. Prevalence of MB by age groups is shown in Figure 2. Cardiomyopathies in the group without MB were idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in 4 cases and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 1 case; while in MB group had idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in 3 cases and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 2 cases.

Table 3. Differences in Clinical Characteristics Between Patients With and Without Myocardial Bridging

| MB group(n=82) | Non-MB group(n=311) | P | |

| Age, years | 60.3±13.8 | 65.8±11.9 | <.001 |

| Male | 40 (48.8) | 136 (43.7) | .41 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.5 (4.1) | 27.9 (5.1) | .20 |

| Hypertension | 44 (53.7) | 167 (53.7) | .99 |

| Diabetes | 16 (19.5) | 68 (21.9) | .64 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 24 (29.3) | 130 (41.8) | .03 |

| Current smoking | 10 (12.2) | 56 (18) | .21 |

| Kidney failure | 0 (0) | 6 (1.9) | .20 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2 (2.4) | 7 (2.3) | .91 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 5 (6.1) | 5 (1.6) | .02 |

| Valvulopathy | 3 (3.7) | 7 (2.3) | .47 |

| Significant coronary artery stenosis on MDCT | 24 (29.3) | 136 (43.7) | .023 |

BMI, body mass index; MB, myocardial bridging, MDCT, multidetector computed tomography.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or no. (%).

Figure 2. Prevalence of myocardial bridging by age groups.

DiscussionThis study shows that MDCT is an easy and reliable tool for comprehensive in vivo diagnosis of the intramuscular course of coronary arteries. The incidence of MB in our study was 20.9%, mainly involving left anterior descending coronary artery in concordance with previous reports.22, 23 Our data suggest MB is the likely cause of chest pain in a subgroup of younger patients and with less prevalence of hyperlipidemia than patients with significant coronary stenosis on MDCT. Furthermore a higher prevalence of prior cardiomyopathy was found in MB group, in concordance with previous studies.24

Typically, the coronary arteries are epicardial in location, running on the surface of the myocardium. MB seems to be a congenital anomaly, apparently due to incomplete exteriorization of the primitive coronary intratrabecular arterial network. It was first described in 1737, when Reyman noted this particular anatomy in human hearts.25 In 1961, Polacek was the first person to use the term myocardial bridge.26 With the development and increasing frequency of coronary angiography, an increasing interest in this entity developed. Clinical consequences of MB are difficult to evaluate, and considering the presence of MB as a cause of myocardial ischemia remains ambiguous. Normally only 15% of coronary blood flow occurs during systole, and because MB is a systolic event on angiography its clinical significance and relevance have been questioned. Usually, MB is a benign congenital condition with a favorable long-term outcome. Nevertheless, cases have been reported of MB as the sole abnormality on angiography in patients with angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, left ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 However, considering the prevalence of MB these complications are rare and objective signs of ischemia cannot always be demonstrated. Resting ECGs are frequently normal; stress testing may induce nonspecific signs of ischemia.6, 27 Perfusion defects may be seen on myocardial scintigraphy28 but are not obligatory even in deep bridges with significant systolic compression or after vasoactive stimulation.27, 29 Although this malformation is present at birth, symptoms usually do not appear before the third decade. Nor is there a clear relationship between symptoms and the length of the tunneled segment or the degree of systolic compression. Several studies have not demonstrated that bridging causes critical stenosis.30, 31, 32 Therefore bridging may be an incidental finding in patients without another cardiac explanation for chest pain. To our knowledge, no study to date confirmed a statistically significant relationship between MB and symptoms in a patient population with chest pain syndrome.

Until now the gold standard for diagnosing MB was coronary angiography with the characteristic “milking effect” induced by systolic compression of the tunneled segment. However, it is commonly recognized conventional coronary angiography underestimates the prevalence of MB by delivering a visualization that is limited to the vessel lumen and thus necessitating that investigators rely on indirect signs which are rather insensitive in shallow variants of MB that demonstrate only minimal or no systolic compression.4 In patients with thin bridges, the milking effect may be missed and new imaging techniques and provocation tests may be required.33, 34, 35 At variance with conventional invasive coronary angiography, MDCT enables visualization not only of the lumen of coronary arteries but also their walls, the neighboring myocardium, and the heart chambers in any plane, and thus allows the depiction of tunneled segments even when there is only minimal or no systolic compression and no change in vessel course.36, 37, 38 Therefore MDCT should be able to visualize MB in a more sensitive and comprehensive way than coronary angiography, in which the diagnosis is made by the indirect finding of systolic compression of the coronary artery indicated by the milking effect. Furthermore multiplanar reformatted images assessed by MDCT provide the thicknesses and directions of muscle bundles in the MB. Preoperative knowledge of MB, as detected on MDCT, may theoretically help surgeons to avoid complications during coronary surgery, including perforation of the ventricular wall during attempts of isolation of the intramuscular artery.39, 40 In addition MDCT is able to delineate calcified and noncalcified lesions that do not cause luminal stenosis within the coronary artery wall.41, 42 The prevalence of MB reported in MDCT coronary angiographic series has ranged from 3.5% to 30.5% in patients with chest pain or with suspected or known coronary artery disease.22, 23 Based on our data MDCT may become a useful tool in patients with angina-like symptoms or established ischemia but at low risk of coronary artery disease, because MDCT enables not only the diagnosis of obstructive coronary artery disease but also MB detection, which is a common cause of chest pain in this subgroup of patients.

Study LimitationsThe present study has certain limitations. It is a descriptive study of retrospective nature in a single center. We didn’t exclude patients with any other risk factors causing chest pain (ie, valvular heart disease, pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal disease). MDCT findings were not correlated with coronary angiography and the overlying tissue described in MDCT could not be confirmed by autopsy. We didn’t evaluate in this study the presence or degree of systolic compression of the intramuscular coronary artery, and we could not produce the milking sign as seen on coronary angiography. The lack of ischemic correlates on stress testing limited the clinical relevance of the findings in the present study. Finally, the present study did not correlate MDCT findings with the effects of treatment, or follow-up results.

ConclusionsMDCT coronary angiography is an alternative noninvasive imaging tool that allows for easy and accurate evaluation of MB. The present study results suggest that MB is the likely cause of chest pain in a subgroup of younger patients with less prevalence of hyperlipidemia. Based on these data MB must be considered especially in young patients at low risk for coronary atherosclerosis but with angina-like chest pain or established myocardial ischemia. In these patients, MDCT may become the technique of choice for in vivo diagnosis of MB.

Conflict of interestNone declared

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our colleague radiologists (Ana Bustos, MD; Iñigo de la Pedraja, MD and Joaquín Ferreirós, MD, PhD), the nurses and technical radiology assistants for their expertise and commitment to working together for an excellent cardiac computed tomography service.

Received 9 December 2011

Accepted 2 February 2012

Corresponding author: Instituto Cardiovascular, Hospital Universitario San Carlos, Prof. Martín Lagos s/n, 28040 Madrid, Spain. albertutor@hotmail.com