Beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), angiotensin-II-receptor-blockers (ARB), and mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists decrease mortality and heart failure (HF) hospitalizations in HF patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. The effect is dose-dependent. Careful titration is recommended. However, suboptimal doses are common in clinical practice. This study aimed to compare the safety and efficacy of dose titration of the aforementioned drugs by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists.

MethodsETIFIC was a multicenter (n=20) noninferiority randomized controlled open label trial. A total of 320 hospitalized patients with new-onset HF, reduced ejection fraction and New York Heart Association II-III, without beta-blocker contraindications were randomized 1:1 in blocks of 4 patients each stratified by hospital: 164 to HF nurse titration vs 156 to HF cardiologist titration (144 vs 145 analyzed). The primary endpoint was the beta-blocker mean relative dose (% of target dose) achieved at 4 months. Secondary endpoints included ACE inhibitors, ARB, and mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists mean relative doses, associated variables, adverse events, and clinical outcomes at 6 months.

ResultsThe mean±standard deviation relative doses achieved by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists were as follows: beta-blockers 71.09%±31.49% vs 56.29%±31.32%, with a difference of 14.8% (95%CI, 7.5-22.1), P <.001; ACE inhibitors 72.61%±29.80% vs 56.13%±30.37%, P <.001; ARB 44.48%±33.47% vs 43.51%±33.69%, P=.93; and mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists 71%±32.12% vs 70.47%±29.78%, P=.86; mean±standard deviation visits were 6.41±2.82 vs 2.81±1.58, P <.001, while the number (%) of adverse events were 34 (23.6) vs 30 (20.7), P=.55; and at 6 months HF hospitalizations were 1 (0.69) vs 9 (5.51), P=.01.

ConclusionsETIFIC is the first multicenter randomized trial to demonstrate the noninferiority of HF specialist-nurse titration vs HF cardiologist titration. Moreover, HF nurses achieved higher beta-blocker/ACE inhibitors doses, with more outpatient visits and fewer HF hospitalizations.

Trial registry number: NCT02546856.

Keywords

It is estimated that the prevalence of heart failure (HF) is 1% to 2% in the general population and ≥ 10% in people older than 70 years, being a significant cause of hospital admissions.1,2 HF has a considerable social and health system impact.3

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend administration of beta-blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists (MRAs) to improve symptoms and prognosis, and reduce HF hospitalizations and mortality in HF patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) II-IV functional class and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%. These drugs must be titrated to reach the target dose, which implies the need for close clinical monitoring.1,2,4

Although the prescription of the above-mentioned drugs has improved, numerous observational studies reveal failure to comply with guidelines in terms of dosage. The reasons include patients’ clinical and sociodemographic characteristics, adverse events (AE), and medical professionals’ fear of AE occurrence, lack of awareness and shortage of time to perform the numerous visits and monitoring necessary for careful dose adjustment. Methods have been proposed to increase the number of patients with optimal doses, such as HF clinics, HF nurses, protocols and patient education,5–15 with drug titration by HF nurses being a widespread practice as recommended in guidelines.4,11,16–18

Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of HF programs demonstrate that multidisciplinary teams of specialized nurses and cardiologists who closely monitor patients while educating and optimizing treatment significantly reduce readmissions and mortality. Ten RCTs mention titration by HF nurses, usually with prespecified protocols and cardiologist support. Four of these RCTs evaluated the dose reached, although only 2 studies aimed to determine the dosage achieved by HF nurses.19–30

A systematic review on the safety and results of titration by HF nurses vs primary care physicians concluded that HF nurses were more effective.31 Nevertheless, no RCTs have evaluated the safety and effectiveness of titration by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists.

Therefore, the ETIFIC study (Enfermera Titula Fármacos en Insuficiencia Cardiaca) was a multicenter, controlled, randomized trial designed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of HF nurse up-titration of HF drugs compared with HF cardiologist titration, with a hypothesis of noninferiority.

METHODSStudy design and participantsThe design of the ETIFIC trial has been previously published.32 The trial was a 6-month, 2-arm, parallel, multicenter randomized controlled open-label trial carried out in 20 mostly tertiary, but with some secondary hospitals with HF units, in 10 Spanish autonomous communities.

Patients with HF, NYHA II-III and LVEF ≤ 40% were included after hospitalization in a cardiology ward. We excluded patients with elective surgery, contraindication to BB or already receiving 100% of the target dose or on the maximum tolerated dose, need for home or end-of-life care, or inability to care for themselves.

An active supervision system for the recruitment of eligible patients was established in each hospital, with centralized randomization in Galdakao Hospital, following a 1:1 intervention/control ratio, in blocks of 4 patients each and stratified by hospital, using computer generated tables. The randomization list generated by this process was concealed and safeguarded. A 4-month titration period was established, and a 6-month follow-up period after inclusion.

A safety and clinical adjudication committee, blinded to the group assignment, participant and hospital, monitored the safety of the research and evaluated all AE. In addition to the statement of the researchers from each site, AE monitoring included a review of all prespecified variables possibly associated with titration, and AE resolution at 4 months, as well as active supervision of admissions, mortality, and clinical reasons for loss of follow-up in all participants. All events were blindly evaluated by at least 4 members of this committee and, if there were discrepancies, by a fifth member. The final decision was made at least by 3 members. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Basque Country and the Ethics Committees of each hospital (n=20). Written informed consent was requested. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study protocolThe protocol of the 2 randomized groups, described in the previously published design article32 is briefly summarized:

HF nurse groupThe protocol was based on the European HF Guidelines.2,4 HF nurse requirements were 400hours HF training and at least 2 years of experience. HF nurses worked in a team with a HF cardiologist. The initial drug prescription and expected rate of titration was made by the cardiologist, while the titration process planning was made by the HF nurse. Weekly or fortnightly face-to-face visits were planned, and fortnightly drug up-titration, alternating different drugs, was considered. Clinical and analytical evaluation and patient education prior to each increase were required. Dose adjustment of just 1 drug at each visit, safety checklist review,32 and routine supervision by cardiologist were established. The titration process was tailored to each individual. The availability of a cardiologist for consultation or visits and early care for decompensation were also established.

HF cardiologist groupUsual care provided at HF units was planned. A HF cardiologist was responsible for prescription and titration, also based on European Society of Cardiology guidelines and addenda2,4 and a control nurse was responsible for clinical evaluation and self-care education, similar to the HF nurse group with the exception of the titration process. The number of visits depended on the organization of each hospital.

In the HF cardiologist group no nurse performed the implementation of the titration and all dose changes were made by the cardiologist. In the HF nurse group, in all cases, it was the nurse who carried out the titration, and therefore we can confirm that there was no crossover during the study.

Primary endpointThe primary objective was to compare the achieved beta-blocker mean relative dose (% relative to target dose) in the HF nurse and HF cardiologist groups after 4 months of titration. The % of target dose was defined following the target dose recommendations of the ESC HF guidelines.2

Secondary endpointsThe secondary objectives were to compare the following between the 2 groups: a) the mean relative doses of ACE inhibitors, ARB and MRA, after 4 months of titration; b) the percentage of AE attributable to dose changes over the 4 months of titration; c) variables influencing target dose achievement; d) rates of mortality and readmissions at 6 months after the start of titration; and e) changes in LVEF, NYHA class, 6-minute walk distance, NT-proBNP levels and quality of life scores throughout the study according to group allocation.

A noninferiority hypothesis was set. Variables are shown in the design article.32

Sample size calculationFor the hypothesis that the relative dose of BBs would reach 52% by the end of the study and using an equivalence margin of 7%, we would need 157 patients per group for an alpha level of significance of .05 and a statistical power of 80% (beta of 0.80). Hence, estimating that as many as 20% of patients would be lost to follow-up, we needed to recruit 314 patients per group to test the main hypotheses.32

Statistical analysisThe analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Both the Student t test (or the nonparametric Wilcoxon test if continuous data were not normally distributed) and the chi-square test (or Fisher exact test) were used to compare the baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the 2 groups. The effect attributable to the intervention was estimated by comparing the differences in the relative dose of BB (primary endpoint of the study), ACE inhibitors, ARB and MRA reached between the groups, assessed at 4 months after the start of titration, and the 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was calculated. We performed multivariate analysis for the primary and secondary endpoints as predefined in the original study design.32 The model was adjusted by baseline dose, age, educational level, baseline heart rate, amiodarone and the number of visits of the professional who titrated the target dose/additional visit; these were established as relevant related factors with a possible effect on dosing, based on a review of the literature. All variables with P <.20 were included as explanatory variables in a multivariate model, with relative dose as the response variable. The effect of time was estimated in 2 repeated measurements for each participant, using mixed linear regression models with fixed effects (time, intervention, interaction between time and intervention) and random effects (specific effect of each participant and center at the reference level and the effect of time). These models took into account the longitudinal structure of the 2 repeated measurements, as well as the hierarchical and multicenter structure of the data. All statistical analyses were performed, using SAS System v 9.4, with statistical significance set at P <.05.

Survival analysis was estimated using Kaplan-Meier tables and the survival rate of each group was compared using the log-rank test.

See the .

RESULTSPatient populationA total of 824 patients with de novo HF were evaluated in 20 hospitals (2015- 2018). We excluded 504 patients, the main causes being elective surgery and already taking the maximal BB dose (figure 1). We included 320 patients, of whom 164 were randomized to the HF nurse group and 156 to the HF cardiologist group. Finally, 289 patients were analyzed at 4 months, 144 vs 145, and 274 at 6 months, 136 vs 138, respectively, due to losses to follow-up.

Patient characteristics were generally well-balanced between the 2 groups, although the HF nurse group had lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and a higher score (worse) in the Minnesota living with HF Questionnaire (table 1 and shows loss to follow-up causes and shows other baseline characteristics).

Baseline patient characteristics

| Variables (at hospital discharge) | HF nursen=164 | HF cardiologistn=156 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 61.88±12.14 | 60.64±12.25 | .37 |

| Female sex | 45 (27.44) | 38 (24.36) | .53 |

| Educational level, ≤ 10 y | 53 (35.52) | 55 (35.26) | .61 |

| Patients aged ≥ 70 y | 44 (26.83) | 39 (25.00) | .71 |

| Memory impairment screening ≤ 4 | 7 (17.95) | 5 (13.89) | .63 |

| Lawton test: inability to administer medication | 17 (43.59) | 16 (44.44) | .94 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 90 (54.88) | 76 (48.72) | .27 |

| Smoker | 51 (31.1) | 46 (29.49) | .75 |

| Alcohol consumption> 2 units/d | 44 (26.83) | 50 (32.05) | .31 |

| Diabetes | 50 (30.49) | 45 (28.85) | .75 |

| Heart disease | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | 45 (27.44) | 43 (27.56) | .98 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 52 (34.67) | 40 (26.85) | .14 |

| NYHA | |||

| II | 139 (84.76) | 128 (82.05) | .52 |

| III | 25 (15.24) | 28 (17.95) | .52 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 27.95±6.69 | 27.45±7.25 | .53 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 12 (7.32) | 10 (6.41) | .75 |

| Stroke | 6 (3.66) | 10 (6.41) | .26 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 18 (10.98) | 23 (14.74) | .31 |

| Charlson index, adjusted by age | 4.74±1.91 | 4.86±1.97 | .58 |

| Vital signs | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 115.59±17.72 | 115.38±19.45 | .92 |

| SBP ≤ 100 mmHg | 30 (18.29) | 38 (24.52) | .18 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 72.25±13.44 | 73.03±14.58 | .59 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL, n; median [IQR] | 145; 1589 [2698] | 139; 1765 [2791] | .81 |

| BNP, pg/mL, n; median [IQR] | 19; 307 [630] | 14; 397 [709] | .62 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.13±0.49 | 1.04±0.51 | .12 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 71.56±21.55 | 77.97±22.06 | .009 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 44 (26.82) | 28 (17.94) | .06 |

| Potassium> 5 mEq/L | 16 (9.76) | 20 (12.82) | .39 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.15±1.85 | 14.04±2.22 | .64 |

| Anemia | 39 (23.78) | 43 (27.56) | .44 |

| 6-minute walk test, meters | 361.83±102.19 | 370.52±108.26 | .47 |

| European HF self-care behaviour scale (12-60) | 36.62±12.15 | 35.85±11.37 | .56 |

| Question 10 irregular medication intake (score 3-5) | 23 (14.11) | 21 (13.63) | .90 |

| Quality of life | |||

| Minnesota Living with HF Questionnaire (0-105) | 50.8±22.61 | 45.71±22.21 | .04 |

| EQ-5 D index | 0.73±0.23 | 0.75±0.24 | .54 |

| VAS EQ-5D (0-100) | 58.27±20.34 | 56.98±19.04 | .56 |

| Drugs | |||

| Beta-blockers | 159 (96.95) | 151 (96.9) | .94 |

| ACE inhibitors | 136 (82.93) | 130 (83.33) | .92 |

| ARB | 20 (12.2) | 12 (7.69) | .18 |

| MRA | 127 (77.44) | 122 (78.21) | .87 |

ACE, inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; HF, heart failure; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor blocker; NT-proBNP, N-terminal proBNP; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SBP, systolic blood pressure; VAS, visual analog scale.

The data are expressed as N (%), mean±standard deviation, or N; median [IQR].

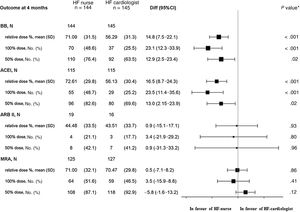

The noninferiority hypothesis was confirmed in BB mean relative doses (% of target dose recommended in ESC guidelines) achieved by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists at the end of the titration period, 4 months after discharge (figure 2).

Dosage achieved at 4 months (after the titration period). 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta-blockers; Diff, difference; HF, heart failure; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor blocker; n total number of patients, No. (%), number of patients with medication prescribed during the tritration period, withdrawals included; SD, standard deviation. * P value of the interaction between treatment and each subgroup.

The relative BB dose achieved in the HF nurse group was significantly higher than the HF cardiologist group, P <.001, as well as the % of patients in BB target dose and % of patients with dose ≥ 50% of the target dose.

The BB dose was increased during the titration period in more patients in the HF nurse group with statistically significant differences vs HF cardiologist group, 113 (78.47%) vs 88 (60.69%), P=.001 ().

Secondary endpointsACE inhibitors/ARB/MRA dosageThe noninferiority hypothesis (HF nurses vs HF cardiologists) was also confirmed in the analysis of the relative doses of ACE inhibitors, ARB and MRA achieved after the titration process, according to allocation (figure 2).

The relative ACE inhibitor dose was significantly higher in the HF nurse group than in the HF cardiologist group, as well as the % of patients in the target dose and dose ≥ 50% of the target dose.

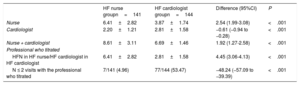

Variables potentially associated with higher drug doses at the end of the titration periodAfter comparison of variables potentially associated with higher drug doses (blood pressure, heart rate, renal function, potassium, flexible diuretic regimen, European Heart Failure Self-care Behavior Scale, number of visits (table 2), baseline doses and prescription of titrated drugs, other hypotensive or rate-lowering drugs and other variables shown in ) in the HF nurse vs HF cardiologist groups, significant differences were only found in the number of visits: 6.41 (2.82) vs 2.81 (1.58), P <.001 and the application of the flexible diuretic regimen: 82 (69.49%) vs 66 (55.00%), P=.02.

Visits

| HF nurse groupn=141 | HF cardiologist groupn=144 | Difference (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse | 6.41±2.82 | 3.87±1.74 | 2.54 (1.99-3.08) | <.001 |

| Cardiologist | 2.20±1.21 | 2.81±1.58 | −0.61 (−0.94 to −0.28) | <.001 |

| Nurse + cardiologist | 8.61±3.11 | 6.69±1.46 | 1.92 (1.27-2.58) | <.001 |

| Professional who titrated | ||||

| HFN in HF nurse/HF cardiologist in HF cardiologist | 6.41±2.82 | 2.81±1.58 | 4.45 (3.06-4.13) | <.001 |

| N ≤ 2 visits with the professional who titrated | 7/141 (4.96) | 77/144 (53.47) | −48.24 (−57.09 to −39.39) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HFN, heart failure nurse.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Although it is not possible to discriminate those visits that resulted in dosage modification, HF nurse consultation with HF cardiologists in the event of AE or for the management of other drugs was standardized. The number of registered HF nurse consultations with the HF cardiologist, without patient visits, were mean±standard deviation, 1.55±1.77 ().

Dosage heterogeneity was found between hospitals in both groups ().

Multivariate analysisThe multivariate analysis is described in detail in and .

The relative BB, ACE inhibitor and ARM doses achieved increased during the 4 months of follow-up (P <.001, P=.003, and P=.46, respectively).

At 4 months, the adjusted difference in average dose between the 2 groups, observed in a multivariate model, was 12.18% (95%CI, 6.19-18.17) (P <.001), in favor of the ETIFIC HF nurse group for BBs and 13.79% (95%CI, 8.58-18.99) (P <.001) for ACE inhibitors.

Factors related to the BB dose achieved were baseline dose, age, educational level, baseline heart rate, amiodarone and the number of visits of the professional who titrated (1.44% of the target dose/additional visit; P<.002). Only baseline dose level, baseline systolic blood pressure and eGFR <60 were related to the ACE inhibitor dose achieved.

The reasons, systematically registered by the researchers, for not reaching the target dose are described in the .

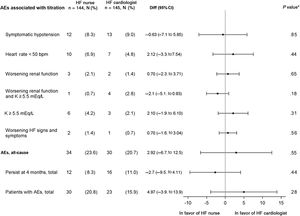

Adverse eventsThe noninferiority hypothesis (HF nurse vs HF cardiologist) regarding AE potentially associated with drug titration was met. The most frequent AE were symptomatic hypotension, bradycardia, worsening renal function, and/or hyperkalemia.

As shown in figure 3, there were no significant differences in terms of overall or individual AE occurrence between the 2 allocation groups. Most AE were corrected at 4 months.

Adverse events associated with titration. The events persisting at 4 months were also evaluated. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AE, adverse event; bpm, beats per minute; Diff, difference; HF, heart failure; K, potassium; worsening renal function, creatinine> 50% baseline, creatinine> 3mg/dL, estimated glomerular filtration rate <25mL/min/1.73 m2; n total number of patients, No.(%), number of cases. * P value for difference between treatment groups.

AE were frequent with concomitant prescription of other rate-lowering drugs (especially amiodarone), hypotensive drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and metformin ( shows events associated with titration; shows causes, shows baseline measurement events, shows associated factors and shows withdrawal causes).

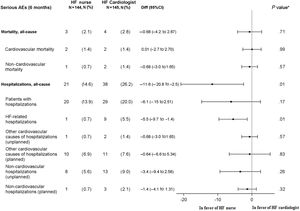

Serious adverse events at 6 monthsThe noninferiority hypothesis regarding mortality and admissions was confirmed. There were 2 cardiovascular deaths (1.4) in HF nurse group: 1 multiple organ failure due to evolved myocardial infarction, 1 sudden cardiorespiratory arrest. There were 2 deaths in HF cardiologist group: 1 cardiorespiratory arrest and 1 cardiorenal failure. See Kaplan-Meier curves for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in .

There were statistically significant fewer HF admissions in the HF nurse group: 1 (0.7%) vs HF cardiologist 9 (5.5%), P=.01. Other non-elective cardiovascular hospitalizations were 1 symptomatic bradycardia (0.7%) in the HF nurse group vs 2 strokes (1.4%) in the HF cardiologist group, P=.57. (figure 4). Other admission causes are shown in .

Clinical outcomes at 6 monthsThe noninferiority hypothesis was reached in terms of LVEF, NT-proBNP, 6-minute walk test, NYHA, and quality of life. There were significant improvements in all these outcomes but without significant differences between the 2 groups (table 3).

Outcomes at 6 months

| Variables | HF nursen=136 | HF cardiologistn=138 | Difference of change from baseline to 6 months between groups (95%CI) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | Baseline | 6 months | |||

| LVEF % | 27.75±6.77 | 43.39±13.45 | 27.29±7.18 | 42.75±10.61 | 0.07 (−2.69 to 2.83) | .96 |

| LVEF <35% | 108 (80.6) | 36 (26.87) | 108 (80) | 23 (17.04) | 9.70 (−2.04 to 21.44) | .11 |

| LVEF> 40% | 0 (0) | 64 (47.76) | 0 (0) | 75 (54.74) | 6.98 (−4.89 to 18.86) | .25 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL, n; median [IQR] | 117; 1357 [2020] | 117; 535 [1222] | 121; 1525 [2811] | 121; 534 [848] | 16.47 (748 to −781) | .97 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 11; 264 [528] | 11; 267 [601] | 11; 372 [673] | 11; 109 [138] | −117.18 (−568 to 334) | .59 |

| NYHA class | ||||||

| I | 0 | 59 (43.7) | 0 | 47 (34.31) | 9.40 (−2.14 to 20.94) | .11 |

| II | 113 (83.7) | 72 (53.33) | 114 (83.21) | 86 (62.77) | 9.93 (−0.35 to 20.22) | .60 |

| III | 22 (16.3) | 4 (2.96) | 23 (16.79) | 4 (2.92) | −0.54 (−8.68 to 7.61) | .90 |

| 6-minute walk test, meters | 356.03±9.51 | 413.78±111.78 | 373.51±103.02 | 424.00±106.02 | 7.28 (−11.27 to 25.83) | .44 |

| Minnesota*score | 50.33±22.37 | 23.96±19.12 | 45.91±22.61 | 20.90±20.70 | −0.91 (−6.63 to 4.81) | .75 |

| Euroqol-5 dimension index | 0.74±0.22 | 0.81±0.20 | 0.75±0.24 | 0.80±0.24 | 0.04 (−0.2 to 0.01) | .20 |

| Visual analog scale | 57.96±20.59 | 70.47±19.60 | 56.86±18.67 | 70.20±19.38 | −0.61 (−5.99 to 4.78) | .82 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal proBNP; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data are expressed as N (%), mean±standard deviation, or N; median [IQR].

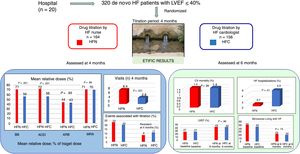

ETIFIC is the first multicenter, controlled and randomized clinical trial comparing the safety and effectiveness of titration of BB, ACE inhibitors/ARB and MRA by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists (gold standard), demonstrating the hypothesis of noninferiority in dosage, AE, and clinical outcomes. Moreover, HF nurses achieved higher BB/ACE inhibitors doses, and fewer total and HF hospitalizations, at the expense of a higher number of outpatient visits.

Primary endpointThe HF nurse group achieved a BB relative dose and target dose that were not inferior to the HF cardiologist group, with statistically significant differences favouring HF nurses. The number of visits, which was higher in the HF nurse group than the HF cardiologist group, was associated with a higher dosage. However, after adjusting the multivariate analysis by this variable, among others, we found that HF nurses still achieved better results (figure 5).

Take home figure. ETIFIC is the first multicenter randomized trial to demonstrate the noninferiority of drug titration by HF nurses vs drug titration by HF cardiologists. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta-blockers; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; HFC, heart failure cardiologist; HFN, heart failure nurse; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor blocker.

The relative doses of both ETIFIC groups were lower than the weighted average achieved in RCT of BB (HF nurse −6%, HF cardiologist −21%), as well as in those measuring the target dose (HF nurse −10%; HF cardiologist −33%). These differences could be explained by the characteristics of the ETIFIC patients, all recruited after HF admission, the lower mean systolic blood pressure and heart rate, and the greater presence of diabetes, respiratory disease and smoking compared with patients in RCT.

The target doses achieved in 2 RCTs of HF nurse titration programs were close to the ETIFIC HF nurse group and higher than those in the HF cardiologist group, although these trials had small sample sizes.22,29 A RCT with joint cardiologist-nurse titration achieved lower relative doses than both ETIFIC groups. An exercise program achieved a relative dose close to the HF nurse group (see [BB RCT, 1-22]).

Previous observational studies showed wide heterogeneity in their results (relative dose 33%-63% and target dose 12%-58%).6–9,11–13,18 Those who reported having a HF nurse showed better results.

The relative ETIFIC HF nurse dose was 8% higher than an observational study dose with HF-clinic/HF-nurse18 and 23% higher than those who did not report having a HF nurse.7,9 The target dose was 15% higher than the average weighted observational studies with a HF nurse11,18 and 30% higher than the average of those who did not have a HF nurse.6,7,12,13

The HF clinics and HF nurses, as in ETIFIC, guarantee access to specialized health professionals and a sufficient number of consultations for titration, a key aspect of our study.

In contrast, the relative ETIFIC HF cardiologist dose was 7% lower than that in an observational study with HF nurses18 and 8% higher than that in those without HF nurses.7,9 The target dose was also 8% lower than that in observational studies with HF nurses8,11,18 and was 7% higher than those without HF nurses. 6,7,12,13

In addition, the percentage of patients within the target dose of the HF cardiologist group was almost double than the observed in the Spanish long-term HF Registry6 cohort (same country, similar health professionals). This suggests that a controlled environment such as a randomized trial, with a specific titration project, a protocol and assignment of a responsible professional, can improve results, as previously stated.8,11,13,14

The ETIFIC patient comorbidity profile was close to those in previous observational studies, reinforcing its applicability, although the mean age was 8 years lower because patient inclusion was strictly limited to those with de novo HF.6–9,11–13,18

However, the prescription of the 3 drug groups (BB, ACE inhibitors/ARB/ARB-neprilysin inhibitor, MRA) was much higher in ETIFIC (81%/79%) than in RCT and observational studies,6–9,11–13,18 mainly due to the low prescription of MRA in previous studies (RCTs: 11%-41%; observational studies: 15%-74%). This further enhances the feasibility of dosage improvement in a context of optimal prescription, as shown in ETIFIC (see [BB observational studies 23-34]).

Secondary endpointsNoninferiority was also confirmed in the ACE inhibitor dose achieved by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists with statistically significant differences favoring HF nurses.

As with BB, the 2 groups achieved doses lower than RCTs of ACE inhibitors and ARB. The difference could be explained by the lower baseline systolic blood pressure, the low prescription of MRA and BB (these studies were performed many years ago) and withdrawals in RCTs (up to 32%).

The ACE inhibitor/ARB doses in previous observational studies also showed greater heterogeneity.6–8,11–13 Systolic blood pressure was higher than in ETIFIC. As in ETIFIC, studies that reported having HF nurses8,11 achieved target doses twice as high as those without HF nurses,12,13 except one.

Regarding MRA, the 2 ETIFIC groups achieved doses 13% lower than those in the RCTs. It is difficult to compare observational studies, given the low prescription of MRA compared with ETIFIC (see [RCT: ACE inhibitors 14,15,35,36 and ARB 37-39, MRA 40,42; observational studies 23, 26-31]).

The number of HF nurse visits in ETIFIC was not higher than in other HF-clinic/HF nurse studies, and therefore could be considered adequate to ensure a careful titration process.

This study also demonstrated noninferiority in terms of mortality and hospital admissions. In addition, there were fewer total and HF-related hospitalizations in the HF nurse group, probably related to a higher BB and ACE inhibitor dosage, number of visits, and application of the flexible diuretic regimen.

Six-month HF hospitalization and mortality in both ETIFIC groups were lower than those reported in the literature, probably due to therapeutic optimization and inclusion of de novo HF patients only.

Noninferiority was also confirmed in the 6-month clinical outcomes, demonstrating major improvement in LVEF, NT-proBNP, NYHA, 6-minute walk, test and quality of life without significant differences between both groups.

The improvement in mean LVEF after optimization in both ETIFIC groups (15%) exceeded that achieved in the RCT of BB (6%), ACE inhibitors (2.1%), ARB (4.3%) and MRA (3.4%), considered individually. However, it was closer to observational studies in which the optimization of drugs was evaluated grouped as follows: 22% to 70% of patients showed an improvement in LVEF ≥ 10% and 51% of patients exceeded LVEF 35%. This reinforces the previously described practices2 of reevaluating LVEF after optimization, prior to contemplating therapies such as cardiac defibrillators or cardiac resynchronization.

The increase in meters covered in the 6-minute walk test in both ETIFIC groups,> 50 meters after the titration process, could be associated, according to the BIOSTAT study, with a significant reduction in HF hospitalization and mortality.

The significant deterioration in baseline quality of life, similar to that seen in previous studies after hospital admission, and marked improvement at 6 months, similar to that in studies after optimization in HF clinics, showed the benefit of this process.

The specific study of dosage based on age or sex and the in-depth study of factors associated with improvement of LVEF, quality of life, and the 6-minute walk test go beyond the scope of this study and could be the subject of future research (see [visits 43; serious AE 43-46; LVEF 1,2,4-6,8-11,16,18, 36,37,47-84; the 6-minute test 85; quality of life 26,86]).

Study strengths and limitationsThe external validity was represented by 20 hospitals and 10 different health systems. The participants were closer to the real-world population than the highly selected participants in randomized drug trials in terms of their comorbidities. However, the external validity of the study is limited by the implementation of ETIFIC in a single country. Other limitations of the ETIFIC trial are its recruitment characteristics, inclusion of de novo HF patients exclusively, relatively young patients and the low percentage of women and patients with ischemic heart disease. Substudies of older patients in the ETIFIC trial and sex differences remain the focus for further research. Moreover, further similar studies on the implementation of this protocol for home care patients, such as the intervention of HF nurses at home with the support of cardiologists, or nonface-to-face interventions, or for patients admitted to other hospital areas, or ambulatory patients, could be designed to assess this vulnerable population.

Clinical implicationsOrganizing care with a HF nurse responsible for titration can help to improve guideline implementation. ETIFIC requirements for HF nurses, protocol and measurements could also help to enhance quality indicators of the titration process.

CONCLUSIONSETIFIC is the first multicenter randomized trial that demonstrates noninferiority in the safety and effectiveness of drug titration by HF nurses vs HF cardiologists in de novo HF patients with reduced LVEF admitted to cardiology wards. The HF nurse group achieved higher BB and ACE inhibitor doses and fewer total and HF hospitalizations, with a larger number of outpatient visits. HF nurses should have adequate training, experience and time, a HF cardiologist prescription, expected rate of titration, the possibility of consulting with a HF cardiologist, a safety checklist, and screening of the process.

FUNDINGThis work was supported by grants from Carlos III Health Research Institute (FIS PI14/01208) in coordination with the European Regional Development Fund, and the Government of the Basque Country (Exp. 2014111143). Neither funding source was an industry sponsor, and both are public institutions. ETIFIC researchers were independent the from funders in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, drafting of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- -

Mortality and HF hospitalizations decrease with administration of BB, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists to HF patients with reduced LVEF.

- -

These drugs must be titrated to reach the target dose, which implies close clinical monitoring. The effect is dose-dependent.

- -

Suboptimal doses are common in clinical practice.

- -

ETIFIC is the first multicenter randomized trial to demonstrate the noninferiority of HF nurse titration vs HF cardiologist titration.

- -

HF nurses achieved higher BB/ACE inhibitor doses, and fewer HF hospitalizations, without increasing AE, but at the expense of a higher number of outpatient visits.

- -

Organizing care with a HF nurse responsible for titration can help to improve the implementation of clinical practice guidelines.

- -

HF nurses should have adequate training, experience and time, a HF cardiologist prescription, an expected rate of titration, the possibility of consulting with a HF cardiologist, a safety checklist, and screening of the process.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2020.04.016