Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Persistent patent foramen ovale (PFO) is common in adults and a 25% prevalence in the general population has been reported.1 The presence of PFO is usually discovered by chance and has no clinical repercussions. However, the possible association of PFO with clinical signs and symptoms of embolic stroke,2 platypneaorthodeoxia syndrome,3 decompression sickness in divers,4 or migraine5 has been reported. Optimal treatment of PFO remains undefined and many studies publish contradictory results.

Because of the controversy regarding the clinical significance of PFOs, the high prevalence of these lesions, and the variety therapeutic options available, increased attention has been directed towards this condition in the last years.

In the present article, we offer a practical, concise review of this entity, including epidemiologic, anatomic, clinical and therapeutic aspects.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

A review of the available, autopsy-derived data reveals an estimated ±25% prevalence of PFO in the adult population.1,6,7 Prevalence falls with age and is 20% in patients over 80 years.1 No significant differences have been found in prevalence between men and women.1

Patent foramen ovale size ranges from 1 to 19 mm (mean, 4.9 mm) and increases with age. In the first decade of life, mean diameter is 3.4 mm, reaching 5.8 mm in patients aged >90.1

EMBRYOLOGY

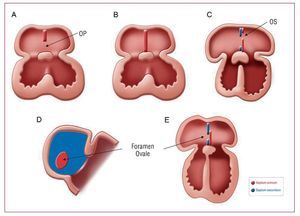

Foramen ovale is an interatrial communication that is needed during the life of the fetus as it facilitates the passage of oxygenated blood from the placenta to the fetal circulatory system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Embryologic formation of foramen ovale. A: septum primum begins to grow from the mid-portion of the common atrium roof towards the endocardial cushions and the ostium primum (OP) remains between them. B: septum primum fusion with endocardial cushions. C: a second wall begins to form, septum secundum, to the right of the septum primum; a second orifice, ostium secundum (OS), forms in the upper portion of the septum primum; the septum secundum finally covers the OS. D: lateral view of the interatrial wall with foramen ovale. E: frontal view of the interatrial wall.

Immediately after birth, pressure in the right side of the heart and pulmonary vascular resistance diminish abruptly as the pulmonary alveoli fill. This, together with greater pressure in the left atrium due to increased venous return, produces functional closure of the foramen ovale. During the first 2 years of life, the 2 sides fuse together and, consequently, the fossa ovalis is covered by the membrane tissue of the septum primum only.

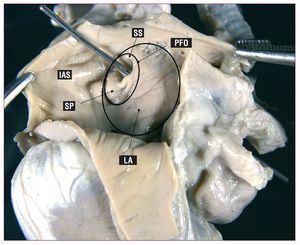

When this closure does not occur, the foramen ovale remains permeable into adulthood (Figure 2). This can produce right-to-left shunting during the crossover of pressure that occurs in the respiratory cycle, fundamentally at end-diastole or in situations when right atrial pressure increases (coughing, Valsalva maneuver).

Figure 2. Photograph showing PFO by way of the passage of a metal probe; it also shows adjacent structures. LA indicates free wall of the left atrium; PFO, patent foramen ovale; IAS, interatrial septum; SP, septum primum; SS, septum secundum.

ANATOMIC ASSOCIATIONS

Patent foramen ovale is associated with other cardiac disorders.

Atrial Septal Aneurysm (ASA)

Interatrial septal aneurysm is considered to occur when part or all the interatrial septum presents dilatation protruding into the right or left atrium during the respiratory cycle. Although different definitions exist, it is generally considered that minimum ASA mid-lateral displacement is >15 mm.8 Prevalence in the general population is 1% in autopsy studies,9 0.22%-1.9% in transthoracic echocardiography,10 2.2%-4% in transesophageal echocardiography,11,12 and 4.9% in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.13 It is reported that 33% of patients with ASA also present PFO.14 Moreover, PFO size is usually greater in patients with ASA.15

Chiari Networks

A Chiari network is an embryologic remnant of the right venous sinus valve, present in 2%-3% of the population.16 In echocardiography, it appears as a linear, hypermobile, refractile image following the line of the atrial roof or interatrial septum. In adults, a Chiari network maintains flow from the vena cava to the interatrial septum. Therefore, Schneider et al17 suggest it could favor PFO and ASA; 83% of patients with a Chiari network also present PFO and 24% present ASA.17 Moreover, frequency is greater in patients with cryptogenic stroke than in those undergoing echocardiography for other causes (4.6% vs 0.5%), indicating it could facilitate paradoxical embolism.17

Other Associations

Patent foramen ovale can appear in association with interatrial septal defects (ASD). Khositseth et al18 found 10% of patients referred for PFO closure also presented IWD.

In some series, £80% of patients with Ebstein anomaly present PFO. This association may be due to right atrial distension caused by tricuspid insufficiency.19

Other situations in which right atrial pressure increases, such as mitral stenosis, mitral insufficiency, persistent ductus arteriosus, pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular insufficiency, or pulmonary embolism, may facilitate foramen ovale dilatation and cause right-to-left shunting.

DETECTION

We recommend ruling out the possibility of PFO in patients with stroke of unknown origin.

Echocardiographic techniques such as transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), or transcranial echocardiography (TCE) have been used to detect PFO. Although second harmonic imaging has increased TTE sensitivity,20,21 TEE remains the standard technique. The most recent studies comparing echocardiographic techniques are summarized in Table 1.21-27

Transthoracic Echocardiography

As color Doppler detects only 5%-10% of interatrial shunts,28 patients referred to the echocardiography laboratory with suspected PFO should undergo a contrast study. Although different types of contrast material exist, the most widely-used technique continues to be the injection of agitated saline solution microbubbles. This should be performed both at rest and with maneuvers that increase right atrial pressure (Valsalva, coughing), as this improves diagnostic sensitivity.21,29 The apical 4-chamber plane is usually the most appropriate for this type of study. The presence of a single microbubble in the atrium and left ventricle in the first three beats after right cavity opacification is considered diagnostic of PFO.30 In most patients, the appearance of microbubbles following the third beat corresponds to intrapulmonary shunting.

The number of microbubbles crossing the PFO enables us to quantify shunting. However, authors disagree about how to classify degrees of severity as methods vary significantly because of differences in the number of microbubbles injected, injection velocity, the route chosen, or the quality of the Valsalva maneuver.31 Instead of counting microbubbles, some echocardiography laboratories classify severity as complete left chamber opacification, almost complete opacification or slight opacification. Notwithstanding, it is considered that the greater the number of bubbles or degree of opacification, the greater the probability of paradoxical embolism.32

As well as PFO detection, TTE facilitates ruling out ASA and, when PFO is detected by color Doppler, helps determine the direction of shunting and determine the presence of one or more fenestrations.

The principal limitation of TTE is its relatively poor sensitivity by comparison with TEE (Table 1).21-27

Moreover, TTE definition in detailed studies of interatrial septal anatomy is inferior to that of TEE or intracardiac echography, arguing against its use as a complementary technique during percutaneous PFO closure.

Transesophageal Echocardiography

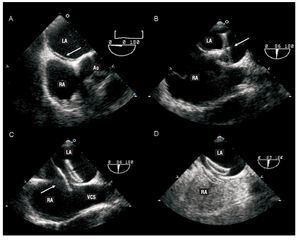

Contrast TEE and color Doppler should be considered if the transthoracic study is negative or dubious but strong clinical suspicion of PFO remains. Transesophageal echocardiography permits detailed study of the interatrial septum as it visualizes the lack of septum primum coaptation over the fossa ovale (Figure 3). Schuchlenz et al32 showed that PFO size, measured by balloon inflation during the closure procedure, correlates well with the septum primum-septum secundum distance measured by TEE.

Figura 3. Transesophageal echocardiography during percutaneous patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure procedure using an Amplatzer device (AGA Medical Corporation, Plymouth, Minnesota, USA). A: the existence of PFO (arrow) is demonstrated. B: passage of the guide through the PFO with deployment of the disc (arrow), which will be implanted in the left atrium. C: deployment of the second disc (arrow) in the right atrium. D: contrast study showing absence of residual shunting. RA indicates right atrium; LA, left atrium; Ao, aortic valve; SVC, superior vena cava.

The main limitation of TEE is the general use of sedation or anesthesia while it is performed, making Valsalva maneuvers difficult. Sometimes, pressure on the abdomen can increase the pressure in the right chambers but its diagnostic sensitivity is less than with other maneuvers.

Before interventions, TEE facilitates ruling out other possible causes of cardiac emboli, locating and checking the number of defects, and determining whether other concomitant lesions exist. During the intervention, TEE provides direct monitoring guidance in deploying the device to ensure it is correctly positioned and avoid complications or interference with other structures. It also facilitates measuring tunnel size and characterizing tunnel shape. These data are important because in very long or very tortuous tunnels some authors argue against crossing the PFO and suggest using transeptal puncture as an alternative means of achieving adequate device deployment.33 Finally, during the intervention, TEE is extremely useful to determine the size of the device to be implanted (Figure 3).

Other TechniquesTranscranial Doppler (TCD) echocardiography.

This technique has high sensitivity in detecting PFO22; it registers microbubbles passing into cerebral circulation after they are injected into the venous system. It is recommended that the mid-cerebral artery be used, that the injection be given at rest and accompanied by the Valsalva maneuver if necessary. A classification system based on the number of bubbles detected in the first 40 s after injection is recommended: 0 microbubbles (negative result), 1-10 microbubbles, >10 microbubbles without opacification and complete opacification.34 The principal limitations of TCD are that it only indicates the existence of right-to-left shunting, does not distinguish between intracardiac and other extracardiac shunting, and provides no anatomic information about PFO at all.34

Cardiac magnetic resonance (MR). Few comparative studies of MR and TEE have been made. Nusser et al35 compared 211 studies with MR and TEE and concluded that MR is inferior to TEE in the detection of right-to-left shunting and in identifying ASA.

Three-dimensional echocardiography (3D Echo).

This technique has demonstrated its usefulness in determining interatrial defect size and shape. However, in PFO its value is minimal because defects are smaller and dynamic, and 3D Echo resolution does not register them.36

Intracardiac echography (ICE). The usefulness and safety of ICE in percutaneous PFO closure has been described elsewhere.37 This technique differs from TTE in that general anesthesia is not required; ICE enables us to adequately characterize PFO, tunnel, septum and shunting; it is extremely useful in percutaneous closure device deployment. Limitations include the cost of the probe, the use of £9 Fr venous access, and the need for an experienced operator.37

CLINICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

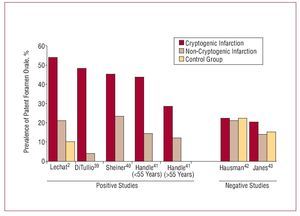

Cryptogenic Stroke

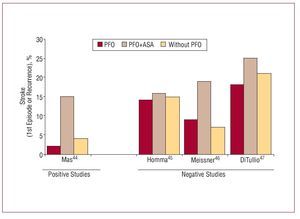

Approximately 40% of ischemic strokes are cryptogenic, that is, of no apparent cause.38 The association between PFO and cryptogenic stroke remains controversial since reported results are contradictory (Figures 4 and 5).2,39-47 Studies referring this association suggest different mechanisms are involved: a) paradoxical embolism, with the passage of thrombus from the peripheral venous system to left cardiac cavities through the PFO; b) formation of thrombus in the atrium as a consequence of PFO-related arrhythmias; c) formation of thrombus in the foramen ovale canal; and d) PFO-related hypercoagulability. In the PICCS study (PFO and Cryptogenic Stroke Study), Homma et al45 found a greater size of the defect and greater degree of shunting presented a grater risk of cryptogenic infarction. Other risk factors may include spontaneous shunting at rest, without Valsalva maneuvers,48,49 >5 mm separation between septum primum and septum secundum,24,50 or presence of ASA.41

Figure 4. Summary of the principle observational studies analyzing the relation between cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale. It shows the prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic infarction, non-cryptogenic infarction and control group.

Figure 5. Summary of the principle prospective studies analyzing the relation between cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale (PFO). It shows the percentage of patients presenting a first episode of stroke or recurrent infarction in the follow-up according to whether they had PFO or PFO+ISA or did not have PFO.

In the meta-analysis conducted by Overell et al,51 patients aged <55 with PFO presented a greater risk of ischemic events and recurrence than patients >55 years (odds ratio [OR]=6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.7-9.6 vs OR=2.26; 95% CI, 0.9-5.3). Moreover, the subgroup of younger patients with ASA and PFO presented a high risk of ischemic events (OR=15.5; 95% CI, 2.8-85.8) by comparison with those presenting only PFO or only ASA. However, a recently published study shows a relation between PFO and cryptogenic infarction in both younger (<55 years) and older (>55 years) populations.41 Moreover, it again confirms that in both groups this association was greater than in patients presenting ASA.41

Migraine

In recent years, migraine has been indicated to be a factor independent of ischemic stroke, fundamentally in women aged <45, presenting migraine with aura.52,53

In fact, prevalence of subclinical lesions in the cerebellum in these patients is 15-fold greater than in control groups.54 Some hypotheses indicate this type of migraine is caused by the passage of small venous emboli through the PFO. Anzola et al5 found 48% prevalence of PFO in patients with migraine with aura, 23% prevalence in patients with headache without aura and 20% prevalence in control group patients. Wilmshurst et al55 found migraine with aura was more frequent in patients with larger PFO with spontaneous shunting at rest. All these findings have led to PFO closure being proposed as the treatment for this type of migraine in selected patients.

Platypnea-Orthodeoxia Syndrome

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome (POS) is characterized by dyspnea and hypoxemia on assuming an upright posture that improve in decubitus and supine positions. The syndrome can be caused by right-to-left cardiac or pulmonary shunting, though in each case the mechanisms differ. In intracardiac shunting through a PFO, postural hypoxemia seems a consequence of redirecting flow in the inferior vena cava towards the interatrial septum due to the distortion of anatomic relations. Diagnosis of PFO with POS should be by tilt-test, measuring arterial saturation in different positions, and contrast echocardiography, which should show intracardiac shunting.56

Other

Decompression syndrome. The association between PFO and decompression syndrome in divers has been shown.4 It is more frequent in those with shunting at rest, ASA and larger PFO.4

Systemic embolism. Cases of acute myocardial infarction57,58 and renal infarction59 associated with PFO have been reported.

TREATMENT

Migraine

The available data are insufficient for us to recommend percutaneous or surgical PFO closure in these patients.

Several nonrandomized studies have described improved symptoms in patients with migraine after PFO closure.60

In our study, we found £76% of patients with migraine experience a significant reduction in frequency or intensity of episodes.61 However, at the time of writing, only 1 randomized study in patients with migraine resistant to medical treatment has been completed (MIST [Migraine Intervention with STARflex Technology]). Definitive results are not yet published and preliminary results indicate no differences in the primary objective (elimination of headache) with differences favoring PFO closure in the secondary objective (50% reduction in days with headache).62 Publication of the definitive MIST results, together with those of other randomized studies currently under way (PREMIUM, ESCAPE, MIST II), will enable us to define the role of PFO closure in patients with migraine.60

Platypnea-Orthodeoxia Syndrome

The definitive treatment for this syndrome is PFO closure.3,56

Closure of PFO in patients with POS can be surgical or percutaneous. Currently, percutaneous closure could be considered the treatment of choice, with an initial success rate of nearly 100% and low incidence of complications.63-65 In our study, percutaneous closure resolved symptoms in all patients and achieved a statistically significant increase in oxygen saturation (82.6% vs 96.1%; P<.001).63

Cryptogenic Stroke

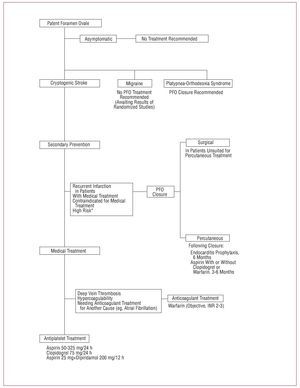

No primary prevention measure is recommended for cryptogenic infarction in patients with PFO. Therapeutic options available for secondary prevention include medical treatment (antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants) and percutaneous or surgical closure. To date, no randomized study has compared medical treatment with percutaneous or surgical closure. Available data comparing antiplatelet drug and anticoagulant treatment are limited. Consequently, no therapy has yet been evaluated definitively and choice of treatment should be on an individual basis, assessing the risks and benefits for each patient.

Medical Treatment

Although medical treatment reduces rate of recurrence, £5% of patients present a second event (death, stroke, transient ischemic events) in the first year, despite medical treatment7 (Table 2). Data on the comparative superiority of antiplatelet drug treatment over anticoagulant treatment are contradictory.

In the WARSS study (Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrence Stroke Study), 2206 patients with stroke (with or without PFO) were randomized to aspirin (325 mg/day) or warfarin (target, INR 1.4-2.8). At 2 year follow-up, rates of recurrence, death or hemorrhage did not differ.66

Similarly, Lausana67 prospectively followed 140 patients with PFO and cryptogenic stroke treated with aspirin (250 mg/day), warfarin (objective, INR=3.5) or surgical closure at the physician´s choice. With a mean 3-year follow-up, rates of recurrent infarction or death did not differ between treatments.

The only published, randomized study comparing aspirin and warfarin in patients with PFO and cryptogenic infarction is PICCS, a subanalysis of WARSS. In PICCS, patients with PFO and cryptogenic infarction were selected and randomized to aspirin (325 mg/day) or warfarin (objective, INR 1.4-2.8). No differences were found in the rate of infarction recurrence in a 2-year follow-up; however, patients treated with warfarin presented a higher rate of minor hemorrhages.45

When evaluating PICCS results, it is important to remember it is a subanalysis of WARSS and was not designed to determine the superiority of one treatment over the other.

On the other hand, some studies suggest a grater benefit in patients treated with warfarin. In a retrospective study of patients with cerebral ischemia and PFO, Cujec et al68 showed patients receiving aspirin or without treatment had a 3-fold greater rate of recurrence than patients receiving warfarin. Mas et al44 enrolled 581 patients with cryptogenic ischemic infarction treated with aspirin (300 mg/day) and in a 4-year follow-up found no differences in rate of recurrence in patients with PFO versus patients without PFO (2.3% vs 4.2%).

Therefore, evidence is insufficient to determine which treatment is superior. However, available data have led the AHA/American Stroke Association69 and the American College of Chest Physicians70 to recommend antiplatelet drug treatment (aspirin 50-325 mg; aspirin 25 mg+dipiridamol 200 mg; clopidogrel 75 mg) as first choice and reserve anticoagulant treatment for patients with deep venous thrombosis or hypercoagulability. However, American Academy of Neurology guidelines71 consider evidence is insufficient to choose between aspirin and warfarin and several authors still consider warfarin the treatment of choice.72

Based on AHA/American Stroke Association69 and American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommendations70 and on data from the only randomized study available,45 we consider the medical treatment of choice in patients with PFO and cryptogenic infarction is aspirin, except in patients with deep venous thrombosis or hypercoagulability, for whom we recommend anticoagulant treatment (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Management schema for patients with patent foramen ovale. *Some authors consider high anatomic risk PFO (ASA, long tunnel, spontaneous right-to-left shunting) is an indication for closure

Percutaneous Treatment

Many studies describe the safety and efficacy of percutaneous PFO closure. With an 86%-100% success rate,73,74 the frequency of recurrent stroke is 0%-3.8% (Table 2), which in most cases reflects incomplete closure or thrombus formation in the device.75 Our results show a 0.9% annual risk of recurrent stroke, and 96% and 90% rates of recurrence- or reintervention-free survival at 1- and 5-year follow-up, respectively.73

These results have been reproduced in patients with PFO and ASA.76 Wah et al77 showed no differences in efficacy, complication rate, elimination of shunting or rate of long-term events in patients with percutaneous closure of PFO or PFO and ASA.

Complications with this procedure are infrequent. One review including 1355 patients showed <1.5% presented major complications (tamponade, death, major hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, or need for surgery), and the rate of minor complications was 7.9% (arrhythmia, fracture or device embolization, air embolism, femoral hematoma, or fistula).78

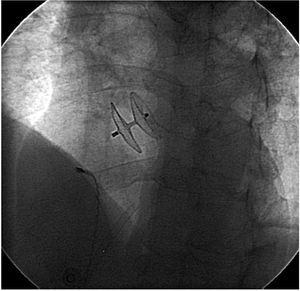

Many devices have been used for percutaneous PFO closure: Amplatzer (AGA Medical Corporation, Plymouth, Minnesota, USA) and Cardioseal (NMT Medical Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, USA) (Table 3 and Figure 7) are the most frequently used. In general, published data indicate both devices prevent recurrence efficiently.79-81

Figure 7. Radioscopic image showing a percutaneous Amplatzer device (AGA Medical Corp, Plymouth, Minnesota, USA) closing patent foramen ovale guided by intracardiac echography.

However, it has been suggested risk of complication could depend on the device used.82 In a study of 1000 consecutive patients with percutaneous PFO closure, 9 different devices were used. Formation of thrombus in the device was most frequent in patients with Cardioseal.83

Similarly, Anzai et al82 describe 22% frequency of thrombus in patients receiving Cardioseal versus 0% in those receiving Amplatzer devices. However, in most patients, detection of thrombus had no clinical implications and the thrombus responded to medical treatment.84

All patients treated with percutaneous devices were recommended 3-6 months of antiplatelet drug treatment (aspirin with or without clopidogrel) following the procedure. In some institutions, this was combined with anticoagulant treatment,84 especially in patients with hypercoagulability. American Heart Association guidelines recommend endocarditis prophylaxis for 6 months after the procedure.85

Most protocols include echocardiography at 1-, 6-and 12-month follow-up. In >95% of patients, closure is complete at 6 months. Persistent shunting that is at least moderate, increases the relative risk of a new ischemic event (RR, 3.4-4.2).75,86 The most appropriate management of these patients with residual shunting is undefined but the possible use of a second percutaneous device to achieve complete closure has been described.87

Medical Treatment Versus Percutaneous Closure

At present, no randomized studies exist that compare medical with percutaneous treatment, although studies like RESPECT and CLOSURE I are currently recruiting.

As mentioned above, medical treatment reduces rate of recurrence but 4.22% (95% CI, 3.43-5.01) of patients present a second event (stroke or transient ischemic event) in the first year despite medical treatment.7 In patients treated with percutaneous closure this rate falls to 1.62% (95% CI, 1.13-2.24) (Table 2).7 These differences in rate of recurrence suggest percutaneous treatment could be the treatment of choice. However, the American Academy of Neurology considers evidence is insufficient for them to take a position on the efficacy of percutaneous or surgical closure, and AHA/American Stroke Association guidelines consider data are insufficient to recommend PFO closure in patients with a first episode but recommend considering closure in patients who, although receiving medical treatment, present a second episode (class IIb, evidence C).69 Various medical societies have called on the general and medical populations to enroll patients in randomized studies to obtain definitive data.88

In the absence of results from randomized studies, in patients with cryptogenic infarction and PFO, percutaneous closure could be considered the treatment of choice for those receiving medical treatment who experience recurrent infarction, are contraindicated for medical treatment and, for some authors, present PFO with high anatomic risk (ASA or hypermobile septum, long tunnel, right-to-left spontaneous shunting)89 (Figure 6).

Other Percutaneous Options

Recently, the use of radio-frequency for percutaneous PFO closure has been described for the first time. Initially, this included 30 patients and in 27 of them the application of radio-frequency was achieved without significant complications. In a 6-month follow-up, complete closure had been achieved in 43% of patients. The authors conclude this is a safe technique requiring new studies to confirm its usefulness.90

Other therapeutic options are under development These include HeartStitch PFO I (Sutura Inc, Fountain Valley, California, USA), based on an automatic suture system, or BioTREK (NMT Medical, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), which uses a totally bioabsorbable device.91

Surgical Treatment

With the introduction of percutaneous closure, surgical closure has become limited to selected cases. Results obtained with percutaneous devices are similar to those obtained with surgery92; in fact, a greater rate of recurrence in patients undergoing surgical closure has been described (4.05%; 95% CI, 2.09-7.07) (Table 2).7 The frequency of complications in surgical closure is greater than in percutaneous closure. Published series92,93 describe a 0%-3.5% rate of postoperative stroke, with 1.5% mortality.94

Other surgical alternatives with results inferior to percutaneous treatment include minimally invasive surgery95 or endoscopic closure.96

Accidental Finding During Cardiac Surgery

The generalized use of TEE during heart surgery procedures has meant finding PFO by chance has become frequent. Data are insufficient to establish management guidelines in this situation.97 However, it is considered that PFO should be closed during the intervention if shunting is highly likely to occur following surgery (ventricular assist device implants, heart transplantation) and this should be borne in mind in patients requiring atriotomy during surgery (mitral valve replacement, tricuspid valve interventions).

CONCLUSIONS

Patent foramen ovale in adults is a frequent finding that, in most patients, presents no clinical implication. However, although data are contradictory, it has been suggested it can be involved as a related or causal factor in embolic stroke, POS or migraine. The treatment of PFO, especially in patients with cryptogenic infarction, is not defined. While we await the results of randomized studies under way at the time of writing, available scientific evidence cannot confirm the superiority of percutaneous/surgical closure over medical treatment (antiplatelet drug/anticoagulant treatment), although some indirect data do support this.

In conclusion, the great prevalence, onclear clinical significance and different therapeutic options available determine the current importance of this entity and will ensure its clinical relevance in the coming years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr Cruz-González would like to thank the Sociedad Española de Cardiología (Spanish Society of Cardiology) for its contribution (The SEC 2007 grant for post-residency research training at overseas centers) and Medtronic Iberia SL for financing his stay at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr Jorge Solis would like to thank the Sociedad Española de Cardiología (The SEC 2007 grant for post-residency research training at overseas centers) for financing his stay at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Daniel Jiménez who collaborated in preparing the figures and to Dr S. Houser who helped collect the photographs.

Correspondence: Dr Ignacio Cruz González,

Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Gray/Bigelow 800,

55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

E-mail: i-cruz@secardiologia.es