To estimate smoking-attributable mortality (SAM) in the regions of Spain among people aged ≥ 35 years in 2017.

MethodsSAM was estimated using a prevalence dependent method based calculating the population attributable fraction. Observed mortality was derived from the National Statistics Institute. The prevalence of smoking by age and sex was based on the Spanish National Health Survey for 2011 and 2017 and the European Survey for 2014. Relative risks were reported from the follow-up of 5 North American cohorts. SAM and population attributable fraction were estimated for each region by age group, sex, and causes of death. Cause-specific and adjusted SAM rates were estimated.

ResultsSmoking caused 53 825 deaths in the population aged ≥ 35 years (12.9% of all-cause mortality). SAM ranged from 10.8% of observed mortality in La Rioja to 15.3% in the Canary Islands. The differences remained after rates were adjusted by age. The highest adjusted SAM rates were observed in Extremadura in men and in the Canary Islands in women. Adjusted SAM rates in men were inversely correlated with those in women. The percentage of total SAM represented by cardiovascular diseases in each region ranged from 21.8% in Castile-La Mancha to 30.3% in Andalusia.

ConclusionsThe distribution of SAM differed among regions. Conducting a detailed region-by-region analysis provides relevant information for health policies aiming to curb the impact of smoking.

Keywords

In 2016, more than 7 million deaths were attributed to smoking worldwide, making it the preventable risk factor with the highest mortality.1 Smoking raises the risk of death associated with an increasingly higher number of conditions. For instance, the 2014 report entitled The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress2 established 4 new causal relationships with smoking: rectal and colon cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, diabetes mellitus, and tuberculosis.

One of the indicators used to characterize the smoking epidemic among the population is smoking prevalence.3 Data from the Spanish National Health Survey have shown that smoking prevalence varies by autonomous community (region). According to these data, in 2016-2017 Galicia was the region with the lowest prevalence (18.3%), while Asturias had the highest (27.7%).4 Since 1987, smoking prevalence has dropped in all regions, but at uneven rates.5 From 2006 to 2017, smoking prevalence dropped 4.4 points on average in Spain; Cantabria, Madrid, and Canary Islands saw larger declines than the Spanish average, whereas Castile and Leon, Extremadura, and Catalonia experienced lower than average drops.4,6

Another indicator used to characterize the smoking epidemic among the population is smoking-attributable mortality (SAM).7 SAM is a simple method for evaluating the impact of smoking on a population. Since 1978, the SAM burden has been estimated in Spain by 21 projects: 8 by region, 11 for Spain as a whole, 1 in a single province of Spain, and 1 in a city. Estimates of SAM for all the regions of Spain are not currently available, and available estimates refer to different time periods.8

The aim of the present study was to estimate SAM in the population aged ≥ 35 years in 2017 in the 17 regions of Spain, using the same information sources and methodology and specifically including the impact of smoking on cardiovascular mortality by region.

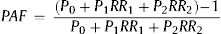

METHODSEstimation methodThe method used to estimate SAM depended on smoking prevalence and calculated the population-attributable fractions (PAFs). This method estimates SAM as the product of observed mortality (OM) and PAF9:

wherein P is smoking prevalence and RR is the relative risk between current smokers (1) and former smokers (2) of dying due to smoking-related diseases, compared with never-smokers (0).

Data sourcesCause-specific OM data were obtained from the National Statistics Institute for the population aged ≥ 35 years in each region for 2017, based on the 10th version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). The latest update proposed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)2 was used to classify smoking-related causes of death as tumors, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, or respiratory diseases. The term “tumors” included tumors of the trachea/bronchus/lung, lips, oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, colon and rectum, liver cells, pancreas, larynx, cervix uteri, urinary bladder, kidney and renal pelvis, and acute myeloid leukemia; cardiovascular diseases included ischemic heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiopulmonary and other heart diseases, cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerosis, aneurysms, and others; and respiratory diseases included influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The respective ICD-10 codes are listed in .

For each region, the prevalence of smokers, former smokers, and never-smokers by sex and age group (35-54, 55-64, 65-74, and ≥ 75 years) were taken from the joint analysis of 3 representative surveys at the national and regional levels: the Spanish Health Survey of 2011-201210 and 2016-20174 and the European Health Survey for Spain in 2014-2015.11 Smoking and former smoking prevalences with the respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) are listed for men and women aged 35 years or older in .

Relative risks (RRs) were obtained from a pooled follow-up analysis of 956 756 patients enrolled in 5 cohort studies in the United States from 2000 to 2010.12

AnalysisThe PAF and SAM were estimated for specific causes and for 3 categories of cause of death —tumors, cardiovascular disease/diabetes, and respiratory disease—by sex and age group (35-54, 55-64, 65-74, and ≥ 75 years) in each region.

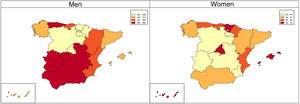

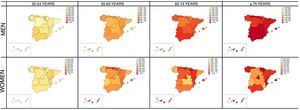

The direct method with the European standard population proposed by Eurostat's task force based on projections for 2011 to 203013 was used to calculate gross SAM rates for each region by sex, cause-specific rates by sex and age group, and age-adjusted rates for men and women. Furthermore, the masculinity ratio (ratio of men to women) was calculated for the adjusted rates in each region. Cause-specific SAM rates are shown on logarithmic scale maps by sex and age group, and adjusted SAM rates are shown on categorized group maps in cause-specific quartiles by sex.

The populations used to calculate the rates were taken from the National Statistics Institute and the European standard population for the Eurostat adjustment.

Estimates were obtained with Stata 14.2, rate adjustments with Epidat 4.2, and spatial representation with QGIS 3.4.

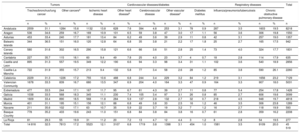

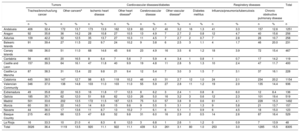

RESULTSIn 2017, smoking caused 53 825 deaths in Spain among the population aged ≥ 35 years, accounting for 12.9% of all-cause mortality in the country that year. Additionally, 84.6% of SAM was men (45 519), and 49.6% were older than 74 years (26 691); 49.7% of SAM was due to tumors (26 774); 66.6% due to lung cancer (17 842); 27.5% due to cardiovascular disease and diabetes (14 289 and 534), and 22.7% due to respiratory diseases (12 228). Table 1 and table 2 list the SAM estimates for the various regions by sex and by cause-of-death category. The region with the smallest difference between SAM for cancer and SAM for cardiovascular disease, whether in men or women, was Andalusia, where 46.8% of SAM among men was due to cancer and 29.3% to cardiovascular conditions, whereas women showed a smaller difference (46.2% and 36.7%, respectively). Conversely, the region with the largest difference in men was the Basque Country (SAM for cancer, 54.8%; SAM for cardiovascular diseases, 25.4%), whereas in women it was Cantabria (63.0% and 21.3%, respectively). Cardiovascular disease-related SAM compared with total SAM for each region was between 21.8% for Castille-La Mancha and 30.3% for Andalusia.

Smoking-attributable mortality over total attributable mortality for men aged ≥ 35 years, according to cause of death, in Spanish regions in 2017

| Tumors | Cardiovascular diseases/diabetes | Respiratory diseases | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea/bronchus/lung cancer | Other cancersa | Ischemic heart disease | Other heart diseaseb | Cerebrovascular disease | Other vascular diseasec | Diabetes mellitus | Influenza/pneumonia/tuberculosis | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Andalusia | 2559 | 31.1 | 1284 | 15.6 | 1132 | 13.8 | 628 | 7.6 | 394 | 4.8 | 253 | 3.1 | 78 | 0.9 | 287 | 3.5 | 1603 | 19.5 | 8218 |

| Aragon | 536 | 34.6 | 259 | 16.7 | 169 | 10.9 | 101 | 6.5 | 59 | 3.8 | 47 | 3.0 | 17 | 1.1 | 56 | 3.6 | 306 | 19.8 | 1550 |

| Asturias | 453 | 33.4 | 240 | 17.7 | 181 | 13.4 | 84 | 6.2 | 49 | 3.6 | 39 | 2.9 | 11 | 0.8 | 42 | 3.1 | 257 | 19.0 | 1357 |

| Balearic Islands | 344 | 36.5 | 151 | 16.0 | 120 | 12.8 | 64 | 6.8 | 35 | 3.8 | 21 | 2.2 | 17 | 1.8 | 25 | 2.7 | 165 | 17.5 | 942 |

| Canary Islands | 580 | 31.6 | 302 | 16.5 | 290 | 15.8 | 121 | 6.6 | 66 | 3.6 | 51 | 2.8 | 25 | 1.4 | 73 | 4.0 | 324 | 17.7 | 1831 |

| Cantabria | 227 | 35.7 | 115 | 18.1 | 60 | 9.4 | 49 | 7.8 | 25 | 4.0 | 23 | 3.7 | 4 | 0.7 | 18 | 2.8 | 114 | 17.9 | 635 |

| Castile and Leon | 895 | 31.3 | 557 | 19.5 | 349 | 12.2 | 190 | 6.6 | 94 | 3.3 | 98 | 3.4 | 31 | 1.1 | 102 | 3.6 | 540 | 18.9 | 2856 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 722 | 31.9 | 355 | 15.7 | 213 | 9.4 | 132 | 5.8 | 77 | 3.4 | 58 | 2.6 | 28 | 1.2 | 85 | 3.8 | 590 | 26.1 | 2260 |

| Catalonia | 2229 | 31.3 | 1226 | 17.2 | 755 | 10.6 | 488 | 6.8 | 244 | 3.4 | 229 | 3.2 | 84 | 1.2 | 219 | 3.1 | 1656 | 23.2 | 7129 |

| Valencian Community | 1678 | 33.3 | 839 | 16.7 | 680 | 13.5 | 347 | 6.9 | 204 | 4.0 | 164 | 3.3 | 47 | 0.9 | 164 | 3.3 | 907 | 18.0 | 5031 |

| Extremadura | 477 | 33.5 | 244 | 17.1 | 167 | 11.7 | 95 | 6.7 | 61 | 4.3 | 39 | 2.7 | 11 | 0.8 | 77 | 5.4 | 254 | 17.8 | 1426 |

| Galicia | 1038 | 33.5 | 568 | 18.3 | 345 | 11.1 | 230 | 7.4 | 105 | 3.4 | 97 | 3.1 | 26 | 0.8 | 85 | 2.7 | 606 | 19.6 | 3099 |

| Madrid | 1609 | 33.4 | 890 | 18.5 | 568 | 11.8 | 284 | 5.9 | 137 | 2.8 | 132 | 2.7 | 32 | 0.7 | 218 | 4.5 | 948 | 19.7 | 4818 |

| Murcia | 401 | 31.1 | 195 | 15.1 | 156 | 12.1 | 88 | 6.8 | 49 | 3.8 | 33 | 2.5 | 16 | 1.2 | 46 | 3.5 | 306 | 23.8 | 1289 |

| Navarre | 211 | 35.6 | 102 | 17.1 | 63 | 10.7 | 35 | 5.9 | 22 | 3.7 | 19 | 3.2 | 7 | 1.2 | 16 | 2.7 | 118 | 19.9 | 593 |

| Basque Country | 778 | 35.2 | 433 | 19.6 | 243 | 11.0 | 151 | 6.8 | 84 | 3.8 | 84 | 3.8 | 16 | 0.7 | 61 | 2.8 | 359 | 16.2 | 2208 |

| La Rioja | 81 | 29.3 | 55 | 19.9 | 31 | 11.2 | 20 | 7.2 | 13 | 4.7 | 12 | 4.4 | 3 | 1.2 | 8 | 2.8 | 54 | 19.5 | 277 |

| Total | 14 816 | 32.5 | 7813 | 17.2 | 5523 | 12.1 | 3107 | 6.8 | 1719 | 3.8 | 1398 | 3.1 | 454 | 1.0 | 1581 | 3.5 | 9109 | 20.0 | 45 519 |

Smoking-attributable mortality over total attributable mortality for women aged ≥ 35 years, according to cause of death, in Spanish regions in 2017

| Tumors | Cardiovascular diseases/diabetes | Respiratory diseases | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea/bronchus/lung cancer | Other cancersa | Ischemic heart disease | Other heart diseaseb | Cerebrovascular disease | Other vascular diseasec | Diabetes mellitus | Influenza/pneumonia/tuberculosis | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Andalusia | 406 | 32.4 | 172 | 13.7 | 173 | 13.9 | 162 | 12.9 | 83 | 6.7 | 40 | 3.2 | 16 | 1.3 | 41 | 3.3 | 157 | 12.6 | 1251 |

| Aragon | 92 | 35.8 | 36 | 14.2 | 28 | 10.8 | 27 | 10.5 | 13 | 4.9 | 7 | 2.7 | 2 | 0.8 | 12 | 4.7 | 40 | 15.6 | 256 |

| Asturias | 109 | 42.2 | 32 | 12.5 | 35 | 13.7 | 27 | 10.3 | 11 | 4.5 | 7 | 2.7 | 2 | 0.7 | 7 | 2.8 | 28 | 10.7 | 258 |

| Balearic Islands | 91 | 39.4 | 27 | 11.5 | 22 | 9.7 | 24 | 10.2 | 9 | 3.8 | 6 | 2.5 | 3 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.7 | 46 | 20.0 | 231 |

| Canary Islands | 168 | 36.0 | 51 | 11.0 | 68 | 14.6 | 45 | 9.6 | 23 | 4.9 | 16 | 3.5 | 6 | 1.2 | 18 | 3.9 | 72 | 15.4 | 467 |

| Cantabria | 56 | 46.5 | 20 | 16.5 | 8 | 6.4 | 7 | 5.6 | 7 | 5.9 | 4 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.7 | 17 | 14.2 | 119 |

| Castile and Leon | 157 | 39.3 | 64 | 16.1 | 47 | 11.8 | 40 | 9.9 | 19 | 4.8 | 11 | 2.8 | 5 | 1.3 | 10 | 2.4 | 47 | 11.7 | 400 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 87 | 38.3 | 31 | 13.4 | 22 | 9.8 | 21 | 9.4 | 12 | 5.4 | 7 | 3.0 | 3 | 1.5 | 7 | 3.1 | 37 | 16.1 | 228 |

| Catalonia | 445 | 38.5 | 147 | 12.7 | 98 | 8.5 | 118 | 10.2 | 46 | 4.0 | 31 | 2.7 | 12 | 1.0 | 24 | 2.1 | 234 | 20.2 | 1154 |

| Valencian Community | 346 | 37.0 | 138 | 14.8 | 103 | 11.0 | 103 | 11.0 | 55 | 5.9 | 27 | 2.8 | 11 | 1.2 | 19 | 2.0 | 135 | 14.4 | 936 |

| Extremadura | 49 | 35.8 | 22 | 16.3 | 16 | 11.8 | 17 | 12.3 | 8 | 6.2 | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.8 | 8 | 6.0 | 12 | 8.4 | 136 |

| Galicia | 185 | 35.7 | 62 | 12.0 | 51 | 9.8 | 62 | 12.0 | 26 | 5.0 | 16 | 3.2 | 3 | 0.6 | 12 | 2.3 | 101 | 19.4 | 519 |

| Madrid | 501 | 33.6 | 202 | 13.5 | 172 | 11.5 | 187 | 12.5 | 75 | 5.0 | 57 | 3.8 | 9 | 0.6 | 61 | 4.1 | 228 | 15.3 | 1492 |

| Murcia | 60 | 38.1 | 22 | 14.0 | 14 | 8.9 | 15 | 9.6 | 9 | 5.5 | 5 | 3.1 | 2 | 1.3 | 9 | 5.8 | 21 | 13.7 | 157 |

| Navarre | 44 | 36.0 | 17 | 13.6 | 11 | 8.7 | 13 | 10.2 | 7 | 6.1 | 6 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.9 | 6 | 4.5 | 18 | 15.0 | 123 |

| Basque Country | 215 | 40.5 | 66 | 12.5 | 47 | 8.8 | 52 | 9.8 | 31 | 6.0 | 16 | 2.9 | 2 | 0.5 | 14 | 2.6 | 87 | 16.4 | 529 |

| La Rioja | 16 | 33.3 | 10 | 21.0 | 4 | 8.3 | 6 | 12.0 | 3 | 6.8 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.9 | 7 | 13.9 | 48 |

| Total | 3026 | 36.4 | 1119 | 13.5 | 920 | 11.1 | 922 | 11.1 | 439 | 5.3 | 261 | 3.1 | 80 | 1.0 | 253 | 3.0 | 1285 | 15.5 | 8305 |

Cause-specific SAM and PAF for each region by sex and age group are listed in .

Regardless of cause or age group, SAM was always higher among men. The highest masculinity ratios were observed in Extremadura (10.5), Castile-La Mancha (9.9), and Murcia (8.2) and the lowest were observed in Madrid (3.2), Canary Islands (3.9), and Balearic Islands (4.1).

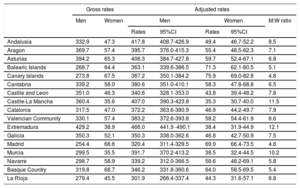

After adjustment of SAM rates by age, Extremadura, Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha, and Asturias were the regions with the highest rates among men, and Canary Islands, Balearic Islands, Madrid, and the Basque Country had the highest rates among women (figure 1 and table 3). In the regions, adjusted SAM rates for men correlated negatively with the rates for women (Spearman correlation coefficient=−0.34; 95%CI, −0.35 to −0.21) ().

Gross and adjusted smoking-attributable mortality* per 100 000 inhabitants of the population aged ≥ 35 years in each region and men-to-women ratio for the adjusted rates in 2017

| Gross rates | Adjusted rates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | M:W ratio | |||

| Rates | 95%CI | Rates | 95%CI | ||||

| Andalusia | 332.9 | 47.3 | 417.8 | 408.7-426.9 | 49.4 | 46.7-52.2 | 8.5 |

| Aragon | 369.7 | 57.4 | 395.7 | 376.0-415.3 | 55.4 | 48.5-62.3 | 7.1 |

| Asturias | 394.2 | 65.3 | 406.3 | 384.7-427.8 | 59.7 | 52.4-67.1 | 6.8 |

| Balearic Islands | 268.7 | 64.4 | 363.1 | 339.6-386.5 | 71.3 | 62.1-80.5 | 5.1 |

| Canary Islands | 273.8 | 67.5 | 367.2 | 350.1-384.2 | 75.9 | 69.0-82.8 | 4.8 |

| Cantabria | 339.2 | 58.0 | 380.6 | 351.0-410.1 | 58.3 | 47.8-68.8 | 6.5 |

| Castile and Leon | 351.0 | 46.3 | 340.6 | 328.1-353.0 | 43.8 | 39.4-48.2 | 7.8 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 360.4 | 35.6 | 407.0 | 390.3-423.8 | 35.3 | 30.7-40.0 | 11.5 |

| Catalonia | 317.5 | 47.0 | 372.2 | 363.6-380.9 | 46.9 | 44.2-49.7 | 7.9 |

| Valencian Community | 330.1 | 57.4 | 383.2 | 372.6-393.8 | 58.2 | 54.4-61.9 | 6.6 |

| Extremadura | 429.2 | 38.9 | 466.0 | 441.9 -490.1 | 38.4 | 31.9-44.9 | 12.1 |

| Galicia | 350.3 | 52.1 | 350.3 | 338.0-362.6 | 46.8 | 42.7-50.9 | 7.5 |

| Madrid | 254.4 | 68.6 | 320.4 | 311.4-329.5 | 69.9 | 66.4-73.5 | 4.6 |

| Murcia | 299.5 | 35.5 | 391.7 | 370.2-413.2 | 38.5 | 32.4-44.5 | 10.2 |

| Navarre | 298.7 | 58.9 | 339.2 | 312.0-366.5 | 58.6 | 48.2-69.1 | 5.8 |

| Basque Country | 319.8 | 68.7 | 346.2 | 331.8-360.6 | 64.0 | 58.5-69.5 | 5.4 |

| La Rioja | 279.4 | 45.5 | 301.9 | 266.4-337.4 | 44.3 | 31.6-57.1 | 6.8 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; M, men; W, women.

Age-adjusted SAM rate according to the direct method with the standard European population proposed by Eurostat's Task Force based on projections for 2011-2030.13

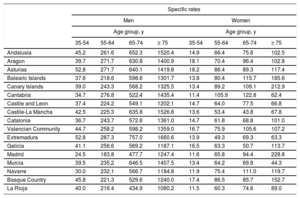

The specific SAM rate for men rises with age, but this was not seen among women in all regions (figure 2). Extremadura, Andalusia, and Asturias were the regions with the highest SAM-specific rates for men, whereas the highest rates in women were seen in the Basque Country, Balearic Islands, and Canary Islands (table 4).

Smoking-attributable mortality per 100 000 inhabitants in each region for men and women and according to age group (35-54, 55-64, 65-74, and ≥ 75 years) in 2017

| Specific rates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Age group, y | Age group, y | |||||||

| 35-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | ≥ 75 | 35-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | ≥ 75 | |

| Andalusia | 45.2 | 261.6 | 652.3 | 1520.4 | 14.9 | 66.4 | 75.8 | 102.5 |

| Aragon | 39.7 | 271.7 | 630.8 | 1400.9 | 18.1 | 70.4 | 96.4 | 102.8 |

| Asturias | 52.8 | 271.7 | 640.1 | 1419.8 | 18.2 | 86.4 | 89.3 | 117.4 |

| Balearic Islands | 37.6 | 218.6 | 598.6 | 1301.7 | 13.8 | 80.4 | 115.7 | 185.6 |

| Canary Islands | 39.0 | 243.3 | 568.2 | 1325.5 | 13.4 | 89.2 | 109.1 | 212.9 |

| Cantabria | 34.7 | 276.8 | 522.4 | 1435.4 | 11.4 | 105.9 | 122.8 | 62.4 |

| Castile and Leon | 37.4 | 224.2 | 549.1 | 1202.1 | 14.7 | 64.0 | 77.5 | 66.8 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 42.5 | 225.3 | 635.8 | 1526.8 | 13.6 | 53.4 | 43.8 | 67.8 |

| Catalonia | 36.7 | 243.7 | 572.6 | 1361.0 | 14.7 | 61.8 | 68.8 | 101.0 |

| Valencian Community | 44.7 | 258.2 | 598.2 | 1359.0 | 16.7 | 75.9 | 105.6 | 107.2 |

| Extremadura | 52.8 | 287.3 | 757.0 | 1660.6 | 13.9 | 49.3 | 69.3 | 63.3 |

| Galicia | 41.1 | 256.6 | 569.2 | 1187.1 | 16.5 | 63.3 | 50.7 | 113.7 |

| Madrid | 24.5 | 183.8 | 477.7 | 1247.4 | 11.6 | 65.8 | 94.4 | 228.8 |

| Murcia | 39.5 | 235.2 | 646.5 | 1407.5 | 13.4 | 64.2 | 69.8 | 44.3 |

| Navarre | 30.0 | 232.1 | 566.7 | 1184.8 | 11.9 | 75.4 | 111.0 | 119.7 |

| Basque Country | 45.8 | 221.3 | 529.6 | 1240.0 | 17.4 | 86.5 | 85.7 | 152.7 |

| La Rioja | 40.0 | 216.4 | 434.9 | 1080.2 | 11.5 | 60.3 | 74.6 | 89.0 |

The SAM compared with total OM varied among the regions from 10.8% in La Rioja to 15.3% in the Canary Islands. This variation was also seen as a function of sex. In men, SAM was highest in Extremadura (24.6%) and lowest in La Rioja (18.4%). In women, it was highest in Canary Islands (6.6%) and lowest in Castile-La Mancha (2.3%) (figure 3).

Extremadura (10.2), Castile-La Mancha (9.6), and Murcia (7.8) had the highest masculinity ratios in the SAM percentages, while the lowest were observed in Canary Islands (3.5), Balearic Islands (3.9), and the Basque Country (4.2) (figure 4).

DISCUSSIONThis study is the first to estimate SAM for a single year in all Spanish regions, using the same information sources and a common methodology. The results show that the impact of smoking on mortality varied among the regions. The category of causes with the highest SAM was tumors, followed by cardiovascular disease/diabetes, and respiratory disease. Once the SAM rate was adjusted for age, the highest rates among men were observed in Extremadura, Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha, and Asturias, and among women in Canary Islands, Balearic Islands, Madrid, and the Basque Country. Andalusia is the region where smoking had the greatest impact on SAM due to cardiovascular diseases.

Any comparison of SAM estimates obtained in this study with previous estimates available for Galicia,14,15 Extremadura,16 Castile-La Mancha,17 Castile and Leon,18 Canary Islands,19,20 and Madrid21 should be made carefully, as differences in the RRs used, age groups analyzed, or causes included should be taken into account. For instance, point estimates of the RRs used in these analyses, compared with those used in previous studies,22 showed little change among men but were higher among women. The estimates were also influenced by a more detailed breakdown in the age groups and the inclusion of 4 causes of mortality not previously analyzed.2 Moderate increases in the weight of SAM compared with total OM were seen in Castile and Leon from 9.9% (1995) to 15.3% (2017), in Canary Islands from 14.9% (1993) to 13.6% (2017), and in Extremadura from 11.7% (1993) to 13.6% (2017).14,16,18 In these regions, smoking prevalence was unchanged among women, but was lower among men compared with 2017. For example, smoking prevalence among men dropped from 56.5% in 199316 to 32.9% in Extremadura, from 53.3% in 199518 in Castile and Leon to 28.5%, and from 47.5% in 199319 to 28.8% in the Canary Islands. Consequently, the increase in the weight of SAM in OM may be due to various factors linked to the estimation method, among them the age as of which SAM was estimated, which varied between studies. Previous studies for Castile and Leon and for Extremadura obtained the population-attributable mortality for age ≥ 15 years, which means that the proportion of total OM was lower than the proportion obtained from estimates in the population aged ≥ 35 years.16,18 The Canary Islands study did not report the age used to perform the estimates.19

The percentage of SAM vs OM in the population aged 35 years or older dropped from 12.5% (2001-2006)14 to 11.4% in Galicia, from 18.7% (1987 and 1997)17 to 12.4% in Castile-La Mancha, and from 15.9% (1992-1998)21 to 13.6% in Madrid. This decrease can be explained by the decline in smoking prevalence in 2017 compared with prevalences used in prior estimates in Galicia,23 Castile-La Mancha,5,24 and Madrid.5,25

In 2017, similar to previous studies, the causes with the highest SAM were tumors, followed by cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases.16,17,21 Based on the specific causes of mortality, lung cancer accounted for the highest SAM, followed by COPD. Since 2003, lung cancer-related OM among Spanish women increased 2-fold,26 which is reflected in the results obtained, and is currently the main cause of SAM among women in all regions.

In Spain, substantial decreases were observed in gross mortality rates for ischemic heart disease (relative decrease of −32% in men and −37% in women), cardiovascular disease (−39% and −43%), and COPD (−34% and −44%) in the past 20 years (1999-2018), whereas mortality due to the types of cancer associated with smoking in this study increased by 9% in men and by 17% in women.27 This differing trend in mortality due to major categories of smoking-related diseases has led to an increased relative weight of cancer in total SAM in recent years: in 2000 to 2004, cancer accounted for 44.8% of SAM in men and 34.3% in women, and in 2010 to 2014, 50.2% and 47.9%, respectively. Conversely, the relative proportion of cardiovascular diseases in SAM has dropped in men from 31.6% in 2000 to 2004 to 24.9% in 2010 to 2014, and in women from 41.8% to 32.6%.28 To interpret these changes, it is necessary to consider the large differences in time between exposure and outcome in these disease categories, which is much longer in cancer29 than in cardiovascular diseases, where the effects are observed more rapidly.30 In 2017, cancer accounted for a larger portion of SAM than cardiovascular disease in all regions and in both men and women, although there were notable differences in the size of the relative contribution, resulting in an uneven distribution of these diseases in the various Spanish regions. Andalusia, a region with historically high cardiovascular mortality rates, has the largest relative proportion of these diseases in SAM, whereas cancer had a higher relative weight in regions in northern Spain, such as Cantabria or the Basque Country.

The gender perspective has major implications for SAM analysis when designing public health interventions, as men and women show different patterns in smoking prevalence and mortality. The various trends seen in the smoking epidemic based on the economic development of each region may explain the differences observed in the age-adjusted SAM rate in men,31 whereas differences in women may be related to educational levels.32

The pattern of negative or inverse relationship in SAM according to sex and region (as the SAM rate for men increases, the rate for women decreases) indicates differing trends for the smoking epidemic in each region. Because many biological, psychological, and social factors have been associated with sex-related differences, not only with uneven trends in smoking prevalence33 but also with smoking discontinuation or cessation,34 additional research should be undertaken and considered when drawing up smoking prevention and monitoring policies.

Although estimates allow smoking impact in the various regions to be compared for the same time period, there are several limitations. These limitations include those associated with how close the years of smoking prevalence estimates are to the year of the OM, which does not ensure that exposure is sufficiently earlier than the effect. This may mean that SAM is underestimated and varies according to the cause of death, related to the decrease of smoking prevalences in Spain in recent decades.35 Moreover, smoking prevalences are derived from self-reported data, which may mean that smoking habits are concealed and, consequently, prevalences are underestimated.36,37 To estimate smoking prevalence, results were pooled from 3 surveys, each of insufficient sample size to estimate specific prevalences by region, sex, and age group. The present analysis did not estimate SAM in Ceuta and Melilla, as prevalence estimates were imprecise. The RRs are derived from cohort studies carried out in a US population, where smoking trends have been different from those seen in Spain. However, these risks represent the best available evidence for evaluating the excess risk of death associated with smoking, because they are derived from the follow-up of a large number of people over long periods. Additionally, the RRs used have not been adjusted for potential confounding factors, although the variation in the estimate when applying adjusted RRs is small,38 and a relative reduction of 1% in SAM has been estimated.39

CONCLUSIONSIn 2017, a total of 53 825 deaths were attributed to smoking, accounting for 12.9% of all-cause mortality that year. The SAM portion of total OM is unequal between regions and varies from 10.8% in La Rioja to 15.3% in the Canary Islands. Among men, the weight of SAM in total OM ranged from 24.6% in Extremadura to 18.4% in La Rioja; among women, the figures were 6.6% in Canary Islands to 2.3% in Castile-La Mancha. In all regions, SAM was higher in men. Among the major causes of death, cardiovascular diseases ranked second after tumors in SAM. Andalusia was the region where smoking had the highest impact on mortality due to cardiovascular disease. Although SAM due to cardiovascular disease has dropped considerably in recent years, partly because tumors play a more important role due to a phenomenon of competitive mortality, smoking is still a highly relevant risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

FUNDINGThis project was funded by the Carlos III Health Institute (No. PI19/00288). The sponsors did not participate in the study in any way.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSThis study was part of the research undertaken by Julia Rey for her doctoral degree.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Smoking is an avoidable risk factor increasingly found to be associated with more diseases. One of the indicators used to characterize the smoking epidemic among the population is smoking-attributable mortality. Only a few studies in Spain have estimated region-specific smoking-attributable mortality. To date, attributable mortality estimates are only available for 6 regions, and all refer to different time points. The latest estimate was for 2001 to 2006 in Galicia.

- –

This is the first study to estimate smoking-attributable mortality in 17 Spanish regions for the same time period, using the same information sources and a common methodology. Smoking causes approximately 150 deaths a day in Spain. Once again, smoking is confirmed to be an important cardiovascular risk factor, leading to more than 14 000 deaths per year due to cardiovascular disease. The data describe the impact of smoking in each region, making it easier to plan and manage health policies intended to curb smoking, according to the needs of each region.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2020.10.023