To present the annual report of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology on the activity data for 2017.

MethodsData were voluntarily provided by Spanish centers with a catheterization laboratory. The information was introduced online and was analyzed by the Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology.

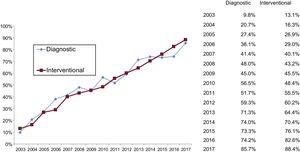

ResultsIn 2017, data were reported by 107 hospitals, of which 82 are public. A total of 154 218 diagnostic procedures (138 448 coronary angiograms) were performed (2.2% increase vs 2016). The use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques significantly increased, especially that of pressure wire (23.2% vs 2016, n=7003). In 2017, the number of percutaneous coronary interventions rose to 70 928 (3.2% increase), of which 21 395 interventional procedures were performed in the acute myocardial infarction setting. A total of 105 529 stents were implanted, of which 90.3% were drug-eluting stents (6% increase). Radial access was used in 85.7% of diagnostic procedures and in 88.4% of interventional procedures. The number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations continued to increase (28.2% increase, n=2821), as did the number of left atrial appendage closures (14.8% increase, n=582) and percutaneous mitral valve repair procedures (14.1% increase, n=270).

ConclusionsDiagnostic and therapeutic procedures in acute myocardial infarction increased in 2017. The use of the radial approach and drug-eluting stents also increased in therapeutic procedures. The number of structural procedures rose significantly compared with previous years.

Keywords

As is the case each year, one of the fundamental tasks of the Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology is the collection of activity data from Spanish catheterization laboratories to prepare the annual registry. This work, which has been carried out uninterrupted since 1990,1–26 allows an overall view of changes over time in interventional cardiology and helps to detect opportunities for improvement.

The growth and diversification of the registry has paralleled the increase in such activity in the different units of the country; this year, new variables have been introduced to account for recently developed techniques and procedures, in both percutaneous coronary interventions and structural interventions, and those that are outdated have been simplified or modified. Data are submitted on a voluntary basis via an online database to facilitate participation. Data cleaning was performed by the members of both the steering committee and the working group, given that the preliminary results were presented at the annual meeting of the working group, which took place in Gijón, Spain, on June 7th and 8th, 2018.

The value of our registry of annual activity lies in its ability to reveal the degree of implementation of percutaneous techniques both in Spain itself and in relation to the international setting, as well as to evaluate and compare the development of interventional cardiology in the different autonomous communities. Even with the limitations of a voluntary activity registry,27 the free availability of the data promotes understanding of the actual distribution of resources and the trends in the use of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Therefore, these data serve as a reference to guide interventions to improve health care in multiple ways, via research, prevention, treatment, and resource distribution. Moreover, the combined effort of the interventional cardiology field to record its activity exemplifies, besides its transparency, its commitment to continuously improving a health care system that is defined by its equity and universality.

This article represents the 27th report on interventional activity in Spain and collects activity from both public and private centers corresponding to 2017.

METHODSIn the present registry, data were collected on the diagnostic and cardiac interventional activity of most Spanish hospitals in 2017. Data collection was voluntary and was not audited. Anomalous data or data that deviated from the trend observed in a hospital in recent years were referred back to the responsible researcher from the center for reassessment. Data were collected via a standard electronic questionnaire that could be accessed, completed, and consulted through the website of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology.28 The data were analyzed by the Tride company, in conjunction with a member of the committee. The data were compared with those obtained in previous years by the working group steering committee. The results are published in this article, but a preliminary draft was presented as a slideshow at the working group's annual meeting.

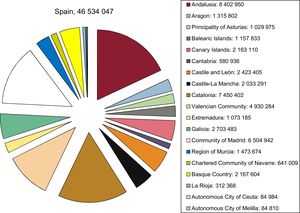

As in previous years, the population-based calculations for both Spain and each autonomous community were based on the population estimates of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics up until July 1st, 2017, as published online.29 The Spanish population was estimated to have increased to 46 534 047 inhabitants (Figure 1). As in recent years, the number of procedures per million population for the country as a whole was calculated using the total population.

Population of Spain on July 1st, 2017. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.29

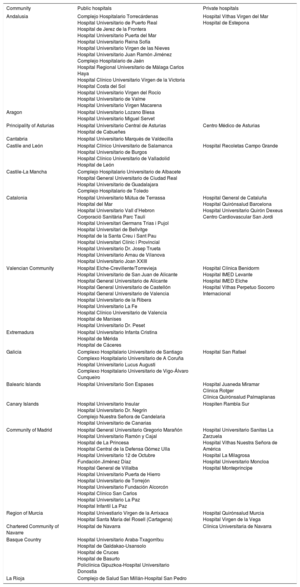

A total of 107 hospitals performing interventional activity participated in this registry; most of these centers (n=82) were public (Appendix). This number effectively reflects the activity in Spain, with most of the volume concentrated in centers with public funding. Note that the number of centers reporting their data has remained stable in recent years, allowing sufficiently reliable comparisons with data from previous years. There were 225 catheterization laboratories: 142 (63.1%) were exclusively for cardiac catheterization, 57 (25.3%) were shared rooms, and 26 (11.5%) were hybrid rooms.

A nominal record of active interventional cardiologists was requested, with 477 such personnel in the 107 centers (413 of them accredited). Of the total number of interventional cardiologists recorded, 88 (18.4%) were women. Of the nursing staff, there were 679 registered nurses and 94 radiology technicians.

Diagnostic ProceduresIn 2017, 154 218 diagnostic studies were performed, a number similar to that recorded in 2016 (154 362), indicating that such activity has plateaued. Of these procedures, 138 448 (89.7%) were coronary angiograms (2.3% more than in 2016) and 10 332 diagnostic studies (6.7%) were performed on valvular patients. There was a significant increase in the radial approach, used in 85.7% of all diagnoses made this year (an 11.5% increase vs 2016).

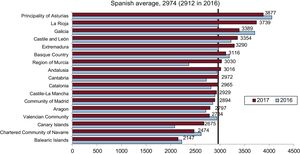

The average number of diagnostic studies was 3311 procedures per million population in Spain; in terms of coronary angiography, the Spanish average was 2974 per million, slightly higher than that registered in 2016 (2912). The distribution by autonomous community of coronary angiograms per million population is shown in Figure 2. Regarding the diagnostic activity by center, 69 centers performed more than 1000 coronary angiograms (2 more than in 2016) and 20 performed more than 2000 (similar to the previous year).

Coronary angiograms per million population. Spanish average and total by autonomous community in 2016 and 2017. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.29

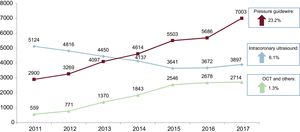

Regarding intracoronary diagnostic techniques, there was a marked increase–23.2%–in the use of the pressure guidewire vs 2016 (7003 cases in 2017 vs 5686 in 2016). The gradual decrease in the use of intracoronary ultrasound in favor of optical coherence tomography in recent years stopped in 2016 and even reversed in 2017, with a 6.1% increase. However, the use of optical coherence tomography, whose popularity has grown considerably since its introduction, seems to have stagnated in the last 2 years, with a slight annual increment of 1.3% in 2017. The changes in intracoronary diagnostic techniques in recent years are shown in Figure 3.

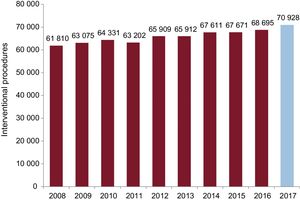

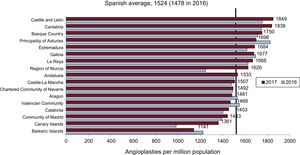

Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsA total of 70 928 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) were reported in 2017, which is 3.2% higher than the 68 695 PCIs in 2016. The changes in PCI over time are shown in Figure 4. There were 1524 PCIs per million population (vs 1478 in 2016 and 1466 in 2015). PCIs numbered 13 966 in women and 16 068 in those older than 75 years of age. The PCI/coronary angiography ratio remains at 0.5, similar to that of 2016.

Regarding complex interventions, there was a notable increase in procedures performed on the left main vessel, with a total of 3661 (3439 in 2016), which comprised PCI of the unprotected left main trunk in 84%. Procedures recorded as involving multivessel disease accounted for 23% of all procedures (30% in 2015 and 24.8% in 2016). Lesions considered by operators as chronic total occlusions numbered 2346 (3.3% of all PCIs), and 6645 bifurcation lesions (9.3% of all PCIs) were addressed. However, this figure must be taken with caution, given that the response percentage was low among the different centers and there is a risk of underestimation. Finally, the number of restenosis interventions fell to 2812 (3191 in 2016). The progressive decrease in recent years in this procedure parallels the greater use of drug-eluting stents, as shown below.

As with diagnostic activity, the radial approach predominates in PCIs and reaches levels placing Spain at the forefront of this field, with 88.4% of interventional procedures performed via radial access (82.6% in 2016). The changes over time since its introduction in 2003 are shown in Figure 5, from an equal standing with the femoral approach in 2010 to its current dominance.

The distribution by community of the 1524 PCIs per million population in Spain is shown in Figure 6. Regarding the distribution per hospital in 2017, 25 centers performed more than 1000 angioplasties (3 more than in 2016), 49 performed between 500 and 1000, and 20 centers performed less than 250 PCIs. This year, 66% of the centers reported the immediate outcome variables: a successful outcome without complications was reported for 94.8%; 1% reported severe complications (death, acute myocardial infarction [AMI], or the need for urgent cardiac surgery); and only 0.3% reported intraprocedural death.

Percutaneous coronary interventions per million population, Spanish average and total by autonomous community in 2016 and 2017. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.29

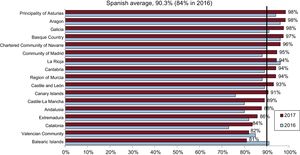

Implanted stents numbered 105 529 in 2017, which was a slight increase vs 2016 (104 628 stents). The stent/procedure ratio was 1.5 (1.6 in 2016). A noteworthy finding is the 6% increase in the percentage of drug-eluting stents implanted vs the total number of stents, reaching 90.3% (95 253) vs 84.4% (88 344) in 2016. When the use of drug-eluting stents was analyzed by community (Figure 7), a generalized increase was observed. Notably, most communities were above the Spanish average, with these stents already comprising 98% of all stents implanted, a by no means insignificant number. The number of procedures with bioabsorbable devices has plummeted, with 529 such procedures in 2017 (0.5% of the total) vs 1610 in 2016 (1.5%). The number of procedures with dedicated bifurcation stents also fell (210 cases [0.2%] vs 240 in 2016), as well as those with self-expanding stents, with only 37 cases (0.04%). There was a slight increase in the number of procedures involving polymer-free stents (4754 [4.5%] vs 3368 [3.2%] in 2016).

Other Devices and Procedures Used in Percutaneous Coronary InterventionThe first notable finding in this section is the increase in the use of plaque modification devices for both rotational atherectomy, which reached its highest level in the last 10 years with 1324 reported cases (1171 in 2016 and 1262 in 2015), and laser atherectomy, currently performed in a small number of centers but with almost triple the number of procedures vs the previous year (58 in 2017 vs 21 in 2016). The use of special balloons, such as the cutting balloon, fell slightly to 2096 (2446 in 2016) due to the progressive increase in the use of the scoring balloon: 1931 (1520 in 2016). The use of drug-eluting balloons also slightly increased (2664 this year vs 2575 in 2016).

In 2017, there was a significant increase in the implantation of short-term circulatory assist devices during complex coronary interventions. The use was reported of 1129 intra-aortic balloon pumps (vs 984 in 2016), 68 extracorporeal membrane oxygenators (vs 40 in 2016), and 106 Impella devices (vs 59 in 2016).

Regarding other coronary intervention procedures, there was a significant increase in the number of septal ablations (96 in 2017 vs 67 in 2016) and, to a lesser extent, in coronary fistula closures (33 in 2017 vs 26 in 2016).

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Acute Myocardial InfarctionThe recent trend for an increase in the number of PCIs in AMI continued with a 3% increment (21 395 interventions in AMI in 2017 vs 20 588 in 2016). This increase is due to the higher number of primary angioplasties, 7.4% more than in 2016 (17 785 vs 16 554), representing 83.1% of all PCIs in AMI. In accordance with the definitions of the European clinical practice guidelines,30 the treatment option “facilitated angioplasty”, currently not indicated, has been withdrawn. Regarding the pharmacoinvasive strategy, 937 rescue PCIs after fibrinolysis administration were recorded (4.7% of the total number of AMI procedures), as well as 1726 delayed or elective PCIs (8% of the total number of AMI procedures).

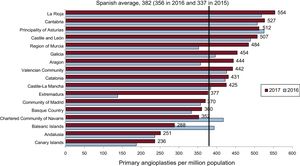

Primary PCIs accounted for 24.7% of all angioplasties. The average number of primary PCIs per million population in Spain was 382 (356 in 2016 and 337 in 2015). Regarding the rate of primary angioplasty by autonomous community (Figure 8), there was a generalized increase, although it was especially marked in Extremadura, Galicia, Aragon, Region of Murcia, and Castile-La Mancha. However, there may be a bias because some hospitals may not have introduced their data; these figures should thus be taken with caution. The number of centers performing more than 300 primary PCIs decreased (from 28 in 2016 to 21 in 2017) due to an increase in centers performing between 200 and 300 (22 in 2017 vs 18 in 2016), whereas the number of centers performing fewer than 50 primary PCIs decreased from 25 in 2016 to 21 in 2017. Additionally, the number of centers with a 24-hour AMI team increased this year, from 82 in 2016 to 88 in 2017.

In terms of the technical aspects of AMI treatment, the use of the radial approach, in line with the above results, increased by 13% and was applied in 87% of PCIs in AMI. The same occurred with the use of drug-eluting stents to treat infarction, which reached 92% (85% in 2016). The use of abciximab as adjuvant treatment during PCI decreased by 3.6% vs last year (it is used in 17.2% of cases). Finally, the number of procedures using thrombus extractor devices fell slightly, from 34% in 2016 to 32% in 2017.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Structural Heart DiseaseIn 2017, 481 valvuloplasties were recorded in adults, 52% on the aortic valve, 43% on the mitral valve, and 5% on the pulmonary valve. The tendency continued for an increased number of isolated aortic valvuloplasties, not related to the implantation of a transcatheter aortic valve prosthesis, with 252 procedures in 2017 (231 in 2016). Success was achieved in 249 patients (98.8%); 3 cases with complications were reported, all of them severe aortic insufficiency. In contrast, the number of mitral valvuloplasties continued to decrease, with 202 reported this year (233 in 2016). The technique was successful in 196 patients (97%) and there were 6 cases of severe mitral regurgitation, with no cases of cardiac tamponade, stroke, or death.

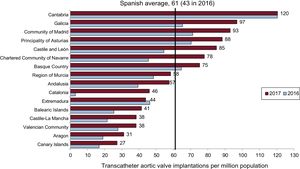

After a marked increase in the number of procedures vs the previous year, transcatheter aortic valve implantation is now one of the main protagonists in structural heart interventions. Thus, in 2017, 2821 procedures were recorded vs 2026 in 2016 (a 28.2% increase), which represents an average of 61 procedures per million population (vs 43 in 2016). If this growth is assessed by autonomous community (Figure 9), there was a substantial increase in all communities vs 2016, with Cantabria, Galicia, the Principality of Asturias, Community of Madrid, Castile and León, the Chartered Community of Navarre, and the Basque Country above the Spanish average. Transcatheter aortic valve implantations were performed in 1625 patients older than 80 years (57.6%) and most patients had a contraindication to surgery or high surgical risk (61% vs 63.3% in 2016), with a slight increase vs the previous year in the percentage of patients with intermediate risk (20% vs 17.5%); no indication was specified for the remainder. Regarding the type of prosthesis used, the expandable balloon valve was used in 1248 cases (44.2%) and 1291 cases involved a self-expanding valve (45.7%); in 282 procedures, the type of valve used was not specified. The most frequently used access route was the transfemoral route (2484, 88% of cases), followed by the transapical (n=73), representing a fall vs the previous year (2.5% of cases vs 3.8% in 2016). Regarding the in-hospital outcomes, 147 major intraprocedural complications (5.3%) were reported; 0.4% (12 cases) required conversion to surgery (urgent conversion in 10 of them). Death was reported during hospitalization in 13 cases (0.5%). A total of 280 patients (10.1%) required definitive pacemaker implantation (a reduction of 2% vs 2016). Nine cases of mitral “valve-in-valve” procedures were reported, as well as 6 in the tricuspid position (vs 2 in 2016).

Regarding the treatment of paravalvular leaks, there was an increase in the closure of aortic leaks, with a total of 72 in 2017 (vs 49 in 2016). However, the closure of mitral leaks decreased, with 118 cases in 2017 vs 138 in 2016. Five cases with complications were reported.

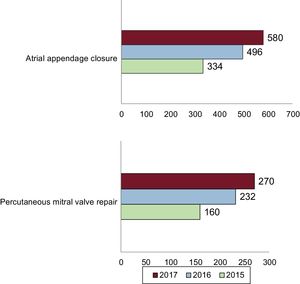

In 2017, 582 cases of left atrial appendage closure were performed, a 14.8% increase vs 2016 (496 cases) (Figure 10). Therefore, it is another of the burgeoning techniques. It should also be noted that significantly fewer complications (tamponade, embolism, or death) were reported than in the previous year (1% in 2017 vs 4.5% in 2016). The closures were performed with a disc-and-lobe device in 399 patients (69% of the total) and with a 1-piece device in 117 (20% of the total); in the remaining cases, the type of closure was not specified.

Another noteworthy finding is the significant increase in percutaneous valvular repair with the MitraClip system in 2017 (Figure 10). The registry recorded 270 cases of mitral valve repair (232 in 2016, a 14.1% increase), with a total of 374 clips (number of clips per procedure, 1.4). The following indications were reported: 67.3% functional mitral regurgitations, 20.2% organic, and 12.2% mixed. Regarding the outcomes, the mitral regurgitation was reduced to grade 1 in 132 patients (63%) and to grade 2 in 68 (32%); no improvement was achieved in only 4 cases (1.1%). The procedure is safe, with complications reported in only 4 patients. In 2017, the MitraClip system was used for the first time for the compassionate treatment of tricuspid regurgitation, with success in all cases.

There were 38 cases of endovascular aortic repair and 24 of renal denervation (33 in 2016). In 2017, new variables were included to reflect all of the newly introduced techniques. Thus, the first procedure with a coronary sinus reducer device was performed and the first 3 interventions with the V-Wave device. Previously omitted techniques were included, such as interventional procedures in pulmonary thromboembolism (89 cases reported in 20 centers) and balloon pericardiotomy (49 cases reported in 16 centers).

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Adult Congenital Heart DiseaseThe most noteworthy finding in this section is the significant growth in the number of permeable foramen ovale closures, from 201 cases in 2016 to 284 in 2017, a 29% increase. No major complications or implant failures were reported with this technique. The number of interatrial communication closures slightly increased vs last year (294 in 2017 vs 271 in 2016); there were 8 cases of failure without major complications. There were 25 patent ductus arteriosus closures (37 in 2016) and 11 ventricular septal defect closures (21 in 2016). A total of 22 pulmonary valvuloplasties were performed (29 in 2016) and a pulmonary valve was implanted in 32 cases (31 in 2016), with a success rate of 94%.

DISCUSSIONThe activity recorded in 2017 clearly reflects the changes over time in interventional cardiology in Spain and allows us to envisage the future path for this field. PCI activity has shown slow but steady growth and a clear qualitative leap, whose strongest indicator is the increase in all intracoronary diagnostic techniques and the high percentage of radial access. In structural heart interventions, the overall number of techniques implemented in recent years has increased and the significant jump in the number of procedures has reduced the previous prevailing gap with neighboring countries in this field.

With regard to coronary diagnostic activity, the greater use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques stands out, as already mentioned. Particularly relevant is the more than 20% growth in the use of the pressure guidewire, which nowadays is a fundamental tool for decision-making in the catheterization laboratory, supported by the excellent results obtained both in chronic patients and in the setting of AMI.31,32 In addition, the increased use of nonhyperemic indices, which facilitate and expedite the procedure and have recently been validated in 2 large studies,33,34 may have contributed to this marked growth. Another important finding is the increase, for the second year in a row, in intracoronary ultrasound, which seems to parallel the increase in percutaneous treatment of the coronary artery.

PCI activity slightly increased vs 2016: a rate of 1524 PCIs per million population was reached, although this figure is still much lower than the recently published European average (2300 per million).35 Various indicators point to a growth in complex PCIs; for example, the increased use of rotational and laser atherectomy and of cutting balloons, as well as the jump in the use of short-term ventricular assistance as procedural support. Moreover, there was another annual increase in the number of PCIs in the unprotected left main trunk, with encouraging results, in line with those obtained in the recently published EXCEL trial.36 The growth in the number of interventional procedures has been reflected in a higher number of stent implantations, with a very high penetration rate for the drug-eluting stent (6% more than in 2016). This type of stent already accounts for 90.3% of all stents; this figure places Spain above the recently reported European average.35

The growth in interventional procedures in AMI, due to an increase in the number of primary angioplasties (7.4% higher than in 2016), is one of the best indicators of interventional activity quality in Spain. With an average of 382 primary PCIs per million population, our country has gone from occupying one of the last positions to approaching the 455 primary PCIs per million population recently reported as the European average.35

Undoubtedly, another of the indicators of health care quality in Spanish hospitals, which places Spain at the head of the surrounding countries, is the predominant use of the radial approach for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. After an exponential growth since its introduction in the early 2000s, rates of 85% in diagnostic procedures and 88% in PCI have been reached, especially in one of the clearest beneficial settings, namely angioplasty for AMI.37

Another notable finding in the annual activity data is the growth in structural heart interventions, especially in transcatheter aortic valve implantation. The irrefutable evidence in favor of this technique and the expansion of its indication to intermediate-risk patients38–40 have favored a dramatic increase, from 43 implants per million population in 2016 to 61 in 2017. These figures place the rate per million population above the recently published European average,41 although still at a distance from countries such as France, Germany, and Switzerland. Another procedure showing significant growth is percutaneous mitral valve repair, mostly in patients with functional mitral valve regurgitation and high surgical risk, in line with the good clinical results observed for this indication in terms of improved functional class and cardiac remodeling.42 Left appendage closure, as indicated for patients with high risk of bleeding and contraindication to anticoagulation, also grew significantly, from 492 implantations in 2016 to 582 in 2017. In terms of structural heart disease outcomes, a significantly lower number of complications and more successful procedures have been reported this year across the board.

Finally, regarding the treatment of congenital heart diseases in adults, there was a higher number of permeable foramen ovale closures. Undoubtedly, the indication for this technique has expanded after the recent publication of several studies showing its efficacy vs medical treatment in the reduction of recurrent stroke in patients with a history of cryptogenic stroke.43

CONCLUSIONSThe activity collected in 2017 shows a slow but steady increase in the number of diagnostic and therapeutic coronary procedures, as well as a significant qualitative leap in intracoronary diagnostic techniques, particularly the use of the pressure guidewire. The dominance of the radial approach and the progressive increase in primary angioplasty as a treatment for AMI are clear indicators of the quality of Spanish interventional activity. There has been a marked increase in the number of procedures for structural heart disease, both in transcatheter aortic valve implantation and in atrial closure and percutaneous mitral valve repair, which moves Spain closer to European standards.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

The Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology would like to thank the directors of the cardiac catheterization laboratories throughout Spain, all of those responsible for data collection, and all of our peers whose work and enthusiasm ensure fair and first-rate patient care.

| Community | Public hospitals | Private hospitals |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Complejo Hospitalario Torrecárdenas Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real Hospital de Jerez de la Frontera Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga Carlos Haya Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria Hospital Costa del Sol Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío Hospital Universitario de Valme Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | Hospital Vithas Virgen del Mar Hospital de Estepona |

| Aragon | Hospital Universitario Lozano Blesa Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias Hospital de Cabueñes | Centro Médico de Asturias |

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | |

| Castile and León | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca Hospital Universitario de Burgos Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid Hospital de León | Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande |

| Castile-La Mancha | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo | |

| Catalonia | Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrassa Hospital del Mar Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau Hospital Universitari Clínic i Provincial Hospital Universitario Dr. Josep Trueta Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII | Hospital General de Cataluña Hospital Quirónsalud Barcelona Hospital Universitario Quirón Dexeus Centro Cardiovascular San Jordi |

| Valencian Community | Hospital Elche-Crevillente/Torrevieja Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante Hospital General Universitario de Alicante Hospital General Universitario de Castellón Hospital General Universitario de Valencia Hospital Universitario de la Ribera Hospital Universitario La Fe Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia Hospital de Manises Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset | Hospital Clínica Benidorm Hospital IMED Levante Hospital IMED Elche Hospital Vithas Perpetuo Socorro Internacional |

| Extremadura | Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina Hospital de Mérida Hospital de Cáceres | |

| Galicia | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo-Álvaro Cunqueiro | Hospital San Rafael |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases | Hospital Juaneda Miramar Clínica Rotger Clínica Quirónsalud Palmaplanas |

| Canary Islands | Hospital Universitario Insular Hospital Universitario Dr. Negrín Complejo Nuestra Señora de Candelaria Hospital Universitario de Canarias | Hospiten Rambla Sur |

| Community of Madrid | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal Hospital de La Princesa Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre Fundación Jiménez Díaz Hospital General de Villalba Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Hospital Universitario de Torrejón Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón Hospital Clínico San Carlos Hospital Universitario La Paz Hospital Infantil La Paz | Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Zarzuela Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de América Hospital La Milagrosa Hospital Universitario Moncloa Hospital Montepríncipe |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital Univestiario Virgen de la Arrixaca Hospital Santa María del Rosell (Cartagena) | Hospital Quirónsalud Murcia Hospital Virgen de la Vega |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Hospital de Navarra | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra |

| Basque Country | Hospital Universitario Araba-Txagorritxu Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital de Cruces Hospital de Basurto Policlínica Gipuzkoa-Hospital Universitario Donostia | |

| La Rioja | Complejo de Salud San Millán-Hospital San Pedro |