The Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology presents its annual report on the data from the registry of the activity in 2015.

MethodsAll Spanish hospitals with catheterization laboratories were invited to voluntarily contribute their activity data. The information was collected online and analyzed mostly by an independent company.

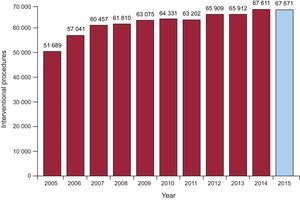

ResultsIn 2015, 106 centers participated in the national register; 73 of these centers are public. A total of 145 836 diagnostic studies were conducted, among which 128 669 were coronary angiograms. These figures are higher than in previous years. The Spanish average of total diagnoses per million population was 3127. The number of coronary interventional procedures was very similar (67 671), although there was a slight increase in the complexity of coronary interventions: 7% in multivessel treatment and 8% in unprotected left main trunk treatment. A total of 98 043 stents were implanted, of which 74 684 were drug-eluting stents. A total of 18 418 interventional procedures were performed in the acute myocardial infarction setting, of which 81.9% were primary angioplasties. The radial approach was used in 73.3% of the diagnostic procedures and in 76.1% of interventional ones. The number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations continued to increase (1586), as well as the number of left atrial appendage closures (331).

ConclusionsAn increase in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in acute myocardial infarction was reported in 2015. The use of the radial approach and drug-eluting stents also increased in therapeutic procedures. The progressive increase in structural procedures seen in previous years continued.

Keywords

As in every year since 1990,1–24 the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology has collected data on the activity of Spanish cardiac catheterization laboratories. Up to the present, data have been contributed on a voluntary basis and collected via an online database to facilitate participation. This year, the company in charge of the website has been changed and the database has been modified. One of the most important changes is the incorporation of variables on structural interventionism, which is a growing field, and variables on immediate clinical outcome. An independent company analyzed the data. The preliminary results were presented at the annual reunion of the working group on the 16 and 17 June in Leon (Spain).

An annual national registry is important in that it enables the analysis of overall improvements not only by year but also by autonomous community in the management of clinical processes and the implementation of healthcare networks, such as the infarction code program. Modifications to the database this year also allow the activity and procedural results to be compared with those of other countries in Europe.

In 2015, there was an increase in coronary interventions, as well as in structural heart disease and adult congenital disease interventions. This article presents the 25th report of interventional activity in public and private hospitals in Spain.

METHODSData were collected on diagnostic and interventional cardiac activity in the majority of Spanish hospitals. Data were provided on a voluntary basis without audit. Anomalous data or data that deviated from the trend observed in a hospital in recent years were referred back to the hospital for reassessment. Data were collected via a standard electronic questionnaire, which could be accessed, completed, and consulted on the website of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.25 The Tride company analyzed the data obtained. The working group steering committee compared the data to those of previous years. The results are published in this article, although a preliminary draft was presented as a slideshow at the working group's annual meeting.

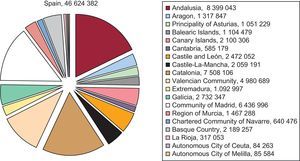

As in previous years, population-based calculations for Spain and each autonomous community were based on the size of the population estimated by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics up to January 1, 2016, as published on its website.26 The Spanish population was estimated to have increased to 46 624 382 inhabitants (Figure 1). As in recent years, the procedures per million population for the entire country were calculated using the total population.

Population of Spain on 1 January 2016. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.25

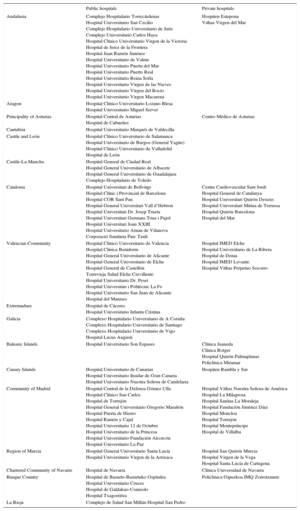

A total of 106 hospitals performing interventional procedures in adults participated in the present registry; most of these hospitals were public (n=73) (Appendix). There were 209 catheterization laboratories, of which 133 (63.6%) were exclusively dedicated to cardiac catheterization, 55 (26.4%) had shared activity, and 21 (10.0%) were hybrid laboratories.

The hospitals reported a total of 661 physicians performing interventional procedures in 2015 (425 of them were accredited) and 76 medical interns. There were 508 registered nurses and 94 radiology technicians.

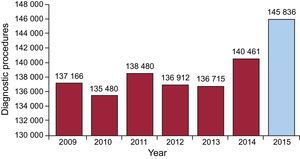

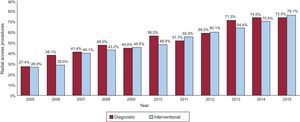

Diagnostic ProceduresIn 2015, 145 836 diagnostic studies were performed, of which 128 669 (88%) were coronary angiograms, representing a 3.8% and 2.5% increase compared to 2014. A total of 11 267 (8%) diagnostic studies were performed in patients with valvular heart disease. Figure 2 shows changes in the number of diagnostic studies since 2009. The number of procedures performed via the radial approach increased from 103 957 (71.3%) in 2014 to 107 226 (73.5%) in 2015.

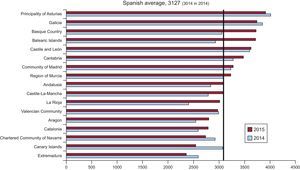

Regarding diagnostic studies by autonomous community, the national average of diagnostic studies per million population was 3127 (3014 in 2014), of which 2746 (2693 in 2014) were coronary angiograms. Figure 3 shows the number of diagnostic studies per million population by autonomous community. The number of myocardial biopsies increased from 1484 in 2014 to 1652 in 2015. Regarding diagnostic activity by hospital, 64 performed more than 1000 diagnostic studies (62 hospitals in 2014) and 17 performed more than 2000 (16 hospitals in 2014). The average number of diagnostic procedures per hospital was 1388 (1338 in 2014).

Diagnostic studies per million population, Spanish average, and total by autonomous community in 2014 and 2015. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.25

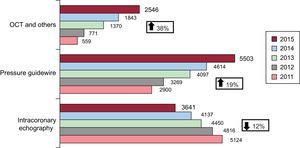

As in previous years, there was a continuing upward trend in the use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques, with an increase in the use of pressure guidewire (19%), a marked increase in optical coherence tomography (38%), and a decrease in the use of intracoronary ultrasound (12%) (Figure 4).

Percutaneous Coronary InterventionThe number of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) slightly increased from 67 611 in 2014 to 67 671 in 2015. However, there was an increase in the number of complex procedures, such as PCI in multivessel disease (18 278 in 2015 vs 17 059 in 2014) and PCI in unprotected left main coronary artery disease (2202 in 2015 vs 2028 in 2014). The figures for 2015 represent increases of 7% and 8%, respectively. In contrast, the number of chronic occlusions treated was 2838 (4.2% of all PCIs), which was similar to the previous year. A total of 8163 bifurcations were treated (12.1% of all PCIs). These figures account for the slight decrease in the number of ad hoc procedures: 69.5% in 2015 vs 71% in 2014. Figure 5 shows changes in the number of PCIs since 2005. The PCI to coronary angiography ratio was 0.52.

Similar to its use in diagnostic procedures, there was an increase in the use of the radial approach in PCI in 2015 (76.1% vs 70.3% in 2014). Figure 6 shows changes in the number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures using the radial approach since 2005.

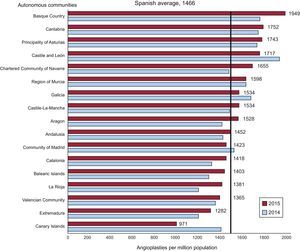

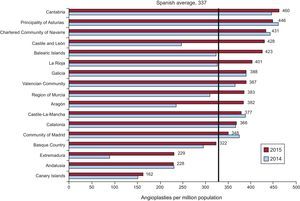

Adjuvant drug therapy, other than unfractionated heparin, was little used in PCI (12.6%). Abciximab was used in 7.6% of PCIs and eptifibatide and tirofiban were used in<1% of PCIs. Bivalirudin and fondaparinux were used in 2.4% and 2% of PCIs, respectively. The average number of PCIs per million in Spain was 1466 (1447 in 2014). Figure 7 shows the distribution of PCIs by autonomous community. In total, 8 autonomous communities were below the Spanish 2015 average (8 in 2015 vs 10 in 2014).

Primary angioplasties per million population, Spanish average, and total by autonomous community in 2014 and 2015. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.25

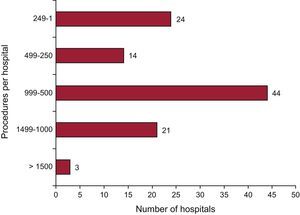

Figure 8 shows the distribution of PCI by hospital in 2015. In total, 24 hospitals performed more than 1000 PCI per year (2 hospitals more than in 2014), 44 performed between 500 and 1000, and 38 performed less than 500. Data on immediate clinical outcome variables in PCI were provided in 74% of cases (slightly more than in 2014: 71%). In total, 94.2% were reported as having been successfully performed without complications, 1% reported severe complications (infarction, need for urgent surgery, or death), and 0.38% reported intraprocedural death.

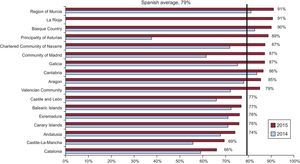

StentsThe number of stents implanted increased from 94 458 in 2014 to 98 043 in 2015. The stent to patient ratio was 1.44 (1.4 in 2014, 1.5 in 2013, and 1.6 in 2010). The use of drug-eluting stents (reported by 95.4% of hospitals) increased by 16.6% from 67.8% (64 057 units) in 2014 to 79% (74 684 units) in 2015. The use of drug-eluting stents increased in all autonomous communities (Figure 9). The prevalence of direct stent implantation was 38.4%. The number of biodegradable device procedures was 2685 (3.9% of all stents), which was slightly higher than the previous year (2424 reported devices; 2.5%). Bifurcation stents were used in 294 procedures (0.43%), self-expanding stents in 164 (0.24%), and polymer-free stents in 3395 (5.0%).

Other Devices and Procedures Used in Percutaneous Coronary InterventionThe use of rotational atherectomy was similar to previous years with 1262 cases (1251 in 2014 and 1254 in 2013). The use of cutting balloons decreased slightly to 2285 in 2015 (2335 in 2014); nevertheless, the use of other types of special balloons slightly increased to 1174 vs 980 in 2014. On the other hand, the use of drug-coated balloons levelled out with 2357 cases. The use of thrombectomy catheters stabilized (8813 in 2015 vs 8981 in 2014), although that of distal embolic protection devices decreased by more than 50% (132 in 2015 vs 305 in 2014).

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial InfarctionThe number of PCIs in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) increased by 3.3% after a decrease in the previous year (18 418 in 2015 vs 17 825 in 2014 and 18 337 in 2013). Most of these procedures were primary angioplasties (15 089 [81.9%] vs 14 600 in 2014). Following the trend in previous years, there was a decrease in the number of nonprimary PCIs in AMI. Rescue PCI was used in 954 cases (1129 in 2014). Immediate PCI after pharmacoinvasive reperfusion was performed in 258 cases (343 in 2014), and deferred or planned PCI after thrombolysis was performed in 1330 cases (1725 in 2014). These figures are probably the result of some autonomous communities implementing the infarction code program. Primary PCIs represented 27.1% of all angioplasties and 81.9% of PCIs in AMI.

The average number of primary PCIs per million population in Spain was 337 (131 in 2014 and 299 in 2013). Regarding the rate of primary PCIs by autonomous community (Figure 10), there was a striking increase in communities such as Castile and León, the Balearic Islands, La Rioja, the Region of Murcia, Aragon, and Extremadura. Similarly, the number of communities that did not reach the national average fell from 6 communities in 2014 to 4 in 2015. However, some hospitals may not have included their data and thus these figures should be taken with caution because of possible bias. Regarding the number of procedures per hospital, 42 performed more than 200 per year (2 hospitals less than in 2014), whereas 23 performed less than 50 (3 less than in 2014).

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Structural Heart DiseaseThe number of mitral valvuloplasties slightly decreased to 235 (256 in 2014 and 240 in 2013). The technique was successful in 195 cases (83%). However, there was failure without complications in 15 cases (6.4%) and acute complications in 10 (4.2%), which comprised 4 cases of cardiac tamponade, 5 cases of severe mitral regurgitation, and 1 case of severe mitral regurgitaiton and stroke. No deaths were reported. In contrast, there was a continued increase in the number of isolated aortic valvuloplasties (i.e. unrelated to transcatheter aortic valve implantation). In 2015, there were 240 procedures (229 in 2014 and 201 in 2013). Procedures were successful in 206 patients (85.8%). There were 14 cases (5.8%) with complications, which comprised 4 cases of aortic regurgitation and 11 deaths.

There was a significant increase in the number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations compared to the previous 2 years: 1586 in 2015, 1324 in 2014, and 1041 in 2013. Most of these procedures were performed in patients with surgical contraindications or high surgical risk (73.2%). In most cases, the transfemoral approach was used (1353; 85%) followed by the transapical approach (77; 4.8%). Data on the results during hospitalization are only available in 74% of cases. Procedural success without any type of major complication was achieved in 74% of cases, whereas there were major complications (AMI, stroke, or need for vascular surgery) in 7 cases (0.4%). A permanent pacemaker was needed in 173 cases (10.9%). Hospital mortality rose to 3.2%. The type of prosthesis most frequently used was the expandable balloon (Edwards; 829 units [54%]), closely followed by the self-expanding valve (CoreValve; 653 units [41.2%]). A total of 50 mechanically expanded prosthesis (Lotus) were implanted. Transcatheter mitral valve implantation was performed in 5 cases and was successful in 3 cases without complications. No cases were reported of transcatheter tricuspid valve implantation.

Regarding the treatment of paravalvular leaks, there was a very significant decrease in the treatment of aortic leaks (50 in 2015 vs 127 in 2014) and, to a lesser extent, in the treatment of mitral leaks (112 in 2015 vs 168 in 2014). In general, procedural success was achieved in 134 cases (82.7%) and complications were observed in 6 cases.

There were 334 atrial appendage closures, of which 269 were performed with disk-and-lobe devices (Amplatzer/Amulet) and 51 with a one-piece devices (Watchman); in the remaining cases the type of device was not reported. Major complications were observed in 7 cases.

In 2015, 141 implantation procedures were performed with the MitraClip; in most cases 1 or 2 clips (n=136 [96%]) were used. The most common cause of mitral regurgitation was functional (n=109 [77%]) followed by organic (23 cases [23%]); the remainder were due to mixed causes. Implantation was successful in 136 cases (96.4%) and 4 deaths were recorded.

There were 79 septal ablation procedures, 75 percutaneous stem cell administration procedures, 46 endovascular aortic repair procedures, and 50 renal denervation procedures.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Adult Congenital Heart DiseaseThe number of atrial septal defect closures rose from 292 in 2014 to 313 in 2015. There was 1 case of tamponade and 3 cases of device embolization, without any death being reported. Similarly, there was an increase in patent foramen ovale closures (217 in 2015 vs 176 in 2014) with no complications reported, and 1 device implantation failure without complications. There were 25 patent ductus arteriosus closures (without complications) and 15 ventricular septal defect closures (3 cases with complications). A total of 33 pulmonary valvuloplasty procedures were performed with an 81% success rate. One pulmonary valve was implanted in adults in 18 cases, and in almost every case a Melody valve was used (success rate 91.6%). Percutaneous stent implantation for aortic coarctation in adults was performed in 59 cases. Gerbode defect closure was performed and in 3 cases stents were implanted in the pulmonary branches and in 1 case a stent was implanted in the renal artery.

DISCUSSIONThe registry for 2015 reported an increase in the number of diagnostic studies and myocardial biopsies. There was greater use of the radial access approach than in 2014, both in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The pressure guidewire remained the most-used intracoronary diagnostic technique and, following recent trends, its use increased each year. However, the use of intracoronary ultrasound, despite being the second most-used technique, continued to decrease probably because of the increasingly frequent use of optical coherence tomography.

Although the total number of therapeutic procedures remained similar to that of 2014, there was an increase in the percentage of PCIs in multivessel disease and unprotected left main trunk disease. Consistent with the foregoing, there was an increase in the number of stents used and a notable increase in the percentage of drug-eluting stents used. The use of adjuvant techniques and devices in interventionism, such as rotablation and thrombus extraction, remained very similar to that of recent years. Regarding structural interventionism, there was an increased number of transcatheter aortic ventricular implantations and atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale closures. There was a very significant increase in the number of atrial appendage closures.

The annual increase in the use of the radial approach was consistent with global trends, which developed after studies showed that this approach reduces the risk of complications associated with site access and the risk of bleeding. Compared with femoral access, decreases in mortality have also been observed when the technique is used in ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome.27,28 Although the use of radial access has been associated with a slight increase in exposure to radiation,29 such exposure decreases with the experience of the operator30 and is compensated for by clear clinical benefit. However, the effect of this approach on upper extremity function remains to be elucidated.31 This issue is the subject of a prospective study whose preliminary results were recently presented at EuroPCR 2016.

A very positive fact that reflects the progressive implantation of the infarction code program in the autonomous communities is the steady increase in the use of primary angioplasty in Spain. We are far beyond the figure published in 2010 in a European report on primary PCI, in which Spain, with 251 primary PCIs per million population, was trailing the rest of Europe. Just 5 years later the percentage had increased to 34%.32

In terms of structural interventionism, we highlight the striking increase in the number of atrial appendage closures reported (334 in 2015 vs 51 in 2014). This increase reflects the upsurge in this technique, especially in patients at a high risk of bleeding or with contraindications for anticoagulation therapy.33,34. The transcatheter aortic ventricular implantation rate has continued to increase each year, although it still remains very far from that of other European countries. Petronio et al.35 recently published a survey on the state of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Europe, in which 301 centers participated. The survey showed that only 4% of Spanish hospitals have performed more than 500 procedures since the beginning of the program, in comparison, for example, with Germany (54%), France (14%), or Italy (3%). It is to be hoped that there will be a strong increase in the number of these procedures in the coming years, given the increase in indications for this technique stemming from the recent publication of good results in intermediate-risk patients.36

CONCLUSIONSThe Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry data for 2015 show a continuous increase in the use of the radial approach, primary angioplasty, and coated stents. Thus, there has been a decrease in differences between autonomous communities, which have all increased the number of PCIs and primary PCIs and the use of covered stents. Structural heart disease procedures have steadily increased each year, with an especially striking increase in the number of atrial appendage closures reported this year.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology would like to thank the directors of cardiac catheterization laboratories throughout Spain, all those responsible for data collection, and all other collaborators for their work.

| Public hospitals | Private hospitals | |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Complejo Hospitalario Torrecárdenas Hospital Universitario San Cecilio Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Jaén Complejo Universitario Carlos Haya Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria Hospital de Jerez de la Frontera Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez Hospital Universitario de Valme Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar Hospital Universitario Puerto Real Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | Hospiten Estepona Vithas Virgen del Mar |

| Aragon | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Central de Asturias Hospital de Cabueñes | Centro Médico de Asturias |

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | |

| Castile and León | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca Hospital Universitario de Burgos (General Yagüe) Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid Hospital de León | |

| Castile-La-Mancha | Hospital General de Ciudad Real Hospital General Universitario de Albacete Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo | |

| Catalonia | Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona Hospital COR Sant Pau Hospital General Universitari Vall d’Hebron Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí | Centre Cardiovascular Sant Jordi Hospital General de Catalunya Hospital Universitari Quirón Dexeus Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa Hospital Quirón Barcelona Hospital del Mar |

| Valencian Community | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia Hospital Clínica Benidorm Hospital General Universitario de Alicante Hospital General Universitario de Elche Hospital General de Castellón Torrevieja Salud Elche Crevillente Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante Hospital del Manises | Hospital IMED Elche Hospital Universitario de La Ribera Hospital de Denia Hospital IMED Levante Hospital Vithas Perpetuo Socorro |

| Extremadura | Hospital de Cáceres Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina | |

| Galicia | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo Hospital Lucus Augusti | |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases | Clínica Juaneda Clínica Rotger Hospital Quirón Palmaplanas Policlínica Miramar |

| Canary Islands | Hospital Universitario de Canarias Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | Hospiten Rambla y Sur |

| Community of Madrid | Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla Hospital Clínico San Carlos Hospital de Torrejón Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón Hospital Puerta de Hierro Hospital Ramón y Cajal Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre Hospital Universitario de la Princesa Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón Hospital Universitario La Paz | Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de América Hospital La Milagrosa Hospital Sanitas La Moraleja Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz Hospital Moncloa Hospital Torrejón Hospital Montepríncipe Hospital de Villalba |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca | Hospital San Quirón Murcia Hospital Virgen de la Vega Hospital Santa Lucía de Cartagena |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Hospital de Navarra | Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Basque Country | Hospital de Basurto-Basurtuko Ospitalea Hospital Universitario Cruces Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital Txagorritxu | Policlínica Gipuzkoa IMQ Zorrotzaurre |

| La Rioja | Complejo de Salud San Millán-Hospital San Pedro |