This report presents the findings of the 2018 Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry.

MethodsData collection was retrospective. A standardized questionnaire was completed by each of the participating centers.

ResultsData sent by 100 centers were analyzed, with a total number of 16566 ablation procedures performed (the highest historically reported in this registry) for a mean of 165.5±127.9 and a median of 119 procedures per center. The ablation targets most frequently treated were atrial fibrillation (n=4234; 25.6%), atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (n=3525; 21.3%) and cavotricuspid isthmus (n=3425; 20.7%). A new peak was observed in the ablation of atrial fibrillation, increasing the distance from the other substrates. The overall success rate was 91%. The rate of major complications was 2.2%, and the mortality rate was 0.04%. A total of 2.1% of the ablations were performed in pediatric patients.

ConclusionsThe Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry enrolls systematically and continuously enrolls the ablation procedures performed in Spain, showing a progressive increasing in the number of ablations over the years, with a high success rate and low percentage of complications.

Keywords

The purpose of the present article is to report the findings of the Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry, the Official Report of the Working Group on Electrophysiology and Arrhythmias of the Spanish Society of Cardiology for 2018, which marks the 18th year of uninterrupted activity by this group.1–17 The registry is a voluntary nationwide record, published annually, that includes data from arrhythmia units operating in Spain, making it one of the few large-scale, observational registries focusing on catheter ablation.

The main objectives of the registry are to analyze and describe developments in the interventional treatment of cardiac arrhythmias in Spain and to provide reliable information on the type of activity performed and the facilities available in Spanish arrhythmia units.

METHODSData were retrospectively collected using a standardized data collection form sent to all interventional electrophysiology laboratories in January 2019; the form was also available on the website of the Working Group on Electrophysiology and Arrhythmias.18 All of the compiled data remained anonymous, even to the registry coordinators, with the secretariat of the Spanish Society of Cardiology removing any identifying information from the data.

The information collected concerned the technical and human resources available in the arrhythmias units, the procedures performed, and their results and complications.

We analyzed the same 10 arrhythmias and arrhythmogenic substrates examined in previous registries: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), accessory pathways, atrioventricular node ablation, focal atrial tachycardia (FAT), cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI), macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia (MAT), atrial fibrillation (AF), idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (IVT), ventricular tachycardia associated with myocardial infarction (VT-AMI), and ventricular tachycardia not associated with myocardial infarction (VT-NAMI). The following variables common to these 10 conditions were analyzed: number of patients and procedures, success rate, type of ablation catheter used, and procedure-related complications, including periprocedural death. The numbers of procedures performed with a navigation system and of those performed without fluoroscopy were also recorded for all substrates, as well as the number of procedures performed in pediatric patients (defined as those younger than 15 years of age). In addition, a number of ablation target-specific variables were analyzed: location and type of accessory pathway conduction, location and mechanism of atrial tachycardias, type of AF ablation and approach, and ventricular tachycardia substrate.

As in previous years, the success rate refers only to the immediate postprocedural data (acute success rate). As for complications, only those occurring during the hospital stay after the procedure were reported.

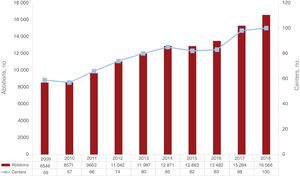

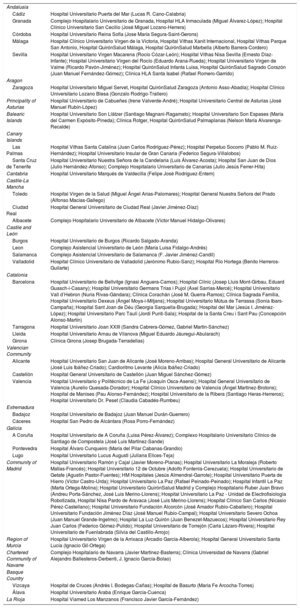

RESULTSIn total, 100 centers participated in the 2018 registry (appendix 1 and appendix 2), representing a continuous increase (2% more than in 2017). Similarly, the highest number of ablation procedures of the registry, a total of 16 566, was reported in 2018, representing a 7.7% increase vs 2017 (figure 1).

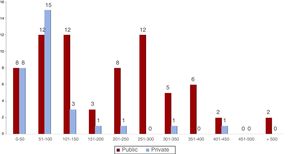

Of all participating centers, 70 (70%) were public and 30 (30%) were private. These proportions were very similar to those of the previous registry (figure 2).

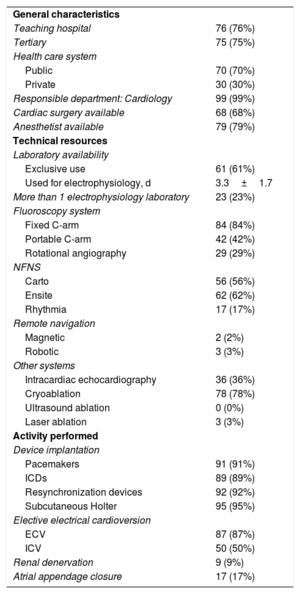

The technical and human resources available in the participating laboratories, as well as the activity performed, are presented in table 1 and table 2.

General characteristics, technical resources, and activity (in addition to catheter ablation) of the 100 electrophysiology laboratories in the 2018 registry

| General characteristics | |

| Teaching hospital | 76 (76%) |

| Tertiary | 75 (75%) |

| Health care system | |

| Public | 70 (70%) |

| Private | 30 (30%) |

| Responsible department: Cardiology | 99 (99%) |

| Cardiac surgery available | 68 (68%) |

| Anesthetist available | 79 (79%) |

| Technical resources | |

| Laboratory availability | |

| Exclusive use | 61 (61%) |

| Used for electrophysiology, d | 3.3±1.7 |

| More than 1 electrophysiology laboratory | 23 (23%) |

| Fluoroscopy system | |

| Fixed C-arm | 84 (84%) |

| Portable C-arm | 42 (42%) |

| Rotational angiography | 29 (29%) |

| NFNS | |

| Carto | 56 (56%) |

| Ensite | 62 (62%) |

| Rhythmia | 17 (17%) |

| Remote navigation | |

| Magnetic | 2 (2%) |

| Robotic | 3 (3%) |

| Other systems | |

| Intracardiac echocardiography | 36 (36%) |

| Cryoablation | 78 (78%) |

| Ultrasound ablation | 0 (0%) |

| Laser ablation | 3 (3%) |

| Activity performed | |

| Device implantation | |

| Pacemakers | 91 (91%) |

| ICDs | 89 (89%) |

| Resynchronization devices | 92 (92%) |

| Subcutaneous Holter | 95 (95%) |

| Elective electrical cardioversion | |

| ECV | 87 (87%) |

| ICV | 50 (50%) |

| Renal denervation | 9 (9%) |

| Atrial appendage closure | 17 (17%) |

ECV, external cardioversion; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ICV, internal cardioversion; NFNS, nonfluoroscopic navigation system.

Values represent No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Changes in the human resources in the electrophysiology laboratories of public hospitals participating in the registry since 2009

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff physicians | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.5 |

| Full-time physicians | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Residents/y | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| RNs | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| RTs | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

RN, registered nurse; RT, radiologic technologist.

In total, 61 centers (61%) were equipped with at least 1 dedicated cardiac electrophysiology laboratory. Most centers had 1 room (77%), 22 had 2 (22%), and 1 had 3 (1%). On average, the laboratory was available on 3.3 ± 1.7 (median, 4) days a week.

In addition to electrophysiological procedures, cardiac devices were implanted in 99% of centers: subcutaneous Holter monitors in 95%, resynchronization devices in 92%, pacemakers in 91%, and defibrillators in 89%.

At least 1 fixed C-arm fluoroscopy system was available in 71 centers (71%) and at least 1 portable C-arm fluoroscopy system was available in 40 (40%). Most centers (86%) had at least 1 nonfluoroscopic navigation system, 25% of the centers had 2, and 12% had 3. In addition, 29% of the centers had an X-ray system with integrated fluoroscopy (rotational angiography).

Intracardiac echocardiography was available in 36 centers (36%). The most common ablation technique after radiofrequency was cryoablation, whose use increased this year (78.0% vs 72.4% in 2017). Other energy sources, such as laser, were rare.

Personnel numbers continue to rise (table 2); the electrophysiology laboratories had an average of 3.5 staff physicians, although the full-time average was 2.3. There was at least 1 full-time physician in 79% of centers and 2 or more in 64%. The average number of nurses per center was maintained at 2.7 registered nurses; 81% of laboratories had 2 or more (range, 1-6). Furthermore, 36% of the laboratories had fellows, typically 1 (range, 1-10).

Overall ResultsThe number of centers participating in the registry was slightly higher this year than in the previous year (100 vs 98); changes in participation over time are shown in figure 1. In addition, the number of ablations performed (16 566) was the highest reported to the registry and represents a 7.7% increase vs 2017. The mean number of procedures per center was 165.5±127.9 (higher than in 2017 [156±126]), and the median was 119 (range, 4-579).

Seventeen centers (15 public) reported more than 300 ablations and 5 centers (4 public) reported more than 400 (figure 2).

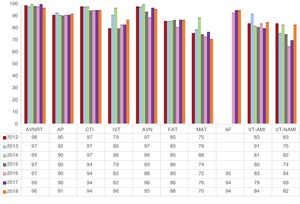

The overall success rate was 91%, similar to that of previous years. The success rates of all ablation procedures since 2012 are shown in figure 3, although the rates for AF are only from 2016, when the new data collection form was introduced.

Changes in catheter ablation success rates since 2012 by the arrhythmia or arrhythmogenic substrate treated. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia; VT-AMI, ventricular tachycardia associated with acute myocardial infarction; VT-NAMI, ventricular tachycardia not associated with acute myocardial infarction.

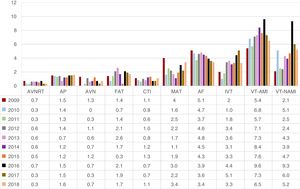

The number of complications reported for all ablation procedures was 332, which represents 2% and is slightly lower than those of the previous 2 years (2.6% and 2.3%, respectively). The most common complications were vascular (34% of complications), followed by pericardial effusion/cardiac tamponade (25%). There were 20 iatrogenic atrioventricular blocks (0.1% of total ablations and 6% of all complications). The changes in intracoronary diagnostic techniques in the last 10 years according to ablation target are shown in figure 4.

Changes in major complications related to catheter ablation since 2009 by the arrhythmia or arrhythmogenic substrate treated. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia; VT-AMI, ventricular tachycardia associated with acute myocardial infarction; VT-NAMI, ventricular tachycardia not associated with acute myocardial infarction.

Six periprocedural deaths (0.04%) were recorded, 4 less than in the previous year. Three of the deaths occurred during ventricular tachycardia ablation. One death occurred in the context of a complication reported as acute myocardial infarction during AF ablation. Another death was described as refractory heart failure 24hours after atrioventricular ablation. In the last reported death, the cause was not described, although it occurred during accessory pathway ablation.

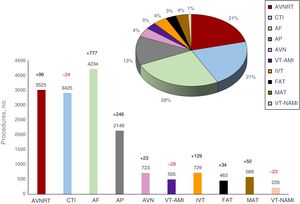

Regarding the frequencies of the different ablation targets and the changes over time, AF was consolidated as the most frequently treated substrate (25.6%), followed by nodular re-entry tachycardia (21.3%) and CTI (20.7%) (figure 5).

Relative frequency of the different ablation targets treated by catheter ablation in Spain in 2018 (16 566 procedures). The change in the number of cases vs the previous registry is also shown for each ablation target. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia/atypical atrial flutter; VT-AMI, ventricular tachycardia associated with acute myocardial infarction; VT-NAMI, ventricular tachycardia not associated with acute myocardial infarction.

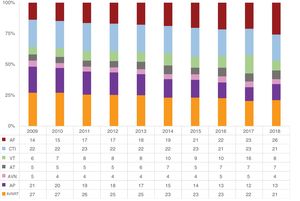

Compared with 2017, the number of ablations of all substrates increased, except those of CTI, VT-AMI, and VT-NAMI (figure 5). The changes in the relative frequencies of the different ablation targets since 2009 are shown in figure 6. There was a notable continuous increase in AF ablation during the last 10 years vs the other substrates. This year also showed a noteworthy decrease in ventricular tachycardia ablation.

Changes in the relative frequency of different ablation targets treated since 2009. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AT, atrial tachycardia (focal and atypical flutter); AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

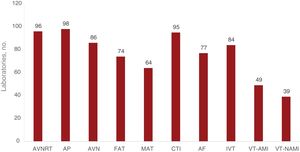

Information on the number of laboratories treating each of the different ablation targets is shown in figure 7. The accessory pathways were the most frequently treated ablation target in the participating centers (98%), followed by AVNRT (96%) and CTI (95%). The number of centers performing AF ablation is stable (77%; 74% in the 2017 registry and 78% in 2016).

Number of electrophysiology laboratories participating in the registry that treat each of the different ablation targets. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia/atypical atrial flutter; VT-AMI, ventricular tachycardia associated with acute myocardial infarction; VT-NAMI, ventricular tachycardia not associated with acute myocardial infarction.

The following sections summarize the data analysis for the different subgroups.

Atrioventricular Nodal Re-entrant TachycardiaIn 2018, this target was once again the second most treated substrate. A total of 3525 AVNRT ablation procedures were performed (21% of the total) in 96 hospitals. There were 96 more procedures than in the previous year, which, in conjunction with a slight reduction in CTI ablation procedures, explains its elevation to second place.

The mean number of procedures was 31.3±12 (range, 1-145), with a success rate of 96%; 69% of centers reported a 100% success rate.

Eleven severe complications were reported (0.3%): 3 cases of atrioventricular block requiring a pacemaker, 6 vascular complications, 1 heart failure event, and 1 pulmonary thromboembolism.

The 4-mm radiofrequency ablation catheter tip is still the most frequently used catheter (96% of procedures). Although the use of other catheters and energy sources was low, the use of cryoablation increased this year, to second place (2.2%), followed by 8-mm catheters (1.1%); irrigated catheters occupied the final position with limited use (0.7%).

The use of navigation systems remained stable vs last year (10.9%), and most of these procedures were performed without fluoroscopy (10% of the total).

Cavotricuspid IsthmusCTI ablation, with 3425 procedures (20.7%), was the third most commonly targeted substrate after AF and AVNRT. It was performed in 95 centers, with a mean of 34.2±27.5 (0-119) procedures per center. It was successfully completed in 94% of cases (60 centers [63%] reported a 100% success rate).

There were 38 major nonfatal complications (1.1%), including 18 vascular complications (3.4%), 9 atrioventricular blocks (0.3%), 6 embolisms (0.2%), 2 pericardial effusions, 2 myocardial infarctions, and 1 heart failure event.

Conventional irrigated tip catheters remain the most frequently used, with 1792 procedures (54.4%), although irrigated catheters with contact forcesensing technology doubled since 2017 (247; 7.5%). The use of 8-mm catheters continues to fall (952; 28.9%). Navigation system use remained relatively stable, with 1013 procedures (29.6%), as did zero-fluoroscopy interventions, with 495 (14.4%).

Accessory PathwaysAccessory pathways remain the fourth most targeted substrate. The upward trend that was registered in 2017 continued, with a slight increase in the absolute number of procedures. Overall, 2148 procedures were performed in 98 centers, making it the substrate treated by the highest number of centers (7 more than in the previous year). A mean of 35.4±53.7 (1-90) procedures was performed. A success rate of 91% was obtained, with 30 centers reporting 100% success.

Bidirectional conduction remained the most frequent direction (40.8%), although the percentage of concealed pathways was very similar in 2018 (39.6%). Exclusively antegrade conduction pathways were the most infrequent (19.6%). Regarding their locations, left-sided accessory pathways continued to predominate (51.2%), followed by inferoseptal (27.1%), right ventricular free wall (11.9%), and para-Hisian (9.8%) pathways.

Navigation systems were used in 21.5% of procedures and 4.4% of the total was performed without fluoroscopy.

The retroaortic approach was still preferred (69%) for the ablation of left-sided pathways.

Procedural success rates by location were as follows: left ventricular free wall, 96%; right ventricular free wall, 88.6%; inferoseptal, 86.5%; and para-Hisian/anteroseptal, 74.1%.

Most ablations (61%) were performed with 4-mm ablation catheters. The use of irrigated catheters continued to increase (32.7%), although only 13% had contact forcesensing technology. Cryoablation was used in 4.6%, whereas the use of 8-mm catheters was limited (1.7%).

There were 35 major complications (1.6%): 16 vascular, 5 atrioventricular blocks (2 permanent), 4 acute myocardial infarctions, 3 pericardial effusions, 1 heart failure event, 1 mitral regurgitation, 1 traumatic lesion of the femoral nerve, and 3 embolic phenomena (1 systemic, 1 air embolism in the right coronary artery, and 1 deep venous thrombosis). In addition, 1 patient died of unspecified causes.

Atrioventricular Node AblationThe number of these procedures remained stable, with 686 ablations performed in 86 centers. The success rate was 95%. Only 4 nonfatal complications were reported (0.7%), 1 vascular and 3 due to the onset of heart failure. One of the latter patients died 48hours after the ablation. Based on the available data, most of the procedures were performed with conventional 4-mm catheters (456; 66.5%). The distribution of the remainder was as follows: 160 conventional irrigated catheters (23.3%), 53 8-mm catheters (7.7%), and 11 irrigated contact forcesensing catheters (1.6%).

Focal Atrial TachycardiaIn total, 463 procedures (3%) were performed in 74 centers, with a success rate of 86%, as in 2017. This ablation target was located in the right atrium in 325 cases (with a 90.1% success rate) and in the left atrium in 138 (an 83.3% success rate). There were 8 complications (1.7%): 3 pericardial effusions (0.6%), 2 atrioventricular blocks (0.4%), 2 vascular complications (0.4%), and 1 phrenic nerve palsy (0.2%).

The use of irrigated tip catheters increased to 297 procedures (64.1%); a high number of catheters (141) had contact forcesensing technology.

A navigation system was used in 218 procedures (47.1%); 37 of these (8.0% of the total) were entirely performed without fluoroscopy.

Macroreentrant Atrial TachycardiaDespite a slight increase in both the number of centers targeting this arrhythmia (6 more than in 2017, up to 64 hospitals) and the number of procedures (588 in 579 patients, an increase of almost 10% [mean, 5.9; range, 0-26]), MAT remained one of the least addressed ablation targets in Spain. Of the 365 cases with this etiology, most occurred after a previous AF ablation (156 cases, 42.7%), as well as 72 in congenital heart disease (19.7%), 55 after atriotomy (15.1%), and 82 others (22.5%).

This procedure had the lowest success rate of all procedures, just 70%. Despite this and the complexity of the substrate, a navigation system was used in only 69.2% of cases. Just 0.7% of the total was performed without fluoroscopy.

Irrigated tip catheters with contact forcesensing technology (58.3%) surpassed conventional irrigated tip catheters (37.2%); the other types are rarely used (0.4%).

There were 20 nonfatal complications (3.4%): 10 pericardial effusions, 5 femoral vascular complications, 2 embolisms, 1 atrioventricular block, 1 chordal rupture, and 1 phrenic paralysis.

Atrial FibrillationAlthough only 3 new centers began to perform this procedure in 2018, making a total of 77 centers (75.5%), AF treatment overtook that of the other targets by some distance. It was thus consolidated as the most frequently treated substrate, with 4234 procedures in 3907 patients (26% of all ablations), 777 more procedures than in 2017.

The mean number of procedures per center was 42.3 (range, 0-198), with an acute success rate of 94.1%. Already, 33 centers perform more than 50 procedures per year (42.9% of the total); of these, 14 performed more than 100 procedures (18.2%). According to the available data (3747 ablations), the distribution by type was as follows: 2430 paroxysmal AF procedures (64.8%), 1158 persistent AF procedures (30.9%), and 159 long-standing (> 1 year) persistent AF procedures (4.2%).

Electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins was again the most common procedure (93%), with a success rate of 96.9%. In addition, there were 186 reductions of the antral electrogram (successful in 100%), 45 complex fractionated electrogram ablations (successful in 88.9%), and 136 superior vena cava isolations (successful in 74.3%). Left atrial lines were placed in 186 procedures, successfully in 82.2%. Other targets were reported in 66 procedures, such as 20 magnetic resonance-guided scar ablations in 2 centers and 15 rotor ablations in 2 others. Also noted were ablation of the ganglion plexus and of the pulmonary and extrapulmonary foci and a left atrial posterior box isolation.

Although the most commonly used technique for AF ablation is still point-by-point radiofrequency ablation, with 2323 procedures (55.7%), cryoablation continued to gain ground, reaching 1818 procedures (43.6%), 8% more than in 2017. There was limited use of other techniques such as the Multielectrode Pulmonary Vein Ablation Catheter (PVAC, Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, USA) (0.9%) and laser ablation (0.4%).

Irrigated catheters with contact forcesensing technology are more and more common and were used in 76.7% of point-by-point ablations in 2018.

The use of steerable sheaths was maintained this year (1025 cases), and they were deployed in 24.2% of all procedures in 33 centers. Intracardiac echocardiography is still rarely used, being applied in just 331 procedures (7.8%) and in only 14 centers.

Three-dimensional navigation was used for this ablation target in 2416 cases, exceeding the 2323 cases reported for point-by-point. This means that it was used in almost 100 cases of cryoablation/ablation with the multielectrode pulmonary vein ablation catheter (PVAC).

Several centers reported the use of “minimal fluoroscopy” and 3 procedures were even completely performed without fluoroscopy.

A total of 145 complications were recorded (3.4%), another slight decrease vs previous years: 3.9% in 2016 and 3.6% in 2017. Of these, 1 was fatal and was associated with ST-segment elevation of unspecified site. The distribution of the remainder was as follows: 49 vascular complications (1.2%), 33 pericardial effusions (0.8%), 27 phrenic nerve palsies (0.6%), 6 embolisms (0.1%), 5 infarctions (0.1%), 4 severe hypotensive events requiring catecholamines (0.1%), and 3 perforations (1 requiring surgery). No atrioesophageal fistulae were reported, although 1 center detected 12 esophageal erosions. Also reported were 1 hemoptysis and 1 aortic puncture.

Idiopathic Ventricular TachycardiaIn total, 729 procedures (4%) were performed in 688 patients in 84 centers (mean, 9.0±4.9 [0-30]). This ablation target experienced the greatest increase in the number of laboratories addressing it (12 more than in 2017).

Overall success was achieved in 85.8%. The following were reported: 354 tachycardias of the right ventricular outflow tract and 119 of the left ventricular outflow tract, 66 aortic root tachycardias, 40 fascicular tachycardias, 25 epicardial tachycardias, 1 pulmonary artery tachycardia, and 71 tachycardias distributed in different locations, including 15 in the papillary muscles, 5 in the summit of the left ventricle, and 4 para-Hisian. The most successfully ablated tachycardias were those of the right ventricular outflow tract and the pulmonary artery (95% and 100%, respectively). Success rates were higher for the aortic root and left ventricular outflow tract than for fascicular tachycardias (86.0%, 83.0%, and 82.5%, respectively). The most complex substrates remain those with an epicardial/coronary sinus location (68%).

Irrigated catheters were used in 85% of the reported cases (with contact forcesensing technology in 47%). A navigation system was used in 73.5% of cases and 7.7% of the procedures were fluoroscopy free.

There were 24 complications (3.3%): 19 effusions/tamponades, 2 vascular complications, 1 pericarditis, 1 atrioventricular block, and 1 patient who experienced left branch block that led to left ventricular dysfunction. One death was reported, but the cause was not stated.

Ventricular Tachycardia Associated With Myocardial InfarctionThe total number of VT-AMI ablation procedures was stable, with 505 procedures (3%) in 442 patients (mean, 6.5 [0-24]).

The type of ablation performed was reported for 84% of the procedures: 77 with a “standard” approach and 349 with a substrate approach. The overall success rate was 84.1% (the highest rate reported in the last 5 years).

An exclusively endocardial approach remains the most frequent (85.7%), although the number of combined approaches continues to increase, in line with the trend found in previous years (7.6% in 2016, 8.9% in 2017, and 11.2% this year). In contrast, use of the exclusively epicardial approach continued to be marginal, although it was slightly higher than the rate reported in 2017 (2.5% vs 1.2% in 2017). As for the endocardial approach, a balance between retroaortic (53%) and transseptal (47%) approaches was becoming established.

For this substrate, the application of all of the available technological support was evident, with a predominant use of navigation systems (84%). Although no procedure was performed without fluoroscopy, there was an apparent increase in the deployment of steerable sheaths (reaching 40% of cases) and the predominant use of irrigated tip catheters (93.2%), mainly with contact forcesensing technology (70%).

There were 33 complications (6.5%): 11 vascular complications (2.1%), 11 pericardial effusions (2.1%), 7 heart failure events (1.3%), 1 aortic puncture during the transseptal approach, without consequences, and 1 cardiac arrest requiring resuscitation. In addition, 2 deaths (0.4%) were reported: the first due to electromechanical dissociation after the end of the procedure; the other due to cardiac tamponade and refractory ventricular fibrillation.

Ventricular Tachycardia Not Associated With Myocardial InfarctionA total of 226 VT-NAMI ablation procedures (1.4%) were performed in 39 laboratories (mean, 6.3 [0-32]). This year, there was a fall in both the number of procedures and the number of laboratories involved (23 fewer procedures and 9 fewer centers) and it was the ablation target addressed by the fewest centers. The type of ventricular tachycardia substrate was specified in 213 cases: 114 in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (79% successful), 26 in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (96% successful), 10 in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (80% successful), 35 in congenital heart disease (83% successful), 16 bundle branch ventricular tachycardias (100% successful), and 15 miscellaneous cases (87% successful), including 3 after myocarditis, 1 in valvular heart disease, 1 in Chagas disease, and 1 in Brugada syndrome.

As for the approach used for these substrates, the number of exclusively epicardial approaches fell (11 procedures, which represents 4.9%), but there was a marked increase in the combined endocardial-epicardial approach (56 procedures, representing 24.8%). In addition, 81.4% of procedures were performed with navigation system support, although only 3 were fluoroscopy free.

The most commonly used catheter type continued to be the irrigated tip (98%), mainly with contact forcesensing technology (78%).

There were 12 complications (5.2%): 4 vascular complications (1.8%), 4 pericardial effusions/tamponades (1.8%), 1 heart failure event (0.4%), 1 atrioventricular block (0.4%), 1 peripheral embolism (0.4%), and 1 ventricular fibrillation (0.4%).

Zero-fluoroscopy AblationNonfluoroscopic navigation systems were used in 5944 procedures (35.9%). Such systems were most commonly used for point-by-point pulmonary vein isolation.

For 2017 and 2018, the registry collected data on zero-fluoroscopy procedures. In 2018, the number more than doubled that of 2017, reaching 1068 (6.4% of the total). As in the previous registry, the ablation target most commonly treated without fluoroscopy was the CTI (495 procedures, 14.4% of all CTI ablations). At the other extreme, VT-AMI was not ablated at all without fluoroscopy.

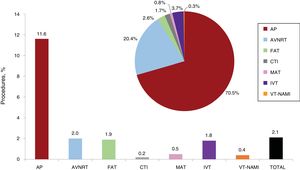

Ablations in Pediatric PatientsThe number of procedures in pediatric patients remained stable. In total, 353 ablation procedures (2.1% of the total) were performed in 46 centers (12 more than in 2017). In addition to the accessory pathways, which remained the most frequently treated substrate (representing 70.5% of all pediatric ablations and 11.6% of all accessory pathway ablations), 72 AVNRTs were ablated, as well as 9 FATs, 6 CTIs, 3 MATs, 13 IVTs, and 1 ventricular tachycardia associated with another (unspecified) heart disease (figure 8).

Pediatric ablation procedures. The bar chart shows the proportion of pediatric procedures for each ablation target and the total number of procedures in the registry while the pie chart shows the proportion of each substrate ablated with respect to the total number of pediatric procedures. AP, accessory pathway; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia; VT-NAMI, ventricular tachycardia not associated with acute myocardial infarction.

Catheter ablation therapy for cardiac arrhythmia has been continuously developing in Spain in recent years; 2018 marked a new record in terms of the number of procedures performed (16 566) and of centers submitting their data to the registry (100). The average number of procedures per center increased vs the previous year (165.5±127.9 vs 156.20±126 in 2017), but not the median, because the increase was due to centers with a high volume of procedures.

In addition, 2018 was the third year since the introduction of a single form and standardized retrospective data collection. As well as providing information on the portfolio of services and technical resources (eg, navigation systems, catheters) available in the laboratories, this form collects additional data on the most complex ablation targets (AF, MAT, and ventricular tachycardias), on whether fluoroscopy was used, and on ablations performed in pediatric patients; all of this information allows the preparation of a more complex report.

With respect to the proportional evolution of ablations in the different substrates, the tendency observed since the beginning of the registry was maintained. The numbers of AF ablations continued to progressively increase, and it was the most frequently ablated substrate for the second consecutive year, even showing a significant jump from the previous year.

Although point-by-point ablation remained predominant, cryoablation of pulmonary veins continued its rapid growth and accounted for 44% of the procedures. It is also interesting to observe the consolidation of new technologies, such as the increasing use of contact forcesensing catheters for many substrates.

However, the ablation of complex ventricular arrhythmias (VT-AMI and VT-NAMI) showed both an absolute and relative decrease in the number of procedures vs previous years.

Regarding success, complication, and mortality rates, the percentages remained stable vs previous registries. AF was the substrate with the highest number of complications, although the substrates with the highest percentages of complications were VT-AMI (6.5%) and VT-AMI (5.2%). Their high complication rates was related to the greater complexity of the procedures and the more severe situations of the patients.

Three deaths were also described for “simpler” ablation targets, such as accessory pathway, atrioventricular conduction, and IVT substrates, a reminder that all procedures are susceptible to complications.

Zero-fluoroscopy procedures continued to rise, reaching 6.4% of all cases reported to the registry.

Similar results were found for pediatric ablation, with low percentages of total ablations (2.1%) and a wide distribution, being performed in 46% of centers. These data show that these procedures are not concentrated in selected centers, which would probably be the ideal situation.19

CONCLUSIONSThe Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry continues to systematically record the ablation procedures performed in Spain, and its track record and consistency make it the only such registry of its kind. The overall number of procedures and AF ablation procedures in particular reached a historic peak in 2018, with continued very high success rates and low rates of complications. The high participation, which was once again a peak in terms of the number of centers providing data, allows the registry to remain representative of the current situation of this procedure in Spain.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

Once again, the coordinators of the registry would like to thank all of the participants in the Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry for voluntarily and selflessly submitting their procedural data. We again extend special thanks to Cristina Plaza for her excellent and indispensable administrative work.

Jesús Almendral-Garrote, Pau Alonso-Fernández, Concepción Alonso-Martín, Nelson María Alvarenga-Recalde, Luis Álvarez-Acosta, Miguel Álvarez-López, Ignasi Anguera-Camos, Eduardo Arana-Rueda, María Fe Arcocha-Torres, Miguel Ángel Arias-Palomares, Antonio Asso-Abadía, Gabriel Alejandro Ballesteros-Derbenti, Alberto Barrera-Cordero, Juan Benezet-Mazuecos, Andrés I. Bodegas-Cañas, Josep Brugada-Terradellas, Claudia Cabadés-Rumbeu, María del Pilar Cabanas-Grandío, Sandra Cabrera-Gómez, Lucas R. Cano-Calabria, Silvia del Castillo-Arrojo, Víctor Castro-Urda, Rocío Cózar-León, Ernesto Díaz-Infante, Juan Manuel Durán-Guerrero, Juliana Elices-Teja, María del Carmen Expósito-Pineda, Juan Manuel Fernández-Gómez, Julio Jesús Ferrer-Hita, María Luisa Fidalgo-Andrés, Adolfo Fontenla-Cerezuela, Arcadio García-Alberola, J. Ignacio García-Bolao, Enrique García-Cuenca, Francisco Javier García-Fernández, Ignacio Gil-Ortega, Federico Gómez-Pulido, Juan Manuel Grande-Ingelmo, Eduard Guasch-i-Casany, José M. Guerra-Ramos, Santiago Heras-Herreros, Julio Hernández-Afonso, Benito Herreros-Guilarte, Víctor Manuel Hidalgo-Olivares, Alicia Ibáñez-Criado, José Luis Ibáñez-Criado, Sonia Ibars-Campaña, Miguel Eduardo Jáuregui-Abularach, F. Javier Jiménez-Candil, Javier Jiménez-Díaz, Jesús I. Jiménez-López, Carla Lázaro-Rivera, José Miguel Lozano-Herrera, Alfonso Macías-Gallego, Santiago Magnani-Ragamato, Javier Martínez-Basterra, Ángel Martínez-Brotons, José Luis Martínez-Sande, Gabriel Martín-Sánchez, Roberto Matías-Francés, José Luis Merino-Llorens, Josep Lluis Mont-Girbau, José Moreno-Arribas, Javier Moreno-Planas, Ángel Moya-i-Mitjans, Marta Ortega-Molina, Joaquín Osca-Asensi, Agustín Pastor-Fuentes, Ricardo Pavón-Jiménez, Rafael Peinado-Peinado, Luisa Pérez-Álvarez, Nicasio Pérez-Castellano, Rosa Porro-Fernández, Andreu Porta-Sánchez, Jordi Punti-Sala, Aurelio Quesada-Dorador, Nuria Rivas-Gándara, Gonzalo Rodrigo-Trallero, Felipe José Rodríguez-Entem, Juan Carlos Rodríguez-Pérez, Rafael Romero-Garrido, José Manuel Rubín-López, José Amador Rubio-Caballero, José Manuel Rubio-Campal, Jerónimo Rubio-Sanz, Pablo M. Ruiz-Hernández, Ricardo Salgado-Aranda, Juan Miguel Sánchez-Gómez, Georgia Sarquella-Brugada, Axel Sarrias-Mercé, Jose María Segura-Saint-Gerons, Federico Segura-Villalobos, and Irene Valverde-André.

| Andalusia | |

| Cádiz | Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (Lucas R. Cano-Calabria) |

| Granada | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada, Hospital HLA Inmaculada (Miguel Álvarez-López); Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio (José Miguel Lozano-Herrera) |

| Córdoba | Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Jose María Segura-Saint-Gerons) |

| Málaga | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Hospital Vithas Xanit Internacional, Hospital Vithas Parque San Antonio, Hospital QuirónSalud Málaga, Hospital QuirónSalud Marbella (Alberto Barrera-Cordero) |

| Sevilla | Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena (Rocío Cózar-León); Hospital Vithas Nisa Sevilla (Ernesto Díaz-Infante); Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío (Eduardo Arana-Rueda); Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme (Ricardo Pavón-Jiménez); Hospital QuirónSalud Infanta Luisa, Hospital QuirónSalud Sagrado Corazón (Juan Manuel Fernández-Gómez); Clínica HLA Santa Isabel (Rafael Romero-Garrido) |

| Aragon | |

| Zaragoza | Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Hospital QuirónSalud Zaragoza (Antonio Asso-Abadía); Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa (Gonzalo Rodrigo-Trallero) |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes (Irene Valverde-André); Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (José Manuel Rubín-López) |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Llàtzer (Santiago Magnani-Ragamato); Hospital Universitario Son Espases (María del Carmen Expósito-Pineda); Clínica Rotger, Hospital QuirónSalud Palmaplanas (Nelson María Alvarenga-Recalde) |

| Canary Islands | |

| Las Palmas | Hospital Vithas Santa Catalina (Juan Carlos Rodríguez-Pérez); Hospital Perpetuo Socorro (Pablo M. Ruiz-Hernández); Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria (Federico Segura-Villalobos) |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Luis Álvarez-Acosta); Hospital San Juan de Dios (Julio Hernández-Afonso); Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias (Julio Jesús Ferrer-Hita) |

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Felipe José Rodríguez-Entem) |

| Castile-La Mancha | |

| Toledo | Hospital Virgen de la Salud (Miguel Ángel Arias-Palomares); Hospital General Nuestra Señora del Prado (Alfonso Macías-Gallego) |

| Ciudad Real | Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real (Javier Jiménez-Díaz) |

| Albacete | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete (Víctor Manuel Hidalgo-Olivares) |

| Castile and León | |

| Burgos | Hospital Universitario de Burgos (Ricardo Salgado-Aranda) |

| Leon | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León (María Luisa Fidalgo-Andrés) |

| Salamanca | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (F. Javier Jiménez-Candil) |

| Valladolid | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (Jerónimo Rubio-Sanz); Hospital Río Hortega (Benito Herreros-Guilarte) |

| Catalonia | |

| Barcelona | Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (Ignasi Anguera-Camos); Hospital Clínic (Josep Lluis Mont-Girbau, Eduard Guasch-i-Casany); Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol (Axel Sarrias-Mercé); Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron (Nuria Rivas-Gándara); Clínica Corachán (José M. Guerra-Ramos); Clínica Sagrada Família, Hospital Universitario Dexeus (Ángel Moya-i-Mitjans); Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrassa (Sonia Ibars-Campaña); Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (Georgia Sarquella-Brugada); Hospital del Mar (Jesús I. Jiménez-López); Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí (Jordi Punti-Sala); Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Concepción Alonso-Martín) |

| Tarragona | Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII (Sandra Cabrera-Gómez, Gabriel Martín-Sánchez) |

| Lleida | Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova (Miguel Eduardo Jáuregui-Abularach) |

| Girona | Clínica Girona (Josep Brugada-Terradellas) |

| Valencian Community | |

| Alicante | Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante (José Moreno-Arribas); Hospital General Universitario de Alicante (José Luis Ibáñez-Criado); Cardioritmo Levante (Alicia Ibáñez-Criado) |

| Castellón | Hospital General Universitario de Castellón (Juan Miguel Sánchez-Gómez) |

| Valencia | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de La Fe (Joaquín Osca-Asensi); Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (Aurelio Quesada-Dorador); Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (Ángel Martínez-Brotons); Hospital de Manises (Pau Alonso-Fernández); Hospital Universitario de la Ribera (Santiago Heras-Herreros); Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset (Claudia Cabadés-Rumbeu) |

| Extremadura | |

| Badajoz | Hospital Universitario de Badajoz (Juan Manuel Durán-Guerrero) |

| Cáceres | Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara (Rosa Porro-Fernández) |

| Galicia | |

| A Coruña | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña (Luisa Pérez-Álvarez); Complexo Hospitalario Universitario Clínico de Santiago de Compostela (José Luis Martínez-Sande) |

| Pontevedra | Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro (María del Pilar Cabanas-Grandío) |

| Lugo | Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (Juliana Elices-Teja) |

| Community of Madrid | Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Javier Moreno-Planas); Hospital Universitario La Moraleja (Roberto Matías-Francés); Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Adolfo Fontenla-Cerezuela); Hospital Universitario de Getafe (Agustín Pastor-Fuentes); HM Hospitales (Jesús Almendral-Garrote); Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro (Víctor Castro-Urda); Hospital Universitario La Paz (Rafael Peinado-Peinado); Hospital Infantil La Paz (Marta Ortega-Molina); Hospital Universitario QuirónSalud Madrid y Complejo Hospitalario Ruber Juan Bravo (Andreu Porta-Sánchez, José Luis Merino-Llorens); Hospital Universitario La Paz - Unidad de Electrofisiología Robotizada, Hospital Nisa Pardo de Aravaca (José Luis Merino-Llorens); Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Nicasio Pérez-Castellano); Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (José Amador Rubio-Caballero); Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz (José Manuel Rubio-Campal); Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa (Juan Manuel Grande-Ingelmo); Hospital La Luz-Quirón (Juan Benezet-Mazuecos); Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos (Federico Gómez-Pulido); Hospital Universitario de Torrejón (Carla Lázaro-Rivera); Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada (Silvia del Castillo-Arrojo) |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Arcadio García-Alberola); Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía (Ignacio Gil-Ortega) |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (Javier Martínez-Basterra); Clínica Universidad de Navarra (Gabriel Alejandro Ballesteros-Derbenti, J. Ignacio García-Bolao) |

| Basque Country | |

| Vizcaya | Hospital de Cruces (Andrés I. Bodegas-Cañas); Hospital de Basurto (María Fe Arcocha-Torres) |

| Álava | Hospital Universitario Araba (Enrique García-Cuenca) |

| La Rioja | Hospital Viamed Los Manzanos (Francisco Javier García-Fernández) |