This article presents results of the Spanish catheter ablation registry for the year 2022.

MethodsData were retrospectively entered into a REDCap platform using a specific form.

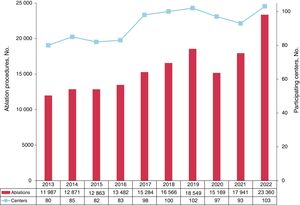

ResultsA total of 103 centers participated (75 public, 28 private), which reported 23 360 ablation procedures, with a mean of 227±173 and a median of 202 [interquartile range, 77-312] procedures per center. Activity significantly increased (+5419 procedures,+30.2%) with more centers participating in the registry (10 more than in 2021). The most common procedure continued to be atrial fibrillation ablation (35%, 8185 procedures) followed by cavotricuspid isthmus ablation (20%, 4640 procedures), and intranodal re-entrant tachycardia (17%, 3898 procedures). There was an increase in all reported substrates, especially atrial fibrillation ablation (+40%), with slightly higher global acute success (96%) and lower complication rates (1.8%) and mortality (0.04%, n=10). In total, 525 procedures were performed in pediatric patients (2.2%)

ConclusionsThe Spanish catheter ablation registry systematically and continuously collects the national trajectory, which experienced a significant activity increase in 2022 in all of the reported substrates but especially in atrial fibrillation ablation. Acute success increased, while both complications and mortality decreased.

Keywords

The Spanish catheter ablation registry, an official report of the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, details the changes over time in the interventional management of arrhythmias in Spain.1–21 Its objective is to provide structured information on the current state of catheter ablation in Spain and the safety and effectiveness associated with each ablation target. We also assess the technical approaches available, as well the staffing of the arrhythmia units in the country.

METHODSThe data for this retrospective registry of the activity of electrophysiology laboratories in Spain in 2022 were collected using a standardized form that was completed in the REDCap online platform and managed by the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Registry participation is voluntary and data are anonymized for the registry coordinators.

The registry collects information on the technical and human resources of the participating arrhythmia units and the types of procedures and ablation targets, as well as their outcomes and complications. Data were analyzed on 11 ablation targets: atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), accessory pathways (APs), atrioventricular node (AVN), focal atrial tachycardia (FAT), cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI), macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia (MAT), atrial fibrillation (AF), idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (IVT), ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia (ICM-VT), nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM-VT), and cardioneuroablation.

The variables analyzed include the number of patients and procedures (specifying the number of pediatric patients, defined as those younger than <15 years), acute success (at the end of the procedure), type of ablation catheter used, and numbers and types of complications, including periprocedural death. For certain ablation targets, we included some additional variables, such as type, location, and underlying heart disease. Also recorded were the use of electroanatomic mapping systems and procedures performed without the need for fluoroscopy. We additionally assessed the acute success rate (at the end of the procedure) and complications occurring during the hospital stay.

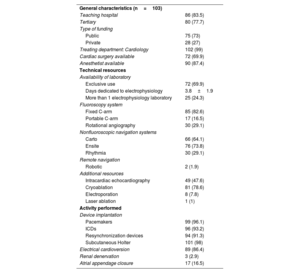

RESULTSTechnical and human resourcesThe technical and human resources available in the participating laboratories, as well as the different activities performed by them, are shown in table 1 and table 2, respectively.

Changes over time in human resources in Spanish laboratories in the last 10 years

| Variable | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff physicians | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.5 |

| Full-time physicians | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Fellows/y | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| RNs | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.4 |

| RTs | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

RN, registered nurse; RT, radiologic technologist.

Technical resources and additional activity of participating laboratories

| General characteristics (n=103) | |

| Teaching hospital | 86 (83.5) |

| Tertiary | 80 (77.7) |

| Type of funding | |

| Public | 75 (73) |

| Private | 28 (27) |

| Treating department: Cardiology | 102 (99) |

| Cardiac surgery available | 72 (69.9) |

| Anesthetist available | 90 (87.4) |

| Technical resources | |

| Availability of laboratory | |

| Exclusive use | 72 (69.9) |

| Days dedicated to electrophysiology | 3.8±1.9 |

| More than 1 electrophysiology laboratory | 25 (24.3) |

| Fluoroscopy system | |

| Fixed C-arm | 85 (82.6) |

| Portable C-arm | 17 (16.5) |

| Rotational angiography | 30 (29.1) |

| Nonfluoroscopic navigation systems | |

| Carto | 66 (64.1) |

| Ensite | 76 (73.8) |

| Rhythmia | 30 (29.1) |

| Remote navigation | |

| Robotic | 2 (1.9) |

| Additional resources | |

| Intracardiac echocardiography | 49 (47.6) |

| Cryoablation | 81 (78.6) |

| Electroporation | 8 (7.8) |

| Laser ablation | 1 (1) |

| Activity performed | |

| Device implantation | |

| Pacemakers | 99 (96.1) |

| ICDs | 96 (93.2) |

| Resynchronization devices | 94 (91.3) |

| Subcutaneous Holter | 101 (98) |

| Electrical cardioversion | 89 (86.4) |

| Renal denervation | 3 (2.9) |

| Atrial appendage closure | 17 (16.5) |

ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Values represent No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The mean number of physicians per laboratory slightly increased to 3.5 (from 3.3 in 2021), although only an average of 2.7 are full-time. There was at least 1 full-time physician in 81% of centers, at least 2 in 73%, and at least 3 in 51%. On the other hand, nursing staff numbers markedly increased, reaching an average of 3.4 (from 2.8 in 2021). Similar to previous years, 40% of units had a training program for fellows, with 1 or 2 fellows per center. In contrast, 1 center had 8 fellows.

Most centers in Spain had at least 1 dedicated cardiac electrophysiology laboratory (72 centers, 69.9%) but 24 centers (23.3%) had 2 dedicated laboratories, marking another increase from previous years (19.3% in 2021 and 22.6% in 2020); 1 center had 3 laboratories (0.97%). On average, the laboratory was available on 3.8±2 (median, 5) days a week. All centers implanted at least 1 type of cardiac device, although Holter monitors were the only devices implanted in 9 centers.

At least 1 fixed C-arm fluoroscopy system was available in 85 centers (82.6%), representing a clear increase vs previous years. Eleven centers (10.7%) had no electroanatomic mapping system, 36 (34.9%) had 2, and 22 (21.4%) had 3. The most common electroanatomic mapping systems were Ensite (73.8%) and Carto (64.1%); 47.6% of centers were equipped with intracardiac echocardiography and 29.1% with rotational angiography. Regarding alternative energy sources to radiofrequency, cryoablation was available in 78.6% of centers and electroporation in 8 (7.8%). Laser ablation was available in just 1 center, although no ablations were reported with this energy source in 2022.

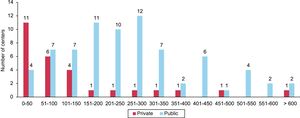

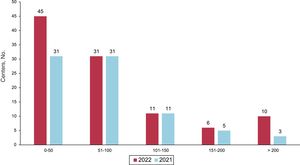

Overall resultsCompared with 2021, the number of participating centers markedly increased in 2022 (103 centers; 75 publicly funded and 28 private), with a record number of recorded ablations. A considerable fall in participating centers was detected in 2021 (to 93), attributable to the lingering effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, the number of participating centers returned in 2022 to prepandemic numbers (102 centers in the 2019 registry) while the total number of ablations markedly increased to 23 360. This represented a 30.2% increase vs 2021 and 25.9% vs 2019, which previously had the highest number of recorded ablations, with 18 549 (figure 1). The average number of ablations per center highly significantly increased to 227±173, with a median of 202 [interquartile range, 77-312]. A total of 17 centers (15 publicly funded and 2 private) performed more than 400 ablations in 2022 while just 9 centers reached these figures in 2021; 9 centers (8 publicly funded and 1 private) performed more than 500 ablations per year (figure 2).

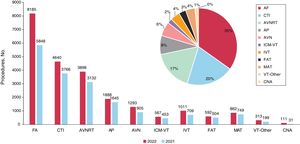

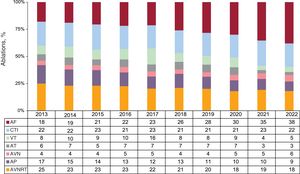

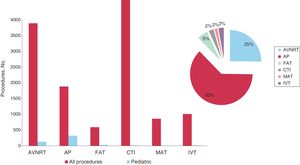

The distribution of activity per ablation target showed the same tendency as in previous years, with AF established as the most commonly treated ablation target (35%). The number of procedures exhibited a highly marked increase, reaching a record high (8185 procedures). This was once again followed by CTI ablation, which was stable at 20% (4640 procedures), and AVNRT, which represented 17% of all ablations (figure 3). An increase was detected in all ablation targets vs the 2021 registry, but the largest increase was once again seen in AF, with 2237 procedures more than in 2021 (a 40% increase). AP ablation continued its downward trend, falling to 9% of all ablation targets in 2022, whereas AVN ablation slightly increased again to 6%. Figure 4 shows the changes over time for the different ablation targets.

Distribution of the number of procedures per ablation target. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CNA, cardioneuroablation; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia; VT, ventricular tachycardia; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia.

Changes in the relative frequency of the different ablation targets treated in the last decade. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AT, atrial tachycardia (focal and atypical flutter); AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

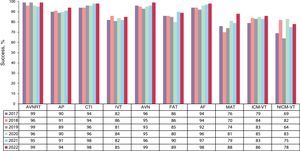

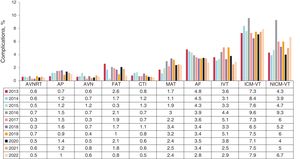

The overall success rate slightly increased to 96%, whereas the complication rate fell slightly to 1.8% and overall mortality to 0.04% (figure 5 and figure 6, respectively). In total, 422 complications were recorded; the most frequent were vascular complications (135), followed by pericardial effusion (111). Atrioventricular block (AVB) developed in 19 patients; 10 occurred during AVNRT ablation, 3 during ICM-VT, 3 during IVT, 2 during CTI, and 1 during AP ablation. There were 10 periprocedural deaths (0.04%), 6 related to AF ablation, 2 related to ICM-VT ablation, 1 related to CTI ablation, and 1 after atypical flutter ablation.

Changes in recent years in the success rate per ablation target. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; NICM-VT, nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia.

Changes over time in the complication rate per ablation target. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; NICM-VT, nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia.

The following sections detail the results obtained for the different ablation targets:

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardiaAVNRT ablation continued to be the third most commonly treated ablation target, after AF and CTI. A total of 3898 procedures were performed, representing a 24.5% increase vs 2021. Together with CTI ablation, AVNRT was once again the ablation target treated in the highest number of centers (n = 102). The reported success rate was 99% and the complication rate was 0.5%, which included 10 AVBs (0.3%), 5 vascular complications, 4 pericardial effusions, and 1 embolism. Radiofrequency was the most commonly used energy source, and cryoablation was applied in just 2.6% of procedures. Nonfluoroscopic navigation systems were used in 42.4% of procedures, most without fluoroscopy (78% of procedures with a mapping system).

Accessory pathwaysAP ablation was once again the fourth most frequently treated ablation target, with 8.1% of all ablations performed in 2022 and a 14.7% increase in the total number of procedures vs 2021 (1888 vs 1645 in 2021). AP ablation was reported by 98 of the 103 participating centers, with a success rate of 94% and complication rate of 1%. These complications included 11 vascular complications, 1 pericardial effusion, 1 pulmonary embolism, 1 AVB, and 1 intraprocedural vasospasm. In addition, 46.1% of the APs showed bidirectional conduction, 11.2% had exclusively anterograde conduction, and 42.7% had exclusively retrograde conduction. Left APs continued to be the most frequent location (50% of procedures), with a 97.6% ablation success rate, followed by inferoseptal pathways (27.5%; 96.9% reported success rate), right free wall pathways (12.4%; 89.6% success rate), and Para-Hisian/anteroseptal pathways (10.1%; 91% success rate). Epicardial ablation was necessary in 30 procedures, whereas, for the first time, transseptal access was used more than retroaortic access for ablation of the left pathways (58.7% vs 41.3%). The use of navigation systems predominated (65%), with a slight decrease from 2021 (70%), and 25.2% of procedures were performed without fluoroscopy.

Idiopathic ventricular tachycardiaIVT ablation was maintained at 4.3% of all procedures, similar to previous years. In absolute numbers (1011 procedures), a considerable increase of 42.6% was found vs 2021. After a drop in the number of centers treating this ablation target in 2021 (75 centers), the 88 centers of 2020 was once again reached, with an average of 10.3 procedures per center (range, 1-94). Regarding the locations of the tachycardias, 49% were in the right ventricular outflow tract, 18% were in the left ventricular outflow tract, 12.7% were in the aortic root, 7.4% were fascicular tachycardias, 4% were epicardial tachycardias, and 0.6% had an origin in the pulmonary artery. Finally, 8.4% were in other locations (in order of frequency): papillary muscles, mitral annulus, right ventricular free wall, tricuspid annulus, and moderator band. The reported success rate was 85% (between 70% for epicardial/coronary sinus and 91% for right ventricular outflow tract).

A navigation system was used in 88.1% of procedures and 14% were fluoroscopy free. The use of ablation catheters with an irrigated tip and contact forcesensing technology predominated for this ablation target (82%). Other energy sources were rarely used: alcohol ablation (1 procedure), cryoablation (3 procedures), and electroporation (1 procedure). Eight stereotactic radioablation procedures were reported between 2 centers. There were 29 complications (2.9%): 3 AVBs, 9 vascular complications, 14 pericardial effusions, and 1 aortic leaflet perforation.

Ventricular tachycardia associated with myocardial infarctionICM-VT ablation comprised 2.4% of all ablations performed, with 567 procedures in 539 patients. This represents an increase in both procedures (114 more) and centers (70 centers; 5 more than in 2021). The mean number of procedures was 5.5±6.3 (range, 1-27). Navigation systems were used in most procedures (91.5%) and just 14 (2.4%) were fluoroscopy free. The success rate was 86% and the most commonly used ablation catheters had an irrigated tip and contact forcesensing technology (94.5% of procedures). Two procedures were performed with stereotactic radioablation, as well as 2 with cryoablation and 1 with electroporation. An increase was detected in the use of transseptal access, reaching 66% of procedures. The combined endocardial/epicardial approach was adopted in 9% of procedures while exclusively epicardial access was used in 2.8%. The predominant strategy was ablation of the substrate (78.1% of procedures),while conventional activation mapping was applied in 21.7%. The complication rate reached 7.9%, a number similar to that of previous years: 15 vascular complications, 3 AVBs, 9 pericardial effusions, 4 embolisms, and 11 heart failure decompensations. A total of 2 deaths associated with this procedure were reported (1 electromechanical dissociation and 1 cardiogenic shock; 0.4% mortality).

Ventricular tachycardia not associated with myocardial infarctionAfter a fall in procedures and centers in 2021 (199 procedures in 45 centers), the data from 2022 showed an increase in both variables (313 procedures in 65 centers), exceeding the numbers recorded in previous years. The mean number of procedures per center was 6.8±4 (range, 1-17) and the success rate was 78%. A nonfluoroscopic navigation system was used in most procedures (91%). The substrates treated included the following: nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, 168 (73.2% success rate); arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, 65 (95% success rate); hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 11 (90.9% success rate); congenital heart disease, 27 (96.3% success rate); bundle-branch tachycardia, 8 (87.5% success rate); and miscellaneous conditions, which included Chagas disease, sarcoidosis, myocarditis, and valvular heart disease (96.3% successful).

The use of ablation catheters with an irrigated tip and contact forcesensing technology was standard (92.9%), whereas the other energy sources were rarely used: 5 alcohol ablations and 1 radioablation. A transseptal approach was used in 36.4% of procedures and retroaortic in 33.8%. The combined endocardial-epicardial approach was used in 22.3% of procedures while the exclusively epicardial approach was used in 11.5%.

The reported success rate was 6.7%: 3 vascular complications, 5 pericardial effusions, 1 embolism, 2 acute myocardial infarctions, 6 heart failure decompensations, 1 pneumothorax, 1 mediastinal puncture, and 1 oropharyngeal hemorrhage. No deaths were associated with the procedure.

Ablations in pediatric patientsA total of 525 ablations were reported in pediatric patients, which represents a 30% increase vs 2021 and indicates a progressive rise in the number of procedures in recent years. Pediatric ablations remained at 2.4% of all procedures (2.2% in 2021 and 1.6% in 2020) (figure 7). Ablations in pediatric patients were reported by 44 centers, an increase vs previous years, with considerable variation in procedures per center. The most frequently treated ablation target continued to be APs (61.5% of procedures, 323 procedures, 44 centers; range, 1-70), followed by AVNRT (24.8%, 130 procedures, 32 centers; range, 1-40) and FAT (5.3%, 28 procedures, 12 centers; range, 1-9). Other ablation targets were much less frequent in this population, such as IVT (2.7%, 14 procedures, 6 centers; range, 1-6), ICT (2.5%, 13 procedures, 4 centers; range, 1-9), MAT (1.5%, 8 procedures, 3 centers; range, 1-6), AF (0.9%, 5 procedures, only 1 center), and NICM-VT (0.8%, 4 procedures, 1 in each center). Figure 7 shows the distribution of pediatric procedures by ablation target and as a proportion of the total number of procedures.

Distribution of pediatric procedures by ablation target and as a proportion of the total number of procedures. AP, accessory pathway; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macroreentrant atrial tachycardia.

In 2022, a total of 862 procedures were performed for this ablation target (considerably more than the 749 procedures performed in 2021). This represented 3.7% of the total number of ablations in the registry. There was a notable increase in the acute efficacy of the procedure, from 79% in 2021 to 88% in 2022, probably related to refinement of the mapping and ablation techniques. In total, 21 complications were recorded (2.4% vs 3% in 2021): 4 vascular complications, 6 pericardial effusions, 1 embolism, and 3 others. One death was linked to the procedure, recorded as a consequence of an atrioesophageal fistula.

Atrial fibrillationAF ablation continued its constant growth and remained the most commonly treated ablation target. It represented 35% of all ablations (vs 33% in 2022), with a total of 8185, a huge increase from the 5848 procedures in 2021 (even though there were fewer centers participating in the registry). Of the 103 participating centers, 90 reported AF ablation (87%). Of all AF ablations, 60.5% were in patients with paroxysmal AF, 36% in patients with persistent AF, and 3.5% in patients with long-standing persistent AF; these percentages are similar to those of previous years. Overall, 97% of the ablations were considered successful. Most of the ablations (n=7966, 85%) had pulmonary vein isolation as sole objective. Other objectives included electrogram reduction at the pulmonary vein antrum (n=472; 5%), lines in the left atrium (n=509; 5%), and ablation of the superior vena cava (1%). Notably, this percentage (85%) (ie, a pulmonary vein-specific ablation strategy) was clearly lower than in 2021 (92%), which suggests that the treatment increased of ablation targets other than the pulmonary veins.

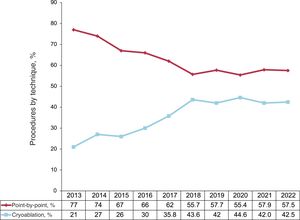

Point-by-point ablation with a radiofrequency catheter continued to slightly predominate over single-shot ablation with cryoballoons (55% and 41%, respectively), and an irrigated catheter with contact forcesensing technology was used in almost 95% of point-by-point procedures (figure 8). In addition, the first electroporation (pulse-field) ablation procedures were recorded, with a total of 244 procedures (3% of the total). Laser ablation dropped from 83 procedures in 2021 to none in 2022 and, once again, no use was recorded of the circular multielectrode catheter. In total, 280 AF ablation procedures were performed without fluoroscopy (5.7%).

In 2022, 230 complications were associated with AF ablation, 2.8% of all procedures, a notable decrease from the 3.5% in 2021. The most frequent complications were vascular (n=67) and pericardial effusion (n=63). Six deaths were reported (0.07%): 2 related to atrioesophageal fistula, 1 due to massive stroke, 1 after cardiac tamponade, 1 due to cardiogenic shock in a patient with severe left ventricular dysfunction, and 1 due to sudden cardiac death in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy and severe left ventricular dysfunction several days after the procedure.

Cavotricuspid isthmusIn 2022, 4640 CTI ablations were performed; once again, it was the second most commonly treated ablation target (19.9% of all ablations). Notably, ablation with a mapping system now predominates, increasing from 46% to 52%; in addition, 27% of CTI ablations were performed without fluoroscopy.

The procedure was successful in 98% of cases, a similar percentage to 2021, and a complication rate of 0.5% (23 procedures) was recorded, with 1 death after cardiac tamponade that required surgical drainage. Other complications included 11 vascular complications, 3 pericardial effusions, 2 AVBs, and 1 acute myocardial infarction.

Atrioventricular node ablationIn 2022, 1293 AVN ablations were performed, and it was once again the fifth most commonly treated ablation target. The success rate was 99% while the complication rate was 0.6% (n=8). As in previous years, the most frequent complications were related to vascular access (n=6). The other complications were pericardial effusion (n=1) and embolism (n=1). Just 51 of the 1293 ablations were performed with a mapping system and only 19 without fluoroscopy.

Focal atrial tachycardiaIn 2022, 592 FAT ablations were reported (2.5% of all ablations). The vast majority of FAT ablations (490 of 592 ablations; 83%) were performed with a mapping system and 25% without fluoroscopy.

The procedure was successful in 89% of cases, similar to 2021. Five complications (0.8%) were reported; the more frequent were those related to the vascular access (n=3), as well as 1 pericardial effusion and 1 myocardial infarction. Notably, the absence of AVB during the ablation was reported in 2022, except for 1 transient AVB.

Mapping systems and zero-fluoroscopy ablationThe percentage of ablation procedures performed with nonfluoroscopic navigation systems grew once again, from 52% in 2021 to 55% in 2022 (12 858 procedures). The use of a mapping system dominated for MAT (94% of procedures), FAT (83%), and VT (88% of idiopathic VTs, 92% of postinfarction VTs, and 91% of nonischemic cardiomyopathy-related VTs). More intermediate percentages were reported for AVNRT (42%), AP (61%), and ICT (52%). Mapping systems were rarely used for AVN ablation (4%).

The number of procedures performed without fluoroscopy increased to 3676 and was maintained at 16% overall. The ablation targets most commonly treated without fluoroscopy were AVNRT, CTI, and FAT (33%, 27%, and 25%, respectively), with a gradual increase in AP ablation procedures (23%). Fluoroscopy-free procedures were rare for the remaining ablation targets.

Despite the inclusion of cardioneuroablation in the registry, no information was provided on the use of mapping systems and fluoroscopy-free procedures.

DISCUSSIONThe data for 2022 from the Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry show a clear recovery in center participation, which reached a record high of 103. This represents 1 more center than the previous record, set in 2019, just before the pandemic. One of the main reasons for this participation recovery is undoubtedly the complete return to normal activity in arrhythmia units, after several years in which they have been affected by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In addition, this year's registry has seen a major change in the data collection method because, for the first time, the responsible person in each center directly submitted the data via the REDCap online platform. This new method permits smoother and more reproducible data collection, is less susceptible to entry errors, and significantly increases the possible exploitation of the information gathered.

A highly significant increase in activity was detected in 2022, with a total of 23 360 ablation procedures. This represents an activity increase of 30.2% vs 2021 (5419 procedures more than in 2020). The increase in the number of participating centers (103 vs 93 in 2020) cannot solely explain the highly marked increase in the number of procedures because it still exceeds the previous maximum of 2019 by 4800, despite very similar numbers of participating centers. This means that arrhythmia units have significantly increased their activity. This is reflected in the average number of ablations per center, which has reached 227 (193 in 2021), and in the number of centers performing more than 400 ablations per year, which has jumped from 9 in 2021 to 17 in 2022.

The treatment of all ablation targets increased in 2022, but particularly striking growth was seen for AF. The number of such procedures has reached 8185, which represents 40% more than in 2021 (5848 procedures) and mirrors a tendency that has also been detected in other countries.22 Thirteen centers now perform more than 200 AF ablations per year and 24 more than 150 (figure 9). While AF was consolidated as the most commonly treated ablation target and shows continued growth, ICT and AVNRT ablation were maintained in the second and third places, respectively, with stable figures. AP ablation continues its gradual decrease and, for the first time, represented <10% of all ablations (9%). The other ablation targets remained stable, with AVN ablation showing a slight increase in recent years, reaching 6%. This trend could be explained by the development and boom in conduction system pacing, which has somehow reduced the threshold for AVN ablation due to the availability of a permanent physiological pacing technique.23 Cardioneuroablation, an ablation target included in the registry for the first time in 2021, grew significantly, from 31 procedures in 2021 to 131 in 2022.24

A notable finding from the 2022 registry data is that the overall success rate slightly increased to 96%, concurrent with falls in complication and mortality rates to 1.8% and 0.4%, respectively. This trend could be explained by the growth in the average number of ablations per center, given that operator experience is directly associated with ablation outcomes and complication development. Although the data show that ablation is a safe procedure, complications are not negligible and must be considered. Therefore, characterization and follow-up should be improved to reduce these figures even further.

CONCLUSIONSThe Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry has systematically and reliably collected data on the activity and resources of arrhythmia units in Spain for more than 2 decades. Arrhythmia unit activity highly significantly increased in 2022 in Spain for all ablation targets but particularly for AF. The acute success rate increased and complications and mortality fell.

FUNDINGNo funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSBoth the primary author, Ó. Cano, and the coauthors V. Bazán and E. Arana have fully contributed to the design of the study and to the data analysis, manuscript drafting, and manuscript revision.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors have no conflicts of interests in relation to this article.

The coordinators of the registry would once again like to thank all of the participants in the Spanish catheter ablation registry, whose selfless help every year permit the publication of this document. We thank Javier Martínez Marín for his invaluable assistance with the data collection and organization, as well as the Information Technology and Communication Department of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

Óscar Alcalde-Rodríguez, Jesús Almendral-Garrote, Pau Alonso-Fernández, Miguel Álvarez-López, Luis Álvarez-Acosta, Ignasi Anguera-Camos, Álvaro Arce-León, Ángel Arenal, Miguel Ángel Arias Palomares, María Fe Arocha-Torres, Antonio Asso-Abadía, Alberto Barrera-Cordero, Pablo Bastos-Amador, Juan Benezet-Mazuecos Eva María Benito-Martínez, Bruno Bochard-Villanueva, Pilar Cabanas-Grandío, Mercedes Cabrera-Ramos, Lucas R. Cano-Calabria, Silvia del Castillo-Arrojo, Alba Cerveró, Tomás Datino-Romaniega, Ernesto Díaz-Infante, Eloy Domínguez-Mafé, Juan Manuel Durán-Guerrero, Juliana Elices Teja, María Emilce-Trucco, Hildemari Espinosa-Viamonte, Óscar Fabregat-Andrés, Gonzalo Fernández-Palacios, Ignacio Fernández-Lozano, Juan Manuel Fernández-Gómez, Julio Jesús Ferrer-Hita, María Luisa Fidalgo-Andrés, Enrique García-Cuenca, Daniel García-Rodríguez, Francisco Javier García-Fernández, Ignacio Gil-Ortega, Federico Gómez-Pulido, Juan José González-Ferrer, Carlos Eugenio Grande-Morales, Eduard Guasch-Casany, José María Guerra-Ramos, Benito Herreros-Guilarte, Víctor Manuel Hidalgo-Olivares, Alicia Ibáñez-Criado, José Luis Ibáñez-Criado, Francisco Javier Jiménez-Díaz, Jesús Jiménez-López, Javier Jiménez-Candil, Vanesa Cristina Lozano-Granero, Antonio Óscar Luque-Lezcano, Julio Martí-Almor, Gabriel Martín-Sánchez, José Luis Martínez-Sande, Ángel Miguel Martínez-Brotons, Francisco Mazuelos-Bellido, Haridian Mendoza-Lemes, Diego Menéndez-Ramírez, José Luis Merino-Llorens, José Moreno-Arribas, Pablo Moriña-Vázquez, Ignacio Mosquera-Pérez, Ángel Moya-Mitjans, Joaquín Osca-Asensi, Agustín Pastor-Fuentes, Ricardo Pavón-Jiménez, Alonso Pedrote-Martínez, Rafael Peinado-Peinado, Antonio Peláez-González, Pablo Peñafiel-Verdú, Víctor Pérez-Roselló, Andreu Porta-Sánchez, Javier Portales-Fernández, Aurelio Quesada-Dorador, Pablo Ramos-Ardanaz, Nuria Rivas-Gándara, Felipe José Rodríguez-Entem, Enrique Rodríguez-Font, Daniel Rodríguez-Muñoz, Rafael Romero-Garrido, José Manuel Rubín-López, José Amador Rubio-Caballero, José Manuel Rubio-Campal, Ana Delia Ruíz-Duthil, Pablo M. Ruíz-Hernández, Íñigo Sainz-Godoy, Ricardo Salgado-Aranda, Óscar Salvador-Montañés, Pepa Sánchez-Borque, María de Gracia Sandín-Fuentes, Georgia Sarquella-Brugada, Axel Sarrias-Mercè, Assumpció Saurí-Ortiz, Federico Segura-Villalobos, Irene Valverde-André, and Iván Vázquez-Esmorís.

| Andalusia | |

| Cádiz | Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar (Lucas Cano Calabria) |

| Córdoba | Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Francisco Mazuelos Bellido) |

| Granada | Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio (Ana Delia Ruíz Duthil); Hospital HLA Inmaculada (Miguel Álvarez López); Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves (Miguel Álvarez López) |

| Huelva | Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (Pablo Moriña Vázquez); Hospital QuirónSalud Huelva (Juan Manuel Fernández Gómez) |

| Málaga | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria (Alberto Barrera Cordero); Hospital QuirónSalud Málaga (Alberto Barrera Cordero); Hospital QuirónSalud Marbella (Alberto Barrera Cordero); Hospital Vithas Málaga (Alberto Barrera Cordero); Hospital Vithas Xanit Internacional Benalmádena (Alberto Barrera Cordero) |

| Seville | Clínica HLA Santa Isabel (Álvaro Arce León); Hospital QuirónSalud Infanta Luisa (Rafael Romero Garrido); Hospital Vithas Sevilla (Ernesto Díaz Infante); Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme (Ricardo Pavón Jiménez); Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Alonso Pedrote Martínez); Hospital Virgen Macarena (Pablo Bastos Amador, Ernesto Díaz Infante); QuirónSalud Sagrado Corazón (Juan Manuel Fernández Gómez) |

| Aragon | Hospital Lozano Blesa (Mercedes Cabrera Ramos); Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (Antonio Asso Abadía); QuirónSalud Zaragoza (Antonio Asso Abadía) |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes (Irene Valverde André); Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (José Manuel Rubín López) |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases (Carlos Eugenio Grande Morales) |

| Canary Islands | |

| Las Palmas | Hospital Perpetuo Socorro (Pablo M. Ruiz Hernández); Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín (Haridian Mendoza Lemes); Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria (Federico Segura Villalobos) |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias (Julio Jesús Ferrer Hita); Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria (Luis Álvarez Acosta) |

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Felipe José Rodríguez Entem) |

| Castile and León | |

| Burgos | Hospital Universitario de Burgos (Francisco Javier García Fernández, Gonzalo Fernández Palacios) |

| León | Hospital de León (María Luisa Fidalgo Andrés) |

| Salamanca | Hospital Universitario de Salamanca (Javier Jiménez Candil) |

| Valladolid | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (María de Gracia Sandín Fuentes); Hospital Universitario Río Hortega (Benito Herreros Guilarte) |

| Castile-La Mancha | |

| Albacete | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete (Víctor Manuel Hidalgo Olivares) |

| Ciudad Real | Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real (Francisco Javier Jiménez Díaz) |

| Toledo | Hospital Universitario de Toledo (Miguel Ángel Arias Palomares) |

| Catalonia | |

| Barcelona | Clínica Corachán (José María Guerra Ramos); Clínica Sagrada Família (Andreu Porta Sánchez); Centro Médico Teknon (Julio Martí Almor, Enrique Rodríguez Font); Hospital Clínic (Eduard Guasch Casany); Hospital del Mar (Jesus Jiménez López); Hospital San Joan de Déu (Georgia Sarquella Brugada); Hospital de la Santa Cruz y San Pablo (Enrique Rodríguez Font); Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (Ignasi Anguera); Hospital Universitario Dexeus (Ángel Moya Mitjans); Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (Axel Sarrias Mercè); Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron (Nuria Rivas Gándara) |

| Girona | Hospital Universitario Doctor Josep Trueta (Eva María Benito Martín, María Emilce Trucco) |

| Lleida | Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova (Hildemari Espinosa Viamonte, Diego Menéndez Ramírez) |

| Tarragona | Unidad Funcional Territorial de Electrofisiología Camp de Tarragona (Gabriel Martín Sánchez) |

| Valencian Community | |

| Alicante | Cardioritmo Levante: Hospital HLA La Vega, Clínica HLA Vistahermosa, Hospitales IMED Elche y Benidorm (Alicia Ibáñez Criado); Hospital General Universitario de Alicante Doctor Balmis (José Luis Ibáñez Criado); Hospital San Juan de Alicante (José Moreno Arribas) |

| Castellón | Hospital Universitario General de Castellón (Víctor Pérez Roselló) |

| Valencia | Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia (Assumpció Saurí Ortiz); Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (Eloy Domínguez Mafé, Ángel Martínez Brotons); Hospital de Manises (Pau Alonso Fernández); Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (Aurelio Quesada Dorador, Alba Cerveró); Hospital IMED de Valencia (Óscar Fabregat Andrés); Hospital Universitario de la Ribera (Bruno Bochard Villanueva); Hospital Universitari Doctor Peset (Antonio Peláez González); Hospital Universitario La Fe (Joaquín Osca Asensi) |

| Extremadura | |

| Badajoz | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz (Juan Manuel Durán Guerrero) |

| Cáceres | Hospital de Cáceres (Javier Portales Fernández) |

| Galicia | |

| A Coruña | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña (Luisa Pérez Álvarez); Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela (José Luis Martínez Sande); Hospital HM Modelo La Coruña (Ignacio Mosquera Pérez) |

| Pontevedra | Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro (Pilar Cabanas Grandío) |

| Lugo | Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (Juliana Elices Teja) |

| Community of Madrid | Fundación Jiménez Díaz (José Manuel Rubio Campal); Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Ricardo Salgado Aranda); Hospital Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda (Ignacio Fernández Lozano, Daniel García Rodríguez); Hospital La Luz (Juan Benezet Mazuecos); Clínica Ruber Juan Bravo (José Luis Merino Llorens); Hospital Universitario de Getafe (Agustín Pastor Fuentes); Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Daniel Rodríguez Muñoz); Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada (Silvia del Castillo Arrojo); Hospital Universitario (General e Infantil) La Paz, Unidad de Electrofisiología Robotizada (José Luis Merino Llorens); Hospital Universitario La Paz, Unidad de Arritmias (Rafael Peinado Peinado); Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (José Amador Rubio Caballero); Hospital Universitario General de Villalba (José Manuel Rubio Campal); Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Ángel Arenal); Hospital Universitario de Torrejón (Óscar Salvador Montañés); Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena (Federico Gómez Pulido); Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe (Jesús Almendral Garrote); Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias (Juan José González Ferrer); Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Vanesa Cristina Lozano Granero); Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos (Federico Gómez Pulido); Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa (Ricardo Salgado Aranda); Hospital Universitario QuirónSalud Madrid y Complejo Hospitalario Ruber Juan Bravo (Tomás Datino Romaniega); Viamed Santa Elena (José Luis Merino Llorens) |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital Universitario Santa Lucía (Ignacio Gil Ortega); Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Pablo Peñafiel Verdú) |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Clínica Universidad de Navarra (Pablo Ramos Ardanaz); Hospital Universitario de Navarra (Óscar Alcalde Rodríguez) |

| La Rioja | Hospital San Pedro La Rioja (Pepa Sánchez Borque) |

| Basque Country | |

| Álava | Hospital Universitario de Álava (Enrique García Cuenca) |

| Guipúzcoa | Hospital Universitario de Donostia (Antonio Óscar Luque Lezcano) |

| Vizcaya | Hospital de Basurto (María Fe Arcocha Torres); Hospital de Cruces (Íñigo Sainz Godoy) |

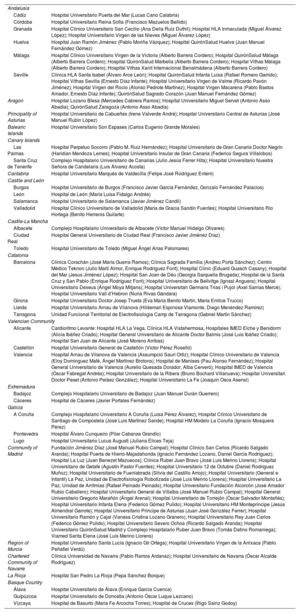

The collaborators are listed in appendix 1 while the participating electrophysiology laboratories are shown in appendix 2.