The present article reports the characteristics and results of heart transplants in Spain since this therapeutic modality was first used in May 1984.

MethodsWe summarize the main features of recipients, donors, surgical procedures, and outcomes of all cardiac transplants performed in Spain up to December 31, 2016.

ResultsA total of 281 cardiac transplants were performed in 2016. The whole historical series consisted of 7869 procedures. The main features of transplant procedures in 2016 were similar to those observed in recent years. A high percentage of procedures were urgent, particularly those with use of pretransplant continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (19.1% of all transplants). Survival significantly improved in the last decade compared with previous periods.

ConclusionsDuring the last few years, transplant activity in Spain has remained steady, with approximately 250-300 transplants/year. Despite a more complex clinical context, survival has improved in recent years.

Keywords

As in previous years, we present the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (Registro Español de Trasplante Cardiaco [RETC]), containing the updated data related to the heart transplant activity performed in 2016 in Spain.1–27 The Registry reports the clinical characteristics and the outcome of transplant procedures. The continuous updating of information since May 1984, as well as the use of a common database created by consensus, provides an overall perspective of this important clinical activity that enables detection of potential shortcomings and areas for improvement.

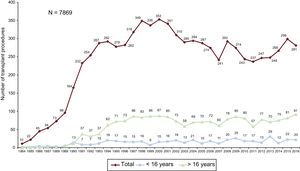

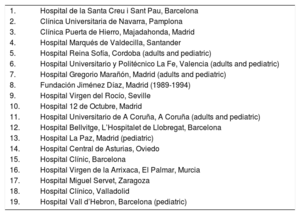

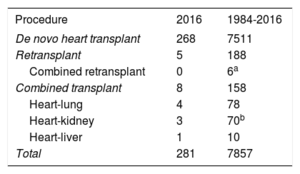

METHODSPatients and CentersOf the 19 centers that have contributed data to the RETC, 18 are now currently active (Table 1). Two centers are exclusively devoted to pediatric transplant procedures, whereas 4 others carry out transplants in both pediatric patients and adults. The number of procedures performed per year is shown in Figure 1. The total activity recorded in the Registry comprises 7869 procedures. Data were missing for 12 procedures, including follow-up information. These were omitted from the analysis, which left a final sample of 7857 transplant surgeries. Of 281 procedures carried out in 2016, 20 (7.1%) were performed in pediatric patients (age < 16 years). The types of procedures performed in 2016 and in the total recorded series are summarized in Table 2.

Centers Participating in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry by Order of First Transplant Performed (1984-2016)

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona |

| 2. | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona |

| 3. | Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid |

| 4. | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía, Cordoba (adults and pediatric) |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia (adults and pediatric) |

| 7. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adults and pediatric) |

| 8. | Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (1989-1994) |

| 9. | Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville |

| 10. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid |

| 11. | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña (adults and pediatric) |

| 12. | Hospital Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona |

| 13. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid (pediatric) |

| 14. | Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo |

| 15. | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona |

| 16. | Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia |

| 17. | Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza |

| 18. | Hospital Clínico, Valladolid |

| 19. | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona (pediatric) |

The database includes 175 clinical variables established by consensus among all the transplant teams. The variables include data on the recipient, donor, surgical technique, immunosuppression used, and the follow-up. Since 2013, the data have been electronically recorded and updated in real time using a web-based program specifically designed for this purpose. The data are provided in a Microsoft Excel file. This system replaces the previous one, in which each center sent data to the Registry director by e-mail in a Microsoft Access file. An external contract research organization (CRO), currently ODDS S.L., carries out database maintenance, quality assurance, and the statistical analyses.

Ethics committee approval, auditing, and registration with the Spanish Ministry of Health were done in keeping with the requirements set down in the Organic Law on Data Protection 15/1999.

StatisticsContinuous quantitative variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as percentages. The results were categorized according to the year of transplant, with the overall sample being divided into 4 time periods (1984-1993, 1994-2003, 2004-2013, and 2014-2015). Certain variables were also analyzed according to the yearly data from the series, such as donor age, urgent transplant, and ischemia time. Differences between groups were analyzed using a nonparametric test for temporal trends (Kendall tau) for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with polynomial fitting for continuous variables. Survival curves were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using a log rank test. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant in the comparisons.

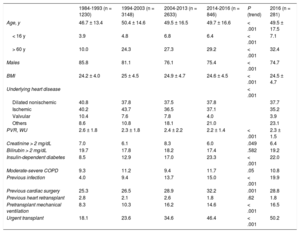

RESULTSRecipient CharacteristicsIn 2016, the mean age of the recipients was 49.5±17.5 (range, 0.18-72) years. Males accounted for 74.7%, and the main baseline diagnoses were ischemic cardiomyopathy (35.2%), nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (29.2%), valvular cardiomyopathy (3.9%), and other diagnoses (31.7%). The characteristics of the recipients by transplant period are summarized in Table 3. The age and sex of recipients has remained stable over the last 2 decades. Significant trends were seen toward an increase in unusual underlying heart disease and in pretransplant conditions having a recognized prognostic effect, such as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and infection, as well as cardiac surgery and mechanical ventilation prior to transplant. Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, the percentage of retransplants fell below 2% from 2014 to 2016, and accounted for 2.4% of the total series. In contrast, there was a significant decrease in pretransplant pulmonary vascular resistance values and a decrease approaching significance in severe pretransplant renal impairment over time in the total sample.

Recipient Characteristics in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry(1984-2016)

| 1984-1993 (n = 1230) | 1994-2003 (n = 3148) | 2004-2013 (n = 2633) | 2014-2016 (n = 846) | P (trend) | 2016 (n = 281) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 46.7 ± 13.4 | 50.4 ± 14.6 | 49.5 ± 16.5 | 49.7 ± 16.6 | < .001 | 49.5 ± 17.5 |

| < 16 y | 3.9 | 4.8 | 6.8 | 6.4 | < .001 | 7.1 |

| > 60 y | 10.0 | 24.3 | 27.3 | 29.2 | < .001 | 32.4 |

| Males | 85.8 | 81.1 | 76.1 | 75.4 | < .001 | 74.7 |

| BMI | 24.2 ± 4.0 | 25 ± 4.5 | 24.9 ± 4.7 | 24.6 ± 4.5 | < .001 | 24.5 ± 4.7 |

| Underlying heart disease | < .001 | |||||

| Dilated nonischemic | 40.8 | 37.8 | 37.5 | 37.8 | 37.7 | |

| Ischemic | 40.2 | 43.7 | 36.5 | 37.1 | 35.2 | |

| Valvular | 10.4 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 4.0 | 3.9 | |

| Others | 8.6 | 10.8 | 18.1 | 21.0 | 23.1 | |

| PVR, WU | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.2 ± 1.4 | < .001 | 2.3 ± 1.5 |

| Creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 7.0 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 6.0 | .049 | 6.4 |

| Bilirubin > 2 mg/dL | 19.7 | 17.8 | 18.2 | 17.4 | .582 | 19.2 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 8.5 | 12.9 | 17.0 | 23.3 | < .001 | 22.0 |

| Moderate-severe COPD | 9.3 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 11.7 | .05 | 10.8 |

| Previous infection | 4.0 | 9.4 | 13.7 | 15.0 | < .001 | 19.9 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 25.3 | 26.5 | 28.9 | 32.2 | .001 | 28.8 |

| Previous heart retransplant | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 1.8 | .62 | 1.8 |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 8.3 | 10.3 | 16.2 | 14.6 | < .001 | 16.5 |

| Urgent transplant | 18.1 | 23.6 | 34.6 | 46.4 | < .001 | 50.2 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Data are expressed as the percentage or the mean ± standard deviation.

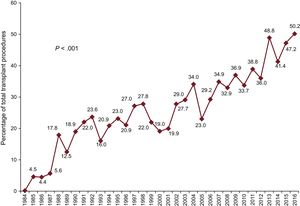

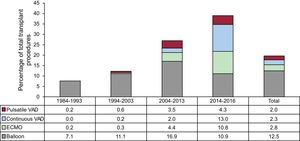

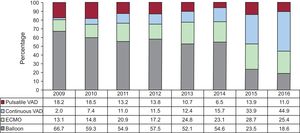

In 2016, urgent transplant accounted for more than 50% of the procedures. This maintains a trend observed since 2013, with urgent transplants being performed in more than 40% of patients (Figure 2). The increasing use of pretransplant ventricular assist devices detected since 2009 was also confirmed in 2016 (P < .001) (Figure 3). Furthermore, 2016 showed a predominance of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices (44.9%) and a reduction in the use of pretransplant balloon pumps (Figure 4).

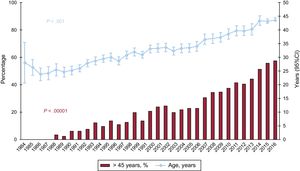

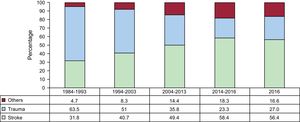

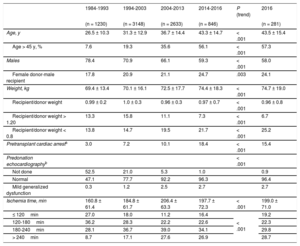

The characteristics of the donors by time period and in 2016 are summarized in Table 4. Donor age has significantly increased throughout the total recorded series, and in 2016, 57% of donors were in the age range considered suboptimal (> 45 years) (Figure 5). The percentage of transplant surgeries performed with grafts from female donors to male recipients was somewhat lower in 2016 (24.1%) than in 2015 (26.4%). Furthermore, there was an increase in donors who died due to stroke and a decrease in those who died due to trauma (Figure 6).

Donor Characteristics and Ischemia Time in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (1984-2016)

| 1984-1993 | 1994-2003 | 2004-2013 | 2014-2016 | P (trend) | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1230) | (n = 3148) | (n = 2633) | (n = 846) | (n = 281) | ||

| Age, y | 26.5 ± 10.3 | 31.3 ± 12.9 | 36.7 ± 14.4 | 43.3 ± 14.7 | < .001 | 43.5 ± 15.4 |

| Age > 45 y, % | 7.6 | 19.3 | 35.6 | 56.1 | < .001 | 57.3 |

| Males | 78.4 | 70.9 | 66.1 | 59.3 | < .001 | 58.0 |

| Female donor-male recipient | 17.8 | 20.9 | 21.1 | 24.7 | .003 | 24.1 |

| Weight, kg | 69.4 ± 13.4 | 70.1 ± 16.1 | 72.5 ± 17.7 | 74.4 ± 18.3 | < .001 | 74.7 ± 19.0 |

| Recipient/donor weight | 0.99 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.96 ± 0.3 | 0.97 ± 0.7 | < .001 | 0.96 ± 0.8 |

| Recipient/donor weight > 1.20 | 13.3 | 15.8 | 11.1 | 7.3 | < .001 | 6.7 |

| Recipient/donor weight < 0.8 | 13.8 | 14.7 | 19.5 | 21.7 | < .001 | 25.2 |

| Pretransplant cardiac arresta | 3.0 | 7.2 | 10.1 | 18.4 | < .001 | 15.4 |

| Predonation echocardiographyb | < .001 | |||||

| Not done | 52.5 | 21.0 | 5.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

| Normal | 47.1 | 77.7 | 92.2 | 96.3 | 96.4 | |

| Mild generalized dysfunction | 0.3 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | |

| Ischemia time, min | 160.8 ± 61.4 | 184.8 ± 61.7 | 206.4 ± 63.3 | 197.7 ± 72.3 | < .001 | 199.0 ± 71.0 |

| ≤ 120min | 27.0 | 18.0 | 11.2 | 16.4 | < .001 | 19.2 |

| 120-180min | 36.2 | 28.3 | 22.2 | 22.6 | 22.3 | |

| 180-240min | 28.1 | 36.7 | 39.0 | 34.1 | 29.8 | |

| > 240min | 8.7 | 17.1 | 27.6 | 26.9 | 28.7 |

Data are expressed as the percentage or the mean ± standard deviation.

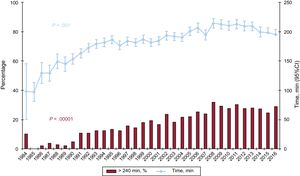

The ischemia time has risen throughout the total recorded series. As in the previous decade, more than one-quarter of the patients underwent transplant with an ischemia time greater than 240minutes in 2016 (Table 4 and Figure 7).

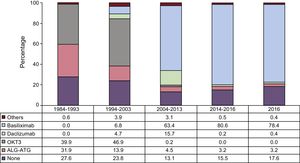

ImmunosuppressionIn 2016, 82.4% of recipients received some type of induction immunosuppressive therapy, mainly basiliximab (78.4%) (Figure 8), confirming a trend described in previous reports and observed since 2009.

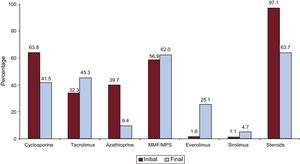

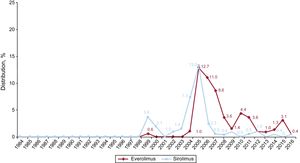

A summary of the immunosuppressive drugs used initially and at completion of follow-up in the total recorded series is provided in Figure 9. At a mean follow-up of 7.3 years, 63.7% of patients continued receiving corticosteroid therapy, and at the last follow-up, 30% of patients were under treatment with mTOR inhibitors (everolimus or sirolimus).

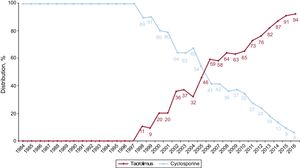

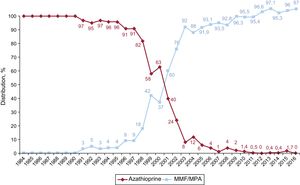

In 2016, the initial immunosuppressive regimen mainly consisted of tacrolimus (91.1%) as a calcineurin inhibitor, mycophenolate mofetil or mycophenolic acid (97.0%) as an antiproliferative agent, and steroids (98.9%). Yearly changes in the use of calcineurin inhibitors and antimitotic agents for initial immunosuppression are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively, whereas changes in the use of mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus) are shown in Figure 12.

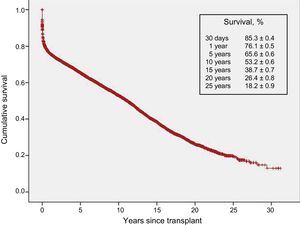

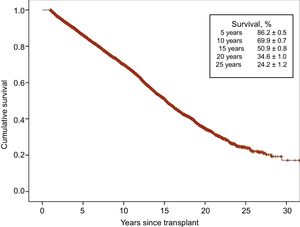

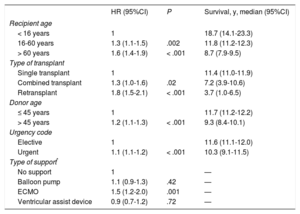

With the latest update on 31 December 2016, actuarial survival in the total recorded series at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years is depicted in Figure 13. The findings indicate a mean yearly mortality rate of around 2% to 3% after the first year after transplant, with a median survival of 11.2 years. The 1-year conditional survival curve is shown in Figure 14. The conditional median survival after the first posttransplant year was 15.1 years. As shown in Table 5, there were significant differences in recipient age, donor age, type of procedure (single transplant, combined transplant, and retransplant), the urgency code for transplant, and the type of circulatory support at the time of transplant (no support, balloon pump, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO], ventricular assist device), similar to the findings from the previous year. Of particular note, survival rates were comparable in patients undergoing elective transplant and those undergoing transplant with balloon pumps or ventricular assist devices. Survival was significantly lower in transplant procedures performed in patients with previous ECMO than in those with no devices.

Univariate Survival Analysis by Baseline Characteristics of the Recipient, Donor, and Procedure (1984-2016)

| HR (95%CI) | P | Survival, y, median (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient age | |||

| < 16 years | 1 | 18.7 (14.1-23.3) | |

| 16-60 years | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | .002 | 11.8 (11.2-12.3) |

| > 60 years | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | < .001 | 8.7 (7.9-9.5) |

| Type of transplant | |||

| Single transplant | 1 | 11.4 (11.0-11.9) | |

| Combined transplant | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | .02 | 7.2 (3.9-10.6) |

| Retransplant | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | < .001 | 3.7 (1.0-6.5) |

| Donor age | |||

| ≤ 45 years | 1 | 11.7 (11.2-12.2) | |

| > 45 years | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | < .001 | 9.3 (8.4-10.1) |

| Urgency code | |||

| Elective | 1 | 11.6 (11.1-12.0) | |

| Urgent | 1.1 (1.1-1.2) | < .001 | 10.3 (9.1-11.5) |

| Type of support* | |||

| No support | 1 | — | |

| Balloon pump | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | .42 | — |

| ECMO | 1.5 (1.2-2.0) | .001 | — |

| Ventricular assist device | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | .72 | — |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval, ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HR, hazard ratio.

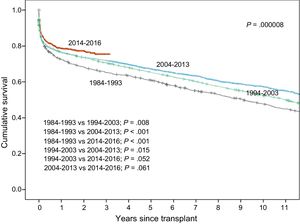

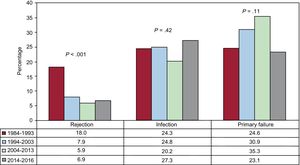

Survival rates have shown a steady increase throughout the total recorded series (Figure 15). Significant differences were found for the decade from 1984 to 1993 relative to later decades and for the period from 2014 to 2016. Compared with the first decade, the superior survival in later years was mainly attributable to increased survival in the first year after transplant. Nonetheless, starting from the decade from 2004 to 2013, survival rates after the second posttransplant year also showed an improvement. In the most recent period (2014-2016), a trend to greater early and longer-term survival was detected, although statistical significance was not reached because of the relatively small available sample size.

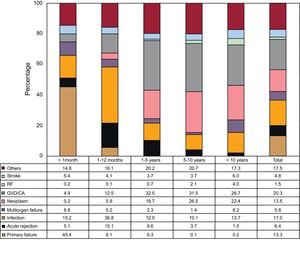

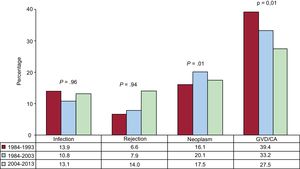

Causes of DeathIn the total series, the most common cause of death was graft vascular disease/cardiac arrest (20.3%), followed by infection (17.0%), neoplasm (13.5%), and primary graft failure (13.3%) (Figure 16). The causes of death varied according to the time considered following transplant (Figure 16). In the first posttransplant month, nearly half the deaths were due to primary graft failure. From the first month to the end of the first year, the main causes of death were acute rejection (15.1%) and particularly infections (36.8%). After the first year, the main causes were the various manifestations of graft vascular disease (29.9%) and tumors (22.5%). The main causes of death at 1 year have changed significantly over time, with a drop in cardiac arrests due to acute rejection and a rise in deaths caused by primary graft failure, although this latter event showed a decrease in the period from 2014 to 2016 (Figure 17). Analysis of mortality occurring between the first and fifth year following transplantshowed a significant decrease in deaths caused by graft vascular disease/cardiac arrest and a significant increase in deaths due to acute rejection (Figure 18).

The data compiled up to 2016 on heart transplant in Spain confirm the trends observed in previous years regarding the procedural characteristics and survival results. The period from 2014 to 2016 has shown a strong trend to improved survival relative to the previous decade, although the results have not reached statistical significance because of the relatively small sample size of this period. The improvement is evident in both short- and mid-term survival rates. In the first year after transplant, mortality caused by acute rejection has been controlled and there is a strong trend toward control of mortality due to primary graft failure. Beyond the first year, and awaiting data from expanded follow-up in the coming years, there is already evidence of better control of mortality due to graft vascular disease and cardiac arrest (the latter considered a manifestation of graft vascular disease in the immediate posttransplant period in most cases). In absolute numbers, deaths due to acute rejection far exceed those resulting from these 2 causes during this period.

In procedures as complex as heart transplant, improvements in outcome can hardly be attributed to a single cause. It is true that in general terms there is a trend over time to perform transplant surgery in patients in an apparently poorer clinical condition (eg, a larger number of urgent procedures, patients intubated and having undergone previous surgeries, pretransplant infections, and pretransplant circulatory support devices). However, the expanded use of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices before transplant and the subsequent decrease in ECMO use has led to patients having a more satisfactory pretransplant clinical status, including, for example, better renal function. The availability of circulatory support in the immediate postoperative period is undoubtedly a contributing factor to the decrease in deaths due to primary graft failure, a complication that is typically reversible in a few hours or days if the patient can be kept alive with these devices. After the first year after transplant, successful control of mortality from graft vascular disease likely lies in better knowledge of pathophysiological factors, the treatment used (eg, lipid-lowering, antihypertensive, and antiplatelet therapies, and control of early rejection and cytomegalovirus infection), and the availability of immunosuppressive agents with recognized antiproliferative activity (eg, mTOR inhibitors, which are being widely used according to the available data).

Of particular note, these favorable results are being obtained despite the acceptance of donors until recently considered only marginally suitable. The expanded accepted age of donors is especially striking, and for the time being, this factor does not seem to affect mid-term survival in a quantitatively relevant manner.

CONCLUSIONSThis 2016 RETC update does not show substantial differences with respect to reports from the immediately preceding years regarding the number of transplant surgeries performed or the characteristics of the donors, recipients, and procedures. The survival results continue to show a gradual improvement in transplant procedures performed in the most recent years.

FUNDINGThe RETC is partially funded by an unconditional grant from Novartis.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

We thank ODDS S.L. for their statistical support. Many of the participating researchers and centers are part of the Red de Investigación Cardiovascular of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

| Clínica Universitaria Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid | Luis Alonso-Pulpón, Javier Segovia-Cubero, Francisco Hernández-Pérez, Alberto Forteza-Gil, Santiago Serrano-Fiz, Raúl Burgos-Lázaro, Carlos García-Montero, Carlos E. Martín-López, Susana Villar-García |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia | Soledad Martínez, Mónica Cebrián, Raquel López, Ignacio Sánchez, Luis Martínez |

| Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña | María J. Paniagua-Martín, Eduardo Barge-Caballero, Gonzalo Barge-Caballero, David Couto-Mallón |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Cordoba | Amador López-Granados, Carmen Segura-Saintgerons, Dolores Mesa, Martín Ruiz, Elías Romo, Francisco Carrasco, José López Aguilera |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander | Manuel Cobo, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, Jose A. Vázquez de Prada, Francisco Nistal Herrera |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón (adults), Madrid | Paula Navas, Eduardo Zataraín, María Jesús Valero, Juan Fernández Yáñez, Adolfo Villa, Manuel Martínez-Sellés |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | María Dolores García-Cosío, Laura Morán-Fernández, Carlos Ortiz-Bautista, Enrique Pérez-de la Sota |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Sònia Mirabet, Eulàlia Roig y Laura López |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville | Ernesto Lage-Gallé, Diego Rangel-Sousa, Antonio Grande-Trillo |

| Hospital Universitario Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | Nicolás Manito-Lorite, Carles Díez-López, Josep Roca Elías |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona | Gregorio Rábago-Aracil |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | Félix Pérez-Villa María Ángeles Castel, Marta Farrero, Ana García-Álvarez |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo | José Luis Lambert, Beatriz Díaz-Molina, María José Bernardo-Rodríguez |

| Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón (infantile), Madrid | Manuela Camino, Constancio Medrano |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | Iris Garrido-Bravo, Domingo Pascual-Figal, Francisco Pastor-Pérez |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Teresa Blasco-Peiró, Ana Portoles-Ocampo, Marisa Sanz-Julve, Carmen Aured-Guallar |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Luis de La Fuente-Galán, Luis Varela-Falcón, Ana María Correa-Fernández |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | Luis García-Guereta, Carlos Labrandero-de Lera, Viviana Arreo-del Val, Álvaro González-Rocafort, Luz Polo López |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Dimpna C. Albert-Brotons, Ferrán Gran-Ipiña, Raúl Abella |