This report updates the annual data of the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry with the procedures performed in 2021.

MethodsWe describe the clinical profile, therapeutic characteristics and outcomes in terms of survival of the procedures performed in 2021. Their temporal trends are updated for the 2012 to 2020 period.

ResultsIn 2021, 302 heart transplants were performed (8.6% increase versus 2020). The tendency in 2021 confirmed that of prior years, with fewer urgent transplants and a preference for the use of ventricular assist devices. The remaining characteristics and survival showed a clear trend toward stability in the last decade. Compared with 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (2020 and 2021) did not affect short- or long-term survival.

ConclusionsIn 2021, transplant activity returned to prepandemic levels. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic did not significantly affect transplant outcomes. The main transplant features and outcomes have clearly stabilized in the last decade.

Keywords

The characteristics and outcomes of heart transplants in Spain have been analyzed every year for more than 30 years by the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry. The results have become an invaluable viewpoint for assessing the changes over time in Spanish transplant activity. This asset has been particularly valuable in such extraordinary circumstances as those of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

As has been standard since 1991, the present article provides up-to-date information on the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry through the inclusion of the procedures performed in 2021 and updates the temporal data concerning the history of the registry, particularly regarding the last 10 years.

METHODSPatients and proceduresThe procedures of the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry have been detailed in previous reports.1,2 Briefly, the most important clinical procedural data, as well as those of outcomes, mainly in terms of survival, are electronically updated each year using an established datasheet, under the supervision of a contract research organization that is in charge of database maintenance and statistical analysis.

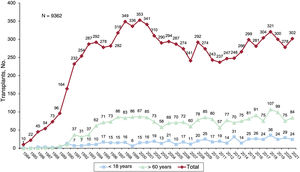

For the last 2 years, 19 centers have undertaken transplant activity (table 1), with 2 centers performing pediatric transplants only. Another 4 centers perform both pediatric and adult transplants while 2 centers perform cardiopulmonary transplants. The types of transplants performed in 2021 and in the entire series are summarized in table 2. Overall, the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry has recorded 9362 procedures. In 2021, 302 transplants were performed, 24 (7.9%) in recipients younger than 18 years and 84 (27.8%) in recipients older than 60 years (figure 1). The data corresponding to the transplants performed in 2021 are provided, as well as those from the previous decade stratified by 3-year period (2012-2014, 2015-2017, and 2018-2020). The percentage of urgent transplants, type of pretransplant circulatory support, and donor age in the last decade were analyzed by year.

Centers participating in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry from 1984 to 2021 (by order of first transplant performed)

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona |

| 2. | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra |

| 3. | Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid (adult, cardiopulmonary) |

| 4. | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba (adult and pediatric) |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia (adult and pediatric, cardiopulmonary) |

| 7. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adult and pediatric) |

| 8. | Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (1989-1994) |

| 9. | Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla |

| 10. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid |

| 11. | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña (adult and pediatric) |

| 12. | Hospital de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona |

| 13. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid (pediatric) |

| 14. | Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias |

| 15. | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona |

| 16. | Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia |

| 17. | Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza |

| 18. | Hospital Clínico, Valladolid |

| 19. | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona (pediatric) |

| 20. | Hospital de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (1984-2021). Type of procedure

| Procedure | 2021 | 1984-2021 |

|---|---|---|

| De novo heart transplant | 288 | 8966 |

| Heart retransplant alone | 5 | 209 |

| Combined heart retransplant | 0 | 7* |

| Combined de novo heart transplant | 9 | 180 |

| Heart-lung | 4 | 89 |

| Heart-kidney | 2 | 76 |

| Heart-liver | 3 | 15 |

| Total | 302 | 9362 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation while categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Differences among time periods were analyzed using a nonparametric test for temporal trends (Kendall τ) for categorical variables and a Wilcoxon-type test for trends for continuous variables.3 Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator and were compared using a log-rank test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

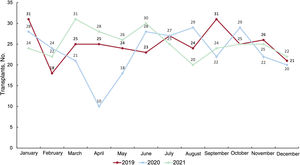

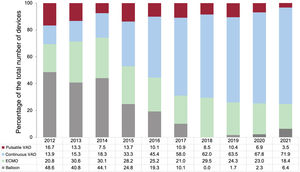

RESULTSRecipient characteristicsIn 2021, 302 transplants were performed, 24 (8.6%) more than in the previous year. Thus, transplant activity returned in 2021 to the levels of 2019, after a fall in the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (figure 2). The main recipient characteristics in 2021 and in the 2012 to 2020 period are summarized in table 3. In the overall population, the mean recipient age was 49.3 years and 29.3% were women, figures similar to those of previous years. In the adult population (age ≥ 18 years at transplant), the mean age since 2012 was 53.3±11.8 years (52.9±11.8 years in 2021) and 25.5% were women (26.2% in 2021). In recent years, the recipient characteristics have largely remained unchanged, except for a significant trend for a larger proportion of recipients with previous cardiac surgery (P < .01), a significant change in the type of pretransplant circulatory support (P < .001), and a nonsignificant tendency for a higher proportion of female recipients (P=.06) (table 3). These tendencies are confirmed by the data from 2021. Although it is possible to detect a tendency in the last 5-year period toward a decrease in urgent transplants (from 50.2% in 2016 to 38.0% in 2021), the difference is not significant (P=.01) (figure 3). In 2021, the data confirm the changes over time detected in the last decade, particularly since 2017, in the type of pretransplant circulatory assist devices being used by patients (figure 4). The use of a balloon pump has become rare and there have been decreases in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and pulsatile ventricular assist devices. In contrast, a considerable increase has been seen in transplanted patients with continuous-flow ventricular assist devices, which represented 71.9% of all circulatory assist devices used in 2021 (figure 4).

Recipient characteristics in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2012-2021)

| Characteristics | 2012-2014(n=761) | 2015-2017(n=884) | 2018-2020(n=899) | P for trend | 2021(n=302) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49.5±16.8 | 49.2±16.7 | 49.2 + 18.2 | .46 | 49.3±17.2 |

| <18 y, % | 7.7 | 8.5 | 9.9 | .54 | 7.6 |

| > 60 y, % | 29.0 | 27.9 | 31.3 | .51 | 27.8 |

| Men, % | 76.2 | 74.3 | 70.2 | .06 | 71.8 |

| BMI | 24.7±4.7 | 24.7±4.7 | 24.7±4.9 | .80 | 24.5±4.8 |

| Underlying etiology, % | .96 | ||||

| Nonischemic dilated | 35.6 | 36.5 | 36.9 | 30.6 | |

| Ischemic | 36.7 | 35.1 | 30.9 | 34.2 | |

| Other | 27.7 | 28.4 | 32.1 | 35.2 | |

| PVR, UW | 2.1±1.2 | 2.2±1.4 | 2.1±1.3 | .22 | 2.0±1.6 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 78.3±35.4 | 80.3±37.2 | 79.7±38.8 | .94 | 81.4±36.9 |

| Bilirubin> 2 mg/dL | 15.7 | 17.2 | 11.5 | .22 | 11.3 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 21.2 | 23.1 | 18.8 | .21 | 21.5 |

| Moderate-severe COPD | 11.3 | 10.2 | 9.7 | .62 | 10.1 |

| Previous infection | 15.1 | 16.1 | 13.0 | .59 | 16.4 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 32.5 | 33.1 | 36.8 | <.001 | 37.1 |

| Type of transplant | .44 | ||||

| Isolated | 96.3 | 96.7 | 96.5 | 95.4 | |

| Heart retransplant | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| Combined | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.0 | |

| Heart-lung | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | |

| Heart-kidney | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | |

| Heart-liver | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 | |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 15.1 | 14.5 | 15.5 | .21 | 10.2 |

| Urgent transplant | 42.0 | 46.9 | 41.5 | .54 | 38.0 |

| Pretransplant circulatory support | <.001 | ||||

| No | 65.2 | 59.6 | 61.6 | 61.6 | |

| Balloon pump | 15.4 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 2.4 | |

| ECMO | 9.6 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 7.0 | |

| Ventricular support | 9.8 | 23.2 | 27.8 | 29.0 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Values are expressed as percentage or mean ± standard deviation.

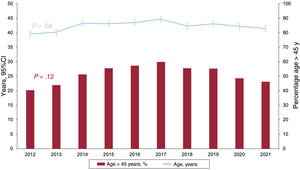

The characteristics of the donors and surgical procedures are summarized in table 4. Donor age has followed a significantly biphasic trend in the last decade, with an increase until 2017 and a decrease thereafter. A similar finding was seen upon analysis of the proportion of donors older than 45 years of age, although the result is not significant (figure 5). As in previous reports, the trends persist for a high percentage of donors who had a preprocedural cardiac arrest and who died of stroke (table 4).

Donor characteristics and procedure times in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2012-2021)

| Characteristic | 2012-2014(n=761) | 2015-2017(n=884) | 2018-2020(n=899) | P for trend | 2021(n=302) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 41.2±14.5 | 43.7±14.6 | 42.5±15.3 | <.001 | 41.5±15.5 |

| > 45 y | 45.6 | 56.7 | 53.2 | <.001 | 46.4 |

| Male sex | 61.8 | 58.7 | 66.6 | .80 | 63.1 |

| Female donor-male recipient | 23.4 | 24.8 | 20.5 | .39 | 18.9 |

| Weight, kg | 73.7±18.2 | 74.6±17.9 | 73.9±20.4 | .48 | 74.9±19.7 |

| Recipient/donor weight | 0.94±0.21 | 0.93±0.19 | 0.93±0.20 | .29 | 0.93±0.18 |

| Recipient/donor weight> 1.2 | 9.5 | 7.5 | 7.7 | .03 | 6.9 |

| Recipient/donor weight <0.8 | 21.7 | 21.8 | 24.9 | .06 | 23.8 |

| Cause of death | <.001 | ||||

| Trauma | 28.2 | 22.2 | 20.6 | 22.6 | |

| Stroke | 60.4 | 62.3 | 65.5 | 62.5 | |

| Other | 11.4 | 15.5 | 13.9 | 14.9 | |

| Pretransplant cardiac arresta | 15.0 | 17.2 | 19.4 | .04 | 19.0 |

| Predonation echocardiogramb | .58 | ||||

| Not performed | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | |

| Normal | 94.9 | 96.3 | 97.3 | 96.0 | |

| Mild generalized dysfunction | 3.0 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 3.6 | |

| Ischemia time | 206.2±65.0 | 195.5±71.6 | 197.0±71.6 | .01 | 197.1±74.8 |

| ≤ 120 min | 10.8 | 17.6 | 16.9 | <.19 | 17.3 |

| 120-180 min | 21.4 | 21.8 | 10.5 | 24.7 | |

| 180-240 min | 40.0 | 34.5 | 37.3 | 32.0 | |

| > 240 min | 27.8 | 26.0 | 25.4 | 26.0 | |

| Bicaval surgical technique | 68.1 | 71.1 | 74.5 | .24 | 74.5 |

The average ischemia time significantly decreased from the 2012 to 2014 period (table 4), largely due to the increase in procedures performed with less than 2hours of ischemia. In 2021, as in the previous 3-year period, 3 out of every 4 transplants were performed with the bicaval technique.

ImmunosuppressionAs shown in table 5, induction immunosuppression has not changed in the last 4 years. Almost all patients were treated with triple therapy, comprising tacrolimus, mycophenolate or mycophenolic acid, and steroids. Almost 80% of patients received anti-CD25 antibody-based induction therapy (mainly basiliximab).

Induction immunosuppression in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2012-2021)

| 2012-2014(n=761) | 2015-2017(n=884) | 2018-2020(n=899) | P for trend | 2021(n=302) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin inhibitors | |||||

| Cyclosporin | 18.1 | 6.8 | 5.2 | <.001 | 0.4 |

| Tacrolimus | 81.9 | 93.2 | 94.8 | <.001 | 99.6 |

| Antiproliferative agents | |||||

| Mycophenolate/mycophenolic acid | 99.7 | 98.8 | 99.3 | .41 | 98.6 |

| Azathioprine | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | .41 | 1.4 |

| mTOR inhibitors | |||||

| Sirolimus | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | .60 | 0.4 |

| Everolimus | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.1 | .99 | 0.4 |

| Steroids | 96.3 | 97.5 | 97.5 | .41 | 97.3 |

| Induction | <.001 | ||||

| No | 12.4 | 16.3 | 18.3 | 14.9 | |

| ALG/ATG | 2.0 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 5.4 | |

| Anti-CD25 | 85.0 | 78.7 | 77.8 | 79.7 | |

| Other | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

ALG, antilymphocyte globulin; anti-CD25, basiliximab, daclizumab; ATG, antithymocyte globulin.

Values are expressed as percentages.

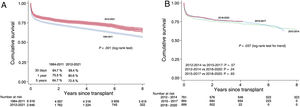

Survival in the 2012 to 2021 period was about 80.6% in the first posttransplant year and more than 72.5% at 5 years, which was significantly better than that recorded in the entire previous series (figure 6A). In the 3-year period from 2018 to 2020, survival was 81.5% in the first year and 76.2% in the third year. Although the 2015 to 2017 and 2018 to 2020 periods seem to show an improvement vs 2012 to 2014, the difference is not statistically significant (figure 6B). The slight differences seen between the curves are limited to the earliest period, with survival of 78.3%, 80.7%, and 81.5% in the first years of the 2012 to 2014, 2015 to 2017, and 2018 to 2020 periods, respectively. Subsequently, the curves are clearly parallel. table 6 summarizes some of the univariable predictors of mortality. The factors most strongly associated with mortality were those related to the pretransplant clinical status of the recipient (need for advanced circulatory support or mechanical ventilation) and to comorbidity (age, pretransplant infection, diabetes or pretransplant renal failure, ischemic etiology).

Univariate analysis of survival by the baseline characteristics of the recipient, donor, and procedure (2012-2021)

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient age | ||

| <18 y | 1 | |

| 18-60 y | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | .12 |

| > 60 y | 1.9 (1.4-2.6) | <.001 |

| Underlying etiology | ||

| Nonischemic dilated | 1 | |

| Ischemic dilated | 1.4 (1.2-1.4) | <.001 |

| Other | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .10 |

| Type of transplant | ||

| Isolated transplant | 1 | |

| Combined transplant | 1.5 (0.9-2.3) | .09 |

| Retransplant | 1.2 (0.7-2.0) | .52 |

| Donor age | ||

| ≤ 45 y | 1 | |

| > 45 y | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | .07 |

| Urgency code | ||

| Elective | 1 | |

| Urgent | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | <.001 |

| Type of support | ||

| No support | 1 | |

| Balloon pump | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | .56 |

| ECMO | 1.7 (1.4-2.2) | <.001 |

| Ventricular support | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 1.5 (1.2-1.7) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 1.9 (1.6-2.4) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant infection | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant diabetes | 1.2 (1.1-1.5) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

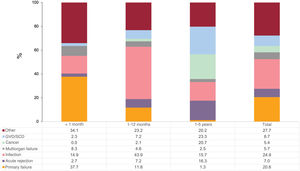

In the first 5 posttransplant years, the most prevalent specific causes of death were infection (24.9%) and primary graft failure (20.6%) (figure 7), which were almost entirely concentrated in the first posttransplant year and in the first posttransplant month, respectively. Acute transplant rejection was an infrequent cause of death, particularly in the first year, although its prevalence was not negligible between the second and fifth posttransplant years (16.3%). Between the second and fifth posttransplant years, the most frequent causes of death were graft vascular disease/sudden cardiac death (23.3%) and cancer (20.7%).

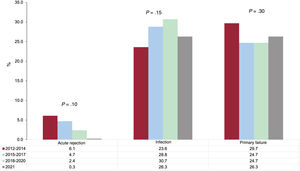

The tendencies in the main causes of death during the first posttransplant year (a period in which follow-up data were available for all patients) were not significant, although there was a numerical tendency for a lower prevalence of acute rejection and a higher prevalence of infections (figure 8).

To assess the possible influence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on outcomes, we analyzed 30- and 60-day survival by week of transplant from 2019, the year immediately preceding the pandemic, in patients who underwent transplant from 2019 to 2021. In addition, we analyzed the mortality rate during the above period in patients undergoing transplant before 2019 (table 7). Deaths due to a viral infection other than cytomegalovirus or hepatitis (which are the 2 viral causes specifically considered in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry) increased from 4 in 2019 to 28 and 27 in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

Survival of patients undergoing transplant during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (2020-2021) vs the previous year (2019) and mortality during the same period in patients undergoing transplant before 2019

| Transplanted in 2019-2021 | |||

| Transplant period | Mortality | ||

| Year | 6-month period | 30-day mortality, % | 60-day mortality, % |

| 2019 | First half of year | 13.1 | 16.5 |

| Second half of year | 11.1 | 14.4 | |

| 2020 | First half of year | 10.1 | 14.0 |

| Second half of year | 8.1 | 12.8 | |

| 2021 | First half of year | 5.6 | 8.7 |

| Second half of year | 5.2 | 8.3 | |

| Transplanted before 2019 | |||

| Period in which death occurred | |||

| Year | 6-month period | Total mortality, % | |

| 2019 | First half of year | 2.7 | |

| Second half of year | 2.3 | ||

| 2020 | First half of year | 2.5 | |

| Second half of year | 2.6 | ||

| 2021 | First half of year | 2.6 | |

| Second half of year | 2.5 | ||

The first finding that can be highlighted in the present report is that heart transplant activity in Spain recovered in 2021 vs the previous year and returned to levels similar to those of the prepandemic years. Although transplant recipients are more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection and exhibit higher associated mortality than the general population,4 the pandemic does not appear to have had a notable influence on our outcomes in terms of overall survival. Mortality in the earliest posttransplant phase was unaffected in 2020 and 2021 vs 2019, the year immediately preceding the pandemic. Equally, among patients in the historic series who underwent transplant before 2019, the mortality rates during the pandemic years did not differ from those of 2019, at about 2.5%. However, there was an increase in the number of deaths due to viral infections not typically linked to transplants. The total number of deaths, although higher than in 2019, was probably too small to show a measurable impact on total mortality. Another possible explanation is the impact of competing risks, with SARS-CoV-2 mortality concentrated in particularly vulnerable patients with a poor vital prognosis independently of infection. Taking into account all of the data, the Spanish heart transplant system has shown a maturity that has enabled it to easily overcome, in terms of activity and outcomes, the negative effects of a pandemic with such far-reaching consequences.

The transplant system has shown maturity not only in its resistance to the effects of the pandemic, but also in its stability in recent years in terms of both outcomes and the characteristics of the recipients, donors, and procedures. The most striking result from the last 3 years is the decrease in urgent transplants, an undoubted result of the change in the inclusion criteria for the waiting list that was implemented in July 2017. In accordance with this milestone, and related to patient inclusion, we also found widespread use of short-term ventricular assist devices vs ECMO and balloon pumps, with the latter barely used. A consequence of this new paradigm is the progressive increase in patients with pretransplant sternotomy because this technique is required for the implantation of most of the devices used. Otherwise, the use of donors who could be considered suboptimal appears to have stabilized, such as due to oversizing vs the recipient, cold ischemia times largely less than 4hours, and use of the bicaval technique. The same can be applied to immunosuppression, based on triple therapy comprising tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids and highly frequent induction with basiliximab.

Probably in relation to this standardization of the procedure, we found, for the first time in many years,5 that there were no significant differences in survival among the 3-year periods from the last decade. Previously, the improvements were always related to the earliest mortality (first year). In our current clinical context, we have probably reached maximum possible survival, which is slightly higher than 80% in the first year. However, there may still be room for improvement related to the accumulation of experience for the groups most recently adopting ventricular support programs or the expansion of donation after circulatory death.6

CONCLUSIONSHeart transplant activity in Spain has returned to prepandemic levels. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has not negatively affected survival, which has remained stable in the last decade.

FUNDINGThis work has not received NY funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors have contributed to the data collection, have critically revised the manuscript, and have approved its publication in the current form. F. González-Vílchez drafted the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

Collaborators in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry 1984 to 2021

| Center | Collaborators |

|---|---|

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria | Manuel Cobo-Belaustegui, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, José Antonio Vázquez de Prada, Francisco Nistal-Herrera, Cristina Castrillo |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias | Beatriz Díaz-Molina, Vanesa Alonso Fernández, Cristina Fidalgo-Muñiz |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | Antonio Grande-Trillo, Diego Rangel-Sousa |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Sonia Mirabet, Laura López, Isabel Zegrí |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | María Ángeles Castel, Marta Farrero Torres |

| Hospital Universitari Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | Carles Díez-López, José González-Costello, Nicolás Manito |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adults) | Carlos Ortiz, Adolfo Villa, Iago Sousa, Javier Castrodeza, María Jesús Valero, Eduardo Zataraín, Paula Navas, Miriam Juárez, Manuel Martínez-Sellés |

| Hospital Univesitari i Politècnic La Fe, Valencia | Raquel López, Víctor Donoso, Soledad Martínez, Ignacio Sánchez Lázaro, Luis Martínez |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Amador López-Granados |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid | Javier Segovia Cubero, Francisco Hernandez Pérez, Cristina Mitroi, Mercedes Rivas Lasarte, Sara Lozano Jiménez, José María Viéitez Flórez |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | María Dolores García-Cosío, Laura Morán-Fernández, Juan Carlos López-Azor, Irene Marco-Clement |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, A Coruña | José Joaquin Cuenca-Castillo, María Jesús Paniagua-Martín, Eduardo Barge-Caballero, Gonzalo Barge-Caballero, David Couto-Mallón, Víctor Mosquera-Rodríguez |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | Luis García-Guereta Silva, Álvaro González-Rocafort, Carlos Labrandero de Lera |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (pediatric) | Manuela Camino-López, Nuria Gil-Villanueva |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Luis de la Fuente-Galán, Javier Tobar-Ruiz |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | Iris P. Garrido-Bravo, Francisco J. Pastor-Pérez, Domingo A. Pascual-Figal |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Teresa Blasco-Peiró, Ana Pórtoles-Ocampo, María Lasala-Alastuey |

| Clínica Universitaria, Pamplona | Gregorio Rábago-Juan-Aracil, Rebeca Manrique-Antón, Leticia Jimeno-San Martín |

| Hospital Universitario Doctor Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Antonio García-Quintana, María del Val Groba-Marco, Mario Galván-Ruiz |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Ferrán Gran-Ipiña |