Our aim was to describe the characteristics and outcomes of heart transplants in Spain.

MethodsWe analyzed trends in recipient and donor characteristics, recipient-donor interaction, surgical procedures, immunosuppression, and outcomes of patients included in the Spanish heart transplant registry from 2014 to 2023. Changes in survival were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

ResultsIn 2023, 325 cardiac transplants were performed (4.5% more than in the previous year), with a total of 2987 procedures from 2014 to 2023. There was a trend toward performing more transplants in women (29.2%), with etiologies other than cardiomyopathy (32.6%), and with better pretransplant status (less hepatic [12.5%], renal [glomerular filtration rate, 81.5mL/min/1.73 m2], and respiratory [8.7%] involvement). In 2023, the number of urgent transplants increased (44% of the total), especially those performed after circulatory support with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (36% of total assistance), and transplants performed with donation after circulatory death (17.9%). Survival improved in the triennium from 2020 to 2022 compared with 2014 to 2016 (83.0% at 1 year from 2020-2022 vs 79.0% from 2014-2016).

ConclusionsThe number of transplants performed in Spain showed an upward trend, with recipients with better clinical status and an increasing use of donation after circulatory death. Survival improved in the last triennium.

Keywords

In 2024, a milestone was reached in the history of heart transplantation in Spain, with the 40th anniversary of the first transplant. In addition, 2024 marks the 33rd anniversary of the publication of the first annual report of the Spanish heart transplant registry.1 In the intervening years, there have been multiple changes in numerousfields. The latest advances now adopted are ABO-incompatible heart transplants and transplants using grafts from donation after circulatory death, alongside the more traditional donation after brain death. The present report includes information on the procedures performed in 2023 and updates the historic series, particularly focusing on mortality data. As customary, the main findings are concentrated on procedures performed in the last 10 years (2014-2023).

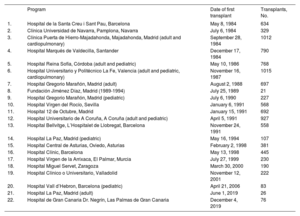

METHODSPatients and proceduresThe Spanish heart transplant registry is a voluntary registry of heart transplant procedures performed in Spain. Although voluntary, the registry encompasses all procedures conducted in all centers with transplant activity in Spain since 1984 (table 1). The registry includes variables related to the demographic and clinical characteristics of recipients, donors, surgical procedures, immunosuppression protocols, and posttransplant complications, including mortality and its causes. The registry has been continually active for more than 30 years. The main changes in its structure are related to, first, the adoption of electronic data submission, second, the addition or change of variable definition or coding, and, finally, the incorporation of centers initiating transplant activity. Structurally, the Spanish heart transplant registry consists of a management team including a medical director and an assessment committee that is in charge of evaluating and approving the suitability of the use of registry data for research purposes and of an external contract research organization that is responsible for database maintenance and statistical analysis, activities that also involve comparisons with other international registries.

Programs participating in the Spanish heart transplant registry from 1984 to 2023 (by order of first transplant performed)

| Program | Date of first transplant | Transplants, No. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | May 8, 1984 | 634 |

| 2. | Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra | July 6, 1984 | 329 |

| 3. | Clínica Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid (adult and cardiopulmonary) | September 28, 1984 | 1012 |

| 4. | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander | December 17, 1984 | 790 |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba (adult and pediatric) | May 10, 1986 | 768 |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia (adult and pediatric, cardiopulmonary) | November 16, 1987 | 1015 |

| 7. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adult) | August 2, 1988 | 697 |

| 8. | Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (1989-1994) | July 25, 1989 | 21 |

| 9. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (pediatric) | July 6, 1990 | 227 |

| 10. | Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | January 6, 1991 | 568 |

| 11. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid | January 15, 1991 | 692 |

| 12. | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña (adult and pediatric) | April 5, 1991 | 927 |

| 13. | Hospital Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | November 24, 1991 | 558 |

| 14. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid (pediatric) | May 16, 1994 | 107 |

| 15. | Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias | February 2, 1998 | 381 |

| 16. | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona | May 13, 1998 | 445 |

| 17. | Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | July 27, 1999 | 230 |

| 18. | Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | March 30, 2000 | 190 |

| 19. | Hospital Clínico o Universitario, Valladolid | November 12, 2001 | 222 |

| 20. | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona (pediatric) | April 21, 2006 | 83 |

| 21. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid (adult) | June 1, 2019 | 26 |

| 22. | Hospital de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | December 4, 2019 | 76 |

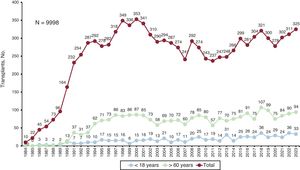

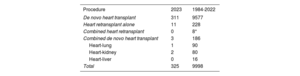

The total numbers and types of transplant conducted in 2023 and in the entire series are summarized in table 2. In 2023, 325 transplants were performed; most (n=311) were isolated heart transplants. There were 11 retransplants (3.4%) and 3 combined transplants (2 heart-kidney transplants and 1 heart-lung transplant). In terms of age, 10.2% of recipients (33 patients) were younger than 18 years and 28.9% (94 patients) were older than 60 years. Since the beginning, the Spanish heart transplant registry has recorded 9998 procedures (figure 1). The present report updates the information with the introduction of data related to the transplants performed in 2023. In addition, we analyzed the changes over time in the characteristics and outcomes of the procedures in the previous decade (since 2014). To do so, the period was stratified into triennia (2014-2016, 2017-2019, and 2020-2022). Some variables were analyzed on an annual basis (urgent transplants, circulatory assist devices).

Spanish heart transplant registry (1984-2023). Type of procedure

| Procedure | 2023 | 1984-2022 |

|---|---|---|

| De novo heart transplant | 311 | 9577 |

| Heart retransplant alone | 11 | 228 |

| Combined heart retransplant | 0 | 8* |

| Combined de novo heart transplant | 3 | 186 |

| Heart-lung | 1 | 90 |

| Heart-kidney | 2 | 80 |

| Heart-liver | 0 | 16 |

| Total | 325 | 9998 |

Continuous quantitative variables are presented as mean±standard deviation, while categorical variables are expressed as percentages. The nonparametric Kendall tau test and the Wilcoxon test for trends were used to assess temporal trends in the categorical and quantitative variables, respectively.2 Cumulative survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between groups were determined using the log-rank test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a 2-tailed P<.05.

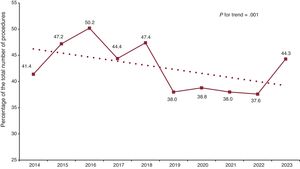

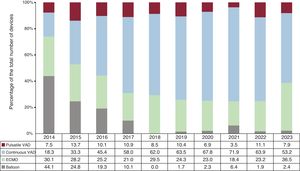

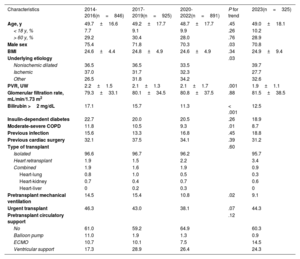

RESULTSRecipient characteristicsIn total, 325 transplants were performed in 2023, marking a 4.5% increase compared with the previous year (figure 1). The principal recipient characteristics in 2023 and from 2014 to 2023 are summarized in table 3. The main changes in the last decade include the relative increase in female recipients, who represented 30% of all recipients in 2023. Related to this tendency is the percentage decrease in ischemic etiology as the leading cause of the heart disease prompting the transplant and the increase in other etiologies that are percentually more frequent in women than in men (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 12.6% in women vs 6.1% in men; restrictive cardiomyopathy, 8.4% vs 4.1%; and congenital heart disease, 11.1% vs 5.7%). As in the previous report,3 a trend was seen toward recipients with better clinical status. This was inferred from a significant trend for fewer recipients with elevated pretransplant bilirubin levels (as an indicator of better congestive status and lower ischemic kidney disease) and for the need for pretransplant intubation, which was required in less than 10% of patients in 2023. In addition, the previous tendency toward a decrease in urgent transplants was broken in 2023, with an uptick to 44% in 2023 (P for trend=.02) (figure 2). As in previous years, there was widespread use of pretransplant circulatory support in 2023 (191 recipients [39.7%]). Since 2014, 1815 patients (38.5%) have undergone transplantation with previous circulatory support. However, the most relevant finding in 2023 was the relative increase in the pretransplant use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (from 23.2% in 2022 to 36.5% in 2023) at the expense of ventricular assist devices (from 75.0% in 2022 to 61.1% in 2023) (figure 3).

Recipient characteristics in the Spanish heart transplant registry (2014-2023)

| Characteristics | 2014-2016(n=846) | 2017-2019(n=925) | 2020-2022(n=891) | P for trend | 2023(n=325) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49.7±16.6 | 49.2±17.7 | 48.7±17.7 | .45 | 49.0±18.1 |

| < 18 y, % | 7.7 | 9.1 | 9.9 | .26 | 10.2 |

| > 60 y, % | 29.2 | 30.4 | 28.0 | .76 | 28.9 |

| Male sex | 75.4 | 71.8 | 70.3 | .03 | 70.8 |

| BMI | 24.6±4.4 | 24.8±4.9 | 24.6±4.9 | .34 | 24.9±9.4 |

| Underlying etiology | .03 | ||||

| Nonischemic dilated | 36.5 | 36.5 | 33.5 | 39.7 | |

| Ischemic | 37.0 | 31.7 | 32.3 | 27.7 | |

| Other | 26.5 | 31.8 | 34.2 | 32.6 | |

| PVR, UW | 2.2±1.5 | 2.1±1.3 | 2.1±1.7 | .001 | 1.9±1.1 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 79.3±33.1 | 80.1±34.5 | 80.8±37.5 | .88 | 81.5±38.5 |

| Bilirubin >2 mg/dL | 17.1 | 15.7 | 11.3 | < .001 | 12.5 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 22.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 | .26 | 18.9 |

| Moderate-severe COPD | 11.8 | 10.5 | 9.3 | .01 | 8.7 |

| Previous infection | 15.6 | 13.3 | 16.8 | .45 | 18.8 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 32.1 | 37.5 | 34.1 | .39 | 31.2 |

| Type of transplant | .60 | ||||

| Isolated | 96.6 | 96.7 | 96.2 | 95.7 | |

| Heart retransplant | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 3.4 | |

| Combined | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.9 | |

| Heart-lung | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| Heart-kidney | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| Heart-liver | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 14.5 | 15.4 | 10.8 | .02 | 9.1 |

| Urgent transplant | 46.3 | 43.0 | 38.1 | .07 | 44.3 |

| Pretransplant circulatory support | .12 | ||||

| No | 61.0 | 59.2 | 64.9 | 60.3 | |

| Balloon pump | 11.0 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | |

| ECMO | 10.7 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 14.5 | |

| Ventricular support | 17.3 | 28.9 | 26.4 | 24.3 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenator; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

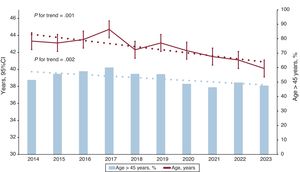

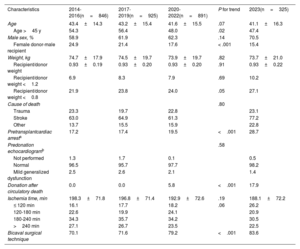

Donor and surgical procedure characteristics are summarized in table 4. There was a significant trend toward a lower use of suboptimal donors, defined as those older than 45 years, which fell to 47.4% of all transplants in 2023 vs 54.3% from 2014 to 2016 (figure 4). The trend for transplants with a recipient-donor sex mismatch (male recipient-female donor) was also significant, falling from 24.9% in the triennium from 2014 to 2016 to 15.4% in 2023.

Donor characteristics and procedure times in the Spanish heart transplant registry (2014-2023)

| Characteristics | 2014-2016(n=846) | 2017-2019(n=925) | 2020-2022(n=891) | P for trend | 2023(n=325) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.4±14.3 | 43.2±15.4 | 41.6±15.5 | .07 | 41.1±16.3 |

| Age >45 y | 54.3 | 56.4 | 48.0 | .02 | 47.4 |

| Male sex, % | 58.9 | 61.9 | 62.3 | .14 | 70.5 |

| Female donor-male recipient | 24.9 | 21.4 | 17.6 | < .001 | 15.4 |

| Weight, kg | 74.7±17.9 | 74.5±19.7 | 73.9±19.7 | .82 | 73.7±21.0 |

| Recipient/donor weight | 0.93±0.19 | 0.93±0.20 | 0.93±0.20 | .91 | 0.93±0.22 |

| Recipient/donor weight <1.2 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 7.9 | .69 | 10.2 |

| Recipient/donor weight <0.8 | 21.9 | 23.8 | 24.0 | .05 | 27.1 |

| Cause of death | .80 | ||||

| Trauma | 23.3 | 19.7 | 22.8 | 23.1 | |

| Stroke | 63.0 | 64.9 | 61.3 | 77.2 | |

| Other | 13.7 | 15.5 | 15.9 | 22.8 | |

| Pretransplantcardiac arresta | 17.2 | 17.4 | 19.5 | <.001 | 28.7 |

| Predonation echocardiogramb | .58 | ||||

| Not performed | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| Normal | 96.5 | 95.7 | 97.7 | 98.2 | |

| Mild generalized dysfunction | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.4 | |

| Donation after circulatory death | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.8 | <.001 | 17.9 |

| Ischemia time, min | 198.3±71.8 | 196.8±71.4 | 192.9±72.6 | .19 | 188.1±72.2 |

| ≤ 120 min | 16.1 | 17.7 | 18.2 | .06 | 26.2 |

| 120-180 min | 22.6 | 19.9 | 24.1 | 20.9 | |

| 180-240 min | 34.3 | 35.7 | 34.2 | 30.5 | |

| >240 min | 27.1 | 26.7 | 23.5 | 22.5 | |

| Bicaval surgical technique | 70.1 | 71.6 | 79.2 | <.001 | 83.6 |

The most significant data regarding the donation process, consolidated in 2023, concerned donation after circulatory death (asystole). The first such procedure was conducted in January 2020 in Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda. By December 2023, a total of 110 such transplants had been performed in 14 programs, 98 in adult recipients and 12 in pediatric patients. In 2023, transplants with donation after circulatory death comprised almost 18% of all procedures and 24% of all transplants performed at centers with an active circulatory death donation program. In addition, in 2023, 3 ABO-incompatible transplants were performed, a technique restricted to pediatric recipients. Since the initiation of these programs in 2018, this technique has represented 13.4% of all procedures performed in accredited centers.

Regarding the remaining characteristics, the last decade showed a highly significant trend toward ensuring recipient-donor sex concordance to avoid the unfavorable matching of a female donor with a male recipient (15.4% of patients in 2023 vs 24.9% in the triennium from 2014 to 2016). Equally, the use of the bicaval technique increased to almost 84% of all procedures. Although the difference was not statistically significant, ischemia time showed a slight tendency toward a decrease, with an average of slightly longer than 3hours in 2023.

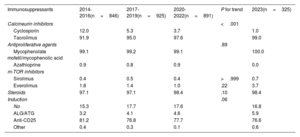

ImmunosuppressionInduction immunosuppression trends are summarized in table 5. Over the past decade, there have been no significant new developments. Except in rare situations, patients receive triple therapy consisting of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil/mycophenolic acid, and steroids. Induction therapy, often involves the use of antibodies (82.5% of patients), generally basiliximab.

Induction immunosuppression in the Spanish heart transplant registry (2014-2023)

| Immunosuppressants | 2014-2016(n=846) | 2017-2019(n=925) | 2020-2022(n=891) | P for trend | 2023(n=325) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin inhibitors | <.001 | ||||

| Cyclosporin | 12.0 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 1.0 | |

| Tacrolimus | 91.9 | 95.0 | 97.6 | 99.0 | |

| Antiproliferative agents | .89 | ||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil/mycophenolic acid | 99.1 | 99.2 | 99.1 | 100.0 | |

| Azathioprine | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | |

| m-TOR inhibitors | |||||

| Sirolimus | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | >.999 | 0.7 |

| Everolimus | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | .22 | 3.7 |

| Steroids | 97.1 | 97.1 | 98.4 | .10 | 98.4 |

| Induction | .06 | ||||

| No | 15.3 | 17.7 | 17.6 | 16.8 | |

| ALG/ATG | 3.2 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 5.9 | |

| Anti-CD25 | 81.2 | 76.8 | 77.7 | 76.6 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

ALG, antilymphocyte globulin; anti-CD25, basiliximab, daclizumab; ATG, antithymocyte globulin.

Values express percentages.

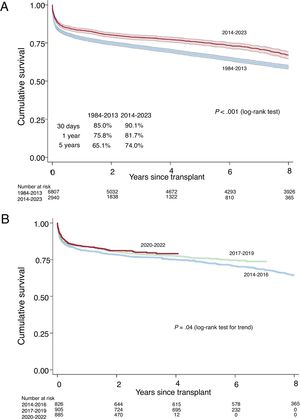

From 2014 to 2023, survival was 81.4% in the first posttransplant year and 74.0% at 5 years, which was significantly better than in the 1984 to 2013 period (figure 5A). In the pediatric population (recipients younger than 18 years at transplant), posttransplant survivals at 1 and 5 years were 83.6% and 80.4%, respectively, in the last decade.

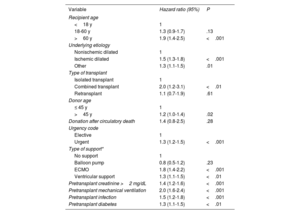

The trend for improved survival in recent years was statistically significant (figure 5B). Survival in the first posttransplant year increased from 79.0% in the triennium from 2014 to 2016 to 83.0% from 2020 to 2022. Some of the univariable predictors of mortality are summarized in table 6. As already noted in the previous report,3 the main factors associated with mortality were related to clinical characteristics or variables associated with the recipient's pretransplant clinical status.

Univariable analysis of survival by baseline characteristics of the recipient, donor, and procedure (2014-2023)

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95%) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient age | ||

| <18 y | 1 | |

| 18-60 y | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | .13 |

| >60 y | 1.9 (1.4-2.5) | <.001 |

| Underlying etiology | ||

| Nonischemic dilated | 1 | |

| Ischemic dilated | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | <.001 |

| Other | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | .01 |

| Type of transplant | ||

| Isolated transplant | 1 | |

| Combined transplant | 2.0 (1.2-3.1) | <.01 |

| Retransplant | 1.1 (0.7-1.9) | .61 |

| Donor age | ||

| ≤ 45 y | 1 | |

| >45 y | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .02 |

| Donation after circulatory death | 1.4 (0.8-2.5) | .28 |

| Urgency code | ||

| Elective | 1 | |

| Urgent | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) | <.001 |

| Type of support* | ||

| No support | 1 | |

| Balloon pump | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | .23 |

| ECMO | 1.8 (1.4-2.2) | <.001 |

| Ventricular support | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | <.01 |

| Pretransplant creatinine >2 mg/dL | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 2.0 (1.6-2.4) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant infection | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant diabetes | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | <.01 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

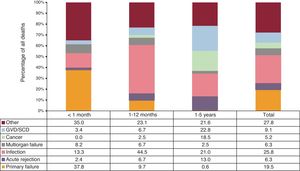

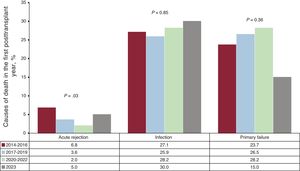

The specific causes of death in the first 5 posttransplant years remained infection (25.8%) and primary graft failure (19.5%) (figure 6). As expected, primary graft failure was the leading cause of death in the first posttransplant month (37.8% of all deaths). Infection was by the far the leading cause of death after the first month and until the 1-year posttransplant point (44.5% of deaths), although the risk subsequently remained high (21% of deaths until the fifth posttransplant year). Acute rejection was a nonnegligible cause of death, particularly in the period between 1 and 5 posttransplant years (13% of deaths). Even so, in this period, the most frequent causes of death were graft vascular disease/sudden cardiac death (22.8%), infection (21%), and cancer (18.5%). Primary graft failure (14.6%) and particularly infection (25.0%) were also the most frequent causes of death in the first 5 posttransplant years in the pediatric population.

To assess changes in the main causes of death over time, we studied the same causes in the first posttransplant year to ensure a comparable follow-up among triennia. Acute rejection significantly decreased as a cause of death during the last decade. In contrast, primary graft failure and infection remained statistically stable in the same period (figure 7).

DISCUSSIONThe results of the Spanish heart transplant registry updated to 2023 can be summarized in the following points. Firstly, certain trends identified in the previous report3 have become consulated. For instance, there has been a renewed increase in the number of procedures, although it remains uncertain whether this correlates with the rise in donation after circulatory death. Similarly, there was an increase in the proportion of female recipients. As can be seen in previous studies, this increase was actually due to the absolute decrease in male recipients in the last 20 years.4 This proportional increase also explains the uptick in atypical underlying heart disease etiologies, which are generally more prevalent in women. Finally, recipients’ pretransplant clinical status has progressively improved, which is in line with the use of more advanced circulatory support systems and a refinement of recipient selection processes.

Second, there was a notable increase in urgent transplants, reversing the downward trend observed in previous years. This finding is undoubtedly related to the shift in the use of different types of circulatory support, with an increase in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation vs ventricular assist devices. The revisions in the urgency criteria5 by the Spanish National Transplant Organization (NTO), based on the recommendations from transplant centers, are certainly responsible for these findings, even though they came into force well into 2023.

Third, a tendency was detected for more favorable donor characteristics, as evidenced by the fall in the percentage of suboptimal donors. In addition, there was a decrease in transplants with known unfavorable recipient-donor interactions, such as those due to sex discordance (male recipient-female donor).

Fourth, there was a progressive increase in donation after circulatory death, as well as in donation characteristics that are particularly well-managed in this setting.

Fifth, the results showed significantly improved survival in the last triennium (2020-2022) vs the first triennium of the decade, in contrast to the stabilization in survival data described in the previous report.3 Although the cause of this improvement would require a more detailed analysis that is beyond the scope of the present report, it is highly likely that a combination of the tendencies shown in previous reports would robustly explain these findings.

LimitationsThis study has the limitations inherent to a registry of unaudited procedures.

CONCLUSIONSThe data from recent years have confirmed a tendency toward an increase in the number of transplants, which is highly likely to be related to the uptick in donation after circulatory death. The slight improvement in survival outcomes probably reflects better recipient selection and pretransplant management and a refined acceptance process for donors.

FUNDINGThis work has not received any funding.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONSThe present registry was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario La Fe and was conducted with the recipients’ informed consent. The report considers donor and recipient sex to be possible predictive variables, as indicted in the descriptive tables of the manuscript.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCENo artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSF. González-Vílchez drafted the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the data collection, have critically revised the manuscript, and have approved its publication in the current form.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

| Center | Collaborators |

|---|---|

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria | Manuel Cobo-Bealustegui, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, José Antonio Vázquez de Prada, Francisco Nistal-Herrera, Cristina Castrillo |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias | Beatriz Díaz-Molina, Vanesa Alonso-Fernández, Cristina Fidalgo-Muñiz |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | Antonio Grande-Trillo, Diego Rangel-Sousa |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Marta De Antonio-Ferrer, Laura López |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | Marta Farrero-Torres, Ángeles Castells, Pedro Caravaca, Eduard Solé |

| Hospital Universitari Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | José González-Costello, Elena García-Romero, Carles Díez-López, Fabrizio Sbraga, Pablo Catalá-Ruiz, Lorena Herrador |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adults) | Zorba Blázquez, Iago Sousa, Javier Castrodeza, Eduardo Zataraín, Adolfo Villa, Carlos Ortiz-Bautista, Manuel Martínez-Sellés |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (pediatric) | Manuela Camino-López, Nuria Gil-Villanueva, Juan Miguel Gil-Jaurena |

| Hospital Univesitari i Politècnic La Fe, Valencia | Raquel López-Viella, Víctor Donoso-Trenado, Soledad Martínez-Penadés, Ignacio Sánchez-Lázaro |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Francisco Carrasco-Ávalos |

| Hospital Universitario Clínica Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid | Manuel Gómez-Bueno, Javier Segovia-Cubero, Cristina Mitroi, Mercedes Rivas-Lasarte, Sara Lozano-Jiménez, Jose María Vieitez-Flórez |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | María Dolores García-Cosío, Laura Morán-Fernández, Javier González Martín, Irene Marco-Clement |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, A Coruña | Maria Jesús Paniagua-Martín, Eduardo Barge-Caballero, Gonzalo Barge-Caballero, David Couto-Mallón, Daniel Enríquez-Vázquez |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid (pediatric) | Luis García-Guereta Silva, Álvaro González-Rocafort, Carlos Labrandero de Lera |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid (adults) | Inés Ponz de Antonio, Adriana Rodríguez-Chaverri |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Luis de la Fuente-Galán, Javier Tobar-Ruiz |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | Iris P. Garrido-Bravo, Francisco J. Pastor-Pérez, Domingo A. Pascual-Figal |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Teresa Blasco-Peiró, Ana Pórtoles-Ocampo, Ana Marcén-Mirabete |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona | Gregorio Rábago-Juan-Aracil, Rebeca Manrique-Antón, Leticia Jimeno-San Martín |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Antonio García-Quintana, María del Val Groba-Marco, Mario Galván-Ruiz, Miguel Fernández de Sanmamed-Girón |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Ferrán Gran-Ipiña, Paola Dolader |