The present article reports the characteristics and results of heart transplantation in Spain since this therapeutic modality was first used in May 1984.

MethodsWe summarize the main features of recipients, donors, and surgical procedures, as well as the results of all heart transplantations performed in Spain until December 31, 2012.

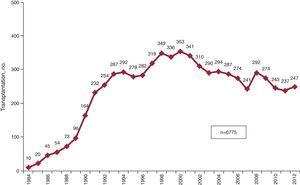

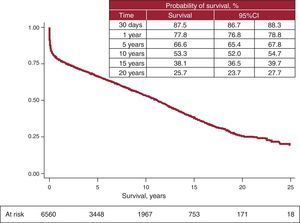

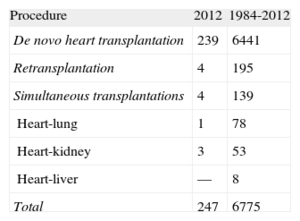

ResultsA total of 247 heart transplantations were performed in 2012. The whole series consisted of 6775 procedures. Recent years have seen a progressive worsening in the clinical characteristics of recipients (34% aged over 60 years, 22% with severe kidney failure, 17% with insulin-dependent diabetes, 29% with previous heart surgery, 16% under mechanical ventilation) and donors (38% aged over 45 years, 26% with recipient: donor weight mismatch>20%), and in surgical conditions (29% of procedures at >4 h ischemia and 36% as emergency transplantations). The probability of survival at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years of follow-up was 78%, 67%, 53%, and 38%, respectively. These results have remained stable since 1995.

ConclusionsIn recent years, the number of heart transplantations/year in Spain has remained stable at around 250. Despite the worsening of recipient and donor clinical characteristics and of time-to-surgery, the results in terms of mortality have remained stable and compare favorably with those of other countries.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONSince 1991, the Spanish Heart Transplantation Registry (Registro Español de Trasplante Cardiaco [RETC]) has published a description of the clinical and surgical characteristics and general results of heart transplantation procedures performed in Spain (Appendix).1–23 The present article describes these data and includes patients undergoing transplantation prior to December 31, 2012. The major strengths of the RETC lie in its inclusion of practically all heart transplantation procedures in hospitals throughout Spain since May 1984, independently of their characteristics and outcomes. Moreover, data are collected prospectively and are recorded in a single database, following criteria unanimously agreed on by all heart transplantation teams.

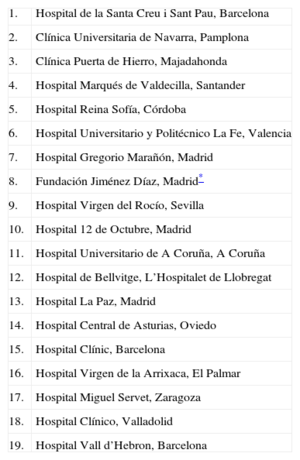

METHODSPatients and CentersOf the 19 centers providing the RETC with data, 18 are currently active (Table 1). The numbers of procedures per year are shown in Figure 1. Importantly, in the whole time series, the RETC has no data on 14 patients and consequently the present study included a total of 6761 patients. Procedure types for 2012 and the whole time series are given in Table 2.

Centers Participating in the Spanish Heart Transplantation Registry (1984-2012) (in Chronological Order of First Transplantation Procedures)

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona |

| 2. | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona |

| 3. | Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda |

| 4. | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia |

| 7. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid |

| 8. | Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid* |

| 9. | Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla |

| 10. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid |

| 11. | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña |

| 12. | Hospital de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat |

| 13. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid |

| 14. | Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo |

| 15. | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona |

| 16. | Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar |

| 17. | Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza |

| 18. | Hospital Clínico, Valladolid |

| 19. | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona |

The database consists of 175 pre-established clinical variables, unanimously agreed on by all teams collecting data on recipients, donors, surgical techniques, immunosuppression, and follow-up. In 2012, the major innovation was the introduction of a web-based tool that enables groups to enter and update data directly online. The database support is a Microsoft Excel file. This replaced the earlier data-collection method that involved each center sending data to the registry director by e-mail in Microsoft Access format. Database maintenance, quality control, and statistical analyses are outsourced to an external external CRO (contract research organization): currently ODDS, SL.

Ethics committee approval, auditing, and registration with the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality meet the requirements of the Spanish Data Protection Law 15/1999.

Statistical AnalysisVariables are presented as mean (standard deviation) and percentage. Results were classified by transplantation year, dividing the whole sample into six 5-year groups (although the most recent period, 2009-2012, only included 4 years). Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier test and were compared using the log rank test. Unless otherwise indicated, our analysis refers to the whole time series, including retransplantations and simultaneous transplantations. A P value of <.05 was considered significant.

RESULTSRecipient CharacteristicsIn 2012, the age of recipients was 52 (15) years and 82% were men; the most common baseline diagnoses were ischemic heart disease (30.9%) and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (24.8%). Recipient characteristics categorized in 4-year periods are shown in Table 3. Notably, in the most recent period, more than one-third of recipients were aged over 60 years and more than 25% were women. Similarly, we found an increase in risk conditions such as renal dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, infection in the 15 days prior to transplantation, and the need for mechanical ventilation prior to transplantation. The percentage of emergency transplantations has gradually increased to the current 36%. In contrast, retransplantation has remained stable at around 3%.

Recipient Characteristics in the Spanish Heart Transplantation Registry (1984-2012)

| 1984-1988 | 1989-1993 | 1994-1998 | 1999-2003 | 2004-2008 | 2009-2012 | P (tendency) | |

| Patients, no. | 207 | 1023 | 1517 | 1630 | 1385 | 999 | |

| Age, years | 41.5 (12.6) | 48.3 (13.3) | 50.9 (14.8) | 50.9 (14.4) | 50.1 (15.9) | 50.6 (16.8) | <.001 |

| <16 years, % | 4.3 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 7.0 | <.001 |

| >60 years, % | 2.4 | 15.2 | 29.4 | 27.9 | 29.1 | 34.2 | |

| Men, % | 85.0 | 85.9 | 80.9 | 81.2 | 77.8 | 74.8 | <.001 |

| BMI | 23.1 (3.6) | 24.7 (10.0) | 25.5 (21.7) | 25.8 (12.7) | 25.3 (7.2) | 25.1 (7.2) | .10 |

| Baseline etiology, % | <.001 | ||||||

| Dilated | 48.3 | 37.8 | 36.5 | 36.3 | 35.2 | 36.1 | |

| Ischemic | 32.9 | 41.5 | 44.5 | 42.8 | 35.5 | 36.2 | |

| Valvular | 9.2 | 10.7 | 8.5 | 6.7 | 8.2 | 6.5 | |

| Other | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 14.2 | 21.1 | 21.2 | |

| PVR, WU | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.2 (1.5) | .001 |

| Creatinine>2 mg/dl, % | — | 13.8 | 12.2 | 16.8 | 20.8 | 21.5 | <.001 |

| Bilirubin>2 mg/dl, % | 19.7 | 19.8 | 18.9 | 16.1 | 19.7 | 16.5 | .07 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, % | 8.3 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 15.3 | 16.3 | 17.4 | <.001 |

| Moderate-severe COPD, % | 6.0 | 10.0 | 12.3 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 7.9 | .01 |

| Previous infection, % | 2.5 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 13.4 | <.001 |

| Previous heart surgery, % | 21.8 | 26.0 | 28.5 | 24.6 | 27.4 | 28.9 | .06 |

| Heart retransplantation, % | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 2.0 | .12 |

| Pretransplantation mechanical ventilation, % | 4.4 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 15.8 | 15.9 | <.001 |

| Emergency transplantation, % | 9.5 | 19.8 | 24.1 | 23.1 | 30.5 | 36.4 | <.001 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistances.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean (standard deviation).

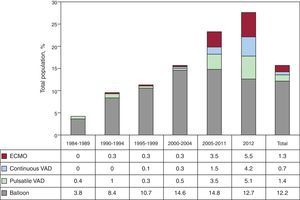

Since 2004, the use of mechanical circulatory support other than the traditional intra-aortic counterpulsation balloon has grown constantly. In 2012, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was used in 5.5% of procedures, continuous ventricular assist devices in 4.2%, and pulsatile devices in 5.1%. In the last year, the use of these devices (14.8%) surpassed that of the counterpulsation balloon as the only method of assistance (12.7%). The distribution of ventricular assist device procedures by periods is shown in Figure 2.

Donor Characteristics and Ischemia TimeIn 2012, the mean donor age was 39.7 (13.4) years (41.3% over 45 years); 71.0% were men. In 19.5% of procedures, donor weight exceeded recipient weight by 20%; the opposite occurred in 8.7%. In 19.5% of procedures, a male recipient received a graft from a female donor.

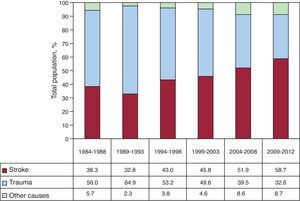

Donor characteristics are shown in Table 4; the causes of donor death are listed in Figure 3. In the periods described, the incidence of stroke as the main cause of death increased, as opposed to traumatic brain injury.

Donor Characteristics and Ischemia Time in the Spanish Heart Transplantation Registry (1984-2012)

| 1984-1988 | 1989-1993 | 1994-1998 | 1999-2003 | 2004-2008 | 2009-2012 | P (tendency) | |

| Patients, no. | 207 | 1023 | 1517 | 1630 | 1385 | 999 | |

| Age, years | 24.7 (8.1) | 26.9 (10.5) | 30.2 (12.3) | 32.5 (13.0) | 34.6 (13.8) | 38.7 (14.1) | <.001 |

| Age>45 years, % | 1.1 | 7.6 | 13.2 | 20.1 | 26.1 | 38.3 | <.001 |

| Men, % | 85.9 | 77.0 | 70.4 | 71.1 | 68.4 | 66.2 | <.001 |

| Female donor, male recipient, % | 11.7 | 18.8 | 22.3 | 19.7 | 20.6 | 20.1 | <.001 |

| Weight, kg | 67.7 (12.0) | 69.6 (13.6) | 68.4 (16.0) | 71.3 (15.7) | 72.3 (18.0) | 73.1 (18) | <.001 |

| Recipient/donor weight | 0.97 (0.19) | 0.98 (0.17) | 0.99 (0.22) | 0.98 (0.21) | 0.97 (0.21) | 0.94 (0.19) | .036 |

| Recipient/donor weight>1.20 | 10.5 | 11.1 | 16 | 12.3 | 12.2 | 6.6 | .02 |

| Recipient/donor weight<0.8 | 16.8 | 13.3 | 14 | 15.9 | 18.6 | 19.6 | .02 |

| Ischemia time, min | 132 (54) | 167 (61) | 182 (60) | 187 (63) | 202 (64) | 211 (62) | <.001 |

| <120min, % | 48.5 | 22.6 | 18.6 | 17.3 | 12.9 | 9.6 | <.001 |

| 120-180min, % | 30.5 | 37.4 | 29.6 | 27.1 | 24.1 | 19.7 | |

| 180-240min, % | 18.0 | 30.2 | 37.6 | 35.9 | 36.8 | 41.4 | |

| >240min, % | 3.0 | 9.8 | 14.2 | 19.7 | 26.2 | 29.2 |

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean (standard deviation).

Ischemia time gradually increased in the whole time series: in 2009-2012, ischemia time was nearly 1.30 h greater than in the initial period of 1984-1988. In the most recent period, ischemia time was >4 h in almost one-third of procedures (Table 4).

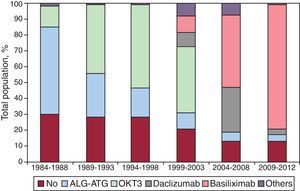

ImmunosuppressionIn 2012, 87.3% of recipients received some kind of induced immunosuppression treatment, usually basiliximab (85.2%). Figure 4 shows that induction gradually increased to its current almost widespread use. In the most recent period, more than 80% of patients received induction with interleukin-2 antagonists (basiliximab or daclizumab, mainly the former).

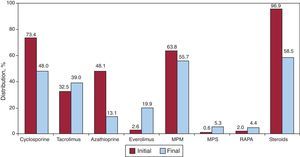

In 2012, initial immunosuppression was mainly with tacrolimus (75.9%) as a calcineurin inhibitor, mycophenolate mofetil (94.9%) as an antiproliferative agent, and steroids (96.4%). Figure 5 shows the drugs used in initial and end-of-follow-up immunosuppression for the whole time series. During the mean 6.7 years of follow-up, 58% of patients continued to receive corticoids. The use of tacrolimus has clearly tended to equal that of cyclosporine; azathioprine was barely used and, surprisingly, almost 1 of 4 patients was being treated with mTOR inhibitors (everolimus or sirolimus) at the last follow-up.

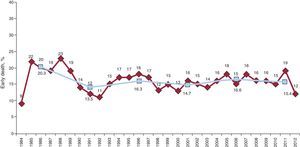

SurvivalFigure 6 shows the trend in surgical mortality (first 30 days post-surgery) by year and by 5-year periods. In 2012, mortality was 12%, slightly less than that of the historical cohort, which ranged, with slight variations, between 15% and 16%.

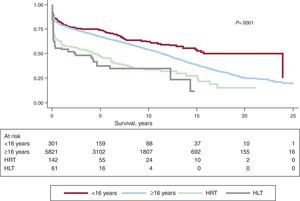

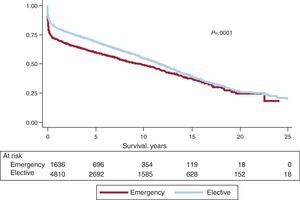

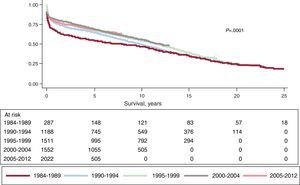

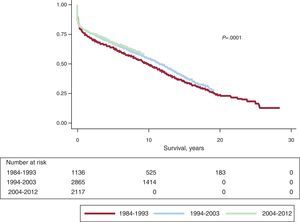

Actuarial survival in the whole time series at 1 month and at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years is shown in Figure 7. This represented approximately 2% to 3% mean annual mortality, with a median survival of 11.2 years. Differences by age and procedure type were significant. Survival was significantly worse in patients undergoing retransplantation and heart-lung transplantation vs first transplantation, both in adults and in recipients aged under 16 years old (Fig. 8). Similarly, significant differences appeared when emergency transplantations were compared with elective transplantations (Fig. 9) and according to the period when the procedure was performed (Fig. 10). Figure 10 shows that the results improved markedly after 1994, to the detriment of 1-year survival, which rose from 73% prior to this date, to 78% after 1994 (Fig. 11).

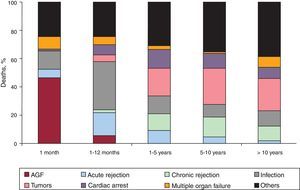

The causes of death changed according to the post-transplantation period under consideration (Fig. 12). In the first month post-transplantation, almost 50% of deaths were due to primary graft failure. After the first month and up to the end of the first year, acute rejection and, above all, infections were the main causes of death. After the first year, the main causes were tumors and different manifestations of graft vascular disease (chronic rejection, sudden death).

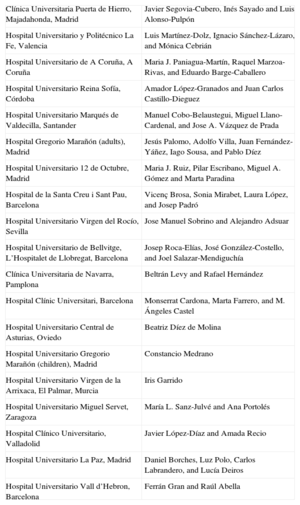

DISCUSSIONThe RETC is now nearly a quarter of century old and has undergone an increase in volume as a consequence of the greater number of transplantation centers, the accumulation of procedures performed and, especially, their complexity. The great strength of the RETC lies in successfully creating a registry of all heart transplantations performed in Spain since the first procedure in 1984 and in having adapted to changes in the procedure and in knowledge of transplantation over time. The continued efforts of all the Spanish programs have allowed the use of an online application to be implemented this year; this application enables RETC data to be updated in real time. This undoubtedly constitutes a very important means of improving the quality and productivity of the RETC. Sharing agreed, standardized, prospective data constitutes a research instrument and, above all, a clinical tool of immense value. This is particularly so in contexts such as heart transplantation in Spain, where implementation of the procedure is nationwide (18 centers currently have active programs) and, consequently, the volume per center is low. Obviously, only analysis of country-wide data can guarantee a minimum of consistency in the findings.

In 2012, 247 transplantations were performed—in line with figures for recent years. The falling number of transplantations since the peak reached in the late 1990s is common throughout Europe.24 The causes are probably multifactorial and complex. Without doubt, they include the scarcity of optimal donors—principally from traffic accidents—and the improved prognosis of the most frequent heart diseases; in the last decade, drug and instrumental treatments have been consolidated and delay the need for transplantation.

Analysis of time trends in the characteristics of transplantation may shed light on changes in clinical practice over time. Firstly, data show a gradual worsening in the clinical profile of recipients. The last 5 to 10 years have seen increases in the percentage of patients who are older, have worse renal function, more insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and are under mechanical ventilation. All these factors are known to affect short- and long-term prognosis.24 Similarly, the number of emergency procedures has increased, reaching nearly 40% in the last 4 years. We can only speculate about the causes of these trends. On the one hand, the increased experience of transplantation programs may have led to greater risk-taking with the inclusion of patients with a worse clinical profile. On the other hand, the tremendous advances in the medical and instrumental treatment of heart disease in the last 20 years have meant that patients receive prognoses similar to those for transplantation—until quite poor functional status has been reached25—which generally delays their inclusion on waiting lists and the performance of transplantation.

Similarly, criteria for donation have gradually been expanded. This can be seen in the significantly older mean age of donors and the percentage of older donors (>45 years) as well as in the increase in donors who have died from a stroke, frequently associated with a greater incidence of arteriosclerosis. This trend probably reflects the struggle of transplantation programs in the face of a growing scarcity of optimal donors.

The same tendency described for recipient and donor profiles is also evident in the surgical procedure, as the gradual lengthening of ischemia time seems to indicate. Remarkably, in the last 4 years, up to 29% of recipients had >4 h of ischemia time—which is considered the limit to ensure adequate graft viability. To date, we cannot put these delays down to the gradual worsening of logistic conditions affecting procedures—at least not in general. However, this worsening could be explained by an increasingly greater willingness to accept organs from geographically distant areas—especially for urgent transplantation—and by the effect of performing transplantations on patients with medium- and long-term circulatory assist devices, which occasionally lead to less predictable surgical procedures.

Nevertheless, the general results for mortality—following the first 10 years of activity (1984-1994), which could be classified as the founding years—have remained relatively stable and compare favorably with international registry data.24 Nonetheless, in general, surgical mortality has remained relatively high, making it a clear objective for improvement. We will have to see whether the coming years confirm a positive trend in this mortality, as data for 2012 appear to suggest.

The most remarkable innovation of the last 5 years is probably the increasing use of circulatory assist devices prior to transplantation since, in 2012, these have surpassed in percentage terms the use of the traditional intraaortic counterpulsation balloon. In Spain, these devices began to be deployed much later than elsewhere, very probably due to logistic reasons, mainly–but not always–due to economic limitations. It is still too early to determine the impact of these devices both on recruiting potential transplantation recipients and the status of recipients when they undergo the procedure and, therefore, their prognosis. Implementing these complex techniques involves a learning curve related, firstly, with an appropriate match between patient and technique, secondly, with managing these special clinical circumstances, and, thirdly, with establishing the ideal time to perform the transplantation following implementation. It is to be hoped that the individual effort and general shared knowledge derived from the transplantation centers through RETC support will lead to improved results in the coming years. Moreover, we predict that the greater use of circulatory support will lead to changes in selection criteria for emergency transplantation—an issue that is constantly changing and evolving and has significant repercussions on policy in assigning grafts.

We also detected time-scale changes in immunosuppression. Currently, induction is widely used, fundamentally with the administration of interleukin-2 inhibitors and, particularly, basiliximab. These potent inductors allow the introduction of calcineurin inhibitors to be delayed—an increasingly widespread practice in the context of peritransplantation kidney failure. In addition, their level of clinical tolerance is excellent, which contrasts with now obsolete drugs such as OKT3. Initial immunosuppression continues to be based on traditional triple therapy, although we have found a clear change in the selection of calcineurin inhibitors toward tacrolimus and in that of antiproliferative agent towards mycophenolate mofetil, to the detriment of cyclosporine and azathioprine, respectively. Furthermore, the use of m-TOR inhibitors (sirolimus and, above all, everolimus) has increased to reach the current total of 23% of patients, in the context of increasingly individualized immunosuppression therapy aimed at preserving renal function and preventing graft vascular disease and post-transplantation neoplasia.

CONCLUSIONSHeart transplantation is currently a well-established therapeutic treatment for selected patients with advanced-stage heart failure who are not candidates for other treatments. Although the clinical context in which this procedure is used has become ever more complex, the results remain within international parameters. However, potential improvements can be made in issues such as periprocedural mortality, the adequacy of immunosuppression, and long-term preventative care for major causes of mortality such as tumors, graft vascular disease, infections, and kidney failure. In the coming years, efforts must be maintained to effectively and efficiently introduce the pre- and postprocedural use of circulatory support devices into the standard management of patients suitable for heart transplantation.

FUNDINGThe RETC is partly funded by an unconditional grant from Novartis.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTF. González-Vílchez: remuneration for presentations: Astellas, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer. Expenses associated with travel, accommodation or attendance at scientific meetings: Roche, Astellas, Novartis.

We would like to thank ODDS, SL. for their help with the statistical analysis.

| Clínica Universitaria Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid | Javier Segovia-Cubero, Inés Sayado and Luis Alonso-Pulpón |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia | Luis Martínez-Dolz, Ignacio Sánchez-Lázaro, and Mónica Cebrián |

| Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña | Maria J. Paniagua-Martín, Raquel Marzoa-Rivas, and Eduardo Barge-Caballero |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Amador López-Granados and Juan Carlos Castillo-Dieguez |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander | Manuel Cobo-Belaustegui, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, and Jose A. Vázquez de Prada |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón (adults), Madrid | Jesús Palomo, Adolfo Villa, Juan Fernández-Yáñez, Iago Sousa, and Pablo Díez |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | Maria J. Ruiz, Pilar Escribano, Miguel A. Gómez and Marta Paradina |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Vicenç Brosa, Sonia Mirabet, Laura López, and Josep Padró |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | Jose Manuel Sobrino and Alejandro Adsuar |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | Josep Roca-Elías, José González-Costello, and Joel Salazar-Mendiguchía |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona | Beltrán Levy and Rafael Hernández |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | Monserrat Cardona, Marta Farrero, and M. Ángeles Castel |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo | Beatriz Díez de Molina |

| Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón (children), Madrid | Constancio Medrano |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | Iris Garrido |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | María L. Sanz-Julvé and Ana Portolés |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Javier López-Díaz and Amada Recio |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | Daniel Borches, Luz Polo, Carlos Labrandero, and Lucía Deiros |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Ferrán Gran and Raúl Abella |

Collaborators: Gregorio Rábago, Félix Pérez-Villa, José L. Lambert, Manuela Camino, Domingo Pascual, María T. Blasco, Luis de la Fuente, Luis García-Guereta, and Dimpna C. Albert.