This report describes the data reported to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry concerning the activity in cardiac pacing in 2017 in Spain.

MethodsThe analysis is based on the data obtained from the European Pacemaker Identification Card and the information reported by supplier companies related to global number of implanted pacemakers.

ResultsInformation was received from 106 hospitals, with a total of 12672 cards, representing the 32.1% of the total pacing activity. Conventional pacemaker and resynchronization pacemaker rate was 820 units/million and 26 units/million inhabitants respectively. A total of 333 leadless pacemakers were implanted. The mean age was 77.9 years, predominantly men (58.5%). Most electrodes were bipolar, with active fixation and only 20% had magnetic resonance protection. Atrioventricular block was the most common electrocardiographic disturb. Most patients received bicameral sequential pacing although single chamber VVIR pacing was used in up to 21.8% of patients. Patients older than 80 years benefited less from physiological pacing and resynchronization therapy.

ConclusionsTotal use of pacemaker generators remains stable with respect to 2016. Age is the main factor that influences pacing mode selection, which could be improved in around 22% of patients. Leadless pacing continues to rise.

Keywords

The national pacemaker data bank was created in 1990 to record cardiac pacing activity in Spain. The registry provides updated information on all aspects related to pacemaker implantation in order to take a census of patients with pacemakers and to statistically analyze various factors. The activity data of the previous year are published annually in Revista Española de Cardiología.1–16 The current report provides information on the pacemakers implanted in 2017, the profiles of the patients with such devices, and the trends and compares the results with those of neighboring countries

METHODSThis report was prepared by the Spanish Pacemaker Registry based on the information provided by the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card (EPPIC) submitted by the implantation centers. Because cards are not received for all implanted devices, the device suppliers also report the total numbers of generators implanted (pacemaker generators and high-energy [CRT-D] and low-energy [CRT-P] cardiac resynchronization therapy [CRT] devices), both in Spain as a whole and by autonomous community). This information is checked against that of Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Association)17 and the annual report published by the EHRA (European Heart Rhythm Association) on implantable electronic devices.18

The population data of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics on July 1, 2017 were used to calculate the rates per million population.19

This work includes cards corresponding to 12 672 procedures from 106 centers, with a total of 12 634 implanted generators (Table 1). According to the information provided by the industry, this number accounts for 32.1% of all devices in 2017, a figure similar to that of previous years.

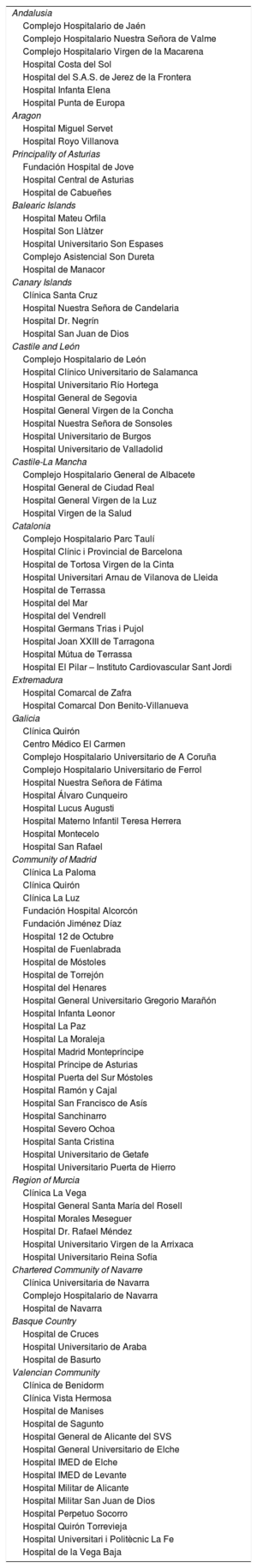

Public and Private Hospitals Submitting Data to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2017, Grouped by Autonomous Community

| Andalusia |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén |

| Complejo Hospitalario Nuestra Señora de Valme |

| Complejo Hospitalario Virgen de la Macarena |

| Hospital Costa del Sol |

| Hospital del S.A.S. de Jerez de la Frontera |

| Hospital Infanta Elena |

| Hospital Punta de Europa |

| Aragon |

| Hospital Miguel Servet |

| Hospital Royo Villanova |

| Principality of Asturias |

| Fundación Hospital de Jove |

| Hospital Central de Asturias |

| Hospital de Cabueñes |

| Balearic Islands |

| Hospital Mateu Orfila |

| Hospital Son Llàtzer |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases |

| Complejo Asistencial Son Dureta |

| Hospital de Manacor |

| Canary Islands |

| Clínica Santa Cruz |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora de Candelaria |

| Hospital Dr. Negrín |

| Hospital San Juan de Dios |

| Castile and León |

| Complejo Hospitalario de León |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca |

| Hospital Universitario Río Hortega |

| Hospital General de Segovia |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Concha |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos |

| Hospital Universitario de Valladolid |

| Castile-La Mancha |

| Complejo Hospitalario General de Albacete |

| Hospital General de Ciudad Real |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz |

| Hospital Virgen de la Salud |

| Catalonia |

| Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí |

| Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona |

| Hospital de Tortosa Virgen de la Cinta |

| Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida |

| Hospital de Terrassa |

| Hospital del Mar |

| Hospital del Vendrell |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol |

| Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona |

| Hospital Mútua de Terrassa |

| Hospital El Pilar – Instituto Cardiovascular Sant Jordi |

| Extremadura |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra |

| Hospital Comarcal Don Benito-Villanueva |

| Galicia |

| Clínica Quirón |

| Centro Médico El Carmen |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora de Fátima |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro |

| Hospital Lucus Augusti |

| Hospital Materno Infantil Teresa Herrera |

| Hospital Montecelo |

| Hospital San Rafael |

| Community of Madrid |

| Clínica La Paloma |

| Clínica Quirón |

| Clínica La Luz |

| Fundación Hospital Alcorcón |

| Fundación Jiménez Díaz |

| Hospital 12 de Octubre |

| Hospital de Fuenlabrada |

| Hospital de Móstoles |

| Hospital de Torrejón |

| Hospital del Henares |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón |

| Hospital Infanta Leonor |

| Hospital La Paz |

| Hospital La Moraleja |

| Hospital Madrid Montepríncipe |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias |

| Hospital Puerta del Sur Móstoles |

| Hospital Ramón y Cajal |

| Hospital San Francisco de Asís |

| Hospital Sanchinarro |

| Hospital Severo Ochoa |

| Hospital Santa Cristina |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro |

| Region of Murcia |

| Clínica La Vega |

| Hospital General Santa María del Rosell |

| Hospital Morales Meseguer |

| Hospital Dr. Rafael Méndez |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía |

| Chartered Community of Navarre |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra |

| Hospital de Navarra |

| Basque Country |

| Hospital de Cruces |

| Hospital Universitario de Araba |

| Hospital de Basurto |

| Valencian Community |

| Clínica de Benidorm |

| Clínica Vista Hermosa |

| Hospital de Manises |

| Hospital de Sagunto |

| Hospital General de Alicante del SVS |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche |

| Hospital IMED de Elche |

| Hospital IMED de Levante |

| Hospital Militar de Alicante |

| Hospital Militar San Juan de Dios |

| Hospital Perpetuo Socorro |

| Hospital Quirón Torrevieja |

| Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe |

| Hospital de la Vega Baja |

In 2017, the autonomous community of Cantabria did not submit European Pacemaker Patient Identification Cards to the registry.

Even considering the sample analyzed as representative of the national total, an important consideration is that less than 100% of the cards were returned and that, in a not insignificant number of cases, the cards were incompletely completed. The percentage of missing data varied widely: 0.2% for lead position, 16.2% for age, 18.9% for reason for generator explantation, 23.1% for lead polarity, 27.1% for sex, 27.6% for type of lead fixation, 41.4% for electrocardiogram results, 49.3% for preimplantation symptoms, 60.9% for etiology, and 89.7% for reason for lead explantation. The percentages reported in this article were calculated based on the data available for each parameter.

Numbers of Pacemaker Generators ImplantedAccording to the data provided by the companies, 38 190 conventional pacemaker generators and 1214 CRT-P generators were implanted in Spain in 2017 (total, 39 404 cardiac pacing devices). According to Eucomed, 39 177 devices were implanted.17

According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, the total Spanish population as of July 1, 2017, was 46 549 045 (0.2% more than the previous year), with 22 838 035 males and 23 711 009 females.

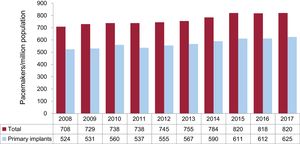

Considering these data, the implantation rate of conventional pacemakers during 2017 was 820/million population according to Spanish Pacemaker Registry data and 816/million population according to Eucomed (Figure 1).

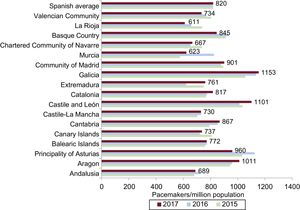

Regarding autonomous communities, Galicia, Castile and León, and Aragon were at the head of the list with more than 1000 units/million population, followed by the Principality of Asturias and Cantabria, with 960 and 867 units/million population, respectively. The Region of Murcia and La Rioja were the communities with the lowest implantation rates, with less than 650 units/million population (Figure 2).

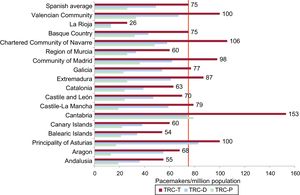

Cardiac Resynchronization DevicesAccording to Spanish Pacemaker Registry data, 3506 CRT-T units were implanted in Spain in 2017 (2292 CRT-Ds and 1214 CRT-Ps), giving a rate of 75 units/million population. The CRT-P device rate was 26/million population according to the data available in the Spanish Pacemaker Registry. These figures are the same as those provided by Eucomed.

Cantabria was the community with the most CRT-T implants (153 units/million population), followed by the Chartered Community of Navarre, Principality of Asturias, and Valencian Community (around 100 units/million population). La Rioja had the lowest implantation rate, with 26 units/million population, a figure somewhat lower than the implantation rate of the previous year. For CRT-P devices, Cantabria and the Chartered Community of Navarre continue to lead the list with 79 and 48 units/million population, respectively. Extremadura experienced a 48% decrease in the CRT-P rate vs 2016, with 28 units/million population (Figure 3).

Age and Sex of the PopulationPacemaker use continues to be higher in men than in women (58.5% vs 41.5%), both in primary implants (58.9% vs 41.1%) and in replacements (57.1% vs 42.9%).

The average age of patients with a pacemaker remains high: 77.9 years, somewhat higher in women than in men (78.9 years vs 77.1 years) and for replacements than primary implants (79.7 vs 77.5 years). The highest percentage of implants was in the age range 80 to 89 years (44.3%), followed by 70 to 79 (29.0%), 60 to 69 (11.4%), and 90 to 99 (9.2%). The percentage was significantly lower in patients younger than 60 years (5.9%) and in those older than 99 years (0.2%).

Symptoms and EtiologyThe predominant reason for pacemaker implantation was syncope (40.1%), followed by dizziness (24.9%), bradycardia (11.8%), heart failure (14.6%) and, less frequently, prophylactic reasons (4%), tachycardia (1.2%), and other atypical symptoms, such as chest pain (0.9%), brain dysfunction (0.5%), aborted sudden cardiac death (0.4%), and unspecified causes (1.6%).

As in previous years, unknown etiology or conduction system fibrosis was the most frequent cause of the conduction disorder (84.9% of cases); the other causes occurred at low percentages: iatrogenic due to surgical complication, ablation, or medication (4.7%), ischemic heart disease (2.6%), postinfarction (0.5%), valvular heart disease (2.1%), cardiomyopathies (2.0%), congenital heart disease (0.6%), carotid sinus syndrome (0.4%), vasovagal syncope (0.2%), heart transplant (0.2%), and, with less than 0.1%, myocarditis and endocarditis. Unspecified causes accounted for 1.7%.

Preimplantation ElectrocardiogramThe most common preimplantation abnormality is still atrioventricular block (AVB) (58.3%), mainly third-degree AVB (38.7%), followed by second-degree AVB (13.9%), first-degree AVB (1.45%), and atrial fibrillation (AF)/atrial flutter with complete heart block (4.2%). Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) was the second most common abnormality, with 32.6% of cases, particularly, slow AF (14.2%), bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (7.2%), sinus bradycardia (4.9%), and, less frequently, sinoatrial block/arrest (2.7%) and chronotropic incompetence (0.1%). Unspecified SSS corresponded to 3.5%. Bundle branch block or intraventricular conduction disorder (IVCD) occurred in 5.6% of cases. Atrial tachycardia motivated 0.3% of implantations and ventricular tachycardia, 0.1%. Sinus rhythm with or without electrophysiological abnormalities corresponded to 2.9% and an unspecified rhythm to 0.2% (Figure 4).

Regarding the differences by sex, AVB (except blocked AF) was more common in men (54.9% vs 52.9%), whereas SSS (excluding slow AF) was more frequent in women (23.4% vs 15.7%). Slow or blocked AF constituted 18.9% of the indications for men and 16.3% of those for women. Bundle branch block was more common in men (7.1% vs 3.8%).

Implantations and Generator and Lead ReplacementsOf generators implanted, 76.2% were primary implants, 22.4% were generator replacements, 1.1% were generator and lead replacements, and 0.3% were lead replacements alone.

The total number of generator explantations increased to 2997, mainly due to battery depletion (89.6%) and, less frequently, elective replacement (2.4%), erosion/infection (1.8%), premature depletion due to elevated thresholds or programmed high-output energy (1.8%), advisories (0.9%), hemodynamic optimization due to pacemaker syndrome (0.9%), and other rare causes (<1% of explants).

The total number of lead explantations was 175, mainly due to infection or ulceration (55.8%), and, less frequently, dislodgment (5.5%), undersensing (5.5%), advisories (5.5%), insulation failure (5.5%), elective explantation (5.5%), and unspecified causes (16.7%).

Lead CharacteristicsAbout 99.9% of the leads were bipolar: 100% of those of the atrium, 99.9% of those of the right ventricle (RV), and most of those implanted in the tributary vein of the coronary sinus (93.6%).

The use of active fixation leads (88%) continues to predominate in all age groups, in both the atrium (88.9%) and the RV (87.5%).

In total, 19.4% of the leads were magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compatible, with similar numbers for the atrium (20.4%) and the ventricle (19.1%) and for patients older and younger than 80 years of age (16% and 17.4%, respectively).

Leadless PacemakersIn 2017, 333 units of the leadless pacemaker Micra (Medtronic) were implanted, 67% more than in 2016.16 Leadless pacemakers have been implanted in 12 autonomous communities. The 3 with the most implantations (Catalonia, 78; Galicia, 70; the Valencian Community, 45) accounted for 58% of the total activity. Leadless pacing represented 2.2% of all VVI/R devices implanted in 2017.

Pacing in Pediatric PatientsA total of 43 pacemaker generators were implanted in patients ≤ 14 years (0.1%), most (77%) during the first year of life.

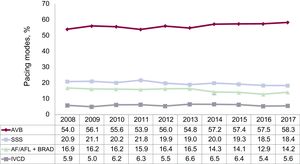

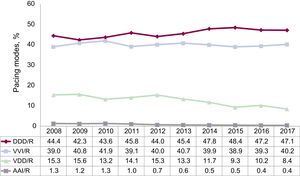

Pacing ModesSingle-chamber pacing accounted for 40.6% of the total. This percentage includes single-chamber atrial pacing (AAI/R), which represented 0.4%, continuing its downward trend (Figure 5). The number of primary implants in the AAI/R mode continues to decrease (0.2%), as does the number of generator replacements (–0.7% of the total). Single-chamber ventricular pacing (VVI/R) continues its upward trend with 40.2%, mainly due to a slight increase in primary implants (40.9%) because the number of generator replacements (38.1%) fell slightly vs 2016.16 Taking into account the electrocardiographic diagnosis prior to implantation, with only 18.4% of implantations in patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia, an estimated 21.8% of patients receiving single-chamber ventricular pacing could have received a pacemaker capable of maintaining atrioventricular (AV) synchrony. The various factors affecting the final decision on pacing mode are analyzed in the following section.

One- or 2-lead dual-chamber sequential pacing constituted 55.5% of the generators implanted in 2017.14–16 The use of single-lead sequential pacing (VDD/R) has decreased from the previous year and represented 8.4% (Figure 5), mainly due to a lower number of primary implants (6.2%) because the number of replacements has increased vs 2016 (15.6%). Two-lead dual-chamber pacing (DDD/R) continues to be the most used mode, stable at around 47.1% of all generators implanted, 49.1% of primary implants and 40.5% of replacements. The use of biosensors was practically standard practice in DDD/R devices (98.7%).

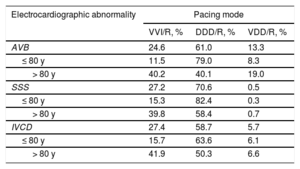

Pacing Mode SelectionAtrioventricular BlockTo assess the degree of adequacy of the most recommended pacing modes,20 our analysis was limited to patients in sinus rhythm and excluded patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia with AVB, EPPIC code C8; factors possibly influencing pacing mode selection were analyzed, such as degree of block and patient age and sex.

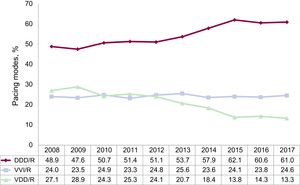

Atrial synchronous pacing (DDD/R and VDD/R modes) predominated (74.3%) and use of the DDD/R mode (61.0%) has remained stable, whereas there was a slight decrease in the VDD/R mode (13.3%) and a slight increase in the VVI/R mode (24.6%) (Figure 6).

Age continues to determine the pacing mode chosen. In patients younger than 80 years, pacing maintaining AV synchrony had a clear majority (87.3%), and the DDD/R mode increased vs the previous year due to decreased use of the VDD/R mode (8.3%). In contrast, in patients older than 80 years, AV synchrony maintenance was much less frequent (59.1%), with greater use of the VDD/R mode (19%) to the detriment of DDD/R (40.1%) (Table 2). Single-chamber ventricular pacing increased vs the previous year (Table 2).

Distribution of Pacing Modes by Electrocardiographic Abnormality and Age Group in 2017

| Electrocardiographic abnormality | Pacing mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VVI/R, % | DDD/R, % | VDD/R, % | |

| AVB | 24.6 | 61.0 | 13.3 |

| ≤ 80 y | 11.5 | 79.0 | 8.3 |

| > 80 y | 40.2 | 40.1 | 19.0 |

| SSS | 27.2 | 70.6 | 0.5 |

| ≤ 80 y | 15.3 | 82.4 | 0.3 |

| > 80 y | 39.8 | 58.4 | 0.7 |

| IVCD | 27.4 | 58.7 | 5.7 |

| ≤ 80 y | 15.7 | 63.6 | 6.1 |

| > 80 y | 41.9 | 50.3 | 6.6 |

AVB, atrioventricular block; DDD/R, sequential pacing with 2 leads; IVCD, intraventricular conduction defect; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VDD/R, single-lead sequential pacing; VVI/R, single-chamber ventricular pacing.

As was the case in previous years, when atrial-based pacing was analyzed according to the degree of AVB, a trend toward its greater use was observed in patients with first- or second-degree AVB (77.9%) vs patients with third-degree AVB (72.9%). However, these differences were minimal in the case of patients younger than 80 years of age (89.3% and 86.4%, respectively), whereas they were somewhat more pronounced in the population older than 80 years of age (65.5% and 56.6%).

The differences according to sex in the choice of pacing mode persist. DDD/R pacing was more frequently used in men (65.5% vs 54.5%), whereas VDD/R pacing was slightly more common in women (18.7% vs 12.4%). These differences were still observed according to age range. In women younger than 80 years, the percentage use of the DDD/R mode continues to be lower than in men, as was the case in previous years (75.2% vs 80.8%), due to greater use of both the VDD/R (11.9% vs 7.4%) and VVI/R (11.9% vs 10.2%) modes. Accordingly, sequential pacing in women younger than 80 years of age was very similar in the 2 sexes (88.2% in men and 87.1% in women). Notably, in women older than 80 years, the use of the VVI/R mode exceeded that of the DDD/R (37.9% vs 37.3%).

Finally, 24.6% of patients with an electrocardiographic diagnosis of AVB while maintaining sinus rhythm continue to receive VVI/R pacing. This figure was even higher in older patients (40.2% in those older than 80 years old) and higher for third-degree AVB and in women of both age bands.

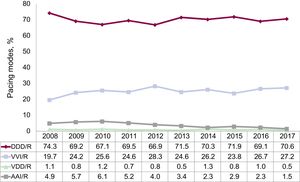

Intraventricular Conduction DefectsThe DDD/R pacing mode continues to predominate in this group (58.7% of implantations), with a significant increase vs 2016.16 Accordingly, there was decreased use of the VVI/R (27.4%) and VDD/R (5.7%) modes. The use of CRT-P devices in patients in sinus rhythm with an IVCD (7.2%) continues to decrease, whereas biventricular pacing in patients with permanent AF increased slightly vs 2016 (1.0%). Pacing types that maintain AV synchrony remain predominant (64.4% of implantations) (Figure 7). In general, the pacing mode in this subgroup of patients also depended on age, as was the case with AVB (Table 2).

The use of CRT-P devices to treat ventricular dysfunction experienced a slight decrease (–8.1%). This fall is due to lower use of these devices in older patients (1.2%) because it has increased in those younger than 80 years (14.7%).

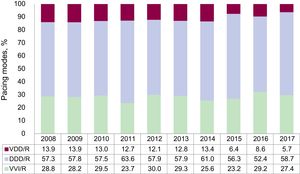

Sick Sinus SyndromeThe adequacy of the pacing modes to the recommendations of the current clinical practice guidelines20 was assessed by dividing the patients into 2 large groups: in the first group, patients who theoretically are in permanent AF or atrial flutter and have bradycardia (EPPIC code E6); in the other group, those who are theoretically in sinus rhythm.

A. Sick sinus syndrome in permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia. The vast majority of the generators implanted were VVI/R devices (91.6%) but, strikingly, the use of the DDD/R generator has increased to 6.4% and 0.4% of units continue to be VDD/R devices, the latter being hardly justifiable for SSS. The use of the DDD/R mode can be justified when sinus rhythm restoration is expected. Similar to 2016, 1.5% of patients received a CRT-P device.

B. Sick sinus syndrome in sinus rhythm. As recommended by the current clinical practice guidelines,20 the most widely used pacing mode continued to be DDD/R (Figure 8). Both pacing in AAI/R mode and in VDD decreased vs 2016 and remained at very low levels, probably due to adherence to the latest recommendations.20 Importantly, the use of the VDD/R mode in SSS is not appropriate unless there are other factors involved, such as a technically challenging atrial lead implantation.

Trends in pacing modes in sick sinus syndrome, 2008 to 2017 (excluding EPPIC code E6: chronic atrial fibrillation and bradycardia). AAI/R, single-chamber atrial pacing; DDD/R, sequential pacing with 2 leads; VDD/R, single-lead sequential pacing; VVI/R, single-chamber ventricular pacing.

By separately analyzing the different electrocardiographic manifestations of SSS, excluding EPPIC subgroups E7 and E8 (interatrial block and chronotropic incompetence) due to their minimal representation over the years, the VVI/R pacing mode percentage can be seen to vary between 19.4% and 35.3% and, once again, the highest percentage corresponded to bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (EPPIC subgroup E5). Nonetheless, these numbers may be increased by the erroneous inclusion of patients with slow-fast permanent AF episodes in this group and not in the already discussed E6 group.

Regarding the influence of age, pacing modes allowing atrial detection and pacing were used more frequently in patients up to 80 years of age (Table 2). Regarding the influence of sex, in the older population group (>80 years), the VVI/R mode was used in 39.4% of women and in 32.9% of men. In patients up to 80 years, the VVI/R mode was used much less commonly and was more frequent in women (17.0% vs 12.8%).

Remote MonitoringIn 2017, 4748 conventional pacemakers (12.4% of implanted pacemakers) and 291 CRT-P devices (24% of implanted CRT-Ps) were included in a remote monitoring program. As for CRT-D, 1546 devices were included, representing 67.6% of the total.

DISCUSSIONAs in previous years, the quality of the sample continues to show room for improvement, given that only 106 centers provided EPPIC data (fewer than in previous years) and that a considerable percentage of data is lost or missing from the cards. For this reason, implementation of the smartphone application designed in conjunction with the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices is important, as well as its extensive use in implantation centers, which would increase the size of the sample, as well as its reliability and representativeness.

During 2017, the use of pacemaker generators was practically unchanged vs 201616 (–0.3% according to Eucomed and+0.4% according to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry), which breaks with the upward trend of previous years. However, the increase in the number of implanted devices had already slowed down in 2016, after a 5% increase in generator implantation in 2015. This lack of growth affected both conventional pacemakers and CRT-P devices. The implantation rate recorded by the Spanish Pacemaker Registry was 820 units/million population, lower than the European average (949 units/million population). Nonetheless, this European average is affected by the high rate of implantations in countries such as Germany, Belgium, Italy, and Finland, which exceed 1000 units/million population. The economic factor cannot be considered the sole determinant of this difference because some countries with lower implantation rates have higher per capita income and higher spending on health, such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Norway, and Switzerland, whereas countries such as Greece and Portugal, with lower per capita income, have rates close to 900 and 1000 implantations/million population.17 The differences among countries may be influenced by differences in health management, availability of human resources, training programs, and even the type of funding, considering the copayment system found in some countries. It should also be noted that, after several years of progressive growth, the European average has experienced a fall vs 2016 (965 implantations/million population).

The number of CRT-T devices decreased by 4.7% vs 2016, and the rate also fell from 79 units/million population to 75. This decrease affected both CRT-P and CRT-D devices, particularly the latter (–1.1% and –6.5% in the number of devices, respectively), giving a CRT-D/CRT-P ratio of 1.9/1. CRT-P devices constituted 34.6% of cardiac resynchronization activity in Spain in 2017, and the rate has practically remained constant vs the previous year (26 units/million population). This figure is still clearly lower than the European average (53 units/million population) and is one of the lowest of the countries reporting their data to Eucomed, only exceeding Greece and Poland with 9 and 20 units/million population, respectively. Denmark, Sweden, France, and Switzerland are the countries with the highest implantation rates.17 Again, the economic factor is not the only reason for the low implantation rate in Spain because countries such as Portugal, with a lower gross domestic product and health expenditure than Spain, have a higher implantation rate (36 units/million population). Nor can the number of CRT implantation centers explain the low rate, given that Spain had an average of 2.7 centers/million population in 2016, similar to that of neighboring countries such as France, Sweden, and Portugal.18 One possible cause is an indication defect due to a lack of arrhythmia/heart failure units that act as referral centers. The SEC-Excellence project of the Spanish Society of Cardiology includes a heart failure process whose objective is to define standards for both the clinical management of patients with heart failure and the heart failure units managed by cardiology services.21 The lack of adherence to clinical guidelines may also have influenced the low rate of CRT-P device implantations.22 Age continues to be an important factor at the time of CRT-P device implantation in patients with IVCD. Although the elderly population was poorly represented in the large clinical trials that evaluated the benefit of CRT, more and more studies report a clinical benefit and improved echocardiographic parameters in octogenarian patients, with survival rates similar to or only slightly lower than the same-aged population not receiving this therapy.23

For distribution by autonomous community, those with the highest pacemaker implantation rates were Galicia, Castile and León, and Aragon (>1000 units/million population), probably because they have an older population. La Rioja is still the community with the lowest number of implantations and the Region of Murcia returns to figures before 2016 (around 600 units/million population) after a rebound last year. For CRT-P devices, as in 2016, Cantabria and the Chartered Community of Navarre stand out, with more than 50 units/million population. The differences in resynchronization rates are probably influenced by factors such as the economic climate, population age, and health system structure and organization.

Men predominate in the use of devices (58.5%), both in primary implants and in replacements, and pacemaker use continue to be a condition and a therapy characteristic of advanced age, with more than 50% of the implantations performed in elderly patients older than 80 years.

The most common electrocardiographic abnormality prior to implantation remains AVB (54.1%), particularly third-degree AVB, at 38.7%. SSS was the second most common indication, at 18.4% of all indications. Slow or blocked AF also represented a significant percentage of implantations (18.4%). Bundle branch block remains the least frequent abnormality (5.6%).

Regarding the leads implanted, practically all were bipolar, both in the atrium and in the ventricle, and also in the coronary sinus, where monopolar leads predominated until 2 years ago. The use of tetrapolar leads, already common in clinical practice because of their advantages in terms of the various electronic configurations offered, is not considered in the cards because it is possible to choose the configuration with the best electrical behavior and without phrenic stimulation. Neither is there information on multipoint pacing. Studies published in recent years have revealed the acute hemodynamic benefits of this therapy, as well as the mid- to long-term improvement in the echocardiographic parameters of asynchrony.24 Regarding the type of fixation, most implantations involved active fixation leads, both in the atrium and in the ventricle, and in all age groups. Their advantages in terms of the possibility of implantation in alternative sites, both in the atrium and in the ventricle, and their optimal electrical behavior have probably contributed to their widespread use. The use of MRI-compatible leads25 is still suboptimal, although a slight increase was observed vs 2016 (19.4% vs 16.1%). We do not know the percentage of MRI-compatible generators, but their higher cost may have resulted in low implementation.

Leadless pacing continued to grow, with 333 units in 2017, representing a 67% increase vs 2016. However, in 5 autonomous communities, this type of device is not implanted and most are implanted in just 3 (58% in Catalonia, Galicia, and the Valencian Community). Although these pacemakers are still more expensive than conventional VVI/R pacemakers, the progressive increase in the number of such implantations is due to the long-term advantages of the absence of leads in the vascular space, the greater availability of this technology, and the scientific evidence corroborating their effectiveness and mid-term safety.26

For the first time in the registry, information on pacing in the pediatric population has been provided. A total of 43 implantations were recorded in patients younger than 14 years. More than three-quarters were performed during the first year of life.

Atrial synchronous pacing continues to be the most used approach in patients with AVB, but age still determines the pacing mode in this setting.

The DDD/R mode continues to predominate in SSS, although the VVI/R mode is still used in 27.2% of cases, slightly more than in the previous year, and age is still a fundamental factor when the pacing mode is being chosen for these patients. Thus, single-chamber VVI/R pacing is more frequent in patients older than 80 years and with bradycardia-tachycardia-like SSS, possibly due to the risk of a near-future fall in those with permanent AF or because patients with slow-fast permanent AF have been mistakenly included in this group. In any case, as recommended by the current guidelines, the DDD/R mode is the most suitable for SSS, mainly due to its ability to reduce the incidence of AF and stroke and the risk of pacemaker syndrome that can impair patients’ quality of life. AAI/R pacing mode has declined again, in accordance with the current clinical practice guidelines, based on the results of the DANPACE trial27 and the drawbacks of this pacing mode, given that 0.6% to 1.9% of patients with SSS develop AVB each year. In atrial tachyarrhythmia with a slow ventricular response, the predominant mode is still VVI/R.

During 2017, 12.4% of conventional pacemakers and 24% of CRT-P pacemakers were included in a remote monitoring program. These percentages are similar to those reported the previous year but lower than those of the last EHRA report on the implementation and financing of remote monitoring in Europe (22% of conventional pacemakers and 69% of CRT-Ts).28 Funding is the main limitation perceived by implantation centers surveyed on the implementation of remote monitoring. Taking into account the demonstrated benefit of remote monitoring in terms of the detection and early treatment of clinical and technical events in patients with devices, the application of this technological advance in Spain should be considered insufficient.

CONCLUSIONSDuring 2017, the number of implanted pacemakers remained stable, with a slight decrease in the total number of CRT-P devices. More than 50% of implantations performed in patients older than 80 years, precisely those patients who receive a less physiological mode of pacing and with a lower rate of CRT-Ps. The use of leadless pacemakers continues to rise and these devices are consolidated as an effective and safe technique in the medium term, and the application of remote monitoring for device follow-up remains constant, despite the proven advantages. The quality of the sample needs to be improved to enable a more reliable interpretation of Spanish Pacemaker Registry data.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.