Keywords

INTRODUCTION

This article is the annual update analysis of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Sociedad Española de Cardiología) Working Group on Heart Transplantation. We present the results of heart transplants performed in Spain between May 1984, when the first such operation was performed, and December 31, 2003, when the current data set was closed.1-14

This comprehensive Registry report includes data on all heart transplants performed by teams at all centers in Spain. Therefore, it is an accurate account of the status of heart transplantation in the country. The reliability of the report is founded on the use by all of the teams of a similar database constructed on mutually agreed principles, which unifies possible responses and standardizes variables.

HEART TRANSPLANTS PERFORMED

The Registry currently includes 18 heart transplantation centers (Table 1), although only 17 of them performed transplants in 2003. In contrast to previous years, 2003 saw a stabilizing of the number of active centers. Most transplantation centers believe it unwise to increase the number of centers as the benefit gained from shorter travel distances for patients is offset by the fact that new centers are considerably slow in gaining the necessary experience to ensure good results.

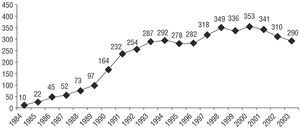

In the 19 years that heart transplantation procedures have been performed in Spain, the total number of operations has reached 4386. Figure 1 presents the distribution of heart transplants by year, 96% of which were isolated orthotopic transplants. Table 2 shows the distribution of transplants by procedure type.

Figure 1. Number of heart transplants by year.

HEART TRANSPLANT RECIPIENT PROFILE AND UNDERLYING HEART DISEASE

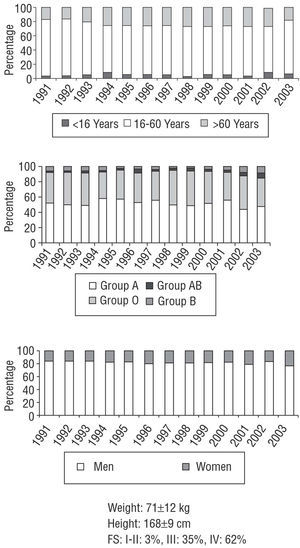

In Spain, the profile of the average heart transplant recipient is that of a man of approximately 50 years of age, belonging to blood group A. Percentages of children, older adults, or women are comparatively low. Figure 2 presents the general characteristics of transplant recipients.

Figure 2. Annual distribution by age, blood group, and gender. Weight, height, and recipient functional status. FS indicates functional status.

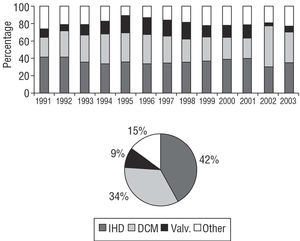

Heart transplantation is most frequently indicated for ischemic heart disease, followed by idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Together, these 2 diagnoses account for 76% of all causes. Other specific causes are relatively infrequent, except for valvular heart disease (9%). Figures 3 and 4 show the distribution of pathologic processes that are indications for heart transplantation.

Figure 3. Underlying diseases indicating transplantation and their annual distribution. IHD indicates ischemic heart disease; DCM, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy; Valv., valvular heart disease.

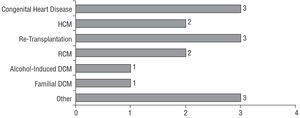

Figure 4. Less frequent diseases indicating transplantation. The number at the end of each column represents the corresponding percentage of the total. DCM indicates dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy.

WAITING LIST MORTALITY AND URGENT TRANSPLANTATION

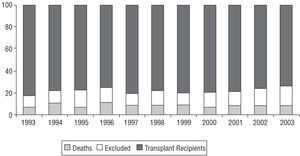

In 2003, waiting list mortality was 9%. The percentage of patients excluded from transplant after placement on the waiting list was 22%. Figure 5 shows the annual percentages of waiting list patients who received a transplant, patients removed from the list without receiving a transplant, and patients who died before receiving a transplant.

Figure 5. Percentage annual distribution of patients who died, patients removed from waiting lists and transplant recipients.

The percentage of indications for urgent transplantation has varied, sometimes substantially, over the years. Often, there has been no obvious explanation for this. Last year, urgent transplants accounted for 29% of procedures. This is a clear increase over 2002 (26%) and is above the average for the last 5 years (21%). Figure 6 shows the evolution of indications for urgent transplantation over the years.

Figure 6. Annual changes (percentage) in indications for emergency transplantation.

RESULTS

Survival

Early mortality (death within 30 days of transplant) in 2003 was 13%. Figure 7 shows the evolution of early mortality over the years.

Figure 7. Evolution of percentage early mortality rate by years.

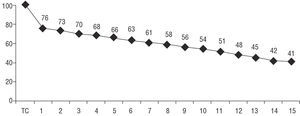

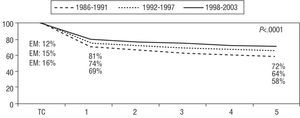

When survival rate data for 2003 were added to those of previous years, we obtained 1-, 5-, and 10-year actuarial survival rates of 76%, 66%, and 54%, respectively, with an average recipient survival of 11.4 years. Figure 8 shows the actuarial survival curve, with an initially sharp decrease over the first year (essentially due to deaths within the first month) followed by a less marked decline of approximately 2.2% per year. Figure 9 shows that substantial differences exist when the overall survival curve is analyzed by periods.

Figure 8. Actuarial survival curve (Kaplan-Meier). Horizontal axis shows years post-transplantation.

Figure 9. Survival curve by periods. Horizontal axis shows years. EM indicates early mortality.

Causes of Death

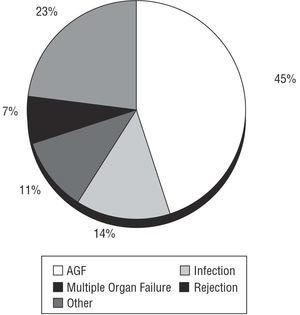

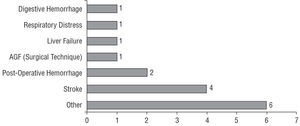

The most frequent cause of death during the early period was acute graft failure (45%). Figure 10 shows the distribution of causes of death during the first month.

Figure 10. Causes of early mortality. AGF indicates acute graft failure.

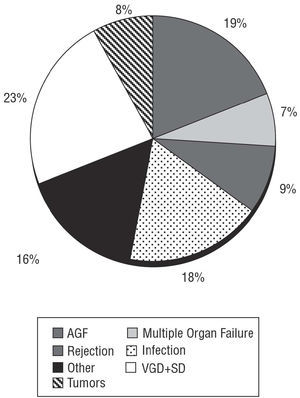

The most common causes of overall mortality 30 days after transplantation were the combination of vascular graft disease and sudden death, acute graft failure and infection. Figures 11 and 12 show incidence of causes of overall mortality.

Figure 11. Causes of overall mortality. AGF indicates acute graft failure; VGD+SD, vascular graft disease and sudden death.

Figure 12. Less frequent causes of overall mortality. The number to the end of each of the columns represents percentage with respect to the total. AGF indicates acute graft failure.

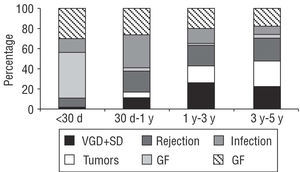

When causes of mortality are analyzed by periods, differences can be seen in the first month (acute graft failure), between the first month and the first year (infection), and after the first year (tumors and the combination of vascular graft disease and sudden death). Figure 13 shows how the distribution of causes of mortality varies by periods.

Figure 13. Causes of mortality by periods. Y indicates year(s); d, day(s); VGD+SD, vascular graft disease and sudden death; GF, graft failure.

DISCUSSION

In Spain, the early days of heart transplantation are long gone and today we can call on a wealth of experience with this procedure. Our results are on a par with those achieved in other countries in both Europe and North America, as any analysis of the annual report of the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation reveals.15-17 The fact that our Registry comprises information provided by all transplant teams in the country and that it is founded on an agreed, standardized database reinforces the validity of these results. All teams update their results annually and submit their figures to the Registry coordinator who, with the help of custom-built software, introduces the data into a common database to facilitate analysis of the variables. We believe this method greatly enhances the reliability of our results and avoids errors of the kind so often found in non-standardized databases.

Last year, the number of active transplantation centers in Spain remained stable. This is an encouraging sign, as the number of operating centers is a source of concern. The number of optimal donors has remained constant whereas the number of transplants per center has decreased. The fact that fewer transplant procedures are being performed leads to under use of resources in those hospitals prepared to undertake a large number of transplants, and to an increase in the time needed to learn skills and achieve suitable results. The only tangible benefit for the patient is the convenience of not having to travel to a different part of the country in order to receive a transplant.

Since heart transplantation was first performed in Spain, there has been an almost constant increase in the number of procedures. However, the rate of increase was greatest between 1989 and 1993, when it grew from 97 to 287 transplants. Since 1993, the annual rate of increase has been slower. Only once, in 2000, has the volume of transplants slightly exceeded 350. This is considered the volume-per-year plateau, given our expectations for the number of donors per year and current criteria for accepting donor hearts. Nevertheless, in 2003 there was a general decrease in the number of transplants, with longer waiting lists at all centers. We can only hope that this was transitory, and that next year will see a return to the earlier pattern.

The future of simultaneous heart-lung transplants is still unclear and this procedure has yet to establish itself fully. Few teams perform heart-lung transplants and few procedures are carried out each year. Last year, only 3 such operations were performed in Spain and the peak year was 1998 with 7 heart-lung transplantations. Technical difficulties, the so-called "consumption" of organs and the substantially worse associated prognosis make development of this type of transplant complicated. Of the other simultaneous transplantation procedures, most progress has been made with heart-kidney transplant. Although the volume is low, the prognosis is clearly better than that for heart-lung transplantations.

For years, ischemic heart disease has been the most frequent indication for heart transplantation in Spain, which is not surprising given the prevalence of the disease. Some international registries report dilated cardiomyopathy as the most frequent indication but this may be a terminological issue as ischemic heart disease accompanied by substantial ventricular dilation is defined as dilated cardiomyopathy.

The importance of waiting list mortality may be underestimated as it only includes those patients who die while on the list and ignores those removed due to severe decompensation with multiple organ failure and who subsequently die. In 2003, the number of patients who died and the number removed from the waiting list were similar to previous years (9% and 22%, respectively).

Urgent heart transplantations are controversial because they are operations with specific characteristics (recipients in poor clinical condition and donors who are often less than ideal; longer periods of ischemia) that entail a worse prognosis than programmed transplants. Last year, the percentage of urgent transplants increased substantially (29% vs 26% in 2002). This was above the average for the last 5 years (21%). Although urgent procedures involve a higher degree of risk, the transplant teams believe they should continue to be performed given that they are the only option available for the subgroup of patients with advanced heart failure and uncontrollable acute decompensation.

Overall survival has improved steadily over the years. However, logically, the number of patients added to the Registry each year represents a relatively smaller percentage of the total. Thus, the chances of our finding substantial changes within a single year are highly remote and analysis of survival by periods is more revealing.

When evaluating our Registry and comparing it with others, we must remember that it includes all the transplants performed, and reliably portrays the status of transplantation procedures in Spain. However, the analyses are global and also include high-risk transplants (urgent transplants, older age group recipients, pediatric transplants, re-transplants, heterotopic transplantations, heart-lung, heart-kidney, heart-liver, and other simultaneous transplantations).

Early mortality (death within 30 days post-transplant) was 13% last year, similar to the previous 5 years, although 2002 had seen a reduction to 10%. The most frequent cause of early mortality was acute graft failure, causing 45% of early deaths. The impact of this complication is so great that, despite being a postoperative problem, it accounts for a substantial percentage (19%) of all deaths after the first month. It is worth noting that mortality due to rejection (early mortality, 7%, late mortality, 9%) is somewhat lower than that caused by infection (early mortality, 14%, late mortality, 18%). Perhaps transplant teams should consider reducing immunosuppression regimens even though this might increase the number of rejection episodes.

To conclude, we can say that:

1. The annual volume of heart transplantations has fallen over recent years.

2. The practice of combined heart-lung transplantation procedures has yet to become established in Spain.

3. General survival rates are above those recorded in many international registry reports and have shown a year-on-year improvement especially in the last 5 years.

4. We must continue our efforts to reduce the high incidence of acute graft failure. This would have a substantial positive effect on early and overall survival.

Correspondence: Dr. L. Almenar Bonet.

Avda. Primado Reig, 189-37. 46020 Valencia. España.

E-mail: lu.almenarb5@comv.es