We describe the results for Spain of the Second European Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Survey (CRT-Survey II) and compare them with those of the other participating countries.

MethodsWe included patients undergoing CRT device implantation between October 2015 and December 2016 in 36 participating Spanish centers. We registered the patients’ baseline characteristics, implant procedure data, and short-term follow-up information until hospital discharge.

ResultsImplant success was achieved in 95.9%. The median [interquartile range] annual implantation rate by center was significantly lower in Spain than in the other participating countries: 30 implants/y [21-50] vs 55 implants/y [33-100]; P=.00003. In Spanish centers, there was a lower proportion of patients ≥ 75 years (27.9% vs 32.4%; P=.0071), a higher proportion in New York Heart Association functional class II (46.9% vs 36.9%; P <.00001), and a higher percentage with electrocardiographic criteria of left bundle branch block (82.9% vs 74.6%; P <.00001). The mean length of hospital stay was significantly lower in Spanish centers (5.8±8.5 days vs 6.4±11.6; P <.00001). Spanish patients were more likely to receive a quadripolar LV lead (74% vs 56%; P <.00001) and to be followed up by remote monitoring (55.8% vs 27.7%; P <.00001).

ConclusionsThe CRT-Survey II shows that, compared with other participating countries, fewer patients in Spain aged ≥ 75 years received a CRT device, while more patients were in New York Heart Association functional class II and had left bundle branch block. In addition, the length of hospital stay was shorter, and there was greater use of quadripolar LV leads and remote CRT monitoring.

Keywords

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in adequately selected patients with symptomatic heart failure, reduced ejection fraction, and wide QRS.1–7 For this reason, clinical guidelines issued in Europe and other countries describe the indications for this therapy based on solid evidence and high levels of recommendation.8–11

The available scientific evidence on CRT comes from randomized clinical trials, observational studies, and registries. Randomized clinical trials have been designed to answer specific questions, which are clearly defined in their protocols, and have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, the results of these studies are only applicable to the population specifically included in each study. In contrast, data from registries and surveys represent daily clinical practice and offer a real-world picture of the use and benefit of a particular medication or device.12

The first European Society of Cardiology (ESC) cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) survey (CRT-Survey I) was conducted from 2008 to 2009 in 13 member countries of the ESC. The results showed that CRT was being applied in a very broad range of the population, which had not been adequately represented in the randomized clinical trials published until that time.13 This population, which was poorly represented in the large clinical trials, included patients aged 75 years or more, patients with a narrow QRS, patients with atrial fibrillation, and patients whose conventional pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator had been upgraded. In addition, the CRT-Survey I found wide variations in CRT implantation practice both regionally and nationally. Since the CRT-Survey I was first published, relevant changes have been introduced in the ESC clinical practice guidelines on CRT by the Heart Failure Association (HFA) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA).8,9 Given this background, both associations decided to conduct a second edition of the ESC-CRT-Survey. The aim was to describe current clinical practice that would be useful for patients, physicians, managers, the pharmaceutical industry, and device manufacturers. We present and compare the results of the Spanish CRT-Survey II with those from the other participating countries.

METHODSSurvey design and scientific committeeThe survey was designed as a joint initiative of the HFA and the EHRA.14 The design of the CRT-Survey II and the detailed content of the electronic case report form (eCRF) have been previously published.14

Each participating country was represented by a national coordinator appointed by the president of the corresponding national society of cardiology. The national coordinator was responsible for obtaining approval from the ethics committee if needed, recruiting the participating centers, and distributing information from the scientific committee to all participants. In the case of Spain, 54 hospitals were invited to participate, of which 36 actively participated in the survey and included at least 1 patient.

Study population and patient inclusion periodThe study included any patient selected for implantation with a CRT pacemaker (CRT-P) or CRT defibrillator (CRT-D) in any of the 36 participating Spanish hospitals. Patients were included regardless of procedural success. We included primary implants and upgrading procedures from a previous pacemaker or a previous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. We excluded generator replacement and surgical revisions of previously implanted devices because the survey was designed to include only the implantation of new CRT devices.

The patient inclusion period was initially planned to last 9 months. The first patient was included on October 1, 2015. Subsequently, the scientific committee decided to extend the inclusion period by 6 months to December 31, 2016, with the aim of increasing the size of the sample in order to increase its representativeness and thus enable comparisons between the participating countries.

Hospital questionnaireEach of the participating centers completed a questionnaire on its characteristics, such as the size of the hospital (number of beds), the type of center (public/private/university), the catchment population, the operator's degree of specialization, infrastructures, and the routine CRT device implantation protocol used.14

Electronic case report formThe participating centers were asked to include patients who were scheduled to receive a CRT device and to complete an electronic case report form (eCRF) for each patient. The eCRF collected information on patient characteristics, complementary tests performed, indication for CRT, implant procedure, and a short-term follow-up that included adverse events and complications until hospital discharge.14 No data were recorded on longer-term follow-up. The anonymity of the participating patients was ensured at all times. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Trials Committee of the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe de Valencia.

Data collection and processingThe eCRF, data processing, and statistical analyses were conducted by the Institut für Herzinfarktforschung.15 The daily operational control of the progress of the survey was conducted at Stavanger University Hospital, University of Bergen, Norway.

Continuous variables are expressed as medians [interquartile range]. Discrete variables are expressed as percentages. Data obtained by the Spanish centers and the participating centers were compared using the Student t test for continuous variables and the chi square test for discrete variables. A P value of ≤ .05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance.

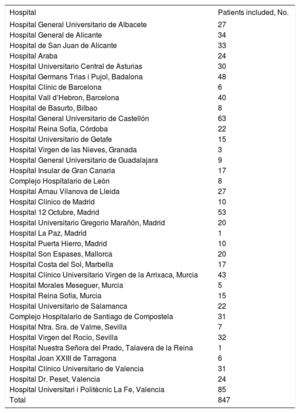

RESULTSThe CRT-Survey II included 11 088 patients from 42 countries belonging to the ESC (Table 1). In Spain, the study included 847 patients from the 36 participating hospitals (Table 2). The representativeness of the survey was estimated using data on implants in each country according to the EHRA white paper. Thus, the survey collected information on 20.1% of all predicted CRT implants in Spain during the inclusion period.

Participating countries and number of patients included

| Country | Patients included, No. |

|---|---|

| Germany | 675 |

| Algeria | 66 |

| Armenia | 2 |

| Austria | 407 |

| Belgium | 262 |

| Bulgaria | 264 |

| Croatia | 115 |

| Czech Republic | 931 |

| Denmark | 254 |

| Egypt | 22 |

| Slovakia | 472 |

| Slovenia | 119 |

| Spain | 847 |

| Estonia | 58 |

| Finland | 351 |

| France | 754 |

| Georgia | 24 |

| Greece | 137 |

| Hungary | 467 |

| Iceland | 19 |

| Ireland | 85 |

| Israel | 39 |

| Italy | 526 |

| Kazakhstan | 34 |

| Latvia | 79 |

| Lebanon | 30 |

| Lithuania | 173 |

| Luxembourg | 36 |

| Macedonia | 70 |

| Malta | 26 |

| Montenegro | 6 |

| Morocco | 12 |

| Netherlands | 202 |

| Norway | 370 |

| Poland | 1241 |

| Portugal | 58 |

| UK | 571 |

| Romania | 214 |

| Russia | 71 |

| Sweden | 255 |

| Switzerland | 320 |

| Turkey | 424 |

| Total | 11 088 |

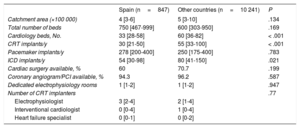

Spanish centers participating in the crt-survey ii and number of patients included by center

| Hospital | Patients included, No. |

|---|---|

| Hospital General Universitario de Albacete | 27 |

| Hospital General de Alicante | 34 |

| Hospital de San Juan de Alicante | 33 |

| Hospital Araba | 24 |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias | 30 |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona | 48 |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona | 6 |

| Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | 40 |

| Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao | 8 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Castellón | 63 |

| Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba | 22 |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | 15 |

| Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada | 3 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara | 9 |

| Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria | 17 |

| Complejo Hospitalario de León | 8 |

| Hospital Arnau Vilanova de Lleida | 27 |

| Hospital Clínico de Madrid | 10 |

| Hospital 12 Octubre, Madrid | 53 |

| Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid | 20 |

| Hospital La Paz, Madrid | 1 |

| Hospital Puerta Hierro, Madrid | 10 |

| Hospital Son Espases, Mallorca | 20 |

| Hospital Costa del Sol, Marbella | 17 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia | 43 |

| Hospital Morales Meseguer, Murcia | 5 |

| Hospital Reina Sofía, Murcia | 15 |

| Hospital Universitario de Salamanca | 22 |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Santiago de Compostela | 31 |

| Hospital Ntra. Sra. de Valme, Sevilla | 7 |

| Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | 32 |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado, Talavera de la Reina | 1 |

| Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona | 6 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | 31 |

| Hospital Dr. Peset, Valencia | 24 |

| Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe, Valencia | 85 |

| Total | 847 |

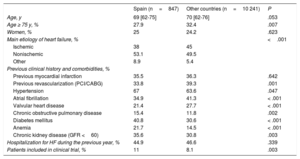

The median number of annual CRT implants reported by the 36 Spanish centers was 30 [21-50], which was significantly less than the median of 55 [33-100] reported by the other participating countries (P < .001) (Table 3). Most of the participating Spanish centers were university hospitals (94.3%), whereas in the other countries there was broad representation of nonuniversity teaching hospitals (25.9%) and private hospitals (8.8%).

Characteristics of the participating hospitals

| Spain (n=847) | Other countries (n=10 241) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catchment area (×100 000) | 4 [3-6] | 5 [3-10] | .134 |

| Total number of beds | 750 [467-999] | 600 [303-950] | .169 |

| Cardiology beds, No. | 33 [28-58] | 60 [36-82] | < .001 |

| CRT implants/y | 30 [21-50] | 55 [33-100] | < .001 |

| Pacemaker implants/y | 278 [200-400] | 250 [175-400] | .783 |

| ICD implants/y | 54 [30-98] | 80 [41-150] | .021 |

| Cardiac surgery available, % | 60 | 70.7 | .199 |

| Coronary angiogram/PCI available, % | 94.3 | 96.2 | .587 |

| Dedicated electrophysiology rooms | 1 [1-2] | 1 [1-2] | .947 |

| Number of CRT implanters | .77 | ||

| Electrophysiologist | 3 [2-4] | 2 [1-4] | |

| Interventional cardiologist | 0 [0-4] | 1 [0-4] | |

| Heart failure specialist | 0 [0-1] | 0 [0-2] | |

CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed as median [interquartile range].

In Spain, the median age of the study patients was 69 [62-75] years, which was similar to the other patients (70 [62-76] years) (Table 4). There was a lower percentage of patients aged 75 years or more in Spanish centers (27.9%) than in the other centers (32.4%; P=.007). There was a very similar percentage of implants in men and women: 75% and 25% in Spanish centers, respectively, and 75.8% and 24.2% in the other centers, respectively. The percentage of implants conducted via scheduled admission was lower in Spain than in the other countries (68.8% vs 77.6%; P < .001). However, the number of patients included in clinical trials was higher in Spain (11.0% vs 8.1%; P=.003). The type of heart disease underlying the need for implantation significantly differed between Spain and the other countries, with a lower percentage of patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (38% vs 45%), and a higher percentage of patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (NICM) (53.1% vs 49.5%) or with other etiologies of heart failure (8.9% vs 5.4%; P < .001).

Patients’ demographic characteristics

| Spain (n=847) | Other countries (n=10 241) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 69 [62-75] | 70 [62-76] | .053 |

| Age ≥ 75 y, % | 27.9 | 32.4 | .007 |

| Women, % | 25 | 24.2 | .623 |

| Main etiology of heart failure, % | <.001 | ||

| Ischemic | 38 | 45 | |

| Nonischemic | 53.1 | 49.5 | |

| Other | 8.9 | 5.4 | |

| Previous clinical history and comorbidities, % | |||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 35.5 | 36.3 | .642 |

| Previous revascularization (PCI/CABG) | 33.8 | 39.3 | .001 |

| Hypertension | 67 | 63.6 | .047 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 34.9 | 41.3 | < .001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 21.4 | 27.7 | < .001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15.4 | 11.8 | .002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40.8 | 30.6 | < .001 |

| Anemia | 21.7 | 14.5 | < .001 |

| Chronic kidney disease (GFR <60) | 35.6 | 30.8 | .003 |

| Hospitalization for HF during the previous year, % | 44.9 | 46.6 | .339 |

| Patients included in clinical trial, % | 11 | 8.1 | .003 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Values are expressed as percentage or median [interquartile range].

In addition, a smaller percentage of patients had a history of atrial fibrillation (34.9% vs 41.3%; P < .001) and valvular disease (21.4% vs 27.7%; P < .001) (Table 4). However, other comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, anemia, and kidney disease were more common in the patients included in the Spanish centers. In total, 26.1% of all implants were upgrading procedures in patients who already had a device.

Clinical assessment prior to implantationMost patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II (46.9%) or III (47.5%) (Table 5). In contrast to the other countries, a greater percentage of Spanish patients were in class II (46.9% vs 36.9%; P < .001), whereas the percentage of Spanish patients in class IV was negligible (0.7% vs 4.8%; P < .001).

Clinical assessment prior to implantation

| Spain (n=847) | Other countries (n=10 241) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NYHA functional class, % | < .001 | ||

| I | 4.9 | 3.3 | |

| II | 46.9 | 36.9 | |

| III | 47.5 | 55.1 | |

| IV | 0.7 | 4.8 | |

| BMI | 28 [25-31] | 27 [25-31] | .167 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 122 [110-135] | 122 [110-137] | .154 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70 [61-79] | 72 [67-80] | < .001 |

| Analytical parameters (most recent) | |||

| BNP, pg/mL | 619 [205-1.105] | 420 [149-1.115] | .257 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 2469 [978-5250] | 2400 [1070-5523] | .667 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1 [1-2] | 1 [1-1] | .309 |

| Hb, g/dL | 13 [12-14] | 13 [12-15] | < .001 |

| ECG before implantation | |||

| Heart rate, bpm | 70 [60-79] | 70 [61-80] | < .001 |

| Atrial rhythm, % | .023 | ||

| Sinus | 72.6 | 68.9 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23.1 | 25.9 | |

| Atrial paced rhythm | 2.2 | 2.9 | |

| Other | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| PR interval, ms | 180 [160-210] | 180 [160-210] | .877 |

| AV block II/III, % | 22.9 | 18.6 | .002 |

| Pacemaker-dependent, % | 15.8 | 13.9 | .128 |

| QRS morphology, % | < .001 | ||

| Left bundle branch block | 81.7 | 72 | |

| Right bundle branch block | 8.9 | 6.4 | |

| Other | 9.4 | 21.6 | |

| QRS duration, ms | 160 [145-174] | 160 [140-174] | .020 |

| <120ms, % | 3.7 | 7.8 | |

| 120-129ms, % | 4 | 5.4 | |

| 130-149ms, % | 19.3 | 18.6 | |

| 150-179ms, % | 51.3 | 46.7 | |

| > 180ms, % | 21.7 | 21.5 | |

| Clinical indication for CRT, % | |||

| HF with wide QRS | 55 | 60.4 | .002 |

| HF or LV dysfunction and indication for ICD | 50.2 | 47.7 | .152 |

| Indication for PM and high percentage of predicted RV stimulation | 24.8 | 22.7 | .166 |

| Evidence of mechanical asynchrony | 8.4 | 11.8 | .002 |

| Other | 2.5 | 4.6 | .004 |

| LVEF, % | 29 [24-34] | 29 [23-34] | .145 |

| LVEF <25% | 26.9 | 27.6 | |

| LVEF 25-35% | 59.2 | 59.5 | |

| LVEF > 35% | 13.9 | 12.9 | |

| LVEDD, mm | 62 [57-68] | 63 [58-69] | .002 |

| Mitral regurgitation, % | .478 | ||

| Mild | 44 | 46.7 | |

| Moderate | 25.3 | 26.6 | |

| Severe | 8 | 6.8 | |

| None | 22.7 | 20 | |

BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ECG, electrocardiogram; Hb, hemoglobin; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LV, left ventricle; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PM, pacemaker; RV, right ventricle.

Values are expressed as percentage or median [interquartile range].

At the time of implantation, 72.6% of the Spanish patients were in sinus rhythm; the percentage of Spanish patients with atrial fibrillation was slightly lower than that of patients in the other countries, although without reaching statistical significance (23.1% vs 25.9%; P=.078). Mean QRS duration was 159 ± 24ms. In total, 73% of Spanish patients had a QRS equal to or greater than 150ms and 19.3% had a QRS of 130ms to 150ms. These values are similar to those of the other countries. There was a greater percentage of complete left bundle branch block (LBBB) (81.7% vs 72%; P < .001) and complete right bundle branch block (RBBB) (8.9% vs 6.4%; P=.005) (Table 5) in Spanish patients than in the other patients.

In total, 23.3% of the Spanish patients had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than or equal to 35%, and 33% had at least moderate mitral regurgitation. The most frequent indication for CRT implantation was heart failure and wide QRS (55% of patients). In total, 55% of patients had heart failure, severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and indication for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. In 24.8% of patients, the only reason for implantation was the need for stimulation and a predicted high percentage of stimulation.

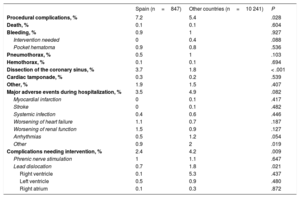

Implant-related parametersIn Spain, the implant success rate was 95.9% (Table 6). In contrast to the other countries, implants were mainly performed by electrophysiologists (92.9% vs 75.7%; P < .001). The number of unsuccessful implants was significantly higher in Spain (4.1% vs 2.6%; P=.009). In total, the percentages of Spanish patients with CRT-D (68.8%) and CRT-P (31.2%) were similar to those of the other countries. More CRT-Ds than CRT-Ps (80.1% vs 19.9%) were implanted in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy than in patients with NICM (64.7% and 35.3% respectively; P < .001). A higher percentage of CRT-Ps than CRT-Ds (58.5% vs 41.5%) were implanted in patients whose indication was the need for stimulation or a predicted high percentage of stimulation. In Spain, the median duration of the implantation procedure was significantly higher than the mean (120 [90-150] minutes vs 90 [65-120] minutes; P < .001). In total, 11.4% of LV leads were surgically implanted in the epicardium. Multipolar LV leads were used in 74.2% of patients; this percentage was much higher than that registered in the other countries. The LV lead was in lateral segment locations in 86.7% of patients and in medial segment locations in 72.9% of patients. The periprocedural complication rate was 7.2%, which was significantly higher than the mean of 5.4% reported by the other participating countries (P=.028) (Table 7).

Implant-related parameters

| Spain (n=847) | Other countries (n=10 241) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheduled admission, % | 68.8 | 77.6 | < .001 |

| Referred from another center, % | 24.4 | 25.4 | .537 |

| Time from admission to implantation, d | 1 [1-4] | 1 [1-4] | .017 |

| Implant success, % | 95.9 | 97.4 | .009 |

| Implant failure, % | 4.1 | 2.6 | .009 |

| Device type, % | .531 | ||

| CRT-P | 31.2 | 30.2 | |

| CRT-D | 68.8 | 69.8 | |

| Implanters, % | < .001 | ||

| Electrophysiologist | 92.9 | 75.7 | |

| HF specialist | 0.5 | 5.4 | |

| Interventional cardiologist | 3.7 | 13 | |

| Surgeon | 2.1 | 4.5 | |

| Other | 0.9 | 1.4 | |

| Duration, min | 120 [90-150] | 90 [65-120] | < .001 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 16 [9-28] | 13 [8-22] | < .001 |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis, % | 99.6 | 98.6 | .011 |

| Defibrillation test, % | 1.1 | 5.1 | < .001 |

| First lead implanted, % | < .001 | ||

| RV | 91.4 | 82.9 | |

| LV | 8.6 | 17.1 | |

| RV lead location, % | < .001 | ||

| Apical | 81.5 | 59.6 | |

| Septal | 16 | 38.1 | |

| RVOT | 2.6 | 2.3 | |

| LV lead implant success, % | 99.3 | 99.4 | .522 |

| Lead implanted via epicardial route, % | 11.5 | 8.8 | .011 |

| Type of LV lead, % | < .001 | ||

| Unipolar | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| Bipolar | 25 | 43.7 | |

| Multipolar | 74.3 | 55.6 | |

| Coronary venography, % | 90.4 | 91.6 | .226 |

| Venography with occlusion, % | 58.2 | 46.2 | < .001 |

| Dilatation of the coronary vein, % | 1.2 | 2.5 | .025 |

| Checking phrenic nerve stimulation, % | 94.1 | 90.1 | < .001 |

| Assessment of the position of the LV lead, % | 98.6 | 97.3 | .001 |

| Dual-plane view | 92.6 | 87.8 | |

| Single-plane LAO | 6.8 | 11.5 | |

| Single-plane RAO | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| Position in LAO projection, % | .645 | ||

| Lateral | 86.7 | 83.9 | |

| Posterior | 10 | 11.7 | |

| Anterior | 3.3 | 4.4 | |

| Position in RAO projection, % | |||

| Medial | 72.9 | 71 | |

| Basal | 13 | 15 | |

| Apical | 14.1 | 14 | |

| Optimization of the LV lead position, % | 17.7 | 35.2 | < .001 |

CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with implantable automatic defibrillator; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker; LAO, left anterior oblique; LV, left ventricle; RAO, right anterior oblique; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed as median [interquartile range].

Procedural complications and complications before hospital discharge

| Spain (n=847) | Other countries (n=10 241) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural complications, % | 7.2 | 5.4 | .028 |

| Death, % | 0.1 | 0.1 | .604 |

| Bleeding, % | 0.9 | 1 | .927 |

| Intervention needed | 0 | 0.4 | .088 |

| Pocket hematoma | 0.9 | 0.8 | .536 |

| Pneumothorax, % | 0.5 | 1 | .103 |

| Hemothorax, % | 0.1 | 0.1 | .694 |

| Dissection of the coronary sinus, % | 3.7 | 1.8 | < .001 |

| Cardiac tamponade, % | 0.3 | 0.2 | .539 |

| Other, % | 1.9 | 1.5 | .407 |

| Major adverse events during hospitalization, % | 3.5 | 4.9 | .082 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0.1 | .417 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0.1 | .482 |

| Systemic infection | 0.4 | 0.6 | .446 |

| Worsening of heart failure | 1.1 | 0.7 | .187 |

| Worsening of renal function | 1.5 | 0.9 | .127 |

| Arrhythmias | 0.5 | 1.2 | .054 |

| Other | 0.9 | 2 | .019 |

| Complications needing intervention, % | 2.4 | 4.2 | .009 |

| Phrenic nerve stimulation | 1 | 1.1 | .647 |

| Lead dislocation | 0.7 | 1.8 | .021 |

| Right ventricle | 0.1 | 5.3 | .437 |

| Left ventricle | 0.5 | 0.9 | .480 |

| Right atrium | 0.1 | 0.3 | .872 |

Median hospital stay was significantly lower in Spain than in the other countries: 2 [2-7] vs 3 [2-7] days (P < .001) (Table 8). The major adverse event rate during hospitalization was 3.5%, including a mortality rate of 0.4%. Before hospital discharge, AV and VV intervals were reprogrammed using device-specific software in 35% of patients. In 98% of patients, postimplant follow-up was performed in the same implantation center. In total, 55.8% of the patients were followed up by remote monitoring; this percentage was significantly higher than that in the other countries (27.7%; P < .001).

Postimplantation parameters

| Spain (n=847) | Other countries (n=10 241) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECG postimplantation | |||

| Stimulated QRS, ms | 134 [120-146] | 138 [120-152] | .013 |

| Device programming | |||

| AV interval programmed before discharge | 63.8 | 57.4 | < .001 |

| VV interval programmed before discharge | 64.1 | 55.7 | < .001 |

| AV and VV optimization using device software | 35 | 36.5 | .888 |

| Status at time of discharge, % | .447 | ||

| Alive | 99.8 | 99.6 | |

| Dead | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Total hospital stay, d | 2 [2-7] | 3 [2-7] | < .001 |

| Planning follow-up, % | |||

| Implant center | 97.8 | 85.4 | < .001 |

| Other hospital | 1.9 | 8.6 | < .001 |

| Cardiologist in private clinic | 0.2 | 5.7 | < .001 |

| Primary care physician | 0.4 | 0.9 | .110 |

| CRT/PM unit | 11.8 | 10.3 | .159 |

| HF unit | 6 | 2.2 | < .001 |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.3 | .695 |

| Pharmacological treatment at discharge, % | |||

| Loop diuretics | 81 | 81.1 | .989 |

| ACEI/ARB | 87.5 | 86.3 | .359 |

| Antimineralocorticoid | 70.2 | 62.6 | < .001 |

| Beta-blockers | 87.5 | 89.1 | 0.165 |

| Ivabradine | 13.6 | 4.9 | < .001 |

| Digoxin | 9.1 | 10.5 | .205 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 7.1 | 9.1 | .047 |

| Amiodarone | 16 | 17.4 | .302 |

| Other antiarrhythmic agents | 0.7 | 1.8 | .024 |

| Oral anticoagulation | 43.6 | 46.8 | .069 |

| Vitamin K antagonists (warfarin/acenocoumarol) | 81.9 | 69.4 | < .001 |

| Dabigatran | 3.6 | 6.9 | .017 |

| Rivaroxaban | 5.6 | 12.9 | < .001 |

| Apixaban | 8.4 | 10.5 | .202 |

| Edoxaban | 0.6 | 0.4 | .531 |

| Antiplatelet drugs, % | 42.3 | 43.8 | .379 |

| Aspirin | 39.3 | 41.5 | .221 |

| Clopidogrel | 10 | 12.6 | .030 |

| Ticagrelor | 1.5 | 1.3 | .652 |

| Prasugrel | 0.9 | 0.2 | .002 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; AV, atrioventricular; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; HF, heart failure; PM, pacemaker; VV, interventricular.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed as median [interquartile range].

The CRT-Survey II provides a real-world picture of the type of patients who are actually receiving a CRT device in Spain. The survey goes beyond the profiles provided by large clinical trials or clinical practice guidelines.

In line with data published by Eucomed, the EHRA, and Spanish pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registries,16–19 the CRT device implantation rate in Spanish hospitals was significantly lower than the mean implantation rate in the other participating countries. The median age of patients who received a CRT device was around 70 years, less than 30% were older than 75 years (in contrast to those from the other countries), and only 1 in 4 implants were performed in women. In Spain and the other countries, the main etiology underlying the need for CRT implantation was NICM. However, it is worth noting that a significantly higher percentage of Spanish patients had NICM than dilated ischemic cardiomyopathy compared with the other countries. The explanation could be that, given the lower total implant rate in Spain, implants are carefully selected. Therefore, implants would be favored in those patients who have been shown to obtain the greatest benefit from CRT, as is the case of patients with NICM.20 Consistent with this argument, the vast majority of Spanish patients who received a CRT device were in NYHA functional class II and III, whereas the number of patients in NYHA functional class IV was negligible (0.7%).

As recommended in the guidelines,8,9 patient selection was based on QRS morphology and width: nearly 83% of the patients included in Spanish centers had LBBB in the baseline electrocardiogram. This percentage was significantly higher than that in other participating countries. Similarly, 73% of patients had a QRS width equal to or greater than 150ms, and only 7.7% had a QRS width of less than 130ms. In both cases, the percentages were significantly higher in Spain than those of the other participating countries, which suggests that candidate selection for CRT might be better in Spain than in the other countries. However, implantation is still performed in patients with RBBB (up to 8.8%), even though published data indicate the lack of efficacy of CRT in this patient subgroup.21 Likewise, up to 14% of the Spanish patients had an LVEF greater than 35%, although it is very likely that a large part of this percentage comprised patients with an indication for permanent stimulation whose reduced LVEF led to the implantation of an LV stimulation lead. It is striking that only 25% of implants were performed in women because it is known that a higher percentage of women with heart failure and reduced LVEF have LBBB, and that women with LBBB benefitted from CRT at a shorter QRS duration than men with LBBB.22,23

Regarding technical aspects, a high success rate was achieved with CRT implantation (96.3%) and LV lead implantation (99.3%). It is noteworthy that up to 11.4% of the leads were implanted in the epicardium, although the survey did not collect information on the reasons for this approach. This large percentage was probably due to the inclusion of patients with previous failure of the transvenous route, as well as to the inclusion of other patients with an indication for CRT who had received an LV lead during concomitant cardiac surgery. Another novel finding of the survey was the widespread use of quadrupole leads, which already comprise almost 75% of the total number of LV leads implanted in Spanish centers. This percentage is much higher than that in the other participating centers. However, the survey did not gather information on whether the implanted generators had multipoint stimulation or whether they were activated in the implant.

It is also noteworthy that the periprocedural complication rate was significantly higher in Spanish centers than in the other centers. However, analysis of the causes of these complications shows that the difference was due to a higher rate of coronary sinus dissection (50% of all periprocedural complications in Spanish centers vs 32.6% in the other countries). In general, coronary sinus dissection is a complication that does not typically lead to severe repercussions for the patient and does not even prevent LV lead implantation in most patients.24 On the other hand, the rate of other complications was similar in Spain and the other countries, but there was a significantly lower rate of pneumothorax in Spain (0.46% vs 1.06%; P=.011). The periprocedural mortality rate was very low (0.11% in Spanish centers), and other severe complications, such as cardiac tamponade, were observed in only 0.23% of patients. The periprocedural complication rate reported in other large published series, such as a US registry that included more than 439 000 inpatients who received an CRT device,25 was similar to the 7% reported in Spain.

LimitationsThis study is limited by its use of a survey format, which only collects pre-established data from the time of implantation to the time of hospital discharge. Therefore, the validity of the data on complications and morbidity and mortality may be limited by their being underestimated due to the lack of patient follow-up. In addition, only 20.1% of the total number of predicted CRT implants were collected by the survey during the inclusion period and therefore the data obtained may not reflect the current situation in Spain. More extensive surveys could be conducted to confirm these findings.

CONCLUSIONSThe results of the CRT-Survey II provide a clear picture of the current use of this therapy in Spain. The results show a high rate of implant success (96.3%). In Spanish hospitals, there was a lower percentage of patients aged 75 years or older, and a higher percentage of patients in NYHA functional class II with LBBB, remote monitoring, and significantly shorter hospital stays.

FUNDINGThis study received funding from the EHRA, the HFA, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Sorin, St Jude Medical, Abbott, Bayer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and Servier.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTDuring the course of this study, K. Dickstein received grants from the HFA, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Sorin, St Jude Medical, Abbott, Bayer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Servier, and the EHRA. C. Normand received scholarships from the HFA, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Sorin, St Jude Medical, Abbott, Bayer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Servier, and the EHRA. C. Linde received research grants from Astra through the Karolinska Institutet Stockholm (Sweden), and fees for articles unrelated to the present article from Vifor, Novartis, Medtronic, and Abbot. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- –

CRT reduces the morbidity and mortality of patients with heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, wide QRS, and optimal pharmacological treatment.

- –

Clinical practice guidelines have established the key indications for CRT based on the results of large randomized clinical trials.

- –

The CRT-Survey II survey provides a clear picture of the use of CRT in Europe.

- –

These data reflect current clinical practice, unlike those obtained from large randomized trials.

- –

The Spanish results help identify the characteristics of the patients who have received a CRT device, the approach followed, and the short-term outcomes.

- –

The survey allowed comparison of the Spanish results with those of the other countries participating in the CRT-Survey II.

The authors would like to acknowledge the operations coordinator of the CRT-Survey II survey, Tessa Baak, for her assistance in data collection and manuscript preparation. We also acknowledge the Institut für Herzinfarktforschung for its assistance in data processing and statistical analysis.