Two articles appear in this issue of the Revista Española de Cardiología dealing with the ambulatory follow-up of patients with heart failure. Both concern descriptive registries which provide up-to-date information concerning the manner of treatment of patients with heart failure. The first of these registries,1 the BADAPIC Registry (an acronym for Base de Datos en Pacientes con Insuficiencia Cardiaca--database of patients with heart failure) included patients with heart failure who were selected according to several different criteria, which hinders interpretation of the findings (the criteria for heart failure were defined but not the criteria for inclusion or exclusion to the unit or the particular clinic). The value of the registry lies in the heterogeneousness of the heart failure units or clinics. In some cases they were simple outpatient clinics, either with cardiologists or with specialists in internal medicine, whereas others were more complex, organized units staffed by personnel from different specialties who followed more elaborate health care protocols, occasionally including nurses and home visits.

The second registry examined the data from 1252 outpatients with heart failure who were seen by 465 cardiologists on one particular day in France, Germany, and Spain.2 The demographic characteristics and the treatment given to the patients were compared between the three countries. Of particular interest was the specialty of the health care professional in charge of the ambulatory follow-up of patients with heart failure (presumably the person responsible for the treatment of heart failure): the person in charge was the cardiologist alone in 46% of the patients (64% in France, 52% in Spain, and 29% in Germany) and the general physician alone in 32% of the patients, with the responsibility being shared between the cardiologist and the general physician in 16% of the patients.

The real questions arising from both studies are who can and should manage patients with heart failure and what type of organization is the most suitable. No definitive answer to these questions exists, although the possibilities being considered include the following:

1. The cardiologist is in charge of patients with heart failure.3 The main idea of medical specialization is to distribute the authority and responsibility. To this extent the situation is quite clear; heart failure is the result of failure of the function of the heart and it is thus the specialist in cardiology who is responsible for the correct care of patients with this disease. The argument most often cited by cardiologists against this proposal is that not enough cardiologists are available to care for the high number of patients with heart failure. The solution seems simple: the number of specialists required is determined by the prevalence of patients with the disease to be treated. If sufficient cardiologists are not available, then the various cardiology societies should acquaint the health care authorities with the problem, and the health care authorities should act accordingly.

2. The internal medicine specialist and the family physician assume responsibility for the care of patients with heart failure.4 The main arguments in favor of this proposal are the high number of coexisting diseases in patients with heart failure, the experience acquired in a disease which does in fact form part of internal medicine, the apathy of some cardiology teams and the opportunity for the patients to have easier, faster and more frequent access to outpatient clinics (and even to hospital beds).

3. Heart failure clinics1 are an attempt to solve the problem of the chronic ambulatory care of patients with heart failure. In their simplest form they are an example of the willingness to organize this care, though generally with no clear institutional support. At a higher degree of organization they establish protocols for the follow-up of patients and co-ordination with other health care specialists.

4. Heart failure units.5-7 Heart failure is a complicated process and the patient with heart failure requires varying degrees of medical and health care given by many specialists, depending on the patient and the course of the disease. These specialists include cardiologists, specialists in internal medicine, primary health care physicians, intensive care specialists, emergency service physicians, surgeons, nurses, and social workers. All these persons have their own particular importance, and co-ordination among them all is, to say the least, common sense. The definition of a heart failure unit is still being developed, but the unit should include cardiologists, primary care physicians or specialists in internal medicine, and nurses. These persons should provide very close protocolized control of the patient and a type of care that is more social than just scientific and medical. The benefit of this type of unit, in select patients, seems to be related with a better disease evolution, at least with a reduction in medium-term hospital admissions.5,6 The organization of heart failure units requires the explicit collaboration of the health care authorities, due to the required special recruitment of personnel and their novel functions in some medical settings (specialized home care, patient and family education, new nursing responsibilities, new social care requirements, etc). The Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology supports the formation of these units,7 and has offered to collaborate with all interested groups, which it is attempting to bring together to achieve a better degree of communication and an easier progress in setting up and developing heart failure units.

5. Heart failure specialists.8 Superspecialization, or more correctly subspecialization, is the natural evolution in medicine in response to the increased prevalence of a disease and to the rapid increase in the complexity of diagnostic methods and treatment. Both of these conditions exist in heart failure. At the current time the problem is not just the rapid incorporation of conventional pharmacological drug therapy. The diagnosis and adequate treatment of the underlying heart disease (including myocardial ischemia), as well as the correct identification of candidates for therapy by resynchronization, defibrillators, mechanical circulatory assistance, heart transplant and, in the future, gene therapy, together with the relevant patient follow-up, suggest the possible requirement for the accreditation of specialists in heart failure.8 It is probably too soon for this type of initiative to have sufficient backing to achieve official recognition, especially considering that cardiological subspecialties in Europe tend towards diagnostic techniques, but it does highlight the importance and the difficulty of keeping up-to-date in the different diseases.

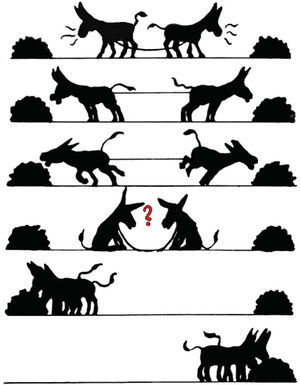

The articles by Salvador et al1 and Anguita Sánchez2 highlight once again the problem of the coordination of the different specialists caring for patients with heart failure, as well as the need for adequate continuing medical education of all specialists involved in the diagnosis and the treatment of these patients. Currently, the most intelligent response to this problem is perhaps also the most difficult, that of team work (Figure).

Figure. Team work.

See Articles on Pages 1159-69 and 1170-88

Correspondence: Dr. J. López-Sendón.

Servicio de Cardiología.

Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón.

Doctor Esquerdo, 46. 28007 Madrid. España.