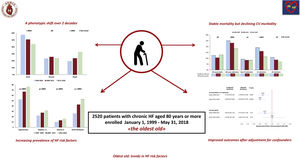

Octogenarians represent the most rapidly expanding population segment in Europe. The prevalence of heart failure (HF) in this group exceeds 10%. We assessed changes in clinical characteristics, therapy, and 1-year outcomes over 2 decades in chronic HF outpatients aged ≥ 80 years enrolled in a nationwide cardiology registry.

MethodsWe included 2520 octogenarians with baseline echocardiographic ejection fraction measurements and available 1-year follow-up, who were recruited at 138 HF outpatient clinics (21% of national hospitals with cardiology units), across 3 enrolment periods (1999-2005, 2006-2011, 2012-2018).

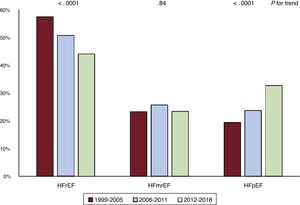

ResultsAt recruitment, over the 3 study periods, there was an increase in age, body mass index, ejection fraction, the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, pre-existing hypertension, and atrial fibrillation history. The proportion of patients with preserved ejection fraction rose from 19.4% to 32.7% (P for trend <.0001). Markers of advanced disease became less prevalent. Prescription of beta-blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists increased over time. During the 1-year follow-up, 308 patients died (12.2%) and 360 (14.3%) were admitted for cardiovascular causes; overall, 591 (23.5%) met the combined primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization. On adjusted multivariable analysis, enrolment in 2006 to 2011 (HR, 0.70; 95%CI, 0.55-0.90; P=.004) and 2012 to 2018 (HR, 0.61; 95%CI, 0.47-0.79; P=.0002) carried a lower risk of the primary outcome than recruitment in 1999 to 2005.

ConclusionsAmong octogenarians, over 2 decades, risk factor prevalence increased, management strategies improved, and survival remained stable, but the proportion hospitalized for cardiovascular causes declined. Despite increasing clinical complexity, in cardiology settings the burden of hospitalizations in the oldest old with chronic HF is declining.

Keywords

Heart failure (HF) affects over 10% of people older than 80 years.1 This population segment, the oldest old according to the World Health Organization definition, represents the most rapidly expanding group in Europe: the proportion of Europeans older than 80 years in 2019 (5.2%) is projected to rise to 7.2% by 2030.2 In our country, the percentage of octogenarians grew from 4.4% to 7.6% in the last 2 decades. In the UK, patient age and multimorbidity at first presentation of HF markedly increased from 2002 to 2015.3 In the US among octogenarians, the number of HF patients is expected to grow by 66% from 2010 to 2030.4

Elderly patients have a distinct HF phenotype, characterized by female preponderance, smaller ventricles, higher left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) values, i.e the HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) phenotype, and a higher comorbidity burden.5–9 In recent years in the general HF population a shift from HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) toward the HFpEF phenotype10,11 has been documented in parallel with the growth of obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, ie, the cardiometabolic risk factors that provide the breeding ground for HFpEF development.12 Whether similar trends also occur in the oldest old HF population has not been described.

Data on evolving prognosis in this patient group are also limited. Among elderly outpatients with chronic HF,13,14 1-year mortality, although lower than in participants hospitalized for acute HF, still exceeds 10%,15 with better survival in cardiology than in cross-discipline or primary care cohorts.

To address the scarcity of data on trends over time in clinical phenotype, treatment and prognosis of octogenarians with HF, we analyzed changes in the characteristics, drug and device therapy, 1-year all-cause mortality and hospitalizations in outpatients older than 80 years enrolled in a national chronic HF registry.

METHODSStudy design and settingIN-CHF (Italian Network on Chronic Heart Failure) is a nationwide, strictly observational multicenter registry of patients with chronic HF referred to cardiology outpatient clinics that was set up in 1995 by the Working Group on Heart Failure and by the Research Center of our scientific society.16 Standardized procedures to collect and enter data using ad hoc software were disseminated in training workshops. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating center. All patients provided informed consent for scientific use of their clinical data collected in an anonymous way.

This analysis refers to patients aged ≥ 80 years with a diagnosis of chronic HF as defined in updated European Society of Cardiology guidelines,17–21 who were recruited and followed up as outpatients at 138 HF clinics of our network. Participating units represented 21% of hospitals with cardiology units in our country, and most (59%) were located at secondary or tertiary cardiology referral centers with coronary care units and catheterization laboratory; one fourth also had cardiac surgery facilities, and 10% were academic centers. Center distribution was 51% north, 24% center, and 25% south, with a slight unbalance with respect to our geographic population distribution (46% north, 20% center, and 34% south).

Patients could be enrolled at the first presentation to the HF outpatient clinic, irrespective of disease stage or duration. Clinical management was based on the physician's judgement.

We reviewed the clinical characteristics of patients enrolled from 1 January, 1999 to 31 May, 2018, who had baseline echocardiographic documentation of LVEF and prospective follow-up data available during the first year after enrolment.

According to the time of recruitment, we divided the study period into 3 periods, corresponding approximately to the implementation in HF management of the landmark trials on beta-blockers (1999-2005) and device therapy (2006-2011) and to the clinical development of angiotensin II receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (2012-2018), respectively.

Variables and data sourcesFor each patient, demographics, clinical history (including HF symptom duration and previous hospital admissions for HF), NYHA class and primary etiology of HF were entered in the database. When multiple etiologic factors were present, the one judged by the referring cardiologist to be predominant was identified as the primary cause. Ischemic etiology of HF was defined as a history of myocardial infarction, stable or unstable angina, percutaneous coronary revascularization, or coronary artery bypass grafting. Pre-existing hypertension was defined as high blood pressure values (systolic> 140mmHg or diastolic> 90mmHg) or use of antihypertensive medications prior to HF diagnosis. Patients newly diagnosed with diabetes or on oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin were defined as diabetics. Incident HF was defined as a history of HF <6 months and no admission for HF in the previous year.

HF phenotypes were classified according to LVEF values as HFrEF (< 40%), HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF; 40%-49%) or HFpEF (≥ 50%).21

Laboratory findings were systematically collected from 2006 onward. The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula, which includes age, sex and creatinine.

HF guideline-directed medical treatment (GDMT) was defined as the daily intake of ≥ 3 guideline-recommended drugs, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASI) (including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors), beta-blockers (BB), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA). Prescription rates of HF-GDMT over time were compared in the overall population, in the subset of patients with HFrEF and in those with LVEF ≥ 40%, who had a clinical indication (pre-existing hypertension, diabetes, previous myocardial infarction) for these agents. HF-GDMT were recoded as percent of target doses22 of RASI, BB, and MRA; patients were reclassified based on achievement of ≥ 50% of the target.

Non-HF polypharmacy was defined as the daily intake of ≥ 5 drugs, excluding from the computation GDMT drugs.23

Study outcomesThe primary study endpoint was all-cause mortality or hospital admission for> 24hours (ie, overnight stay) for cardiovascular causes (). Although no provision was made for endpoint validation, specific training to standardize data collection was imparted at the beginning of the study. Data on admissions were obtained from hospital discharge codes and enquiries to primary care physicians.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are reported as number and percentages, and were compared by the chi-square test; continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations, and were compared by analysis of variance, if normally distributed, or the Kruskall-Wallis test, if not. Temporal trends were tested by the Cochran-Armitage test (binary variables), and by the Kendall Tau rank correction coefficient with the Jonkheere-Terpstra test (continuous variables).

Multivariable logistic regression on RASI prescription was performed including as covariates: estimated glomerular filtration rate (< 30; ≥ 30mL/min/1.73 m2; unknown), hyperkalemia (< 5.5; ≥ 5.5 mEq/lt, unknown), MRA and BB prescription, systolic blood pressure and LVEF; age and sex were not considered since they are included in the formula.

All patients were observed until the end of month 12 since enrolment or the occurrence of death. Cox multivariable analysis was performed to model the impact of enrolment period on the combined primary endpoint of all-cause death or cardiovascular hospitalization, whichever came first, and on the secondary endpoint of all-cause mortality, after adjustment for covariates that had been associated with prognosis in the previous literature. These included demographics (age, sex), history of HF (hypertensive, ischemic or other HF etiology, HF history> 6 months, ≥ 1 HF admission previous year), comorbidities (history of atrial fibrillation, pre-existing hypertension, diabetes, previous stroke/transient ischemic attack), clinical findings (NYHA class III-IV, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, LVEF), HF therapies (furosemide, RASI, BB, MRA, implanted cardioverter defibrillator/cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator) and non-HF polypharmacy. Moreover, in a second model, guideline-recommended drugs were considered together as the binary variable HF-GDMT.

Furthermore, patients were classified based on the intake of either HF-GDMT or non-HF polypharmacy, as a 4-entry categorical variable: neither (reference group), HF-GDMT (only), non-HF polypharmacy (only), or both. Direct adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization according to the above polypharmacy variable were obtained by a stratified Cox regression analysis. The model was adjusted for the variables that were statistically significant at a previous Cox analysis with backward selection. A simultaneous P value was obtained to test the null hypothesis of no difference among the curves.

All tests were 2-sided; a P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed with SAS system software, version 9.4.

RESULTSClinical characteristicsFrom 1999 to 2018, 2520 chronic HF patients aged ≥ 80 years were recruited in the IN-CHF Registry; 1010 (40.1%) were women. Overall, 1226 (48.7%) had HFrEF, 691 (27.4%) had HFpEF, and 603 (23.9%) had HFmrEF. As depicted in table 1, phenotype groups differed significantly in demographics and characteristics such as the prevalence of obesity, pre-existing hypertension, atrial fibrillation, ischemic etiology, and kidney dysfunction. Drug therapies, specifically neurohormonal modulators, differed. Patients with HFrEF had the worst outcome rates.

Clinical characteristics, drug and device therapy, and outcomes by phenotype

| HFrEFn=1226 | HFmrEFn=603 | HFpEFn=691 | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 83± 3 | 84±3 | 84±4 | <.0001 |

| Women | 377 (30.8) | 239 (39.6) | 394 (57.0) | <.0001 |

| Current smoker (n=1976) | 44 (4.6) | 26 (5.6) | 18 (3.3) | .31 |

| Pre-existing hypertension | 770 (62.8) | 428 (71.0) | 533 (77.1) | <.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 253 (20.6) | 145 (24.1) | 135 (19.5) | .78 |

| Diabetes | 316 (25.8) | 193 (32.0) | 200 (28.9) | .07 |

| Obesity | 121 (9.9) | 89 (14.8) | 137 (19.8) | <.0001 |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 121 (9.9) | 60 (10.0) | 69 (10.0) | .93 |

| HF history ≥ 6 mo | 849 (69.3) | 415 (68.8) | 484 (70.0) | .76 |

| ≥ 1 HF admission, previous y | 626 (51.1) | 248 (41.1) | 297 (43.0) | .0001 |

| Incident HFa | 135 (11.0) | 85 (14.1) | 74 (10.7) | .92 |

| Ischemic etiology (n=1067) | 630 (51.4) | 290 (48.1) | 147 (21.3) | <.0001 |

| NYHA IIII-IV, % | 375 (30.6) | 132 (21.9) | 192 (27.8) | .07 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 468 (38.2) | 261 (43.3) | 389 (56.3) | <.0001 |

| Left bundle branch block | 304 (24.8) | 90 (14.9) | 63 (9.1) | <.0001 |

| GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n=1365) | 107 (17.2) | 45 (14.1) | 44 (10.5) | .002 |

| Body mass index | 25.0±3.8 | 25.7±4.0 | 26.0±4.4 | <.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 125±19 | 129±20 | 130±21 | <.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure mmHg | 73±10 | 74±10 | 73±10 | .20 |

| Heart rate bpm | 72±14 | 71±13 | 72±14 | .59 |

| eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2 (n=1365) | 43.3±14.3 | 46.0±14.4 | 47.4±14.9 | <.0001 |

| LVEF, % | 30.5±5.7 | 43.0±2.8 | 57.8±6.4 | <.0001 |

| Drug therapy | ||||

| Non-HF polypharmacyb | 491 (40.1) | 232 (38.5) | 256 (37.1) | .19 |

| Furosemide | 1141 (93.1) | 527 (87.4) | 597 (86.4) | <.0001 |

| Furosemide ≥ 75 mg/d (n=1823) | 364 (41.3) | 151 (36.1) | 203 (38.8) | .27 |

| Digitalis | 293 (23.9) | 125 (20.7) | 155 (22.4) | .36 |

| Nitrates | 371 (30.3) | 163 (27.0) | 150 (21.7) | <.0001 |

| Ivabradine | 48 (3.9) | 26 (4.3) | 8 (1.2) | .003 |

| Oral anticoagulants | 467 (38.1) | 239 (39.6) | 342 (49.5) | <.0001 |

| RASI | 1014 (82.7) | 477 (79.1) | 525 (76.0) | .0003 |

| BB | 896 (73.1) | 400 (66.3) | 429 (62.1) | <.0001 |

| MRA | 666 (54.3) | 285 (47.3) | 303 (43.9) | <.0001 |

| RASI and BB | 335 (27.3) | 165 (27.4) | 187 (27.1) | .91 |

| RASI and BB and MRA | 409 (33.4) | 148 (24.5) | 132 (19.1) | <.0001 |

| Devices | ||||

| CRT-P | 22 (1.8) | 11 (1.8) | 3 (0.4) | .02 |

| CRT-D | 89 (7.3) | 19 (3.2) | 7 (1.0) | <.0001 |

| ICD | 193 (15.7) | 35 (5.8) | 12 (1.7) | <.0001 |

| 1-year outcomes | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 170 (13.9) | 73 (12.1) | 65 (9.4) | .004 |

| All-cause death or CV hospitalization | 325 (26.5) | 129 (21.4) | 137 (19.8) | .0005 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 294 (24.0) | 113 (18.7) | 122 (17.7) | .0006 |

| Non-CV hospitalization | 117 (9.5) | 47 (17.8) | 52 (7.5) | .11 |

| CV hospitalization | 202 (16.5) | 76 (12.6) | 82 (11.9) | .003 |

| HF hospitalization | 117 (9.5) | 41 (6.8) | 52 (7.5) | .08 |

BB, beta-blockers; CV, cardiovascular; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy-pacing; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NA, not available; OAC, oral anticoagulants; RASI, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

The data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Table 2 describes trends in clinical characteristics across the 3 time periods. Over time, sex distribution, smoking status, the prevalence of previous stroke/transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, left bundle branch block and the proportion of patients with incident HF did not change significantly. Conversely, in agreement with the observed phenotypic shift from HFrEF toward HFpEF (figure 1), mean age, body mass index, and LVEF gradually increased, while the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, pre-existing hypertension, and history of atrial fibrillation, as well as the proportion of ischemic patients who had undergone percutaneous/surgical revascularization, progressively increased across periods.

Changes in clinical characteristics over time

| 1999-2005n=547 | 2006-2011n=659 | 2012-2018n=1314 | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 83±3 | 84±3 | 84±3 | <.0001 |

| Women | 211 (38.6) | 270 (41.0) | 529 (40.3) | .59 |

| Current smoker (n=1976) | 10 (3.1) | 27 (5.7) | 51 (4.3) | .72 |

| Pre-existing hypertension | 286 (52.3) | 442 (67.1) | 1003 (76.3) | <.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 54 (9.9) | 131 (19.9) | 348 (26.5) | <.0001 |

| Diabetes | 120 (21.9) | 181 (27.5) | 408 (31.1) | <.0001 |

| Obesity | 53 (9.8) | 85 (13.1) | 209 (16.0) | .0003 |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 53 (9.8) | 69 (10.5) | 128 (9.7) | .93 |

| HF history ≥ 6 months | 321 (58.7) | 463 (70.3) | 964 (73.4) | <.0001 |

| ≥ 1 HF admission in previous year | 334 (61.1) | 304 (46.1) | 533 (40.6) | <.0001 |

| Incident HF* | 75 (13.7) | 74 (11.2) | 145 (11.0) | .13 |

| Ischemic etiology (n=1067) | 250 (45.7) | 292 (44.3) | 525 (40.0) | .01 |

| Ischemic, previous MI | 179 (71.6) | 238 (81.5) | 391 (74.5) | .74 |

| Ischemic, previous PCI | 40 (16.0) | 97 (33.2) | 266 (50.7) | <.0001 |

| Ischemic, previous CABG | 40 (16.0) | 79 (27.1) | 140 (26.7) | .004 |

| NYHA IIII-IV, % | 182 (33.3) | 185 (28.1) | 332 (25.3) | .0005 |

| History of atrial fibrillation % | 142 (26.0) | 282 (42.8) | 694 (52.8) | <.0001 |

| Left bundle branch block | 101 (18.5) | 122 (18.5) | 234 (17.8) | .70 |

| GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2(n=1365) | NA | 50 (14.7) | 146 (14.3) | .85 |

| Body mass index | 24.8±3.6 | 25.4±4.1 | 25.7±4.2 | <.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 134±22 | 128±20 | 124±18 | <.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 77±10 | 74±9 | 71±10 | <.0001 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 75±15 | 73±14 | 70±13 | <.0001 |

| eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2(n=1365) | NA | 45±13 | 45±15 | .48 |

| LVEF, % | 38±13 | 40±12 | 43±13 | <.0001 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; NA, not available; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

The data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The proportion of patients with clinical markers of severe disease, including recent HF admissions and NYHA class III-IV symptoms, decreased. In recent periods, more patients had a long history of HF symptoms and lower blood pressure and heart rate values.

Drug and device therapiesSignificant temporal shifts were observed (table 3) in prescribed therapies in the 3 cohorts.

Changes in drug and device therapy over time

| 1999-2005 | 2006-2011 | 2012-2018 | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=547 | n=659 | n=1314 | ||

| Drug therapy | ||||

| Non-HF polypharmacya | 133 (24.3) | 200 (30.4) | 646 (49.2) | <.0001 |

| Furosemide | 474 (86.7) | 588 (89.2) | 1203 (91.6) | .001 |

| Furosemide ≥ 75 mg/d (n=1823) | 47 (27.3) | 155 (34.1) | 516 (43.1) | <.0001 |

| Digitalis | 244 (44.6) | 168 (25.5) | 161 (12.3) | <.0001 |

| Nitrates | 263 (48.1) | 223 (33.8) | 198 (15.1) | <.0001 |

| Ivabradine | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | 79 (6.0) | <.0001 |

| Oral anticoagulants | 112 (20.5) | 228 (34.6) | 708 (53.9) | <.0001 |

| RASI (dose for n=1390) | 471 (86.1) | 553 (83.9) | 992 (75.5) | <.0001 |

| On RASI at ≥ 50% target dose | 32 (19.1) | 62 (16.9) | 103 (12.0) | .004 |

| BB (dose available n=1442) | 211 (38.6) | 435 (66.0) | 1079 (82.1) | <.0001 |

| On BB at ≥ 50% target dose | 3 (2.9) | 16 (4.8) | 82 (8.2) | .007 |

| MRA | 257 (47.0) | 277 (42.0) | 720 (54.8) | <.0001 |

| RASI + BB | 99 (18.1) | 216 (32.8) | 372 (28.3) | .0004 |

| RASI + BB + MRA | 82 (15.0) | 152 (23.1) | 455 (34.6) | <.0001 |

| Drug therapy Class I indication | ||||

| OAC, AF history (n=1118) | 64 (45.1) | 166 (58.9) | 609 (87.8) | <.0001 |

| RASI HFrEF (n=1226) | 273 (86.9) | 288 (86.2) | 453 (78.4) | .0004 |

| RASI, LVEF ≥ 40%b (n=1092) | 147 (89.6) | 228 (82.9) | 490 (75.0) | <.0001 |

| BB, HFrEF (n=1226) | 144 (45.9) | 248 (74.3) | 504 (87.2) | <.0001 |

| MRA, LVEF <35% (n=801) | 114 (51.4) | 101 (47.4) | 235 (64.2) | .0007 |

| RASI + BB, HFrEF (n=1226) | 62 (19.8) | 117 (35.0) | 156 (27.0) | .0896 |

| RASI + BB + MRA, HFrEF (n=1226) | 65 (20.7) | 99 (29.6) | 245 (42.4) | <.0001 |

| Devices | ||||

| CRT-P | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 30 (2.3) | .0004 |

| CRT-D | 0 0 (0.0) | 18 (2.7) | 97 (7.4) | <.0001 |

| ICD | 16 (2.9) | 40 (6.1) | 184 (14.0) | <.0001 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BB, beta-blockers; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy- pacing; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NA, not available; OAC, oral anticoagulants; RASI, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors

The data are expressed as No. (%).

Digoxin and nitrate prescription declined, while more patients were treated with furosemide and, among these, the proportion of those who received ≥ 75mg/d showed an increasing trend. Prescription of oral anticoagulants, MRA and BB significantly rose overall, while the achievement of target GDMT doses, though on the rise, remained limited.

Notably, we found an opposite trend for RASI prescriptions and the proportion on target dose, which declined significantly in the 2012 to 2018 cohort. To explore potential reasons for this divergent trend, we performed multivariable logistic regression on RASI prescription. Among covariates detailed in Methods, RASI prescription was independently associated with kidney function (eGFR <30mL/min/1.73m2, odds-ratio [OR], 0.27, 95% confidence interval [95%CI] 0.20-0.38, P <.0001), systolic blood pressure (OR per 5mmHg increase 1.08; 95%CI, 1.05-1.11; P <.0001), LVEF (OR per 5 unit increase 0.91; 95%CI, 0.87-0.94; P <.0001), and MRA (OR, 0.81; 95%CI, 0.66-1.00; P=.049).

Prescription of HF-GDMT, and specifically RASI-BB-MRA combination therapy, was consistently higher at all time points in patients with HFrEF, when scaled to the overall cohort (table 3). The percentage on non-HF polypharmacy also rose significantly across periods.

The proportion of patients who had implanted devices at the time of enrolment reflected treatment decisions that had occurred before recruitment, hence at a younger age, and possibly earlier stage of the disease, and grew markedly across periods.

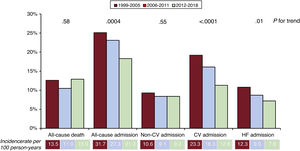

Incidence and predictors of outcomesDuring the 1-year follow-up, 308 patients died (12.2%) and 529 (21.0%) were hospitalized at least once: 216 (8.6%) for noncardiovascular causes, 360 (14.3%) for cardiovascular causes, and 210 (8.3%) for worsening HF. All-cause mortality did not change across the 3 periods (figure 2). The proportion hospitalized during 1 year, overall, for cardiovascular causes and for HF decompensations declined significantly (figure 2), while the percentage of those admitted for noncardiovascular causes was similar across cohorts.

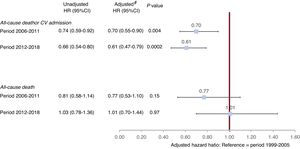

Overall, 591 patients (23.5%) met the combined primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization. On multivariable analysis, enrolment in 2006 to 2011 (hazard ratio [HR] 0.70; 95%CI, 0.55-0.90; P=.004) and 2012 to 2018 (HR, 0.61; 95%CI, 0.47-0.79; P=.0002) carried a lower risk of the primary outcome than recruitment in 1999 to 2005 after adjustment for acknowledged predictors of prognosis, considering LVEF as a continuous variable (figure 3, ). The results were similar when LVEF cutoff values for different HF phenotypes were instead included in the model (2006-2011 cohort HR, 0.69; 95%CI, 0.54-0.88; P=.003 and 2012-2018 cohort (HR, 0.60; 95%CI, 0.47-0.78; P <.0001).

Association of enrolment period with outcome. Unadjusted and adjusted Cox models. * Adjusted by age, sex, heart failure (HF) etiology, duration of HF history, HF admission in the previous year, history of atrial fibrillation, pre-existing hypertension, diabetes, previous stroke/transient ischemic attack, NYHA class III-IV, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, heart rate bpm, LVEF%, furosemide, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, implanted cardioverter defibrillator/cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator, and non-HF directed polypharmacy; covariates were selected based on clinical relevance and previous literature findings.

HF-GDMT included in the same model as a composite variable was associated with a lower risk of mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization (HR, 0.76; 95%CI, 0.63-0.91; P=.002).

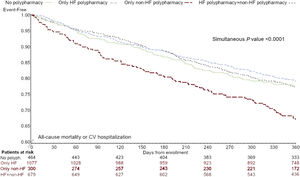

Figure 4 depicts direct adjusted survival curves for the primary endpoint in the 4 groups of polypharmacy intake: patients on non-HF polypharmacy alone had the worst prognosis (HR, 1.57 vs no polypharmacy, 95%CI, 1.18-2.09, P=.002).

Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization according to drug treatment complexity, adjusted for age, ejection fraction, systolic blood pressure, study period, heart failure etiology, NYHA class, heart failure hospitalization in the last year, history of hypertension (covariates significant by backward selection in multivariable Cox regression). HF, heart failure.

Our nationwide registry data address an evidence gap by providing novel evidence about the evolving characteristics and outcomes over the last 2 decades of octogenarians, a burgeoning population segment in Western countries that carries the largest mortality and morbidity burden from HF (figure 5).

Our octogenarian cohort shares the peculiar clinical profile previously described in the elderly, although, in agreement with enrolment and follow-up in the specialist cardiology setting, female prevalence (40%) was lower than in the general elderly population with HF.5–9

Our novel findings confirm in the oldest old the reported increase in HFpEF10,11 as a companion effect of population aging, increasing prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors,16 and declining HFrEF incidence rates with improved management of myocardial infarction. Declining blood pressure and heart rate values, a likely expression of long-standing disease and more stringent implementation of drug therapy, suggest that octogenarians may have been more aggressively treated in recent periods, by greater BB and RASI uptake and boosted decongestion strategies.

Treatment changesPatients older than 80 years have been underrepresented in clinical trials, leading to uncertainty about the efficacy of cornerstone therapies for HFrEF in this population.24 Overzealous guideline implementation may not improve outcomes for very elderly patients, in whom competing comorbidity may more strongly affect prognosis.25 Careful follow-up and therapeutic tailoring deriving from implementation of organizational changes at our multidisciplinary HF outpatient clinics, through nationwide networking and nurse-led education, deserve much of the credit, besides therapeutic interventions, for progress in care in such a delicate population.

In our octogenarians, 2 cornerstones HF therapies, MRA and BB, and anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation were consistently implemented over time.

Treatment rates were superior both to those in the United Kingdom general HF population3 and in the United States PINNACLE registry,26 and aligned with the European Observational Research Program Heart Failure Long-Term Registry 2011 to 2016 data among participants with a median age of 66 years,14 except for RASI. The CHECK investigators8 also reported, among octogenarians with HFrEF seen at Dutch HF outpatient clinics in 2013 to 2016, higher prescription rates for BB than RASI. Aggressive decongestion, as suggested by more common high-dose27 furosemide prescription in 2012 to 2018, and its attendant adverse effects of hypotension in the setting of impaired renal function, provide a putative justification for the decrease over time in RASI prescription and dosing: in our series, the odds of lower RASI prescription were associated with variables reflecting a mix of possible intolerance, drug interference, and uncertain indication.28 When considering that 1 in 5 of our octogenarians did not receive RASI or BB, the evolving evidence of benefit and low adverse event rates from SGLT2 inhibitors in HF patients, irrespective of LVEF level,29,30 paves the way22 for novel drug prioritization strategies to improve the management of elderly HF patients.

Evolving prognosisVery poor outcomes have consistently been reported in the elderly with HF15 with no changes in mortality in multiple community-based cohort samples from 1990 to 2013.15,26,31 One-year mortality in our most recent cohort (2012-2018) was 12.9%, a relatively small excess mortality compared with the 11.6% rate from our 2017 National Census32 among participants aged 80 to 94 years. In the general population of this age group, HF may represent one of many comorbidities and geriatric syndromes influencing survival, while frail home-bound patients, those with logistic and transportation problems or other more severe and prioritized comorbidities, are less likely to attend outpatient clinics and receive specialist management.

Our registry data show a significant decline across 2 decades in the proportion of octogenarians with HF who were readmitted during the first year after enrolment. In agreement with previous findings in cardiology trial settings,33 noncardiovascular causes accounted for over one third of readmissions, a proportion that did not change over time. The decrease in hospitalizations, which paralleled the uptake of oral anticoagulants, BB and MRA and, to a lesser extent, cardiac resynchronization therapy, was entirely linked to readmissions for cardiovascular causes and in particular for HF decompensation. Moreover, since the risk of stroke and HF hospitalization are similar in patients with atrial fibrillation and both HFrEF and HFpEF,34 the implementation of anticoagulation might have substantially contributed to the declining proportion of cardiovascular hospitalizations across phenotypes in our series. Declining morbidity represents a pivotal achievement in a patient group that may be focused on the quality rather than the quantity of remaining life, particularly when severely symptomatic.35

The favorable trends in outcomes observed over the last 2 decades in our series will likely be deeply altered by the disproportionate pandemic impact on elderly HF patients.36,37 Moreover, although telehealth intervention may be feasible during periods of restricted in-person access to outpatient facilities, without increases in subsequent hospital encounters or mortality,38 oldest old patients, who face sensory and cognitive barriers to the use of technology, are likely to require specific provisions to access remote care.

Disentangling the impact of polypharmacyFrailty and polypharmacy are both highly prevalent and linked to adverse outcomes in the elderly.39,40 To account for the dual significance of polypharmacy, ie, a marker of greater GDMT prescription on the one hand and of clinical complexity on the other, in our HF outpatient clinic setting, we separately analyzed the 2 treatment components. The 2-fold increase in the proportion of participants on non-HF polypharmacy points to the expanding multimorbidity and clinical complexity of recruited patients across 2 decades. Patients with non-HF polypharmacy who did not receive HF-GDMT had the worst prognosis even after multivariate adjustment, suggesting that in our cohort this label may encompass unmeasured confounders linked to frailty. On the other hand, since polypharmacy may result in decreased therapeutic adherence and a higher risk of drug-related adverse events, accurate and complete medication reconciliation, and deprescribing of redundant medications, should represent a primary target during outpatient follow-up, to prevent avoidable hospitalizations in this age stratum.

LimitationsOur data derive from a long-term observational registry, which does not allow inferences on causation. Our findings cannot be extended to the general octogenarian population, since being on specialist follow-up might per se represent a selection bias. Changes in diagnostic methods over time might have impacted on LVEF values, together with a greater awareness of HFpEF as a clinical entity in cardiology practice and changes in hospital discharge coding accuracy. Laboratory data were consistently collected only in the 2 most recent cohorts. Natriuretic peptides, which seem to maintain their value as a marker of severity and outcomes in the elderly, were not available. We did not collect information on socioeconomic deprivation, quality of life, or cognitive, sensory, or motor impairment, which represent important dimensions with prognostic value in the assessment of geriatric populations.41

CONCLUSIONSOver a 20-year period, the characteristics and outcomes of octogenarians enrolled in a nationwide HF registry have substantially changed, reflecting demographic variations, the evolution of cardiovascular risk factors, and improved implementation of BB, MRA, and electrical device therapy. The survival of octogenarians remained stable over time and on average close to that of the general population of the same age group, while the proportion admitted to hospital for cardiovascular causes declined. These data suggest that, despite increasing patient complexity, in the cardiology setting the burden of HF in the elderly is declining.

FUNDINGSince the start of IN-HF online (formerly IN-CHF registry), the following companies have partially supported the registry: Merck Sharpe & Dohme (1995-2015); Novartis (2004-2010); Abbott, Medtronic (2007-2010); Abbott, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Servier, and Vifor (2017-2019).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSR. De Maria and L. Gonzini had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: R. De Maria, M. Iacoviello, M. Gori, and M. Marini. Acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data: M. Benvenuto, L. Cassaniti, A. Municinò, A. Navazio, E. Ammirati, G. Leonardi, N. Pagnoni, L. Montagna, M. Catalano, P. Midi, A.M. Floresta, and G. Pulignano. Drafting of the manuscript: R. De Maria, Mauro Gori, and L. Gonzini. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M. Benvenuto, L. Cassaniti, A. Municinò, A. Navazio, E. Ammirati, G. Leonardi, N. Pagnoni, L. Montagna, M. Catalano, P. Midi, A.M Floresta, and G. Pulignano. Statistical analysis: L. Gonzini. Supervision: M. Iacoviello.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTM. Benvenuto, L. Cassaniti, M. Catalano, R. De Maria, A.M. Floresta, L. Gonzini, M. Gori, M. Iacoviello, G. Leonardi, M. Marini, L. Montagna, A. Municinò, P. Midi, A. Navazio, N. Pagnoni, G. Pulignano have no conflicts of interest to disclose. E. Ammirati reports personal fees from KINIKSA PHARMACEUTICAL, during the conduct of the study.

Heart failure (HF) affects more than 10% of people older than 80 years, the fastest growing population segment in Europe. Data are scarce on the trend in risk factor prevalence, drug treatment and outcomes among octogenarians with chronic HF.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?Over 2 decades, the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the preserved HF phenotype increased, while recommended therapies were steadily implemented. Although age at enrolment and polypharmacy rose, 1-year survival was stable, while the proportion of patients hospitalized for cardiovascular causes decreased. Octogenarians are increasingly managed in cardiology settings, with declining morbidity, despite increasing clinical complexity.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to professors Luigi Tavazzi and Aldo P. Maggioni, for planting the seed and tending the Italian Network on Heart Failure with unrelenting commitment for a quarter of century.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2022.03.002