Ischemic heart disease continues to cause high morbidity and mortality. Its prevalence is expected to increase due to population aging, and its prevention is a major goal of health policies. The risk of developing ischemic heart disease is related to a complex interplay between genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. In the last decade, considerable progress has been made in knowledge of the genetic architecture of this disease. This narrative review provides an overview of current knowledge of the genetics of ischemic heart disease and of its translation to clinical practice: identification of new therapeutic targets, assessment of the causal relationship between biomarkers and disease, improved risk prediction, and identification of responders and nonresponders to specific drugs (pharmacogenomics).

Keywords

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, with a 2015 report assigning 14.1% of disability-adjusted life years to cardiovascular disease in general and 6.7% to ischemic heart disease (IHD) in particular.1 Ischemic heart disease is a complex multifactorial disease influenced by environmental factors that include lifestyle (diet, physical activity, and smoking), genetic factors, and interactions between these.2

In the last 10 years, major advances have been made in our knowledge of the genetic architecture of IHD as well as the translation of the acquired knowledge to clinical practice.3 This narrative review summarizes current knowledge about the genetic basis of IHD, presents examples of the impact of this knowledge on clinical practice, and outlines future challenges.

ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASEThe genetic architecture of a phenotypic trait (a quantifiable biological feature) refers to the genes and their variants that determine or are associated with the trait of interest.

Before embarking on a study of the genetic architecture of a trait it is important to first determine whether the genetic component is important. Several cohort studies have shown that a family history of IHD is associated with an elevated risk of developing the disease,4,5 suggesting that genetic factors are important; however, it is also important to consider that family background transmits not only genetic information, but also attitudes and lifestyle habits. The heritability of a trait is an indication of its percentage variation, which is related to the population genetic variation.6 Published estimates of IHD heritability range from 35% to 55%.7–9

Once the importance of the genetic component is established, studies can be designed to identify genes and genetic variants associated with IHD. In relation to genetic transmission, 2 broad groups of phenotypes or diseases can be defined:

- •

Monogenic (or oligogenic), in which the risk of developing the disease is associated with the presence of variants in a single gene or a small number of genes. A good example is familial hypercholesterolemia, whose appearance is determined by sequence variants in a discrete group of genes (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, and LDLRAP1).10,11

- •

Polygenic or complex, in which disease risk is determined by multiple genes, numerous variants of these genes, and their interaction with environmental factors.12 IHD is a clear example of a polygenic or complex trait.

The genetic architecture of a phenotypic trait can be studied through 4 approaches:

- 1.

Linkage analysis. This type of analysis has proved useful in the study of monogenic and oligogenic diseases. Linkage studies are performed in families in which the disease is initially diagnosed in at least 1 member (the proband), and other family members with the disease are also found in more than 1 generation.13,14 Family members are analyzed for several hundred genetic markers distributed throughout the genome, and the generational tranmission of these markers is analyzed to identify any association with disease appearance (segregation). The goal is to locate the genomic region housing the gene and identify the disease-causing genetic variant. Once the genomic region is identified, further studies are performed, including genotyping and usually sequencing, to identify the gene and the disease-causing variant with greater precision. This type of analysis has been very useful in studies of monogenic and oligogenic diseases. For example, in familial hypercholesterolemia, linkage analysis identified a region in chromosome 1 containing the PCSK9 gene,15 and subsequent sequencing analysis identified PCSK9 sequence variants that cause the disease.16 Although linkage analysis has been less useful in the study of complex diseases,17 IHD-associated sequence variants have been identified in the ALOX5AP and MEF2A genes.18,19

- 2.

Candidate-gene association studies. This type of analysis classically uses a case-control design to determine if one or more variants of a specific gene are more or less frequent in patients with the disease than in healthy control individuals. In this hypothesis-testing approach, the candidate gene is selected according to knowledge of the disease pathophysiology, and the analyzed genetic variants tend to be common (allele frequency > 5%). Candidate-gene association studies have contributed little to knowledge of the genetic architecture of IHD or other complex phenotypes.20 The main problem with this approach is poor reproducibility, generally linked to the small sample size in these studies, which results in insufficient statistical power to identify weakly associated variants.

- 3.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Over the past 20 years, new technologies for genome sequencing and genotying multiple sequence variants in the same sample have advanced our knowledge of the genetic basis of complex diseases. Moreover, the publication of the HapMap study21,22 revealed that many common sequence variants are associated at the population level (they are in linkage disequilibrium). Together with technological advances, knowledge of the linkage disequilibrium pattern in the human genome led to the development of laboratory kits able to detect between 100 000 and 500 000 sequence variants. This type of analysis captures a large proportion of the common genetic variation in the human genome and has permitted the design of GWAS approaches, which are used for the hypothesis-free study of hundreds of thousands of genetic features and their relationship to the phenotypic trait of interest. The lack of a guiding hypothesis has 2 major implications for GWAS design and interpretation: a) in a discovery sample, a series of sequence variants are identified that show a potential association with the trait of interest, and the results from this initial sample are validated by replication in an independent sample; b) the simultaneous analysis of hundreds of thousands of sequence variants generates a huge number of multiple comparisons, and the P value for assigning statistical significance tends to be < 1 × 10−8.

Early work with GWAS indicated that common genetic variants show only a weak association with complex traits of interest, with the odds ratio (OR) ranging from 1.1 to 1.4. The need to identify weakly associated variants with such small P values and to replicate the findings in independent samples has engendered international collaborations that have assembled samples comprising thousands of individuals.

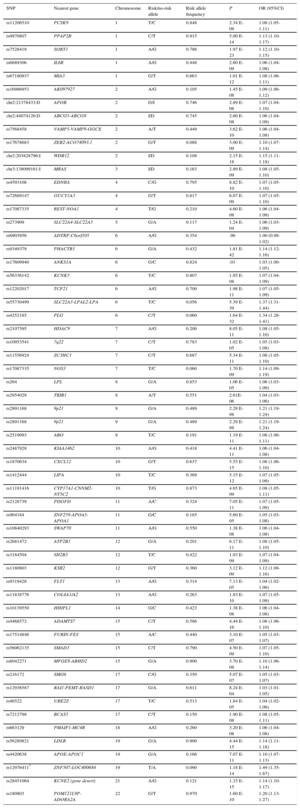

The first 2 GWAS of IHD produced consistent results, identifying sequence variants in chromosome 9 associated with increased disease risk.23,24 Several GWAS have been published since,25 and in 2015 a meta-analysis of the accumulated findings identified 55 IHD-associated loci, each with 1 or more sequence variants (Table 1).26 These variants explain approximately 15% of IHD heritibility; moreover, some of them are also related to lipid metabolism, blood pressure, and inflammation, confirming the importance of these risk factors in IHD etiology and pathogenesis.27 More recent systems biology approaches identified overrepresentation of IHD-associated genes in several processes and metabolic pathways, including lipid metabolism, sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism, polyamine metabolism, innate immunity, extracellular matrix degradation, and the collapsin response mediator protein family.28 Moreover, most of these variants are located in intergenic regions close to gene promoters, indicating a possible influence on expression and highlighting the importance of gene expression and epigenetics in determining IHD risk.29 All GWAS results related to IHD, its risk factors, and other complex traits have been catalogued to provide easy access to researchers and clinicians.25

Table 1.Summary of the Main Results of a Recent Meta-analysis of Genome-wide Association Studies Examining DNA Sequence Variants Associated With Ischemic Heart Disease*

SNP Nearest gene Chromosome Risk/no-risk allele Risk allele frequency P OR (95%CI) rs11206510 PCSK9 1 T/C 0.848 2.34 E-08 1.08 (1.05-1.11) rs9970807 PPAP2B 1 C/T 0.915 5.00 E-14 1.13 (1.10-1.17) rs7528419 SORT1 1 A/G 0.786 1.97 E-23 1.12 (1.10-1.15) rs6689306 IL6R 1 A/G 0.448 2.60 E-09 1.06 (1.04-1.08) rs67180937 MIA3 1 G/T 0.663 1.01 E-12 1.08 (1.06-1.11) rs16986953 AK097927 2 A/G 0.105 1.45 E-08 1.09 (1.06-1.12) chr2:21378433:D APOB 2 D/I 0.746 2.89 E-08 1.07 (1.04-1.10) chr2:44074126:D ABCG5-ABCG8 2 I/D 0.745 2.60 E-08 1.06 (1.04-1.09) rs7568458 VAMP5-VAMP8-GGCX 2 A/T 0.449 3.62 E-10 1.06 (1.04-1.08) rs17678683 ZEB2-ACO74093.1 2 G/T 0.088 3.00 E-09 1.10 (1.07-1.14) chr2:203828796:I WDR12 2 I/D 0.108 2.15 E-18 1.15 (1.11-1.18) chr3:138099161:I MRAS 3 I/D 0.163 2.89 E-09 1.08 (1.05-1.10) rs4593108 EDNRA 4 C/G 0.795 8.82 E-10 1.07 (1.05-1.10) rs72689147 GUCY1A3 4 G/T 0.817 6.07 E-09 1.07 (1.05-1.10) rs17087335 REST-NOA1 4 T/G 0.210 4.60 E-08 1.06 (1.04-1.09) rs273909 SLC22A4-SLC22A5 5 G/A 0.117 1.24 E-04 1.06 (1.03-1.09) rs6903956 ADTRP-C6orf105 6 A/G 0.354 .96 1.00 (0.98-1.02) rs9349379 PHACTR1 6 G/A 0.432 1.81 E-42 1.14 (1.12-1.16) rs17609940 ANKS1A 6 G/C 0.824 .03 1.03 (1.00-1.05) rs56336142 KCNK5 6 T/C 0.807 1.85 E-08 1.07 (1.04-1.09) rs12202017 TCF21 6 A/G 0.700 1.98 E-11 1.07 (1.05-1.09) rs55730499 SLC22A3-LPAL2-LPA 6 T/C 0.056 5.39 E-39 1.37 (1.31-1.44) rs4252185 PLG 6 C/T 0.060 1.64 E-32 1.34 (1.28-1.41) rs2107595 HDAC9 7 A/G 0.200 8.05 E-11 1.08 (1.05-1.10) rs10953541 7q22 7 C/T 0.783 1.02 E-05 1.05 (1.03-1.08) rs11556924 ZC3HC1 7 C/T 0.687 5.34 E-11 1.08 (1.05-1.10) rs17087335 NOS3 7 T/C 0.060 1.70 E-09 1.14 (1.09-1.19) rs264 LPL 8 G/A 0.853 1.06 E-05 1.06 (1.03-1.09) rs2954029 TRIB1 8 A/T 0.551 2.61E-06 1.04 (1.03-1.06) rs2891168 9p21 9 G/A 0.489 2.29 E-98 1.21 (1.19-1.24) rs2891168 9p21 9 G/A 0.489 2.29 E-98 1.21 (1.19-1.24) rs2519093 ABO 9 T/C 0.191 1.19 E-11 1.08 (1.06-1.11) rs2487928 KIAA1462 10 A/G 0.418 4.41 E-11 1.06 (1.04-1.08) rs1870634 CXCL12 10 G/T 0.637 5.55 E-15 1.08 (1.06-1.10) rs1412444 LIPA 10 T/C 0.369 5.15 E-12 1.07 (1.05-1.09) rs11191416 CYP17A1-CNNM2-NT5C2 10 T/G 0.873 4.65 E-09 1.08 (1.05-1.11) rs2128739 PDGFD 11 A/C 0.324 7.05 E-11 1.07 (1.05-1.09) rs964184 ZNF259-APOA5-APOA1 11 G/C 0.185 5.60 E-05 1.05 (1.03-1.08) rs10840293 SWAP70 11 A/G 0.550 1.38 E-08 1.06 (1.04-1.08) rs2681472 ATP2B1 12 G/A 0.201 6.17 E-11 1.08 (1.05-1.10) rs3184504 SH2B3 12 T/C 0.422 1.03 E-09 1.07 (1.04-1.09) rs1180803 KSR2 12 G/T 0.360 3.12 E-09 1.12 (1.08-1.16) rs9319428 FLT1 13 A/G 0.314 7.13 E-05 1.04 (1.02-1.06) rs11838776 COL4A1/A2 13 A/G 0.263 1.83 E-10 1.07 (1.05-1.09) rs10139550 HHIPL1 14 G/C 0.423 1.38 E-08 1.06 (1.04-1.08) rs4468572 ADAMTS7 15 C/T 0.586 4.44 E-16 1.08 (1.06-1.10) rs17514846 FURIN-FES 15 A/C 0.440 3.10 E-07 1.05 (1.03-1.07) rs56062135 SMAD3 15 C/T 0.790 4.50 E-09 1.07 (1.05-1.10) rs8042271 MFGE8-ABHD2 15 G/A 0.900 3.70 E-08 1.10 (1.06-1.14) rs216172 SMG6 17 C/G 0.350 5.07 E-07 1.05 (1.03-1.07) rs12936587 RAI1-PEMT-RASD1 17 G/A 0.611 8.24 E-04 1.03 (1.01-1.05) rs46522 UBE2Z 17 T/C 0.513 1.84 E-05 1.04 (1.02-1.06) rs7212798 BCAS3 17 C/T 0.150 1.90 E-08 1.08 (1.05-1.11) rs663129 PMAIP1-MC4R 18 A/G 0.260 3.20 E-08 1.06 (1.04-1.08) rs56289821 LDLR 19 G/A 0.900 4.44 E-15 1.14 (1.11-1.18) rs4420638 APOE-APOC1 19 G/A 0.166 7.07 E-11 1.10 (1.07-1.13) rs12976411* ZNF507-LOC400684 19 T/A 0.090 1.18 E-14 1.49 (1.35-1.67) rs28451064 KCNE2 (gene desert) 21 A/G 0.121 1.33 E-15 1.14 (1.10-1.17) rs180803 POM121L9P-ADORA2A 22 G/T 0.970 1.60 E-10 1.20 (1.13-1.27) A, adenine; C, cytosine; D, deletion; G, guanine; I, insertion; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; T, thymine; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

The main benefits of GWAS are the consistency of the results obtained, the creation of intergroup collaborations, and the placing of data (crude and aggregate) at the disposal of the scientific community. The available GWAS databases include the European Genome-phenome Archive,30 the American database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP),31 and the aggregate database of IHD-associated genetic variants from the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D consortium,32 which includes data from more than 60 000 patients and more than 123 000 control participants.

The major limitations of GWAS are that the identified sequence variants need not be causally related to the phenotype in question (they could be in linkage disequilibrium with the causal variant) and that they provide no information about the associated pathophysiological mechanism, which therefore has to be identified through specific functional studies. Also, because GWAS involve collaborations, the definition of the clinical phenotype being studied can vary. Moreover, these studies are fundamentally aimed at identifying common sequence variants with small effects and are less suited to identifying rare variants with larger effects.

Characterizing the as-yet undiscovered heritable component is one of the major challenges in the genetics of complex diseases.33 This heritability could be linked to as-yet undiscovered sequence variants of disease-associated genes. Alternatively, it could be related to changes elsewhere that do not affect the base sequence of the gene of interest but instead modulate its DNA structure, influencing its expression through epigenetic changes.

- 4.

Genome sequencing studies. Sequencing methodology was classically used to study monogenic and oligogenic diseases that show a clear familial segregation. Sequencing studies can be focused on a single gene, a panel of genes, the exome (the part of the genome that encodes proteins), or the entire genome. The human genome contains around 3100 million nucleotides, with the exome including just 30 million nucleotides and around 23 000 genes.34 The present review does not discuss the usefulness and limitations of sequencing methods applied to the study of monogenic and oligogenic diseases; these issues are addressed elsewhere.35,36 Massive sequencing studies of IHD can identify rare genetic variants that theoretically would have a larger effect than more common variants. In a recent study, discovery exome sequencing was followed by targeted exon sequencing in around 6700 patients and 6700 controls; the analysis identified rare LDLR and APOA5 sequence variants associated with a higher risk of acute myodardial infarction (OR from 1.5 to 4.5), giving renewed support for the important influence on cardiovascular risk of lipid metabolites (low-density lipoprotein colesterol [LDL-C] and triglycerides).37 Other studies have centered on specific genes, and have also identified rare IHD-associated variants in genes involved in lipid metabolism: APOC3,38NPC1L1,39SCARB1,40 and ANGPTL4, LPL, and SVEP1.41

Knowledge of the genetic architecture of IHD has clinical applications in the identification of new therapeutic targets, improvements to cardiovascular risk estimation, and pharmacogenomics.

Identification of New Therapeutic TargetsGenetics can be a very useful tool in the discovery and validation of therapeutic targets.42 In general, 3 broad strategies have been adopted: association studies (genotying and sequencing), Mendelian randomization studies, and large-scale sequencing of loss-of-function variants.

Association StudiesTo date, GWAS approaches have identified 55 IHD-associated gene loci.25–27 Of these, only one third are linked to classic risk factors, suggesting potential for the identification of new mechanisms and therapeutic targets. In a recent meta-analysis of 361 GWAS published before February 2001, 991 trait-associated genes were identified as potential drug targets.43 The same study found that in 63 patients, the identified gene was the target of a drug already used to treat or prevent the disease in question. Moreover, in another 92 patients, the trait-associated gene was the target of a drug or drugs used to treat another disease, suggesting the potential for drug repositioning.

Despite these encouraging findings, the identification of a disease-associated sequence variant does not confirm the gene as a therapeutic target. An example of an identified gene that has become a drug target is PCSK9. This gene was shown by linkage analysis to be associated with familial hypercholesterolemia,15,16 and subsequent research showed that the encoded enzyme PCSK9 increases LDL-C levels by triggering LDL receptor degradation.44,45 Specifically designed anti-PCSK9 antibodies have been shown to reduce LDL-C levels, and these PCSK9 inhibitors are currently under evaluation in phase III clinical trials of their efficacy in preventing clinical events.46,47

More often, the identified disease-association does not lead to a new therapy, signaling the need to define the mechanism of association between the sequence variant and the disease trait. An example is provided by the 9p21 region, which was shown to be associated with IHD in the first GWAS reports, published in 2007.23,24 The IHD-associated sequence variants are located in an intergenic region close to a gene cluster that encodes cell-cycle regulators (CDKN2A and CDKN2B) and the noncoding RNA CDKN2BAS (also called ANRIL). Several explanations have been proposed for the association with IHD, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear,48 impeding the design of new drugs for cardiovascular prevention.49

Mendelian Randomization StudiesIn this approach, genetic variants are used as tools to determine whether the association between a biomarker and a disease is causal, which is a prerequisite for the biomarker's candidacy as a therapeutic target. Mendelian randomization studies are based on 2 fundamental biological principles: a) that sequence variants segregate randomly during meiosis, and b) that the alleles of one gene are transmitted from each generation to the next independently of the alleles of other genes, in accordance with Mendel's law of independent assortment. In practical terms, these principles imply that the sequence variant in question is the only factor differentiating between carriers and noncarriers of the associated biomarker. Consequently, the study of the sequence variant can be likened to a randomized clinical trial of an intervention present since birth.

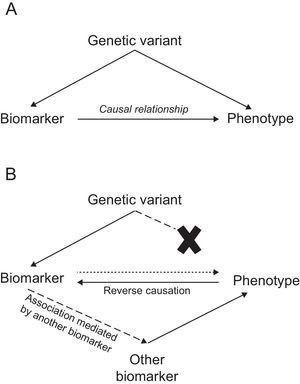

In this type of study, a disease-associated biomarker is examined together with 1 or more sequence variants associated with that biomarker to determine whether these variants are associated with the disease. The presence of such an association would suggest that the biomarker is causally related to the disease phenotype. In contrast, its absence would indicate that the relationship between biomarker and disease is noncausal, and might instead present an example of reverse causation or mediation by another biomarker (Figure).

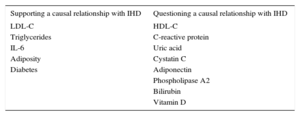

Mendelian randomization studies of IHD biomarkers support a causal relationship for LDL-C50,51, triglycerides,50–52 interleukin 6,53 adiposity,54 and diabetes55,56; in contrast, this type of analysis has questioned the causality of the association with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,50,51,57 C-reactive protein,58,59 uric acid,60 cystatin C,61 adiponectin,62 phospholipase A2,63,64 bilirubin,65 and vitamin D (Table 2).66 Mendelian randomization analysis has also shown that the PCSK9 sequence variants associated with lower LDL-C concentrations are also associated with elevated blood glucose, waist circumference, and diabetes risk, underlining the need to monitor for possible adverse effects of anti-PCSK9 therapy.67

Results of Mendelian Randomization Studies Examining the Relationship Between Selected Biomarkers and Ischemic Heart Disease

| Supporting a causal relationship with IHD | Questioning a causal relationship with IHD |

|---|---|

| LDL-C | HDL-C |

| Triglycerides | C-reactive protein |

| IL-6 | Uric acid |

| Adiposity | Cystatin C |

| Diabetes | Adiponectin |

| Phospholipase A2 | |

| Bilirubin | |

| Vitamin D |

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IHD, ischemic heart disease; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

A highly effective approach to identifying and validating therapeutic targets is the analysis of sequence variants that cause loss of function in the encoded protein, such that the mutant protein simulates the effect of a drug blocking or reducing the activity of the functional protein. Loss-of-function variants are normally rare, and their detection in specific genes therefore requires large sample sizes and high-throughput sequencing methodology. A clear example is the validation of NPC1L1 as a target for strategies to reduce IHD risk39; NPC1L1 targeting with ezetimibe was recently confirmed for secondary prevention in the IMPROVE-IT clinical trial.68 Another therapeutic target identified with this strategy is ANGPTL4, which encodes angiopoietin-like 4. A number of loss-of-function ANGPTL4 variants have been identified and found to be associated with low triglyceride levels and a reduced risk of IHD.41,69 An anti-ANGPTL4 monoclonal antibody has been developed that effectively reduces triglyceride concentrations in animal models.69 Safety and efficacy studies are now awaited in humans.

Improved Estimation of Cardiovascular RiskThe European Society of Cardiology recommends that preventative strategies be individualized according to estimated cardiovascular risk,70 calculated with an approved risk estimation system. Several risk scales have been developed and adapted for use in Spain, including the calibrated SCORE risk chart,71 REGICOR,72 FRESCO,73 and ERICE74; however, validation data are available for only 2 of them.72,73 These scales calculate an individual's 10-year risk of having a cardiovascular or coronary event according to exposure to classic risk factors. A limitation of these risk scales is their low sensitivity, with a significant proportion of events occurring in individuals classified as being at low or moderate risk.72 This limitation is driving the evaluation of new biomarkers to improve risk scale sensitivity (especially for individuals currently classified as being at moderate risk)75 according to defined recommendations.76

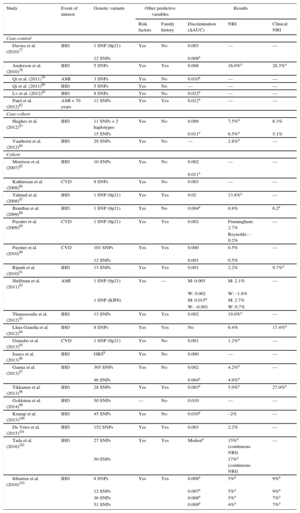

Ischemic heart disease associated genetic variants are candidate parameters for improving the predictive capacity of current risk scales. The advantages include once-in-a-lifetime determination, low cost, and the high precision of genotyping methodologies. The main disadvantage is the low association magnitude of individual sequence variants (OR from 1.1 to 1.4), which limits their predictive capacity; however, by combining several variants together in a genetic risk score, the association magnitude is increased to the level of classic risk factors. Several studies have evaluated the added value of including genetic information in classic risk scales.77–103 Almost all of these studies report an association between genetic variants and IHD risk that is independent of established cardiovascular risk factors and a family history of IHD. In most studies, the inclusion of genetic information in the risk scale did not improve discriminatory capacity; however, improvements were detected in risk classification, especially among individuals classified as at moderate risk on conventional scales (Table 3). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis found that a high genetic risk score was associated with poor prognosis among patients who already had the disease as well as with higher statin efficacy in both primary and secondary prevention.104

Main Characteristics and Results of Studies Analyzing the Added Benefit of Genetic Information in Cardiovascular Risk Estimation

| Study | Event of interest | Genetic variants | Other predictive variables | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Family history | Discrimination (ΔAUC) | NRI | Clinical NRI | |||

| Case-control | |||||||

| Davies et al. (2010)77 | IHD | 1 SNP (9p21) | Yes | No | 0.003 | — | — |

| 12 SNPs | 0.008a | ||||||

| Anderson et al. (2010)78 | IHD | 5 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.008 | 16.0%a | 28.3%a |

| Qi et al. (2011)79 | AMI | 3 SNPs | Yes | No | 0.010a | — | — |

| Qi et al. (2011)80 | IHD | 5 SNPs | Yes | No | — | — | — |

| Lv et al. (2012)81 | IHD | 8 SNPs | Yes | No | 0.022a | — | — |

| Patel et al. (2012)82 | AMI < 70 years | 11 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.012a | — | — |

| Case-cohort | |||||||

| Hughes et al. (2012)83 | IHD | 11 SNPs + 2 haplotypes | Yes | No | 0.009 | 7.5%a | 6.3% |

| 15 SNPs | 0.011a | 6.5%a | 5.1% | ||||

| Vaarhorst et al. (2012)84 | IHD | 29 SNPs | Yes | No | — | 2.8%a | — |

| Cohort | |||||||

| Morrison et al. (2007)85 | IHD | 10 SNPs | Yes | No | 0.002 | — | — |

| 0.011a | |||||||

| Kathiresan et al. (2008)86 | CVD | 9 SNPs | Yes | No | 0.003 | — | — |

| Talmud et al. (2008)87 | IHD | 1 SNP (9p21) | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | 13.8%a | — |

| Brautbar et al. (2009)88 | IHD | 1 SNP (9p21) | Yes | No | 0.004a | 0.8% | 6.2a |

| Paynter et al. (2009)89 | CVD | 1 SNP (9p21) | Yes | Yes | 0.002 | Framingham: 2.7% | — |

| Reynolds: –0.2% | |||||||

| Paynter et al. (2010)90 | CVD | 101 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.000 | 0.5% | — |

| 12 SNPs | 0.001 | 0.5% | |||||

| Ripatti et al. (2010)91 | IHD | 13 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.001 | 2.2% | 9.7%a |

| Shiffman et al. (2011)92 | AMI | 1 SNP (9p21) | Yes | — | M: 0.005 | M: 2.1% | — |

| W: 0.002 | W: –1.8% | ||||||

| 1 SNP (KIF6) | M: 0.015a | M: 2.7% | |||||

| W: –0.001 | W: 0.7% | ||||||

| Thanassoulis et al. (2012)93 | IHD | 13 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.002 | 19.0%a | — |

| Lluis-Ganella et al. (2012)94 | IHD | 8 SNPs | Yes | Yes | No | 6.4% | 17.4%a |

| Gransbo et al. (2013)95 | CVD | 1 SNP (9p21) | Yes | No | 0.001 | 1.2%a | — |

| Isaacs et al. (2013)96 | IHD | GRSb | Yes | No | 0.000 | — | — |

| Ganna et al. (2013)97 | IHD | 395 SNPs | Yes | No | 0.002 | 4.2%a | — |

| 46 SNPs | 0.004a | 4.9%a | |||||

| Tikkanen et al. (2013)98 | IHD | 28 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.003a | 5.0%a | 27.0%a |

| Goldstein et al. (2014)99 | IHD | 50 SNPs | — | No | 0.010 | — | — |

| Krarup et al. (2015)100 | IHD | 45 SNPs | Yes | No | 0.010a | –2% | — |

| De Vries et al. (2015)101 | IHD | 152 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.003 | 2.2% | — |

| Tada et al. (2016)102 | IHD | 27 SNPs | Yes | Yes | Modesta | 15%a (continuous NRI) | — |

| 50 SNPs | 17%a (continuous NRI) | ||||||

| Iribarren et al. (2016)103 | IHD | 8 SNPs | Yes | Yes | 0.008a | 5%a | 9%a |

| 12 SNPs | 0.007a | 5%a | 9%a | ||||

| 36 SNPs | 0.008a | 5%a | 7%a | ||||

| 51 SNPs | 0.009a | 4%a | 7%a | ||||

ΔAUC, change in the area under the curve (C statistic); AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GRS, genetic risk score; IHD, ischemic heart disease; M, men; NRI, net reclassification index; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; W, women.

Genetic variation can also underlie interindividual variation in drug responsiveness.105,106 In relation to cardiovascular disease, 2 prominent examples are statins and clopidogrel. Around 5% of the interindividual variation in statin-induced LDL-C reduction can be explained by genetic variation in SORT1/CELSR2/PSRC1, SLCO1B1, APOE, and LPA107; moreover, SLCO1B1 sequence variants show a consistent association with increased risk of simvastatin-induced myopathy.108

Clopidogrel is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system in the liver, releasing an active metabolite that exerts an anticoagulant effect by binding to the P2Y12 platelet receptor. One of the CYPs involved in clopidogrel metabolism is CYP2C19, and several CYP2C19 sequence variants have been identified, some increasing and others decreasing the enzyme activity. These variants might be linked to clinical events such as stent thrombosis, bleeding risk, and cardiovascular mortality. In 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the clopidogrel patient information leaflet, advising that, depending on their genetic characteristics, some patients might not experience the expected benefit with the drug.109 A consensus article published by North American scientific societies concluded that the ability of genetic tests to predict clopidogrel metabolism has not been established110; nonetheless, other societies recommend their use.111 A recent meta-analysis also concluded that current evidence does not support CYP2C19 genotype-guided individualization of clopidogrel therapy.112

FUTURE CHALLENGESKnowledge of the genetic basis of IHD has advanced significantly in recent years, contributing to a better understanding of the etiological and pathogenic mechanisms underlying the appearance and progression of this disease. These advances have, moreover, led to the identification of new therapeutic targets and improvements in cardiovascular riks estimation.113 Nonetheless, many challenges still lie ahead:

- •

Only a small proportion of disease heritability has been explained. Much further work is needed to determine how individual susceptibility to IHD is influenced by rare genetic variants with modest effects, epigenetic modifications (methylation, histones, and noncoding RNAs), and the interactions of a genetic variant with environmental factors and other genes.

- •

A major challenge in the coming years will be to integrate information originating in -omics analyses (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) and correlate it with phenotypic traits (detected with imaging modalities, functional assays, and clinical tests). It is the interaction between these information levels that determines cell function in organs and systems. Moreover, this interaction can differ between cell lines, organs, and systems, presenting a major research challenge. Continuing advances in this area will depend on the development of new analytical techniques based on large databases and systems biology approaches.

- •

The acumulated information is set to result in a more precise definition of disease traits, and in the future clinicians will likely talk less of IHD than of subgroups of conditions within this disease. This new molecular definition of disease phenotype will contribute to the development of precision medicine.

This study was supported by funds from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III-FEDER (FIS PI15/00051; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares) and the Catalan regional government through the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca. S. Sayols-Baixeras is supported by an iPFIS fellowship from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III-FEDER (IFI14/00007).

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTR. Elosua sits on the advisory committee of Gendiag and is a named inventor on a patent for Gendiag.exe, a genetic test for estimating cardiovascular risk.