To analyze hospitalization and mortality rates due to acute cardiovascular disease (ACVD).

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study of the hospital discharge database of Castile and León from 2001 to 2015, selecting patients with a principal discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), unstable angina, heart failure, or acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Trends in the rates of hospitalization/100 000 inhabitants/y and hospital mortality/1000 hospitalizations/y, overall and by sex, were studied by joinpoint regression analysis.

ResultsA total of 239 586 ACVD cases (AMI 55 004; unstable angina 15 406; heart failure 111 647; AIS 57 529) were studied. The following statistically significant trends were observed: hospitalization: ACVD, upward from 2001 to 2007 (5.14; 95%CI, 3.5-6.8; P < .005), downward from 2011 to 2015 (3.7; 95%CI, 1.0-6.4; P < .05); unstable angina, downward from 2001 to 2010 (–12.73; 95%CI, –14.8 to –10.6; P < .05); AMI, upward from 2001 to 2003 (15.6; 95%CI, 3.8-28.9; P < .05), downward from 2003 to 2015 (–1.20; 95%CI, –1.8 to –0.6; P < .05); heart failure, upward from 2001 to 2007 (10.70; 95%CI, 8.7-12.8; P < .05), upward from 2007 to 2015 (1.10; 95%CI, 0.1-2.1; P < .05); AIS, upward from 2001 to 2007 (4.44; 95%CI, 2.9-6.0; P < .05). Mortality rates: downward from 2001 to 2015 in ACVD (–1.16; 95%CI, –2.1 to –0.2; P < .05), AMI (–3.37, 95%CI, –4.4 to –2, 3, P < .05), heart failure (–1.25; 95%CI, –2.3 to –0.1; P < .05) and AIS (–1.78; 95%CI, –2.9 to –0.6; P < .05); unstable angina, upward from 2001 to 2007 (24.73; 95%CI, 14.2-36.2; P < .05).

ConclusionsThe ACVD analyzed showed a rising trend in hospitalization rates from 2001 to 2015, which was especially marked for heart failure, and a decreasing trend in hospital mortality rates, which were similar in men and women. These data point to a stabilization and a decline in hospital mortality, attributable to established prevention measures.

Keywords

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death worldwise.1–10 Ischemic heart disease, manifesting as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or unstable angina, is the leading cardiovascular disease11 and is followed in importance and as a cause of disability by acute ischemic stroke (AIS).12–14 Heart failure (HF) is frequently associated with ischemic heart disease and is a serious health problem and the leading cause of hospitalization in elderly patients.15,16 Recently, primary and secondary prevention measures have been developed to improve population cardiovascular health.17–19 These initiatives include the reduction and control of diseases such as hypertension and diabetes, statin use, a reduction in the smoking rate, improved treatment of AMI and HF, and advances in the prevention and care of AIS.20

The study of trends in cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality plays a central role in epidemiology and public health. However, the real impact of these diseases in Spain remains unclear because of the scarcity of studies on their hospitalization and hospital mortality rates.20–26 The results of such studies could help to evaluate the effectiveness of cardiovascular health campaigns and provide an assessment model for further initiatives.

However, in the absence of specific records, administrative databases, such as hospital discharge databases, have proved useful in obtaining epidemiological information from different disease measures.27,28

The objective of this study was to determine changes in trends in hospitalization and hospital mortality rates due to AMI, unstable angina, HF, and AIS in order to assess the health impact of preventive and therapeutic interventions for cardiovascular disease.

METHODSWe conducted a cross-sectional study of the hospital discharge Minimum Basic Dataset (MBDS) of Castile and León from 2001 to 2015. Patients with a principal discharge diagnosis of AMI, unstable angina, HF, or AIS were selected according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM).

Variables AnalyzedMain diagnoses according to ICD-9-CM at discharge. Codes used20:

- •

AMI: 410.xx, except 410.x2.

- •

Unstable angina: 411.xx.

- •

HF: 402.01; 402.11; 402.91; 404.01; 404.11; 404.91; 404.3; 404.13; 404.93; 428; 428.xx.

- •

AIS: 433.xx; 434.xx; 436.

Calculated hospitalization rate by population using the population census data of Castile and León, 2001 to 2015.29

Statistical AnalysisThe following rates were calculated for acute cardiovascular disease (ACVD) in general and for each disease studied:

- •

Hospitalization rate/100 000 inhabitants/y and trends over the 15 year period studied, overall and by sex.

- •

Hospital mortality rate/1000 hospitalizations and trends over the 15 year period studied, overall and by sex.

Trends over time were analyzed using linear joinpoint regression analysis to determine if these rates had undergone statistically significant changes over the period studied. This test assesses trends over time in years for the selected patient series. In this analysis, the change points (joinpoints or inflection points) show statistically significant changes in the trend (ascending or descending). Graphic joinpoint models performed on the logarithm of the rate describe a sequence of connected segments. The point at which these segments join is a joinpoint and represents a statistically significant change in the trend. In addition, for each segment, an annual percentage change was calculated for each trend using generalized linear models, assuming a Poisson distribution and showing in each case its associated statistical significance level with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), hospitalization and mortality rates stratified by sex with their respective 95%CIs, and statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using open access software provided by the Surveillance Research Program of the Unites States National Cancer Institute30–32 (). A P-value < .05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance.

RESULTSThe Castile and León hospital network is made up of 14 centers comprising 3 regional, 6 provincial, and 5 referral centers, which are structured according to their health area and the availability of different medical specialties.

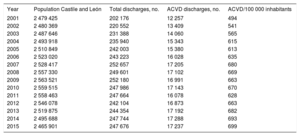

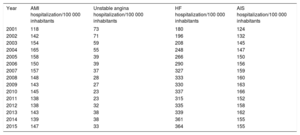

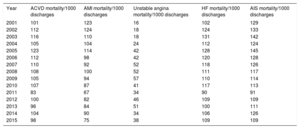

The hospital discharge MBDS of Castile and León included 3 359 572 records between 2001 and 2015. The diseases studied were selected according to the aforementioned codes and 239 586 ACVD discharge records were extracted. The mean age of the patients was 76.4 ± 12.2 years. The annual distribution of the population and discharges on which the hospitalization rate was calculated are shown in Table 1. The overall characteristics of the ACVD cases and those of each of the diseases studied are shown in Table 2. The hospitalization rates and mortality rates are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Annual Population Distribution, Number of Total Hospital Discharges and ACVD Discharges, and ACVD Hospital Discharges per 100 000 Inhabitants per Year

| Year | Population Castile and León | Total discharges, no. | ACVD discharges, no. | ACVD/100 000 inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2 479 425 | 202 176 | 12 257 | 494 |

| 2002 | 2 480 369 | 220 552 | 13 409 | 541 |

| 2003 | 2 487 646 | 231 388 | 14 060 | 565 |

| 2004 | 2 493 918 | 235 940 | 15 343 | 615 |

| 2005 | 2 510 849 | 242 003 | 15 380 | 613 |

| 2006 | 2 523 020 | 243 223 | 16 028 | 635 |

| 2007 | 2 528 417 | 252 657 | 17 205 | 680 |

| 2008 | 2 557 330 | 249 601 | 17 102 | 669 |

| 2009 | 2 563 521 | 252 180 | 16 991 | 663 |

| 2010 | 2 559 515 | 247 986 | 17 143 | 670 |

| 2011 | 2 558 463 | 247 664 | 16 078 | 628 |

| 2012 | 2 546 078 | 242 104 | 16 873 | 663 |

| 2013 | 2 519 875 | 244 354 | 17 192 | 682 |

| 2014 | 2 495 688 | 247 744 | 17 288 | 693 |

| 2015 | 2 465 901 | 247 676 | 17 237 | 699 |

ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease.

Characteristics of the Cases Analyzed, by ACVD and Each of the Diseases Studied

| ACVD | AMI | Unstable angina | HF | AIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, no. | 239 586 | 55 004 | 15 406 | 111 647 | 57 529 |

| Age, y* | 76.4 ± 12.2 | 69.90 ± 13.5 | 71.7 ± 12.5 | 80.4 ± 9.8 | 76.0 ± 11.7 |

| Age (%) | |||||

| < 65 y | 16 | 33 | 26 | 7 | 15 |

| ≥ 65 y | 84 | 67 | 74 | 93 | 85 |

| Sex, % | |||||

| Men | 56 | 72 | 66 | 46 | 55 |

| Women | 44 | 28 | 34 | 54 | 45 |

| Hospital mortality 2001-2015, % | 10.5 | 9.6 | 3.4 | 11.2 | 12.1 |

ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HF, heart failure.

Hospitalization Rates for the Different Diseases Studied per 100 000 Inhabitants per Year

| Year | AMI hospitalization/100 000 inhabitants | Unstable angina hospitalization/100 000 inhabitants | HF hospitalization/100 000 inhabitants | AIS hospitalization/100 000 inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 118 | 73 | 180 | 124 |

| 2002 | 142 | 71 | 196 | 132 |

| 2003 | 154 | 59 | 208 | 145 |

| 2004 | 165 | 55 | 248 | 147 |

| 2005 | 158 | 39 | 266 | 150 |

| 2006 | 150 | 39 | 290 | 156 |

| 2007 | 157 | 37 | 327 | 159 |

| 2008 | 148 | 28 | 333 | 160 |

| 2009 | 143 | 27 | 330 | 163 |

| 2010 | 145 | 23 | 337 | 166 |

| 2011 | 138 | 23 | 315 | 152 |

| 2012 | 138 | 32 | 335 | 158 |

| 2013 | 143 | 38 | 339 | 162 |

| 2014 | 139 | 38 | 361 | 155 |

| 2015 | 147 | 33 | 364 | 155 |

AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HF, heart failure.

Mortality Rates for the Different Diseases Studied per 1000 Hospital Discharges and Year

| Year | ACVD mortality/1000 discharges | AMI mortality/1000 discharges | Unstable angina mortality/1000 discharges | HF mortality/1000 discharges | AIS mortality/1000 discharges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 101 | 123 | 16 | 102 | 129 |

| 2002 | 112 | 124 | 18 | 124 | 133 |

| 2003 | 116 | 110 | 18 | 131 | 142 |

| 2004 | 105 | 104 | 24 | 112 | 124 |

| 2005 | 123 | 114 | 42 | 128 | 145 |

| 2006 | 112 | 98 | 42 | 120 | 128 |

| 2007 | 110 | 92 | 52 | 118 | 126 |

| 2008 | 108 | 100 | 52 | 111 | 117 |

| 2009 | 105 | 94 | 57 | 110 | 114 |

| 2010 | 107 | 87 | 41 | 117 | 113 |

| 2011 | 83 | 67 | 34 | 90 | 91 |

| 2012 | 100 | 82 | 46 | 109 | 109 |

| 2013 | 96 | 84 | 51 | 100 | 111 |

| 2014 | 104 | 90 | 34 | 106 | 126 |

| 2015 | 98 | 75 | 38 | 109 | 109 |

ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HF, heart failure.

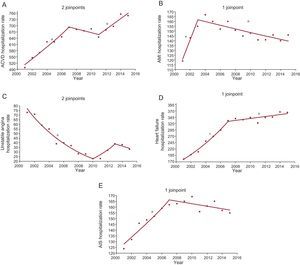

The following inflection points and statistically significant trends were observed: ACVD, changes in 2007 and 2011, upward trend from 2001 to 2007, downward from 2007 to 2011, and downward from 2011 to 2015; unstable angina, changes in 2010 and 2013, downward trend from 2001 to 2010, upward from 2010 to 2013, and downward from 2013 to 2015; AMI, change in 2003, upward trend from 2001 to 2003, and downward from 2003 to 2015; HF, change in 2007, upward trend from 2001 to 2007, and upward from 2007 to 2015; AIS, change in 2007, upward trend from 2001 to 2007, and downward from 2007 to 2015 (Figure 1).

Hospitalization rates per 100 000 inhabitants. Analysis by groups of diseases studied. Joinpoints and APC. A: ACVD; joinpoints, 2007 and 2011; APC 2001-2007, 5.14 (95%CI, 3.5-6.8, P <.05*); 2007-2011, –1.3 (95%CI, –5.4 to 2.8, P = 0.4); 2011-2015, 3.70 (95%CI, 1.0-6.4, P <.05*). B: AMI; joinpoint, 2003; APC 2001-2003, 15.66 (95%CI, 3.8-28.9, P <.05*); 2003-2015, –1.20 (95%CI, –1.8 to –0.6, P <.05*). C: unstable angina; joinpoints, 2010 and 2013; APC 2001-2010, –12.73 (95%CI, –14.8 to –10.6, P <.05*); 2010-2013, 19.43 (95%CI, –15.6 to 69, P = 0.2); 2013-2015, –6.04 (95%CI, –30.5 to 27.1, P = 0.6). D: heart failure; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 10.70 (95%CI, 8.7-12.8, P <.05*); 2007-2015, 1.10 (95%CI, 0.1-2.1, P <.05*). E: AIS, joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 4.44 (95%CI, 2.9-6.0, P <.05*); 2007-2015, –0.68 (95%CI, –0.7 to –1.7, P = 0.1). ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APC, annual percentage change; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval;

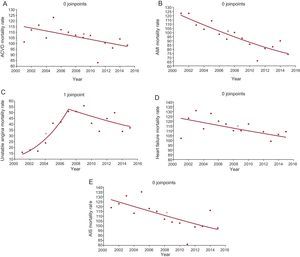

, Exact annual value. * Statistically significant APC.The following inflexion points and statistically significant trends were observed: ACVD, downward trend from 2001 to 2015 without inflection points; unstable angina, change in 2007, upward trend from 2001 to 2007, and downward from 2007 to 2015; AMI, downward trend from 2001 to 2015 without inflection points; HF, downward trend from 2001 to 2015 with no inflection points; AIS, downward trend from 2001 to 2015 without inflection points (Figure 2).

Hospital mortality rates per 1000 admissions. Analysis by groups of diseases studied. Joinpoints and APC. A: ACVD; APC 2001-2015, -1.16 (95%CI, –2.1 to –0.2, P <.05*). B: AMI; APC 2001-2015, –3.37 (95%CI, –4.4 to –2.3, P <.05*). C: unstable angina; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 24.73 (95%CI, 14.2-36.2, P <.05*); 2007-2015, –4.05 (95%CI, –9.3 to 1.5, P = 0.1). D: heart failure; APC 2001-2015, –1.25 (95%CI, –2.3 to –0.1, P <.05*). E: AIS; APC 2001-2015, –1.78 (95%CI, –2.9 to –0.6, P <.05*). ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APC, annual percentage change; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval;

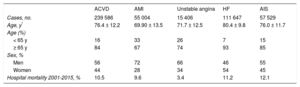

, exact annual value. * Statistically significant APC.The hospitalization and mortality rates of the diseases analyzed stratified by sex are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. The only difference between these rates was observed in unstable angina. Its hospitalization rate decreased in women and increased in men until 2004 and 2010, respectively, while its mortality rate increased in women and men until 2006 and 2007, respectively, thereafter becoming stable without significant changes.

Hospitalization rates per 100 000 inhabitants stratified by sex. Analysis by groups of diseases studied. Joinpoints and APC. A: ACVD, men; joinpoint, 2004; APC 2001-2004, 6.8 (95%CI, 1.4-12.5, P <.05*); 2004-2015, 0.7 (95%CI, 0.1-1.4, P <.05*). B: ACVD, women; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 6.2 (95%CI, 4.6-7.8, P <.05*); 2007-2015, 0.1 (95%CI, –0.7 to 1.0, P = 0.8). C: AMI, men; joinpoint, 2003; APC 2001-2003, 13.8 (95%CI, 4.0-24.5, P <.05*); 2003-2015, -0.9 (95%CI, –1.4 to –0.4, P <.05*). D: AMI, women; joinpoints, 2004 and 2010; APC 2001-2004, 14.0 (95%CI, 4.5-24.5, P <.05*); 2004-2010, –4.3 (95%CI, –7.7 to –0.7, P <.05*); 2010-2015, 1.0 (95%CI, –2.8 to 4.8, P = 0.6). E: unstable angina, men; joinpoint, 2010; APC 2001-2010, –12.9 (95%CI, –15.8 to –9.9, P <.05*); 2010-2015, 12.4 (95%CI, 1.5-24.4, P <.05*). F: unstable angina, women; joinpoint, 2004. APC 2001-2004, 10.0 (95%CI 5.3-15.0, P <.05*); 2004-2015, 0.7 (95%CI, –0.1 to 1.5, P = 0.1). G: heart failure, men; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 10.2 (95%CI, 7.6-12.9, P <.05*); 2007-2015, 1.5 (95%CI, 0.3-2.8, P <.05*). H: heart failure, women; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 10.2 (95%CI, 9.2-13.1, P <.05*); 2007-2015, 0.7 (95%CI, –0.2 to 1.6, P = 0.1). I: AIS, men; joinpoint, 2006; APC 2001-2006, 5.5 (95%CI, 2.7-8.4, P <.05*); 2006-2015, –0.5 (95%CI, –1.6 to 0.5, P = 0.3). J: AIS, women; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 4.1 (95%CI, 2.5-5.6, P <.05*); 2007-2015, –0.3 (95%CI, –1.2 to 0.6, P <.05*). ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APC, annual percentage change; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval;

, exact annual value. * Statistically significant APC.Hospital mortality rates per 1000 admissions stratified by sex. Analysis by groups of diseases studied. Joinpoints and APC. A: ACVD, men; APC 2001-2015, –1.2 (95%CI, –2.3 to –0.2, P <.05*). B: ACVD, women; APC 2001-2015, –1.2 (95%CI, –2.3 to –0.1, P <.05*). C: AMI, men; APC 2001-2015, –3.3 (95%CI, –4.4 to –2.3, P <.05*). D: AMI, women; APC 2001-2015, –3.2 (95%CI, –4.0 to –1.7, P <.05*). E: unstable angina, men; joinpoint, 2007; APC 2001-2007, 23.0 (95%CI, 7.0-41.3, P <.05*); 2007-2015, –5.0 (95%CI, –13.4 to 4.1, P = 0.2). F: unstable angina, women; joinpoints, 2006 and 2013; APC 2001-2006, 27.9 (95%CI, 14.1-43.5, P <.05*); 2006-2013, 3.7 (95%CI, –3.7 to 11.7, P = 0.3); 2013-2015, –27.5 (95%CI, –57.8 to 24.7, P = 0.3). G: heart failure, men; APC 2001-2015, –1.6 (95%CI, –2.6 to –0.5, P <.05*). H: heart failure, women; APC 2001-2015, –1.0 (95%CI, –2.2 to –0.2, P = 0.1). I: AIS, males; APC 2001-2015, –2.1 (95%CI, –3.6 to –0.6, P <.05*). J: AIS, women; APC 2001-2015, –1.3 (95%CI, –2.7 to –0.3, P <.05*). ACVD, acute cardiovascular disease; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APC, annual percentage change; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval;

, exact annual value. * Statistically significant APC.This study is characterized by 3 novel aspects that have been barely addressed in the Spanish literature. The first aspect is the use of the hospital discharge MBDS. Its analysis transforms data into information that is useful for current health decision-making. The data used refer to the years studied. The use of the MBDS is innovative in that similar information has not been recently published. The second aspect is the type of cross-sectional study, common in epidemiological research, within the clinical setting of discharge from a hospital network. This approach goes beyond mere description. The third aspect is the use of joinpoint regression models, which are very effective in identifying trends and changes in different pathologies over time.

The results show an upward trend in the hospitalization rates of ACVD patients, although there was a statistically nonsignificant transient decrease between 2007 and 2011. These changes would be explained by the total weight of HF cases (47% of the total), which showed a marked increase until 2007 and a more moderate increase until 2015, and by cases of AIS (24% of the total), which showed an upward trend until 2007 followed by a very clear downward trend until 2015, but without reaching statistical significance. By contrast, the hospitalization rates for AMI and unstable angina have decreased since 2003 and 2001, respectively. There was a clear downward trend in hospital mortality rates for ACVDs in general and for each of the diseases studied. These findings coincide with those of recent studies20 and could be of use to indirectly assess the effect of the health and therapeutic measures developed by professional and public health organizations on the detection and control of diseases that trigger these disorders.

Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death worldwide due to noncommunicable diseases,1 and has strong repercussions and economic impacts on society.2–4 Data from the World Health Organization show that total mortality from cardiovascular disease is increasing worldwide as a result of population growth, aging, and certain epidemiological changes in the disease itself.5 The 2013 global burden of disease study, which included data from 188 countries in 21 regions worldwide, showed that in Europe alone had there been a reduction in these diseases. Within Europe, Spain is one of the countries with the lowest incidence and mortality rates. A significant downward trend has been observed in recent years.28 Ischemic heart disease and stroke are the cardiovascular diseases that most contribute to the total burden, and between 1999 and 2010 caused the most deaths and disabilities.6,7

In Spain, circulatory diseases are the leading cause of death, ahead of cancer and respiratory system disease. In descending order, the highest gross death rates/100 000 inhabitants were observed in the Principality of Asturias, Galicia, and Castile and León, although according to data from 2013 there was a decrease in all the autonomous communities.8,9

By individual disease, hospitalization and mortality rates for ischemic heart disease clearly decreased, which was mainly due to a decrease in AMI from 2013 onward. Recently published data report a decrease in the incidence and mortality rates of AMI,21-23,33 which could be related to preventive measures for risk factors, the introduction of troponins in its diagnosis,24 and current treatment strategies.23 The determination of trends in AMI hospitalization and mortality rates is a relevant epidemiological issue because of the modifications that were introduced in its diagnosis in 2000 and 2012.25,34 Prior to the first modification of the definition of AMI, studies published in the United States suggested that its incidence had decreased from 1997 onward.26 However, regarding the decrease in its incidence and mortality rates, other contemporary studies showed that between 1987 and 2006 there had been an epidemiological change that was partly due to the introduction of biomarkers in its diagnosis.25 Nevertheless, a study by Shah et al.35 suggested that, following the implementation in clinical practice of the use of cardiac troponins, there was a higher incidence of AMI or myocardial damage according to the classification of 2012.34 The data obtained in the present study show that there was a change in trends in hospitalization rates from 2003 onward. These data are in line with the positive effect of the measures implemented to prevent this disease and the organizational and treatment changes developed for acute coronary syndrome.36 Nevertheless, the results observed in unstable angina hospitalization and mortality rates deserve special mention, because they show changes that are difficult to interpret except in terms of coding biases or intercenter variability following the modifications to the diagnostic criteria for AMI previously mentioned.

The results show a clear upward trend in the AIS hospitalization rate, which was very marked until 2007. Between 2007 and 2015 the trend changed but without a statistically significant decrease. However, the hospital mortality rate shows a clearly downward trend over the whole period studied. These data are consistent with those published in other settings, which show a decrease in hospitalization rates from the end of the last century to 2009.37 In Spain, AIS is the second cause of death after ischemic heart disease. It is generally associated with factors that increase the risk of mortality although, as a social and health care priority, the development of health care plans for this disease appear to be improving the results.12,14

Finally, the results show that there was a very marked increase in HF hospitalization rates between 2001 and 2007. However, this increase was less pronounced between 2007 and 2015 and was accompanied by a progressive decrease in hospital mortality. HF is one of the most common causes of hospitalization in people older than 65 years. It is a serious public health problem and is considered to be an emerging epidemic. There are few studies on trends in its incidence and survival at discharge. A study published in 2004 showed that the incidence of HF hospitalization had not decreased during the previous 2 decades, although survival had improved.15 These results are in line with those of the present study. Acute HF is one of the main causes of hospitalization and places a severe economic and medical burden on the health system. HF patients have high comorbidity, poor prognosis, and a mortality rate ranging from 4% to 7% at discharge and from 7% to 11% at 2 years.16,38,39

Unstable angina was the only disease in which differences in trends were observed by sex. However, like the overall results, this observation is difficult to interpret but may be due to changes in its diagnosis and coding following the introduction of cardiac troponins. The entity previously diagnosed and codified as angina would now be diagnosed as AMI under the new definition of AMI based on cardiac troponins.3

Cardiovascular disease is expected to increase in the coming years and could cause more than 23 million deaths per year worldwide by 2030. Although the situation in Spain is a cause for concern, it has one of the lowest mortality rates in the world. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, women rank third (50.8 deaths/100 000 inhabitants/y) and men rank eighth (141.5 deaths/100 000 inhabitants/y).11

LimitationsThe data were obtained retrospectively from an administrative registry that was not specifically clinical, and whose coding may have undergone changes over time and in different hospitals. Nevertheless, the study of large databases, such as the MBDS, is a recognized approach to understanding a disease. Finally, unstable angina may have been recorded as AMI due to a progressive but nonuniform application of the changes in the universal definition of AMI.24

CONCLUSIONSIn general, there was an upward trend in ACVD hospitalization rates between 2001 and 2015 in Castile and León, mainly due to HF, but with a decrease in AMI, unstable angina, and AIS. On the other hand, there was a progressive downward trend in ACVD in-hospital mortality rates and for each of the individual diseases. These trends were similar in both sexes.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in Spain. Within this class, ischemic heart disease, HF, and AIS are the leading causes. There is a lack of studies on trends in ACVD hospitalization and hospital mortality rates and the impact of preventive and therapeutic measures. On the other hand, administrative databases such as the MBDS have proved useful for obtaining relevant epidemiological information.

- –

The study of hospital discharges between 2001 and 2015 showed an upward trend in hospitalization rates for ACVD, AMI, unstable angina, HF, and AIS, among which HF was the main cause. There was a downward trend in both sexes in the hospital mortality rate for all these diseases. These results highlight the increasing relevance of these diseases and the potential positive effect of preventive and therapeutic measures.

.

We would like to thank the Directorate General of Public Health and Research, Development, and Innovation of the Ministry of Health of the Junta de Castile and León for facilitating access to the hospital discharge MBDS database.