Heart failure (HF) is a major public health problem, and the prevalence increases with age. In Spain, there are considerable differences between autonomous communities. The aim of this study was to analyze trends in premature mortality due to HF between 1999 and 2013 in Spain by autonomous community.

MethodsWe analyzed data on mortality due to HF in Spanish residents aged 0 to 75 years by autonomous community between 1999 and 2013. Data were collected from files provided by the Spanish Statistics Office. Age-adjusted mortality rates were analyzed and the average annual percentage rate was estimated by Poisson models.

ResultsMortality due to HF represented 10.9% of total mortality. In 2013, the national age-adjusted rate was 2.98 deaths in men and 1.29 deaths in women per 100 000 inhabitants, with an annual mean reduction of 2.27% and 4.53%, respectively. In men, average mortality showed the greatest reduction in Castile-La-Mancha (6.30%). In Cantabria, average mortality significantly increased (3.97%). In women, average mortality showed the greatest decrease in the Chartered Community of Navarre (15.17%).

ConclusionsDuring the study period, mortality due to HF showed an overall average decrease, both nationally and by autonomous community. This decrease was more pronounced in women than in men. Premature mortality significantly decreased in most—but not all—autonomous communities.

Keywords

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in developed countries. After coronary disease and cerebrovascular disease, heart failure (HF) is the third cause of cardiovascular mortality.1–3

Heart failure is a major public health problem. In developed countries it affects 2% of the population, whereas in Spain its prevalence is higher, with percentages ranging from 5% to 6.8%.4,5 There is an exponential increase with age: prevalence is less than 1% before 50 years and more than 10% after 70 years. The increase in prevalence over recent decades is related to the progressive aging of the population, because patients with coronary events have longer survival times.1,2,4,6

Despite improvements in the percentage of patients with HF who receive optimal treatment with drugs,7,8 implantable cardioverter-defibrillators,9 and the treatment of comorbidities,10 the prognosis of this disease remains unfavorable, with high mortality rates7 and hospital readmission rates.11

According to the key indicators of the Spanish National Health System,12 premature mortality (PM) is defined as any death in individuals younger than 75 years,13,14 that is, those occurring before they reach the mean life expectancy at birth. This threshold coincides with that of several causes of avoidable mortality, which have been widely studied in Spain and the European Union.15

To decrease PM, attempts are being made to prevent cardiovascular events at younger ages.16 It is important to understand the health effects of these actions and the mortality trends due to HF by autonomous community in Spain. These data have been previously analyzed, but since then more than 15 years have passed1 and this information needs to be updated.

Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze trends and features of PM due to HF between 1999 and 2013 in Spain as a whole and by autonomous community.

METHODSWe conducted a trend study of PM due to HF between 1999 and 2013 in Spain by autonomous community. Premature mortality was defined as any death due to HF in individuals younger than 75 years. We analyzed data on PM due to HF between 1999 and 2013 in Spanish residents aged between 0 and 74 years by autonomous community. The basic cause of death was defined using the ICD-10 (10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases) I50 codes. Data on deaths and populations were collected from the Spanish Institute of Statistics.17

The direct method was used to calculate the age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR) for each year by autonomous community and sex in 5-year age groups (0-4, 5-9, 10-15, and so on, up to 70-74 years), using the European Standard Population for 2013 as the reference group. The results are shown with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

To assess changes in PM during the study period, Poisson regression models were adjusted to the logarithm of the number of deaths, taking the logarithm of the population as an offset, and adjusting for the age groups less than 50, from 50 to 64, and from 65 to 74 years. The average annual percent change (AAPC) in PM was estimated using the expression (exp (β) – 1) × 100%, where the parameter β corresponds to the variable year of death. The Poisson regression model used to make the adjustment took into account all the years of the study, so that the AAPR was an estimator of changes in mean mortality over the entire period. A 95%CI was calculated for the AAPR and estimated by autonomous community and by sex.

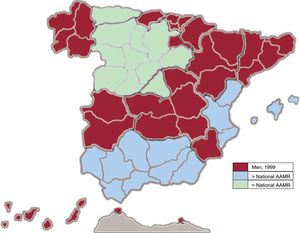

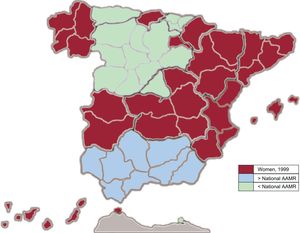

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show maps representing the initial situation in 1999. Areas are shown in which the 95%CI of the AAMR of the corresponding autonomous community excluded the 95%CI of the national AAMR, that is, where there were significant differences at a confidence level of 95%. The maps are simply descriptive and are not intended to identify PM by autonomous community. Each map shows the initial situation in 1999 by sex.

All analyses were conducted using the statistical program R 3.3.1.

RESULTSIn Spain in 1999, there were 2457 premature deaths due to HF (58.4% men and 41.6% female). In 2013, there were 1587 premature deaths due to HF (68.7% men and 31.3% women).

A total of 30 092 premature deaths due to HF were analyzed for the entire study period (61.6% men and 38.4% women). Premature mortality due to HF in individuals younger than 75 years accounted for 10.9% of HF mortality at all ages.

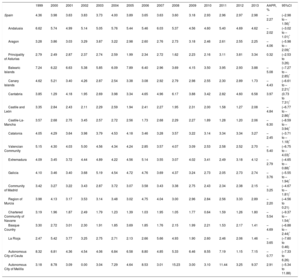

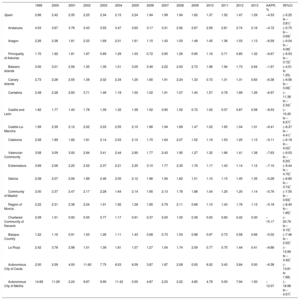

Table 1 and Table 2 show the AAMR for each year, and the AAPC and its 95%CI for the entire period. Each table shows sex-disaggregated data for Spain as a whole and for each autonomous community. show sex-disaggregated data on the number of deaths, the AAMR, and the 95%CIs for each year for Spain as a whole and for each autonomous community.

Age-adjusted Mortality Rates (Direct Method, European Standard Population, 2013) of Premature Mortality Due to Heart Failure in Men (Rate per 100 000 Population) by Year

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | AAPR, % | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 4.36 | 3.98 | 3.63 | 3.83 | 3.73 | 4.00 | 3.89 | 3.65 | 3.63 | 3.60 | 3.18 | 2.93 | 2.96 | 2.97 | 2.98 | –2.27 | (–2.98 to –1.56)* |

| Andalusia | 6.62 | 5.74 | 4.99 | 5.14 | 5.05 | 5.76 | 5.44 | 5.46 | 6.03 | 5.37 | 4.56 | 4.60 | 5.40 | 4.69 | 4.62 | –2.02 | (–3.02 to –1.01)* |

| Aragon | 3.28 | 3.86 | 3.03 | 3.29 | 3.87 | 3.22 | 2.98 | 2.60 | 2.76 | 2.73 | 3.18 | 2.46 | 2.61 | 2.55 | 2.25 | –4.06 | (–5.98 to –2.09)* |

| Principality of Asturias | 2.79 | 2.49 | 2.87 | 2.37 | 2.74 | 2.59 | 1.99 | 2.34 | 2.72 | 1.62 | 2.23 | 2.16 | 3.11 | 3.81 | 3.34 | 0.32 | (–2.53 to 3.26) |

| Balearic Islands | 7.24 | 6.22 | 6.63 | 5.38 | 5.85 | 6.09 | 7.89 | 6.40 | 2.96 | 3.69 | 4.15 | 3.50 | 3.95 | 2.93 | 3.88 | –5.08 | (–7.27 to –2.85)* |

| Canary Islands | 4.62 | 5.21 | 3.40 | 4.26 | 2.87 | 2.54 | 3.38 | 3.08 | 2.92 | 2.79 | 2.98 | 2.55 | 2.30 | 2.89 | 1.73 | –4.43 | (–6.61 to –2.21)* |

| Cantabria | 3.85 | 1.29 | 4.18 | 1.95 | 2.69 | 3.98 | 3.34 | 4.65 | 4.96 | 6.17 | 3.88 | 3.42 | 2.82 | 4.60 | 6.58 | 3.97 | (0.73 to 7.31)* |

| Castile and León | 3.35 | 2.84 | 2.43 | 2.11 | 2.29 | 2.59 | 1.94 | 2.41 | 2.27 | 1.95 | 2.31 | 2.00 | 1.58 | 1.27 | 2.08 | –4.84 | (–6.77 to –2.86)* |

| Castile-La-Mancha | 3.57 | 2.68 | 2.75 | 3.45 | 2.57 | 2.72 | 2.56 | 1.73 | 2.68 | 2.29 | 2.27 | 1.89 | 1.28 | 1.20 | 2.06 | –6.30 | (–8.59 to –3.94)* |

| Catalonia | 4.05 | 4.29 | 3.64 | 3.98 | 3.79 | 4.53 | 4.18 | 3.46 | 3.28 | 3.57 | 3.22 | 3.14 | 3.34 | 3.34 | 3.27 | –2.45 | (–3.71 to –1.18)* |

| Valencian Community | 5.15 | 4.30 | 4.03 | 5.00 | 4.56 | 4.34 | 4.24 | 2.85 | 3.57 | 4.07 | 3.09 | 2.53 | 2.58 | 2.52 | 2.70 | –5.40 | (–6.75 to –4.03)* |

| Extremadura | 4.09 | 3.45 | 3.72 | 4.44 | 4.89 | 4.22 | 4.56 | 5.14 | 3.55 | 3.07 | 4.02 | 3.41 | 2.49 | 3.18 | 4.12 | –2.79 | (–4.65 to –0.88)* |

| Galicia | 4.10 | 3.46 | 3.40 | 3.68 | 5.19 | 4.54 | 4.72 | 4.76 | 3.69 | 4.37 | 3.24 | 2.73 | 2.05 | 2.73 | 2.74 | –3.76 | (–5.55 to –1.94)* |

| Community of Madrid | 3.42 | 3.27 | 3.22 | 3.43 | 2.87 | 3.72 | 3.07 | 3.58 | 3.43 | 3.38 | 2.75 | 2.43 | 2.34 | 2.38 | 2.15 | –3.25 | (–4.67 to –1.81)* |

| Region of Murcia | 3.98 | 4.13 | 3.17 | 3.53 | 3.14 | 3.48 | 3.02 | 4.75 | 4.04 | 3.00 | 2.96 | 2.84 | 2.56 | 3.33 | 2.89 | –2.20 | (–4.56 to 0.21) |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 3.19 | 1.96 | 1.87 | 2.49 | 1.79 | 1.23 | 1.39 | 1.03 | 1.95 | 1.05 | 1.77 | 0.64 | 1.59 | 1.26 | 1.80 | –5.54 | (–9.37 to –1.54)* |

| Basque Country | 3.30 | 2.72 | 3.01 | 2.30 | 1.91 | 1.85 | 3.69 | 1.85 | 1.76 | 2.15 | 1.99 | 2.21 | 1.53 | 2.17 | 1.41 | –4.69 | (–6.88 to –2.44)* |

| La Rioja | 2.47 | 5.42 | 3.77 | 3.25 | 2.75 | 2.71 | 2.13 | 2.66 | 5.66 | 4.93 | 1.90 | 2.60 | 2.46 | 2.06 | 1.46 | –3.65 | (–7.60 to 0.46) |

| Autonomous City of Ceuta | 8.32 | 6.81 | 4.36 | 4.54 | 4.06 | 6.84 | 6.58 | 8.80 | 4.85 | 5.33 | 6.46 | 8.55 | 7.19 | 1.15 | 7.15 | –0.77 | (–7.33 to 6.26) |

| Autonomous City of Melilla | 3.18 | 8.78 | 3.09 | 0.00 | 3.04 | 7.29 | 4.64 | 8.53 | 3.01 | 15.23 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 11.44 | 3.25 | 9.37 | 2.91 | (–5.34 to 11.88) |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AAPR, average annual percentage rate.

Age-adjusted Mortality Rates (Direct Method, European Standard Population, 2013) of Premature Mortality Due to Heart Failure in Women (Rate per 100 000 Population) by Year

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | AAPR, % | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 2.66 | 2.42 | 2.35 | 2.25 | 2.34 | 2.15 | 2.24 | 1.94 | 1.99 | 1.94 | 1.62 | 1.37 | 1.52 | 1.47 | 1.29 | –4.53 | (–5.25 to –3.81)* |

| Andalusia | 4.53 | 3.67 | 3.76 | 3.43 | 3.55 | 3.47 | 3.60 | 3.17 | 3.31 | 2.92 | 2.67 | 2.59 | 2.81 | 2.74 | 2.16 | –4.72 | (–5.75 to –3.69)* |

| Aragon | 2.26 | 2.38 | 1.81 | 2.33 | 1.69 | 2.01 | 1.61 | 1.15 | 1.43 | 1.03 | 1.48 | 1.45 | 1.36 | 1.03 | 1.13 | –6.59 | (–9.04 to –4.08)* |

| Principality of Asturias | 1.70 | 1.92 | 1.81 | 1.87 | 0.89 | 1.29 | 1.03 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 1.26 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 1.32 | –6.67 | (–9.53 to –3.72)* |

| Balearic Islands | 3.00 | 3.01 | 2.56 | 1.35 | 1.39 | 1.01 | 3.05 | 3.46 | 2.22 | 2.00 | 2.73 | 1.96 | 1.94 | 1.73 | 2.64 | –1.67 | (–4.51 to 1.25) |

| Canary Islands | 2.73 | 2.28 | 2.55 | 1.39 | 2.02 | 2.34 | 1.25 | 1.80 | 1.91 | 2.24 | 1.33 | 0.72 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 0.83 | –6.38 | (–9.56 to –3.08)* |

| Cantabria | 2.48 | 2.28 | 2.83 | 3.71 | 1.46 | 1.18 | 1.50 | 1.02 | 1.91 | 1.07 | 1.40 | 1.57 | 0.78 | 1.89 | 1.26 | –6.97 | (–11.38 to –2.34)* |

| Castile and León | 1.82 | 1.77 | 1.43 | 1.78 | 1.39 | 1.32 | 1.39 | 1.52 | 0.90 | 1.52 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.37 | 0.87 | 0.58 | –8.53 | (–10.45 to –6.57)* |

| Castile-La-Mancha | 1.99 | 2.39 | 2.12 | 2.02 | 2.03 | 2.55 | 2.10 | 1.86 | 1.94 | 1.69 | 1.47 | 1.02 | 1.65 | 1.04 | 1.01 | –6.41 | (–8.37 to –4.41)* |

| Catalonia | 2.58 | 1.89 | 1.82 | 1.81 | 2.14 | 2.03 | 2.10 | 1.70 | 1.64 | 2.07 | 1.52 | 1.19 | 1.53 | 1.25 | 1.13 | –5.11 | (–6.18 to –4.02)* |

| Valencian Community | 3.08 | 3.09 | 3.00 | 2.94 | 3.41 | 2.44 | 2.90 | 1.77 | 2.43 | 1.95 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 1.66 | 1.41 | 1.38 | –7.63 | (–9.03 to –6.20)* |

| Extremadura | 3.69 | 2.06 | 2.20 | 2.52 | 2.37 | 2.21 | 2.25 | 3.10 | 1.77 | 2.35 | 1.76 | 1.17 | 1.43 | 1.14 | 1.12 | –7.10 | (–9.44 to –4.70)* |

| Galicia | 2.08 | 2.07 | 2.06 | 1.89 | 2.46 | 2.05 | 2.12 | 1.96 | 1.94 | 1.62 | 1.51 | 1.10 | 1.15 | 1.45 | 1.35 | –5.28 | (–6.80 to –3.74)* |

| Community of Madrid | 2.00 | 2.37 | 2.47 | 2.17 | 2.28 | 1.64 | 2.14 | 1.85 | 2.13 | 1.78 | 1.88 | 1.04 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.14 | –5.76 | (–7.55 to –3.93)* |

| Region of Murcia | 2.22 | 2.31 | 2.36 | 2.24 | 1.91 | 1.92 | 1.28 | 1.85 | 2.79 | 2.11 | 0.68 | 1.10 | 1.43 | 1.76 | 1.13 | –5.18 | (–8.40 to –1.85)* |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 2.08 | 1.51 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 1.17 | 0.91 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.00 | –15.17 | (–20.79 to –9.15)* |

| Basque Country | 1.22 | 1.16 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 1.11 | 1.43 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.66 | –5.02 | (–7.46 to –2.52)* |

| La Rioja | 2.42 | 3.78 | 2.98 | 1.01 | 1.39 | 1.81 | 1.07 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 1.74 | 2.59 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 1.44 | 0.41 | –8.86 | (–13.99 to –3.42)* |

| Autonomous City of Ceuta | 2.00 | 2.09 | 4.00 | 11.60 | 7.75 | 6.03 | 6.09 | 3.87 | 1.87 | 2.08 | 0.00 | 6.02 | 3.43 | 3.84 | 0.00 | –6.38 | (–13.81 to 1.68) |

| Autonomous City of Melilla | 14.68 | 11.29 | 2.24 | 9.87 | 9.90 | 11.42 | 0.00 | 4.87 | 2.23 | 2.22 | 4.85 | 4.78 | 0.00 | 7.94 | 1.50 | –12.07 | (–18.98 to –4.57)* |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AAPR, average annual percentage rate.

In 1999, the Spanish national AAMR was 4.36/100 000 in men and 2.66/100 000 in women (henceforth, rates per 100 000 population). In 2013, the AAMR for HF was 2.98 in men and 1.29 in women. Over the entire period, there was a reduction of the AAPC of 2.27% in men and 4.53% in women.

In 1999, the autonomous communities with the most and the least PM in men (Table 1) were the Balearic Islands (AAMR, 7.24) and La Rioja (AAMR, 2.47), respectively. In 2013, the autonomous communities with the most and the least PM in men were Cantabria (AAMR, 6.58) and the Basque Country (AAMR, 1.41), respectively. There was a significant mean reduction in PM in all the autonomous communities, except in the Principality of Asturias, the Region of Murcia, La Rioja, the Autonomous City of Ceuta, and the Autonomous City of Melilla. In Cantabria there was a significant increase in the mean PM (AAPR 3.97%; 95%CI, 0.73-7.31). The greatest mean reduction in PM during the study period was in Castile-La-Mancha (AAPR−6.30; 95%CI,−8.59 to−3.94).

In 1999, the autonomous communities with the most and the least PM in women (Table 2) were Andalusia (AAMR, 4.53) and the Basque Country (AAMR, 1.22), respectively. In 2013, the autonomous communities with the most and the least PM were the Balearic Islands (AAMR, 2.64) and the Chartered Community of Navarre (AAMR, 0.00), respectively. There was a significant mean reduction in PM in all the autonomous communities, and a nonsignificant mean reduction in the Balearic Islands and the Autonomous City of Ceuta. The greatest reduction of PM in the study period was in the Chartered Community of Navarra (AAMR 0.00; AAPC−15.17, 95%CI,−20.79 to−9.15).

The Autonomous City of Ceuta and the Autonomous City of Melilla showed wide variability in the AAMR estimates. In the latter city, the AAMR varied from 0 to 15.23 in men and from 0 to 14.68 women over the study period. In both cities there was also high variability in the AAPC but without reaching statistical significance.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the autonomous communities with the significantly highest and lowest AAMRs compared with the national AAMR by sex. Table 1 and Table 2 show the AAPR of each autonomous community by sex.

The map for 1999 shows a slight northwest-southeast distribution in PM in men, and lower PM in the north than in the south compared with national PM (Figure 1). Table 1 shows that there was an overall mean decrease in PM over the study period by autonomous community, except for the significant mean increase in Cantabria. The autonomous communities with the lowest mean decrease were Andalusia, Extremadura, and Catalonia.

The map for 1999 shows a slight north-south distribution in PM in women, similar to that of men, with higher mortality in Andalusia and lower mortality in Castile and León, the Community of Madrid, the Principality of Asturias, and the Basque Country compared with the national AAMR. Table 2 shows that there was an overall mean decrease in PM throughout Spain, with marked mean improvements in Castile and León, La Rioja, the Chartered Community of Navarre, and the Autonomous City of Melilla, followed by Extremadura and the Valencian Community. The overall mean decrease did not reach statistical significance in the Autonomous City of Ceuta and the Balearic Islands.

that show trends in the AAMR for Spain and for each autonomous community by year and sex. In general, the AAMR in men remained stable in all the autonomous communities over the study period. It is noteworthy that there were peaks in the Balearic Islands in 2005 and in La Rioja in 2007. In Cantabria, there was a mean increase in PM, although this increase was subject to fluctuations.

The AAMR was more stable in women than in men in the autonomous communities. In addition, the mean decrease in PM was more pronounced in women than in men. The data show that there was great variability in both men and women in the Autonomous City of Ceuta and the Autonomous City of Melilla.

DISCUSSIONThis study shows that there has been an overall decrease in mean PM due to HF in Spain as a whole and in each autonomous community. This decrease was more marked in women than in men. In the study period, there was a significant mean increase in PM in men in Cantabria.

Despite significant interregional differences, the data obtained on PM in Spain are in line with those reported by Boix Martínez et al.1 on mortality due to HF from 1977 to 1998. In that period, PM was concentrated in the southern and south-eastern regions of peninsular Spain, the Balearic Islands, the Autonomous City of Ceuta, and the Autonomous City of Melilla. However, the present study shows that, from 1999 to 2013, the unequal north-south distribution by autonomous community was less marked, and that there was an overall improvement in the PM rates in both sexes. This overall improvement was more significant in Castile-La-Mancha, the Chartered Community of Navarre, and the Valencian Community and, in the case of women, in La Rioja, the Chartered Community of Navarre, and Castile and León. In addition, there was a mean increase in PM in men in Cantabria from 1999 to 2013.

There was a striking overall mean decrease in PM in women throughout Spain, which was twice that in men. The high interannual variability in PM observed in the Autonomous City of Ceuta and the Autonomous City of Melilla could be due to the small size of the population in these cities and the small number of cases, making it difficult to compare trends. Some of the AAMR estimates have a zero value in specific geographic areas, because no deaths for that specific sex were recorded that year in that area. A possible explanation could be that, by using a cutoff of 75 years, only 10.9% of the mortality due to HF was analyzed.

A French study conducted in 2012 on mortality trends in Europe in the last 20 years (1987-2008) also found a significant decrease of 40% in mortality rates (54.2-32.6).2 Spain was one of the countries showing a major decrease. The decrease in mortality was also larger in women (P<.0001).

The EUROASPIRE III study18 compared gender-related lifestyle changes and risk factor management after hospitalization for a coronary event or revascularization. In contrast to subsequent studies, it was found that control of cardiovascular risk factors was worse in women than in men. This finding was in line with those of previous studies. However, the EUROASPIRE IV study19 found that age and educational level in both sexes had an influence on the control of cardiovascular risk factors. The greatest differences between sexes were observed in less educated and elderly patients.

Given that HF is a major public health problem, the INCARGAL20 (2003), EPISERVE21 (2008), and INCA22 (2009) studies, among others,23–27 aimed to characterize the clinical profile and diagnostic and therapeutic treatment of HF, highlighting the differences between specialists in the management of HF, as well as the low percentage of patients who had been treated according to clinical practice guidelines. These studies drew attention to the need for an educational and multidisciplinary approach in the outpatient care of patients with HF. Since then, the overall mean decrease in PM observed in the present study reinforces the hypothesis of improvements in primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention in recent years, and an improvement in the treatment of acute HF in emergency and intensive care medicine services, which make greater use of evidence-based medicine and apply the clinical guidelines in practice. Thus, despite the increased prevalence of HF, there is now better control of this disease and a decrease in PM due to HF; nevertheless, current results still need to be improved.

New treatment strategies have been developed, such as HF clinics, which provide teams comprising nursing staff, primary care physicians, and primary care specialists, who pay very close attention to patients and make use of clinical pathways. These types of clinic have been shown to improve prognosis and reduce PM in patients with HF. The Spanish multicenter PRICE study28 found very significant reductions in HF admissions of patients treated in HF units, demonstrating improved prognosis with survival rates of 90% per year and 83% at 2 years.

A study by Anguita Sánchez et al.29 published in 2004 analyzed the clinical characteristics, treatment, and morbidity and mortality of 3909 patients with HF attending 62 HF clinics participating in the BADAPIC registry (a database of patients with HF in Spain) in the previous 3 years. The study showed that the treatment received by patients with HF attending HF clinics or HF units closely approached the diagnostic and treatment standards recommended for patients with HF. Regarding the characteristics of these units, 29% had a full-time trained nurse, 13% had common protocols with their primary care areas with established criteria and referral routes, but only 5% had home healthcare programs. Half of the units had facilities for free telephone consultations or access to the unit without prior need for appointment. 84% only had cardiologists, whereas the other units also had internists, geriatricians, psychologists, and social workers.

A Swedish study30 found that follow-up at a nurse-led HF clinic reduced 1-year mortality from 37% to 13% (P=.005). The PRICE study, BADAPIC registry, and the Swedish study showed that the annual mortality rates ranged from 5% to 10%. These figures are very different from the annual mortality rates of 20% to 30% reported in population registries, but are similar to those of clinical trials. Thus, these 3 studies showed that the care of patients with HF in specialized units or clinics can improve prognosis.28–30

Causes of the decrease in PM due to HF include: a) the decrease in the incidence of HF, although the increased prevalence of hypertension and its lack of control, and greater survival after myocardial infarction would tend to lead to an increase rather than to a decrease; b) improvements in the treatment of patients, because HF is a disease that is not only very susceptible to pharmacological treatment, but is particularly susceptible to the adequate use of diuretics; however, other interventions, such as telemedicine, have also been experimentally tested with excellent results, and the treatment of ischemic heart disease, which is a main cause of HF, has led to recent improvements; and c) delays in the appearance of symptoms in young people, in whom symptoms could be more masked, could be a cause of lack of diagnosis and of the recording of HF as the cause of death.

Currently, there are new therapeutic targets31,32 in the treatment of HF that, if effective, could contribute to reducing mortality in the near future.

LimitationsA limitation of this study is possible competitive risk with other conditions such as cancer or cerebrovascular disease, although mortality due to these diseases has decreased in the period analyzed. Another limitation is variability between autonomous communities in coding the basic cause of death, although standardized coding methods are employed. Finally, the basic cause of death could be distorted by the high comorbidity at advanced ages, although the present study used 75 years as the cutoff for PM.

Further studies on PM in this study period are needed in smaller areas, such as municipalities or census districts, to identify more specific patterns of PM due to HF.

CONCLUSIONSThis study found an overall mean decrease in PM due to HF in Spain as a whole and in the autonomous communities. This decrease was more marked in women. During the study period, there was a significant mean increase in PM in men in Cantabria. Despite the overall decrease in PM, these results could still be improved by decreasing the observed differences between autonomous communities.

Primary and secondary prevention in individuals younger than 75 years reduces the number of cardiovascular events at older ages and thus decreases PM due to HF.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Heart failure is a major public health problem. In Spain, its prevalence ranges from 5% to 6.8%. Prognosis remains unfavorable in the mid-term. There are marked geographical differences in PM, with a north-south distribution profile.

- –

Between 1999 and 2013, there was an overall mean decrease in PM due to HF in Spain as a whole and in the autonomous communities. This decrease was more marked in women. Prevention at an early age reduces the number of cardiovascular events and thus decreases premature or avoidable deaths due to HF.