Heart failure (HF) remains a severe cardiovascular disease with increasing prevalence and high morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 There is an unmet need to improve prognosis and reduce the socioeconomic impact of HF management.2 In addition to pharmaceutical regimens and interventions, lifestyle measures tailored to the underlying causes of HF exacerbations may help to achieve these goals. Among the precipitating factors for HF worsening, respiratory infections play a leading role.3 The underlying pathogenic organisms of respiratory infections are predominantly influenza viruses and pneumococcal bacteria.4 Currently, a purely causative relationship between HF and influenza and/or pneumococcal infection has not been proven. However, frequent, infection-induced HF exacerbations that follow a seasonal, periodic fashion imply an association between those organisms and the development and progression of HF.5

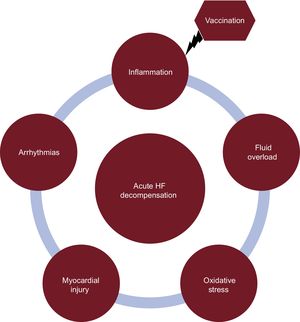

INFLUENZA VACCINATION AND HEART FAILUREInfluenza vaccination is an effective measure to reduce all-cause mortality among high-risk persons during seasonal influenza epidemics.6 The high-risk population includes mostly elderly individuals with significant comorbidities predisposing them to respiratory infection. Most but not all community-based studies support the timely implementation of anti-influenza vaccination for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in high-risk populations.7 Patients with already established cardiovascular disease may also benefit from anti-influenza vaccination.8 The studies performed to date might have been biased by unmeasured confounders and study population variance, leading to the aforementioned discrepancies.9 The underlying pathogenetic mechanisms of HF exacerbations during infections may involve direct myocardial injury, inflammation, and fluid shifts. However, they remain mostly speculative. In this context, a cause-effect relationship between vaccination and reduced morbidity and mortality is missing10,11 (Figure).

In HF patients, anti-influenza vaccination confers considerable benefits regarding the frequency and severity of HF exacerbations,12 especially when other comorbidities coexist.13 It is well-known that patients at higher risk derive greater benefit from vaccination.14 Thus, HF patients, who have multiple comorbidities, are expected to gain more cardioprotection from anti-influenza vaccination. In a large (59 202 HF patients), self-controlled case series study, the anti-influenza vaccination was associated with a lower hospitalization rate for cardiovascular diseases.15 Regarding the seasonal epidemics of respiratory infections, the initial concept for vaccination in HF patients was to provide protection only during the influenza season (December to April). However, a growing body of evidence underpinned a persistent reduction in hospitalization of vaccinated HF patients throughout the year,16 not only during the “flu season”, as previously reported.9 This is an extremely important finding, since it emphasizes the role of immunity on HF progression and supports immunization strategies throughout the year. Most importantly, there is accumulated data from population-based studies, documenting survival benefits in anti-influenza vaccinated heart failure patients.16,17 A subanalysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial, which was designed to assess the efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril in patients with symptomatic HF and reduced ejection fraction (< 40%), outlined the important contribution of vaccination on survival after a median follow-up of 27 months.18 Independently of other confounders, anti-influenza vaccination determined survival in the propensity adjusted models.

PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINATION AND HEART FAILUREPneumococcal disease is common among older adults. A growing body of evidence supports the association of pneumococcal pneumonia and HF development.19 Patients admitted to hospital with pneumococcal pneumonia frequently have concurrent acute myocardial infarction or new/worsening HF.20 Conversely, pneumococcal vaccination reduces the incidence of pneumonia and seems to lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in older individuals.21 To our knowledge there is no study assessing solely antipneumococcal vaccination in an HF cohort. For instance, a recent multicenter study demonstrated lower 30-day and 1-year mortality in HF patients who received the recommended care including medications and vaccinations (influenza and pneumococcal).22 Unambiguously, the immunogenicity and safety of different antipneumococcal vaccination types and doses requires further investigation.23 Thus, there is a shortage of robust evidence about the efficacy of antipneumococcal vaccination in the HF population.

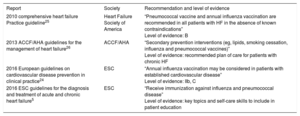

COMMENTSBoth European and American cardiology societies recommend immunization against influenza and pneumococcal infection in the context of patients’ skills and professional behaviors. In particular, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has recently “advised both vaccines on local guidance and immunization practice”.5 In the ESC guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention, “annual influenza vaccination may be considered in patients with established cardiovascular disease” (level of evidence: IIb, C).24 However, as the authors declared, that recommendation is primarily focused on acute myocardial infarction prevention. In the Heart Failure Society of America guidelines, pneumococcal vaccination and annual influenza vaccination were recommended in 2010 in all HF patients (level of evidence: B).25 In 2013, the American Heart Association also recommended influenza and pneumococcal vaccination among secondary prevention interventions.26 Notably, those recommendations were based on expert consensus, since there are no randomized controlled trials and the evidence derives from large, observational studies or population-based registries, which have mostly enrolled patients with cardiovascular disease. Last but not least, immunization has been listed among the key topics and self-care skills in the recent recommendations of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC5 (Table).

Guideline Recommendations of the International Cardiology Societies on Anti-influenza and Antipneumococcal Vaccination in the Heart Failure Population

| Report | Society | Recommendation and level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 comprehensive heart failure Practice guideline25 | Heart Failure Society of America | “Pneumococcal vaccine and annual influenza vaccination are recommended in all patients with HF in the absence of known contraindications” Level of evidence: B |

| 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines for the management of heart failure26 | ACCF/AHA | “Secondary prevention interventions (eg, lipids, smoking cessation, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines)” Level of evidence: recommended plan of care for patients with chronic HF |

| 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice24 | ESC | “Annual influenza vaccination may be considered in patients with established cardiovascular disease” Level of evidence: IIb, C |

| 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure5 | ESC | “Receive immunization against influenza and pneumococcal disease” Level of evidence: key topics and self-care skills to include in patient education |

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HF, heart failure.

Therefore, the available data suggest the advisability of vaccination in the HF population but they have not been validated and systematically analyzed. On the other hand, it seems unethical to apply a large, blind, randomized, controlled trial in order to test vaccination efficacy in HF patients, as it would require a sample without vaccination. Moreover, the necessary dosage of effective vaccines needs further investigation. There is an ongoing, clinical trial (NCT02787044)27 aiming at the comparative evaluation of the high dose trivalent influenza vaccine vs standard dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine in high-risk cardiovascular patients, such as those with recent myocardial infarction or HF hospitalization. In parallel, the wide variety in vaccination rates in different countries constitutes another important issue of health care systems. The PARADIGM-HF trial and other registries have documented higher vaccination rates in developed rather than undeveloped countries. Hence, several aspects should be clarified to obtain robust evidence that will support a wide recommendation of vaccination in HF population.28

CONCLUSIONSBoth influenza and pneumococcal infection are associated with high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Vaccination against these infections seems to be a cost-effective, preventive measure, improving survival and reducing cardiovascular events in high-risk populations, such as those with HF. However, large-scale trials are required to clarify the safety and efficacy of anti-influenza and antipneumococcal vaccinations in HF conditions.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. Parissis received horonaria for lectures from Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Servier and Pfizer.

.

N.P.E. Kadoglou was granted a clinical fellowship by the European Heart Rhythm Association.