Very early (1-3 months) discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) has been recently proposed in percutaneous coronary interventions with modern drug-eluting stents (DES), with contrasting results. The aim of the present meta-analysis was to evaluate the prognostic impact of very short DAPT regimens vs the standard 12-month regimen in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with new DES.

MethodsLiterature and main scientific session abstracts were searched for randomized clinical trials (RCT). The primary efficacy endpoint was mortality, and the primary safety endpoint was major bleeding events. A prespecified analysis was conducted according to the long-term antiplatelet agent.

ResultsWe included 5 RCTs, with a total of 30 621 patients; 49.97% were randomized to very short (1-3 months) DAPT, followed by aspirin or P2Y12I monotherapy. Shorter DAPT duration significantly reduced the rate of major bleeding (2% vs 3.1%, OR, 0.62; 95%CI, 0.46-0.84; P=.002; Phet=.02), but did not significantly condition overall mortality (1.3% vs 2%, OR, 0.97; 95%CI, 0.73-1.29; P=.84; Phet=.18). The reduction in bleeding events was even more significant in trials randomizing event-free patients at the time of DAPT discontinuation. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis was similar between shorter vs standard 12-month DAPT.

ConclusionsBased on the current meta-analysis, a very short (1-3 months) period is associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding compared with the standard 12-month therapy, with no increase in major ischemic events and comparable survival.

Keywords

Due to improved stent technology, a progressive decrease in stent thrombosis has occurred.1,2 In addition, the reduction in recurrent ischemic events produced by the application of more aggressive preventive pharmacological measures, including lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive medications3–6 has warranted reconsideration of the role of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with modern drug-eluting stents (DES).

Progressive shortening of the optimal DAPT duration has been recommended in guidelines,7,8 currently indicating 6-month DAPT in chronic coronary disease, while maintaining the standard 12-month duration in acute settings. However, population aging and the increased proportion of patients at high risk for bleeding events has encouraged investigation into a further reduction in DAPT duration (1-3 months) especially in particular subsets of patients with a low ischemic profile.9,10

Since aspirin has been reported to be the major determinant of gastrointestinal bleeding complications,11 several studies12–14 have addressed the option of discontinuing aspirin after a very short DAPT period, continuing with P2Y12I monotherapy thereafter. Indeed, the reassuring results of the WOEST trial12 have been limited by the inclusion of a selected population, 30% of whom had bare metal stents, were at high risk for bleeding events and required anticoagulation with clopidogrel. However, the introduction of more potent antiplatelet agents, such as ticagrelor, potentially providing per se adequate platelet inhibition, has led recent trials to evaluate a strategy of early aspirin discontinuation and long-term ticagrelor.14

Therefore, the aim of the present meta-analysis was to evaluate the prognostic impact of different regimens of very short DAPT compared with a standard 12-month treatment in patients undergoing PCI with modern DES.

METHODSEligibility and search strategyThe literature was scanned by formal searches of electronic databases (MEDLINE, Cochrane, and EMBASE) for clinical studies and scientific session abstracts, oral presentations, and/or expert slide presentations from January 2008 to October 2019. The following key words were used: “dual antiplatelet therapy”, “duration”, “clopidogrel”, “prasugrel”, “ticagrelor”, “drug-eluting stent”, “randomized”.

No language restrictions were applied. Inclusion criteria were as follows: a) studies comparing very short (< 6 months) durations of DAPT treatment vs a standard 12-month strategy; b) invasive management of patients with PCI; c) use of new generation DES in more than 90% of the patients; d) availability of complete clinical and outcome data. Exclusion criteria were as follows: a) follow-up data in less than 90% of patients; b) use of old generation DES (Cypher, Taxus, Endeavor); and c) ongoing studies or irretrievable data. The final selection of included trials was made by individual screening of the potential full-length articles, independent assessment of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and risk of bias by 2 investigators, and final inclusion in the meta-analysis of the eligible studies.

Data extraction and validity assessmentData were independently abstracted by 2 investigators (M. Verdoia, G. De Luca). If the data were incomplete or unclear, the authors were contacted. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data were managed according to the intention-to-treat principle. The Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition of major bleedings was preferred, when reported.15

Outcome measuresThe primary efficacy endpoint was overall mortality at 12 months’ follow-up. The primary safety endpoint was the rate of major bleeding complications (according to protocol definition).

Secondary endpoints were: a) recurrent myocardial infarction, and b) ST (definite or probable according to Academic Research Consortium-ARC definition).

Data analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager 5.3 freeware package, SPSS 23.0 statistical package and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA, IBM Statistics). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were used as summary statistics. The pooled OR was calculated by using a random effect model (Mantel-Haenszel). The Breslow-Day test was used to examine the statistical evidence of heterogeneity across the studies (P <.1). Study quality was evaluated by the same 2 investigators according to a previously described score whose criteria are detailed in .3 The risk of bias across studies was calculated using the CMA package. In particular, potential publication bias was examined by constructing a funnel plot, in which the sample size was plotted against ORs (for the primary endpoint). In addition, the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials was also applied to assess the risk of bias, by generating a classification table for each study according to the different types of bias. A meta-regression analysis was carried out according to the rate of acute coronary syndrome patients enrolled in the studies.

A sensitivity analysis was performed according to time to randomization (at the time of PCI or at DAPT discontinuation). The study was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.16

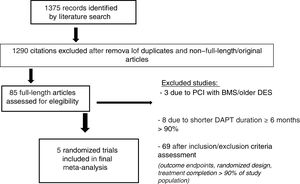

RESULTSEligible studiesOf 1375 citations, 16 trials were initially identified.13–15,17–29 Three trials were excluded because they allowed treatment with BMS or older DES19–21 and 8 trials were excluded because the shortest DAPT period was 6 months.22–29 Therefore, 5 randomized clinical trials were finally included with a total of 30 621 patients13–15,17,18 (figure 1). A total of 3 trials14,17,18 evaluated the benefits of a shorter, 3-month DAPT regimen (5801 patients randomized to 3 months and 5807 patients to 12 months), whereas 2 trials13,15 further lowered the duration of DAPT to 1 month.

The antiplatelet agents used for the DAPT regimen were aspirin and clopidogrel (75mg/d) or ticagrelor (90mg bid), with prasugrel (10mg/d) being allowed in 3 trials.15,17,18 Maintenance antiplatelet therapy from DAPT discontinuation to 12 months was performed with aspirin in 1 study,17 ticagrelor in 2 trials,13,14 and any P2Y12I in 2 randomized clinical trials.15,18

The study characteristics of included trials are shown in table 1. Follow-up duration ranged from 1 year (in 3 trials) to 2 years,13,14 although data at 12 months were considered in all the studies.

Characteristics of included randomized studies

| Study | Publication | Type | Antiplatelet treatment | Time to randomization | Inclusion | Exclusion | Quality score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategyshorter DAPT | Months | Strategylonger DAPT | Months | |||||||

| GLOBAL LEADERS13 | 2018 | Multicenter, RCT | Ticagrelor (90mg bid) alone for 23 mo | 1 | Aspirin (75-100mg qd)+ticagrelor (90mg bid) for 11 mo or clopidogrel (75mg qd) then aspirin alone | 12 | At index PCI | 1. Patients scheduled to undergo PCI for stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndromes | Oral anticoagulation indicated | 10 |

| SMART-CHOICE18 | 2019 | Multicenter, RCT | Clopidogrel 75mg qd or prasugrel 10mg qd, or ticagrelor 90mg bid | 3 | Aspirin 100mg qd+clopidogrel 75mg qd or prasugrel 10mg qd or ticagrelor 90mg bid | 12 | At 3 mo | 1. Age 20 years or older; 2. 1 or more stenosis of 50% or more in a native coronary artery with visually estimated diameter of 2.25mm or greater and 4.25mm or smaller amenable to stent implantation, 3. Patients who have undergone PCI | 1. Known hypersensitivity or contraindication to aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor, everolimus, or sirolimus; 2. Hemodynamic instability or cardiogenic shock; 3. Active pathologic bleeding; 4. Drug-eluting stent implantation within 12 mo before the index procedure; 5. Women of childbearing potential; noncardiac comorbid conditions | 10 |

| STOPDAPT-215 | 2019 | Multicenter, RCT | Clopidogrel 75mg qd | 1 | Aspirin+clopidogrel 75mg qd | 12 | At 1 mo | 1. PCI with exclusive use of CoCr-EES; 2. No major complications during hospitalization for index PCI; 3. No plan for staged PCI; 4. Patients who could take DAPT with aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors | With a life expectancy less than 2 years; 6. Conditions that may result in protocol nonadherence | 9 |

| TWILIGHT14 | 2019 | Multicenter, RCT | Ticagrelor (90mg bid) | 3 | Ticagrelor (90mg bid) and enteric-coated aspirin (81-100mg qd) | 12 | At 3 mo | High-risk patients who have undergone successful PCI with at least 1 locally approved drug-eluting stent discharged on DAPT with aspirin and ticagrelor for at least 3 mo | 1. Need for oral anticoagulants; 2. History of intracranial hemorrhage | 10 |

| REDUCE17 | 2019 | Multicenter, RCT | Aspirin+prasugrel, ticagrelor (preferred over clopidogrel) | 3 | Aspirin+prasugrel, ticagrelor (preferred over clopidogrel) | 12 | Before discharge for index PCI | 1. ACS patients undergoing successful COMBO stent implantation | 1. Recent major bleeding; 2. Contraindication to DAPT; 3. Revascularization with other stent type; 4. Need for permanent DAPT due to comorbidities | 10 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; bid, bis in diem, CoCr-EES, cobalt chromium everolimus-eluting stent; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI, percutaneous coronary interventions; qd, quid diem; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

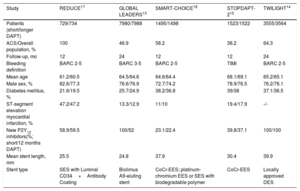

Table 2 displays the characteristics of enrolled patients. The mean age was 64.7±2.7 years, 77.4% were male, 32.3% were diabetic, and 61.5% of patients had acute coronary syndrome (100% in 1 trial17). New-generation DES were used in most patients (100% in 4 randomized clinical trials, 97.8% in 1 study14).

Clinical features of patients in included studies

| Study | REDUCE17 | GLOBAL LEADERS13 | SMART-CHOICE18 | STOPDAPT-215 | TWILIGHT14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (short/longer DAPT) | 729/734 | 7980/7988 | 1495/1498 | 1523/1522 | 3555/3564 |

| ACS/Overall population, % | 100 | 46.9 | 58.2 | 38.2 | 64.3 |

| Follow-up, mo | 12 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Bleeding definition | BARC 2-5 | BARC 3-5 | BARC 2-5 | TIMI | BARC 2-5 |

| Mean age | 61.2/60.5 | 64.5/64.6 | 64.6/64.4 | 68.1/69.1 | 65.2/65.1 |

| Male sex, % | 82.6/77.3 | 76.6/76.9 | 72.7/74.2 | 78.9/76.5 | 76.2/76.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 21.6/19.5 | 25.7/24.9 | 38.2/36.8 | 39/38 | 37.1/36.5 |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, % | 47.2/47.2 | 13.3/12.9 | 11/10 | 19.4/17.9 | -/- |

| New P2Y12 inhibitors(%; short/12 months DAPT) | 58.9/59.5 | 100/52 | 23.1/22.4 | 39.8/37.1 | 100/100 |

| Mean stent length, mm | 25.5 | 24.8 | 37.9 | 30.4 | 39.9 |

| Stent type | SES with Luminal CD34+Antibody Coating | Biolimus A9-eluting stent | CoCr-EES; platinum-chromium EES or SES with biodegradable polymer | CoCr-EES | Locally approved DES |

ACS, acute coronary sindrome; CoCr-EES, cobalt chromium everolimus-eluting stent; DAPT, discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy; DES, drug-eluting stent; SES, sirolimus-eluting stent.

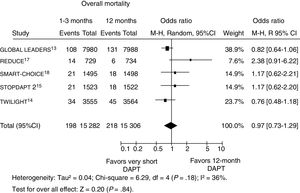

Data on mortality were available in 30 552 patients (99.8% of the total population). A total of 416 patients (1.4%) had died at follow-up, with no significant difference in mortality with shorter vs longer DAPT duration (1.3% [198/1 282] vs 2% [218/15 306], OR, 0.97; 95%CI, 0.73-1.29; P=.84; Phet=.18, figure 2). Similar results were observed when the analysis was restricted to trials randomizing event-free patients at the time of DAPT discontinuation (OR, 0.94; 95%CI, 0.68-1.29, P=.70; Phet=.40). On meta-regression analysis, the impact of DAPT duration on outcomes was not influenced by the rate of patients with acute presentation (r=0.01, 95%CI,−0.008 to 0.02, P=.26). For the assessment of publication bias, symmetric distribution of the mean effect size was observed by visual inspection of the funnel plot generated for the risk of mortality.

Effect of shorter vs longer dual antiplatelet therapy duration on mortality with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The size of the data markers (squares) is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of each trial. 95%CI, confidence interval; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; R, random.

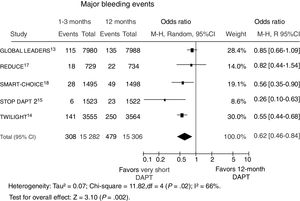

Data on major bleeding events were available in 30 552 patients (99.8%). The BARC (2-5) definition was used in 3 trials,13,17,18 while 1 randomized clinical trial used the BARC (3-5) and another15 the TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) definition. A major bleeding event was documented in 787 patients (2.6%).

As displayed in figure 3, shorter DAPT duration significantly reduced the rate of major bleeding events (2%, [308/15 282] vs 3.1% [479/15 306]), OR, 0.62; 95%CI, 0.46-0.84; P=.002; Phet=.02). The reduction in bleeding events was even more significant in trials randomizing event-free patients at the time of DAPT discontinuation (OR, 0.52; 95%CI, 0.40-0.68, P <.0001; Phet=.27). On meta-regression analysis, the increased risk of hemorrhagic events with very short DAPT was not influenced by the rate of acute patients (r=0.007, 95%CI,−0.01 to 0.026, P=.48). For the assessment of publication bias, symmetric distribution of the mean effect size was observed by visual inspection of the funnel plot generated for the risk of major bleeding events.

Effect of shorter vs longer dual antiplatelet therapy duration on major bleedings with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The size of the data markers (squares) is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of each trial. 95%CI, confidence interval; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; R, random.

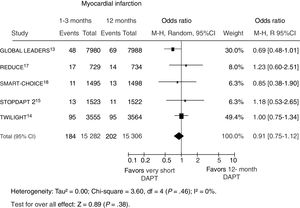

Data on recurrent myocardial infarction were available in 3552 patients (99.8%), of whom 386 (1.3%) experienced an event. No difference in the risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction was observed between a shorter vs longer DAPT strategy (figure 4). On meta-regression analysis, the impact of DAPT duration on myocardial infarction was not influenced by the rate of acute patients (r=0.009, 95%CI,−0.005 to 0.022; P=.21).

Effect of shorter vs longer dual antiplatelet therapy duration on myocardial infarction with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The size of the data markers (squares) is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of each trial. 95%CI, confidence interval; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; R, random.

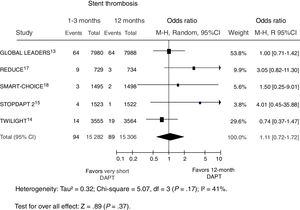

Data on definite/probable stent thrombosis were available in 14 620 patients (44.7%); 1 study13 evaluated only definite stent thrombosis and, furthermore, data were not available at 12 months. A total of 55 patients (0.4%) experienced such an event, with comparable rates in patients receiving shorter vs longer DAPT duration (figure 5). On meta-regression analysis, the risk of stent thrombosis with a shorter DAPT was not influenced by the rate of acute patients (r=0.006, 95%CI,−0.004 to 0.005, P=.81).

Effect of shorter vs longer dual antiplatelet therapy duration on stent thrombosis (definite/probable) with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The size of the data markers (squares) is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of each trial. 95%CI, confidence interval; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; R, random.

The present meta-analysis is the first study to address the prognostic impact of very short (1-3 months) DAPT duration vs the traditional 12-month duration in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary revascularization with modern DES.

In recent years, the technological development of DES has led to a progressive reduction in thrombotic complications, thereby allowing the possibility of a shorter DAPT regimen after PCI, although the modest number and heterogeneity of randomized trials prevent a change in the recommendation of a 12-month DAPT regimen, which is still based on the results of the outdated CURE trial.19,30–33

Therefore, the role of DAPT has recently been reconsidered, progressively shifting from a “protective” antithrombotic treatment for the implanted stent to a preventive strategy for the patient in order to lower the occurrence of recurrent ischemic events. Thus, greater attention has been focused on the evaluation of patient risk profiles, often requiring that a balance be found between thrombotic and bleeding complications, especially as a result of the increased complexity and more advanced age of the population currently undergoing PCI.34,35 Indeed, several studies and registries36–39 have linked anemia and hemorrhagic complications with earlier DAPT discontinuation, leading to an increased risk of ischemic events and impaired survival.

Current guidelines on myocardial revascularization recommend a 6-month DAPT duration as the optimal compromise between thrombosis and bleeding events,8 although they leave a margin for more “individualized” DAPT strategies, either shorter, in the case of high-bleeding risk with low thrombotic profile, or longer, in patients with more advanced coronary disease or acute presentation.

Nevertheless, recent randomized clinical trials have demonstrated the noninferiority of 6-month DAPT compared with the traditional 12 months even in acute coronary syndrome, potentially further expanding the indications for early DAPT discontinuation. In particular, the REDUCE trial,17 specifically dedicated to acute coronary syndrome patients, documented at 2 years of follow-up, the noninferiority of a 3-month DAPT vs 1 year in a total of 1496 patients treated with a new generation DES (COMBO), of whom almost 50% had ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and almost 60% were receiving the more potent oral P2Y12I inhibitors.

The introduction of oral antithrombotic drugs such as ticagrelor and prasugrel has offered new options for the pharmacological management of patients undergoing PCI.40,41 However, the greatest prognostic advantages with these drugs have been demonstrated in association with aspirin. In the context of acute coronary syndrome, recent studies13,14 have suggested that ticagrelor, as a single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT), can also be considered in elective patients, providing the benefit of a more potent antiplatelet drug in the early phases after stent implantation, without exposing the patient to a prolonged risk of hemorrhagic complications.

The GLOBAL LEADERS trial13 compared 1-month DAPT followed by 23-month ticagrelor vs standard 12-month DAPT in 15 968 patients, showing that ticagrelor alone was comparable to standard DAPT for the primary endpoint of mortality and myocardial infarction.

The subsequent TWILIGHT trial14 included patients undergoing PCI who were at high risk of ischemic or hemorrhagic complications. After 3 months, SAPT with ticagrelor was associated with a significant reduction in the primary safety endpoint compared with 12-month DAPT (3.6% vs 7.6%, P <.01), with no difference in the secondary ischemic endpoint (4.3% vs 4.5%).

Several options are now available for DAPT among patients undergoing PCI, including various combinations and durations, although supported by randomized trials performed with dedicated DES and in selected subsets of patients. However, the heterogeneity of the enrolled population and DAPT strategy have so far prevented the generalisability of our results and the inclusion of these findings in routine clinical practice.

The present meta-analysis aimed to assess whether the clinical benefits of very short DAPT among patients undergoing PCI with new DES can be assimilated to a “class” effect for all the different DAPT strategies globally or should rather be considered only in special settings. We demonstrated that the early discontinuation of the second antiplatelet agent within the first 1 to 3 months after randomization is associated with a significant reduction in hemorragic complications without increasing the risk of thrombotic events and has a null effect on mortality.

The greatest benefits on the occurrence of bleeding events were observed in studies enrolling patients at the time of DAPT discontinuation and which therefore evaluated only the benefits of SAPT while excluding those patients experiencing an event during the first phase of mandatory DAPT. However, a previous subanalysis of the PLATO trial40 showed that most noncoronary artery bypass graft-related bleeding events occurred within the first 30 days after randomization, thereby further indicating the importance of correct stratification of patient risk profile, accounting for both clinical and angiographic features, even before PCI, in order to assign the patients to the best strategy for coronary revascularization and antithrombotic therapy.

Although very short DAPT appears safe and effective in most the patients treated with modern DES, a more individualized approach is still warranted and future randomized trials are required to shed light on the criteria to be applied for DAPT optimization.

LimitationsThis meta-analysis has some limitations. The most important relates to the synthesis of data from trials including patients with both chronic and acute coronary syndrome and with different ischemic and bleeding risk profiles. However, no significant heterogeneity was found in our primary efficacy and safety endpoints and, moreover, such a broad spectrum of patients could also represent a strength of our meta-analysis, revealing the feasibility of very short DAPT in a large-scale population, as in real life.

Moreover, the definition of the primary composite endpoint differed among the distinct studies (including in certain trials stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding events) and therefore we preferred to evaluate mortality as our primary endpoint and the individual components of ischemic risk (myocardial infarction). However, based on the negative findings of our analysis and the similar conclusions of previous studies,42–44 we do not expect the findings to differ if the overall rate of MACE were evaluated.

The use of different stents is another important limitation. Stents were restricted to newer DES technologies, leading to a faster re-endothelization and lower thrombotic risk.42 Furthermore, we included different antiplatelet strategies, since aspirin was discontinued in most trials, while long-term treatment consisted of either ticagrelor or clopidogrel. Equally, we were unable to evaluate studies maintaining DAPT for 1 or 3 months separately, due to the small number of included trials. Nevertheless, our findings are not dissimilar to the previous conclusions of trials and meta-analyses performed with 6- vs 12-month DAPT,43 although no study has so far compared a strategy of 1 to 3 months vs 6 months. In addition, 30-day of DAPT has proven sufficient to prevent thrombotic events with most modern DES.44

Finally, the delayed randomization strategy used in some trials, restricting inclusion to event-free patients at the end of the minimum planned DAPT duration, may have excluded high-risk patients who might have obtained greater benefits from a shorter or more prolonged DAPT, such as those with advanced age, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction presentation, complex coronary anatomy, diabetes, renal failure, or the need for oral anticoagulation.

ConclusionsBased on the current meta-analysis, DAPT discontinuation after a short (1-3 months) period of DAPT is associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding events compared with the standard 12-month therapy, with no increase in major ischemic events and comparable survival. Therefore, very short DAPT can be safely considered among patients undergoing PCI with modern DES, especially if at high-risk for bleeding complications. Future randomized trials are needed to better define the best long-term antiplatelet strategy.

- -

Current guidelines on myocardial revascularization recommend 6-month DAPT as the optimal compromise between thrombosis and bleeding events.

- -

Recent randomized trials have shown the feasibility of extremely short (< 6 months) DAPT strategies and early discontinuation of aspirin.

- -

We performed a meta-analysis of 5 randomized clinical trials and more than 30 000 patients undergoing PCI with modern DES.

- -

We demonstrate that the early discontinuation of the second antiplatelet agent within the first 1 to 3 months after randomization is associated with a significant reduction in hemorrhagic complications without increasing the risk of thrombotic events and no effect on mortality.

- -

Future randomized trials are required to shed light on the criteria to be applied for the optimization of DAPT.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2020.03.009