Most cases of aortitis are noninfectious and their clinical presentation varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic aortic aneurysm to acute chest pain or heart failure.1 Some patients with aortitis may simulate an acute aortic syndrome (AAS) at presentation.2 Because treatment strategies for aortitis and AAS diverge widely, an accurate diagnosis is of the utmost importance.

We report 2 cases of IgG-4 aortitis simulating an intramural aortic hematoma (IAH). In addition, we provide a detailed literature-based review of patients with aortitis mimicking an IAH. The main diagnostic clues to differentiate these 2 types of aortic entities are presented in table 1.

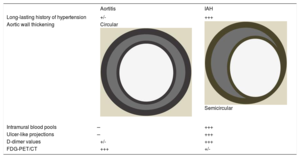

Key differences in diagnosis between aortitis and IAH

| Aortitis | IAH | |

|---|---|---|

| Long-lasting history of hypertension | +/- | +++ |

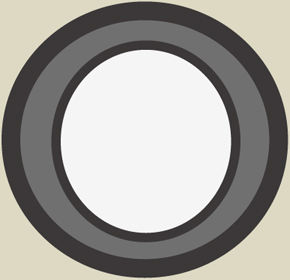

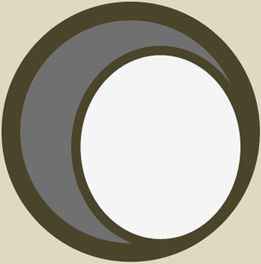

| Aortic wall thickening | Circular | Semicircular |

| Intramural blood pools | ̶ | +++ |

| Ulcer-like projections | ̶ | +++ |

| D-dimer values | +/- | +++ |

| FDG-PET/CT | +++ | +/- |

CT, computed tomography; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; IAH, intramural aortic hematoma; PET, positron emission tomography.

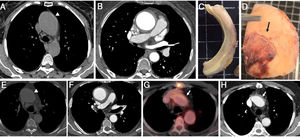

Patient 1. A 76-year-old woman with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm (45mm) and aortic regurgitation (AR) presented to the emergency department with acute and severe chest pain. Blood pressure was 170/80 mmHg and D-dimer value was 1130 ng/mL. Urgent computed tomography (CT) suggested an IAH in the aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch. An ascending aortic aneurysm (50mm) with a circular aortic wall thickening (8mm) was documented (figure 1A,B). The patient underwent urgent surgery with replacement of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and arch. At surgery, a marked thickening of the aortic wall without signs of intramural hemorrhage was documented (figure 1C). In addition, periaortic inflammation was evident (figure 1D). Pathologic examination of aortic tissue showed the presence of a large IgG-4 lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. A high-dose corticosteroid regimen was initiated and subsequently tapered with excellent clinical response and follow-up.

Series of anatomic pieces and imaging test corresponding to 2 patients with aortitis simulating an aortic intramural hematoma (A-H). A-E: noncontrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) slice showing hyperattenuated thickened aortic wall involving the ascending aorta (arrowhead). Hypointense circular aortic wall thickening affecting the ascending aorta (B,F) and intimal calcium displacement (F). Macroscopical images of the excised ascending aorta showing a marked aortic wall thickening without intramural hemorrhage (C), and the presence of significant periaortitis (arrow) (D). Postsurgical CT and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT slices in which the remaining thick aortic arch wall segment had an increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (arrow) (G,H).

Patient 2. A 69-year-old man with no cardiovascular risk factors presented to the emergency room with syncope. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve with moderate AR. A CT scan showed an ascending aortic aneurysm (54 mm) with a circular aortic wall thickening (10 mm) involving the ascending aorta, aortic arch (figure 1E,F), brachiocephalic trunk, and left carotid artery. D-dimer levels were 356 ng/mL. The patient was sent to surgery with the diagnostic suspicion of IAH. At surgery, there was no hematoma within the thick ascending aortic wall. Immunohistochemical analysis gave the diagnosis of IgG-4 aortitis. A postoperative follow-up positron emission tomography (PET)/CT showed a remaining thick aortic arch wall segment with intense fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake (figure 1G,H). The patient received a high-dose corticosteroid regimen with good clinical and PET/CT follow-up response.

As to specific cases of aortitis mimicking an IAH, we performed a review of the literature to collect data from all cases of aortitis simulating an IAH. Finally, we found 10 cases reported in the literature in addition to our 2 patients.

This series collects data from patients with aortitis who were incorrectly diagnosed with an IAH. Aortitis is an inflammatory disorder involving the aortic wall.1 Diffuse arterial wall thickening (> 2mm) and homogeneous wall enhancement are typical features of aortitis on contrast-enhanced CT.3 In addition, PET/CT may depict the inflammatory process and monitor therapeutic response during follow-up.4 Glucocorticoid therapy is the mainstay therapy in noninfectious aortitis.1,2,4

IAH is an acute aortic entity that belongs to what is widely known as AAS .5 Diagnosis is usually made by CT, transesophageal echocardiography, or magnetic resonance. The aortic wall does not generally show enhancement with contrast administration on CT. Most cases of type A IAH are treated surgically.5

This case series of patients with aortitis mimicking a type A IAH shows several interesting features that should help in the differential diagnosis of these 2 entities. In all patients, the aortic wall thickening was circular instead of semicircular or crescentic, as is frequently the case of IAH.5 None of the cases showed intramural blood pools or ulcer-like projections, so characteristic of IAH.2,4 However, some of the typical imaging signs of IAH were also present in patients with aortitis, such as central displacement of intimal calcification, hyperintensity in noncontrast CT images, and absence of enhancement with contrast administration.2,4 Regarding the aortic valve, it is possible to have significant AR in both conditions. In aortitis, AR may result from aortic valve inflammation (7 cases in this series).

Laboratory parameters are not very specific; in aortitis, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are usually elevated (6 patients of this series),2–4 but they can occasionally be normal. Acute phase reactants may also be increased in IAH. Thus, these parameters are not definitive. A laboratory parameter that could ultimately be useful in the emergency department is the D-dimer. In patients with AIH, D-dimers are usually high. D-dimer levels were slightly high in 1 of our patients and normal in the other. Unfortunately, they were not measured in the other patients.

PET/CT imaging may play a key role in establishing the diagnosis of aortitis and assessing the extent of the disease to other aortic segments. In addition, it is very helpful in the follow-up of these patients to monitor the therapeutic response.4 In IAH FDG uptake is null or low intensity.

Interestingly, most cases of aortitis in this series (8 patients) were IgG-4 aortitis.2 Hypothetically, this type of aortitis may be more likely to simulate an IAH. IgG4-related disease may also present as other cardiovascular conditions, such as pericarditis or intracardiac pseudotumors. Although heart failure as a consequence of valvular dysfunction is usually the form of presentation in cases of intracardiac mass, cardiac arrest and conduction disturbances have also been described as a result of IgG4-related disease.6 Aortitis is no longer a rare condition, and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with AAS, particularly IAH.

In summary, in patients presenting to the emergency room with chest pain and a thickened ascending aortic wall, the following features should give rise to suspicion of aortitis: absence of a long-lasting history of hypertension, circular aortic wall thickening with absent intramural blood pools or ulcer-like projections, and normal D-dimer values (table 1).