The number of patients with Chagas disease in Spain has increased significantly. Chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction have been considered among the physiopathological mechanisms of Chagas heart disease. However, there have been conflicting data from clinical studies. Our purpose was to assess endothelial function and systemic levels of nitric oxide and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in patients with the indeterminate form and with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy living in a nonendemic area.

MethodsFlow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation were assessed with high-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery in 98 subjects (32 with the indeterminate form, 22 with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy and 44 controls). Nitric oxide and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were measured in peripheral venous blood.

ResultsMean age was 37.6±10.2 years and 60% were female. Nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation was significantly reduced in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy compared to controls (median 16.8% vs 22.5%; P=.03). No significant differences were observed in flow-mediated vasodilatation and nitric oxide levels, although a trend towards lower flow-mediated vasodilatation after correction by baseline brachial artery diameter was observed in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. Levels of C-reactive protein were significantly higher in patients with the indeterminate form and with Chagas cardiomyopathy compared with controls (P<.05).

ConclusionsReduced nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation suggesting dysfunction of vascular smooth muscle cells was found in patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy living in a nonendemic area. Higher C-reactive protein levels were observed in the indeterminate form and early stages of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy, which could be related to the inflammatory response to the infection or early cardiovascular involvement.

Keywords

Chagas disease remains a common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy in Latin America. Moreover, as a consequence of migration Chagas disease has become a public health problem in areas where the disease is not endemic, as in Spain where recent studies estimate a prevalence between 48 000 and 68 000 Trypanosoma cruzi-infected persons.1 Physiopathology of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCC) remains poorly understood. Chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction have been considered among the physiopathological mechanisms of the disease, supported by experimental data.2 However, there are conflicting results from clinical studies on endothelial function and systemic nitric oxide (NO) levels3, 4, 5, 6, 7 in Chagas disease. Most studies assessing C-reactive protein (CRP) have shown increased levels in children during the acute phase of the disease8 and in patients with very severe stages of CCC, but not in the indeterminate form or early stages of CCC.9, 10 In addition, there are no data regarding endothelial function or high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) levels in Chagas disease patients living in nonendemic areas and therefore free of reinfection. Our aim was to assess endothelial function and systemic NO and hsCRP levels in a cohort of patients with the indeterminate form of CCC living in a nonendemic area.

METHODS Study PopulationA cross-sectional study was performed in a cohort of consecutive adult subjects evaluated in our institution from January 2008 to June 2009. Diagnosis of Chagas disease was based on microbiologic confirmation, as previously described11. Subjects from endemic areas and negative T. cruzi serology were included as controls. Exclusion criteria were heart disease of another etiology, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, systemic or immunological diseases, other active infections, or previous antiparasitic treatment. The Ethics Committee of our institution approved the research protocol and written informed consent was obtained from participants.

According to structured medical interviews, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and conventional 2D-echocardiography, subjects were classified into 3 groups: Control group (subjects with negative serology for Chagas disease); Indeterminate group (those with positive serology of Chagas disease, normal electrocardiogram and normal left ventricular [LV] dimensions and LV global and regional systolic function); and CCC group (patients with positive T. cruzi serology and any of the typical electrocardiographic abnormalities of Chagas disease11 and/or any regional wall motion abnormality, LV end-diastolic diameter >55mm or LV ejection fraction [LVEF]<50%). LV dimensions were determined according to American Society of Echocardiography recommendations12 and LVEF was calculated using the modified Simpson biplane method.

Endothelial Function AssessmentEndothelial function was studied using high-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery as previously described.13, 14 Briefly, a longitudinal section of the right brachial artery above the antecubital fossa was scanned with a vascular transducer mounted in a mechanical support system to achieve a steady image throughout the study. Baseline images were recorded at rest. Flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilatation (FMD) was assessed by the change in the brachial artery diameter in response to increased flow (reactive hyperemia) achieved by the rapid release of a pneumatic cuff around the forearm inflated at 300mmHg for 4.5min. Patients rested 10 to 15min to allow brachial artery recovery, and then endothelium-independent nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation (NMD) was assessed 5min after administering a sublingual dose of nitroglycerin (0.4mg). One blinded, experienced observer analyzed all images. Arterial diameter was measured from 2D-ultrasound images at the peak of the R wave of the electrocardiogram using dedicated software. The FMD and NMD were expressed as the percentage of change in brachial artery diameter from baseline. Additionally, percentages were corrected by baseline brachial artery diameter, as this influences FMD.

Biochemical MeasurementsMeasurements of NO and hsCRP levels were made in peripheral venous blood and quantified using commercially available kits. Serum concentration of NO was determined with a chemiluminescence detector (Sievers Instruments, Inc., Boulder, Colorado, United States). Plasma levels of hs-CRP were measured by a commercially available immunoturbidimetric method (ADVIA 2400 Chemistry CardioPhaseTM, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Tarrytown, New York, United States).

Statistical AnalysisSample size estimation was performed based on previous data of our group.13 The sample size required to detect a difference of 2.5% in FMD between Chagas disease patients and controls with a significance level of 0.05 and power of 0.80, assuming a overall standard deviation of 3%, was 23 patients in each group, therefore 69 patients in total. Continuous baseline variables were expressed as median [interquartile range] and categorical variables as total number (percentages). Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the Wilcoxon test. Correlations were assessed using Pearson coefficient. χ2 test or Fisher's test was applied for categorical variables as appropriate. Marginally adjusted means for endothelial function parameters by age were calculated using multivariable regression models. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTSNinety-eight consecutive subjects were included: 44 in the Control group, 32 in the Indeterminate group, and 22 in the CCC group. Categorization as CCC was based on isolated typical-electrocardiographic findings in 14 patients, segmental motion abnormalities in 1 patient, and LVEF <50% in 7 patients. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Control individuals were younger than patients with Chagas disease. CCC patients showed larger LV volumes and a reduced LVEF compared to controls.

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics and Conventional Echocardiographic Data of the Study Population.

| Control (N=44) | Indeterminate (N=32) | CCC (N=22) | P1-2 | P1-3 | |

| Age (years) | 34 [11.5] | 36.8 [14.6] | 42.7 [13] | .034 | .002 |

| Female | 26 (59) | 21 (66) | 12 (55) | .663 | .725 |

| Heart rate (bmp) | 60 [8.8] | 65 [10] | 60 [15] | .204 | .602 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 110 [15] | 114 [24.2] | 115 [20.5] | .090 | .080 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 70 [14.8] | 70 [18] | 70 [20.8] | .266 | .217 |

| Smokers | 6 (14) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (13.6) | .300 | 1.000 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 2 (4.7) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (13.6) | 1.000 | 1.198 |

| NYHA FC II | 0 | 0 | 5 (22.7) | NA | .003 |

| LVEDV (ml/m2) | 59.5 [13.2] | 56.2 [14.3] | 73.4 [24.3] | .066 | <.001 |

| LVESV (ml/m2) | 23.6 [7.4] | 21.7 [6.6] | 30.9 [23.9] | .137 | <.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 64.5 [5] | 65 [4.8] | 57.5 [22.3] | .362 | .005 |

BP, blood pressure; CCC, chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume indexed to body surface area; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume indexed to body surface area; NA, nonapplicable; NYHA FC, New York Heart Association functional class. P1-2, P value for the comparison between Indeterminate and Control group; P1-3, P value for the comparison between CCC and Control groups.

Continuous variables are expressed as median [interquartile range]; categorical variables are expressed as no. (%).

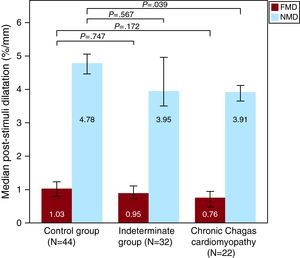

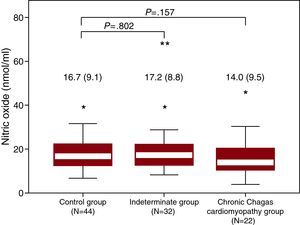

NMD was significantly reduced in the CCC group compared to controls (Table 2). After adjusting for age (21.9±9.1 vs 17.5±6.3, P=.026) or correcting by baseline brachial artery diameter (Figure 1), the difference remained statistically significant. Patients in the Indeterminate group showed high NMD variability, with intermediate values compared to Control and CCC groups. No statistical differences in FMD and systemic levels of NO were found between groups (Figure 2), although a trend towards lower FMD after correction by baseline brachial artery diameter in CCC patients as compared with controls was observed (Figure 1).

Table 2. Endothelial Function Assessed by Brachial Artery Ultrasound by Groups.

| Control (N=44) | Indeterminate (N=32) | CCC (N=22) | P1-2 | P1-3 | |

| Baseline artery diameter | 3.5 [0.9] | 3.6 [0.9] | 4 [1.1] | .663 | .135 |

| Reactive hyperemia | 6.6 [2.2] | 6.4 [3.2] | 6.1 [2.4] | .863 | .369 |

| FMD (%) | 4.0 [4.8] | 3.4 [3.2] | 3.5 [4.1] | .897 | .262 |

| FMD normalized (%/mm) | 1.03 [1.66] | 0.95 [1.2] | 0.76 [1.08] | .747 | .172 |

| NMD (%) | 22.3 [8.6] | 17.8 [11.3] | 16.8 [8.9] | .291 | .032 |

| NMD normalized (%/mm) | 4.78 [2.7] | 3.95 [3.75] | 3.91 [1.86] | .567 | .039 |

CCC, chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy; FMD, flow mediated endothelim-dependent vasodilatation; NMD, nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation; P1-2, P value for the comparison between Indeterminate and Control group; P1-3, P value for the comparison between CCC and Control groups.

Variables are expressed as median [interquartile range].

Figure 1. Endothelium-dependent flow-mediated and nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation by groups. Poststimuli dilatation is expressed as percentage of change in brachial artery diameter corrected by baseline artery diameter. Bars show median and interquartile range. FMD, flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilatation; NMD, nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation.

Figure 2. Systemic levels of nitric oxide by groups. Values are expressed as median (interquartile range).* Symbol shows minor outlier (observation 1.5 × interquartile range outside the central box) and ** shows major outlier (observation 3.0 × interquartile range outside the central box).

NO levels were higher in patients with the lowest FMD (first quartile, including vasoconstrictor response to minimal dilatation) compared to patients with the largest FMD (fourth quartile), median of 18.3 vs 12.7 nmol/ml; P=.026. No association was observed between NO levels and NMD.

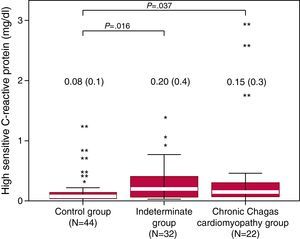

Serum Levels of High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein LevelsSystemic levels of hsCRP were higher in patients with the indeterminate form compared with controls (median 0.20 vs 0.08mg/dl; P=.016) and in CCC patients compared with controls (median 0.15 vs 0.08; P=.037). Distribution of hsCRP concentrations in each group is illustrated in Figure 3. Serum hsCRP correlated inversely with LVEF (r=-0.34; P=.001) and positively with the deceleration time of the mitral E wave (r=0.22; P=.036), total leucocytes (r=0.51, P<.001) and interleukin-6 (r=0.30, P=.08). No association was found between hsCRP levels and FMD or NMD.

Figure 3. Plasmatic levels of high sensitivity C-reactive protein by groups. Values are expressed as median (interquartile range).* For minor outliers and ** for major outliers.

DISCUSSIONNMD was reduced in CCC patients compared to controls. No statistically significant differences between groups were observed in FMD and systemic levels of NO, although a trend towards lower FMD after correction by baseline brachial artery diameter was observed in the CCC group. Serum levels of hsCRP were significantly higher in the Indeterminate and CCC groups compared with controls.

Nitroglycerin activity depends on its conversion to NO inside the smooth muscle cells, producing the activation of guanylate clyclase, accumulation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, and subsequent vasodilatation. Therefore, our results suggest that structural or functional changes in vascular smooth muscle, such as occurs in gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells in the gastrointestinal form, may exist in CCC. These findings are in concordance with recent experimental studies. Gene-expression microarray analysis in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells infected by T. cruzi15 has revealed up-regulated expression of thrombospondin-1, which antagonizes the NO-guanylate cyclase pathway and thereby negatively regulates vascular tone. In other experimental studies, T. cruzi infection of smooth muscle cells resulted in sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 216 and other enzymes involved in vascular injury and smooth cell proliferation.17 Should functional changes exist in vascular smooth cells, the finding of significant differences in NMD and not in FMD could be related to the much lower magnitude of FMD, which reduces statistical power. Alternatively, as reactive hyperemia activates 2 pathways (NO-guanylate cyclase and prostacyclin), a compensatory increase of the prostacyclin pathway could mask differences in FMD.18 Indeed, increased levels of cyclooxygenase metabolites have been found in experimental T. cruzi infection.19 On the other hand, although inducible NO synthase can be increased in Chagas disease, particularly in acute infection, this enzyme does not seem to participate directly in FMD.20 The absence of statistically significant differences in NMD between the Indeterminate and Control groups might be partially explained by the high variability in NMD values in the Indeterminate group. This finding was predictable, as the Indeterminate group was expected to be the most heterogeneous, potentially including patients with positive serology but absence of cardiovascular involvement (theoretically with normal NMD) and patients with incipient cardiovascular damage (theoretically with NMD ranging from normality to that found in the CCC group).

Endothelial function in Chagas disease has been evaluated, with divergent results, in previous studies, all of them with smaller sample sizes. Guzman et al. found both endothelial-dependent and NMD dysfunction in 22 asymptomatic seropositive individuals.4 Conversely, Torres et al. observed reduced vasodilatation after acetylcholine infusion but preserved response with adenosine in 9 CCC patients,7 and Consolim-Colombo et al. compared 9 CCC patients and 10 healthy subjects and found no differences after acetylcholine or nitroprusside infusion.3 Different methodologies used to assess endothelial function, and insufficient statistical power in some cases, could partially explain the discrepancies of previous studies. There is also controversy regarding systemic NO levels in Chagas disease. Pissetti et al. found lower NO levels in Chagas disease patients compared to controls6 whereas Perez-Fuentes et al. found them to be significantly increased.5 It is well documented that T. cruzi infection triggers substantial production of NO in the acute phase.21 However, an experimental model with dogs inoculated with parasites showed that serum levels of NO were higher at days 14 and 28 but not at day 35.22 Distinctive characteristics of our population, particularly the absence of reinfections and the inclusion of CCC patients in early stages of the disease (mostly defined by electrocardiographic findings), could explain the lack of differences in NO levels in our study.

Serum levels of CRP have been found significantly higher in children in the acute phase of the disease and in advanced stages of CCC. Although no significant differences have been observed in early phases, a trend towards progressive increase in CRP and other inflammatory markers across severity of Chagas heart disease has been consistently reported9, 10 In our study using a hsCRP assay, levels in the Indeterminate and CCC groups were higher as compared to controls. As illustrated in Figure 3, distribution of CRP in all groups was positively skewed, particularly in the Indeterminate and CCC groups. Similar distribution was observed by Saravia et al. using hsCRP.23 Of note, in the indeterminate form extreme values could be of more relevance than median values, as only about one third of patients will develop cardiac manifestations CRP, a nonspecific marker of inflammation that increases in the context of infections and cardiovascular diseases, has been associated with increased risk for cardiovascular events. Moreover, CRP may play a direct role in promoting vascular inflammation, vessel damage and clinical cardiovascular disease events, although this remains controversial.24, 25 In Chagas disease, it is yet to be determined whether greater CRP levels are related to the inflammatory response to the infection, early cardiovascular involvement, or both. In our study, CRP correlated mildly with LVEF and mitral E-wave deceleration time and moderately with total leucocytes and interleukin-6 levels.11 Longitudinal studies are needed to determine if higher levels of CRP in the indeterminate and early phases of CCC are associated with progression of cardiovascular damage.

Our results may have some clinical implications. Although approximately one third of T. cruzi infected patients will develop CCC, recognizing those patients is currently not possible. Additionally, there are no early markers of cure or progression of the disease after antiparasitic treatment. Our results suggest that NMD assessment and CRP levels measurement could be useful for early detection of cardiovascular involvement in patients in the indeterminate form of Chagas disease, in which antiparasitic and heart failure medications could be more beneficial and closer follow-up should be considered. Also, NMD and CRP assessment could potentially serve to monitor the response to pharmacological therapies. Larger longitudinal studies are required to evaluate the clinical utility of these findings.

Some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. By using ultrasound of the brachial artery, we can indirectly measure the function of the vascular smooth muscle but we cannot distinguish between structural (ie, fibrosis) and functional damage. In addition, no prostacyclin pathway-derived metabolites were measured. The cross-sectional design of the study does not allow inferences about causation. Although important potential confounders were avoided by the exclusion criteria, unmeasured confounders might have existed.

CONCLUSIONReduced NMD suggesting dysfunction of vascular smooth muscle cells was found in patients in early phases of CCC living in a nonendemic area. Patients in early phases of CCC and in the indeterminate form had higher levels of hsCRP. This finding could possibly be related to the inflammatory response to the infection or early cardiovascular involvement.

FUNDINGThe study was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain (PI 070773) and Red HERACLES (RD06/0009/0008).

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

Received 8 March 2011

Accepted 14 May 2011

Corresponding author: Fundación Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III, Melchor Fernández Almagro 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain. gsanz@cnic.es