Diabetes remains a leading cause of cardiovascular disease and other disabling and life-threatening complications. Effective management strategies are therefore of obvious importance. Recent clinical trials in older patients have failed to show a benefit from intensive glucose-lowering therapy on cardiovascular disease outcomes.1,2 The American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes have emphasized the need for individualized glycemic targets according to age, coexisting conditions, and time since diagnosis.3 The recommendations range from a stringent glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) target (<6%-6.5%) in selected patients (without overt cardiovascular disease, shorter duration of diabetes, and long life expectancy) to less stringent HbA1c goals (<7.5%-8%) in patients with a history of severe hypoglycemia, limited life-expectancy, and severe complications.3

This article is the first to report the achievement of individualized glycemic targets among diabetic patients in Spain. Additionally, we compare our results with recently reported results in the United States diabetic population.4

Spanish data were taken from the ENRICA study, whose methods have been reported elsewhere.5,6 In brief, this was a cross-sectional study conducted from 2008 through 2010 in 12 948 individuals representative of the population in Spain aged ≥18 years. To determine the achievement of glycemic targets, we limited the analyses to the 661 patients who were aware of their condition. Diabetes was defined as a 12-h fasting serum glucose ≥126mg/dL or HbA1c≥6.5%, or treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs or insulin.5 We could not distinguish between type-1 and type-2 diabetes, but it is likely that, as in many other developed countries, most patients had type-2 diabetes. Diagnosed diabetic patients in the United States were 1444 adults, who reported having received a diagnosis of diabetes from a health professional, from the NHANES study conducted between 2007 and 2010.4 In both studies, similar data collection methods and similar sampling techniques were used to ensure the representativeness of the population samples. Diabetes complications were defined as self-reported diagnosed cardiovascular disease, or retinopathy, or measured albumin:creatinine ratio ≥30mg/dL. Spanish data did not include retinopathy, because this information was not available in the ENRICA study. All of the United States data were taken from Ali et al4, as they appear in the publication. The chi-square test was used to compare the percentage of the individualized glycemic-target between the 2 population samples. Statistical significance was set at 2-sided P<.05. The analyses were performed with EPIDAT v.3.1 statistical software.

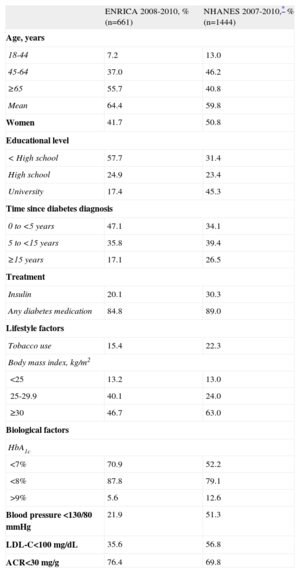

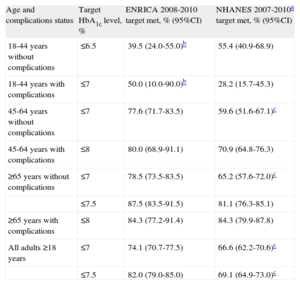

Spanish diabetic patients were more frequently men (58.3%) with a low educational level (57.7% had not attended high school); almost half of them had been diagnosed with diabetes less than 5 years previously, and only a few (20%) received insulin therapy; while these patient had a low frequency of kidney damage (23.6%) and a reasonably good glycemic control (70.9%), only one-fifth and one-third achieved blood pressure and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol goals, respectively (Table 1). When individualizing glycemic targets (Table 2), only individuals over 45 years showed control rates similar to that for standard criteria (HbA1c<7%). In younger individuals, the results were not consistent due to low sample sizes.

Characteristics of Diagnosed Diabetic Patients in Spain and the United States

| ENRICA 2008-2010, % (n=661) | NHANES 2007-2010,* % (n=1444) | |

| Age, years | ||

| 18-44 | 7.2 | 13.0 |

| 45-64 | 37.0 | 46.2 |

| ≥65 | 55.7 | 40.8 |

| Mean | 64.4 | 59.8 |

| Women | 41.7 | 50.8 |

| Educational level | ||

| < High school | 57.7 | 31.4 |

| High school | 24.9 | 23.4 |

| University | 17.4 | 45.3 |

| Time since diabetes diagnosis | ||

| 0 to <5 years | 47.1 | 34.1 |

| 5 to <15 years | 35.8 | 39.4 |

| ≥15 years | 17.1 | 26.5 |

| Treatment | ||

| Insulin | 20.1 | 30.3 |

| Any diabetes medication | 84.8 | 89.0 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Tobacco use | 15.4 | 22.3 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| <25 | 13.2 | 13.0 |

| 25-29.9 | 40.1 | 24.0 |

| ≥30 | 46.7 | 63.0 |

| Biological factors | ||

| HbA1c | ||

| <7% | 70.9 | 52.2 |

| <8% | 87.8 | 79.1 |

| >9% | 5.6 | 12.6 |

| Blood pressure <130/80 mmHg | 21.9 | 51.3 |

| LDL-C<100 mg/dL | 35.6 | 56.8 |

| ACR<30 mg/g | 76.4 | 69.8 |

ACR, urinary albumin:creatinine ratio; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Achievement of Individualized Glycemic Targets Among Diagnosed Diabetic Patients in Spain and the United States

| Age and complications status | Target HbA1c level, % | ENRICA 2008-2010 target met, % (95%CI) | NHANES 2007-2010a target met, % (95%CI) |

| 18-44 years without complications | ≤6.5 | 39.5 (24.0-55.0)b | 55.4 (40.9-68.9) |

| 18-44 years with complications | ≤7 | 50.0 (10.0-90.0)b | 28.2 (15.7-45.3) |

| 45-64 years without complications | ≤7 | 77.6 (71.7-83.5) | 59.6 (51.6-67.1)c |

| 45-64 years with complications | ≤8 | 80.0 (68.9-91.1) | 70.9 (64.8-76.3) |

| ≥65 years without complications | ≤7 | 78.5 (73.5-83.5) | 65.2 (57.6-72.0)c |

| ≤7.5 | 87.5 (83.5-91.5) | 81.1 (76.3-85.1) | |

| ≥65 years with complications | ≤8 | 84.3 (77.2-91.4) | 84.3 (79.9-87.8) |

| All adults ≥18 years | ≤7 | 74.1 (70.7-77.5) | 66.6 (62.2-70.6)c |

| ≤7.5 | 82.0 (79.0-85.0) | 69.1 (64.9-73.0)c |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin.

Complications were defined as self-reported diagnosed cardiovascular disease (heart attack, coronary heart disease, or stroke) or retinopathy or measured albumin:creatinine ratio ≥30mg/g (Spanish data did not include retinopathy, because such information was not available).

Compared with United States diabetic patients (Table 1), Spanish patients were older (mean age 64.4 vs 59.8 years), were less often smokers (15.4% vs 22.3%), were less frequently obese (46.7% vs 63.0%), and had a shorter duration of diabetes (17.1% vs 26.5% ≥15 years); these findings could be due to the traditionally lower prevalence of obesity in Spain. Although the percentages of Spanish diabetics who achieved targets for blood pressure and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol were smaller than the United States rates (21.9% vs 51.3%; and 35.6% vs 56.8%, respectively), our population showed a lower frequency of kidney damage (23.6% vs 30.2%) and better glycemic control (70.9% vs 52.2%). Both findings may be explained by the above-mentioned shorter time since diagnosis, which could also account for the lower use of insulin among Spanish diabetic patients (20.1% vs 30.3%). However, when we compared individualized glycemic targets (Table 2), the better control in Spain was only evident (P<.05) in patients over 45 years without diabetic complications. Further investigations are warranted to determine whether this finding was due to a shorter evolution of diabetes or simply to the small sample sizes.

In conclusion, glycemic control among Spanish diabetic patients is reasonably good when individualized targets are used. However, this should not lead to complacency since these results could be explained by a shorter duration of diabetes in our diabetic population.

FundingThe ENRICA study is funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Additional funding was obtained from Cátedra UAM de Epidemiología y Control del Riesgo Cardiovascular. The ENRICA study is being run by an independent academic steering committee.