Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (TIC) is a heart disease characterized by ventricular dysfunction and dilatation secondary to sustained tachyarrhythmia that is reversible with heart rate control. It is diagnosed after exclusion of other causes of cardiomyopathy and recovery in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of at least 15% after heart rate control. The ventricular dysfunction generated by TIC is sometimes extremely serious, leading to heart failure, arrhythmias, and sudden death.1 TIC is frequently associated with atrial fibrillation. Because TIC is generally considered a benign and reversible condition, it is probably underdiagnosed. However, recent studies indicate that it may cause persistent subclinical damage.2–4 The true prognosis of the disease is unknown, as well as the mechanisms underlying its reversibility and whether it causes an irreversible subclinical condition.

The present study analyzes the baseline clinical, electrocardiographic, and cardiac imaging characteristics of patients with TIC, their long-term outcomes, and the association of these characteristics with adverse events during follow-up. The study comprises a retrospective analysis of a series of patients diagnosed with TIC and evaluated and followed up in our center between March 2006 and March 2016. Patients with other heart diseases and/or possible triggers were excluded. Clinical treatment was provided according to clinical practice guidelines and at the discretion of the treating physician. LVEF relapses (an LVEF < 50% or a reduction ≥ 15%) during follow-up were analyzed after their complete or partial recovery, as well as their association with prognostic factors. Delayed relapses were those that occurred from the fifth year of follow-up onward. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a chi-square test, the Student t test, and the Mann-Whitney U test; survival analysis was performed using a Cox regression model and Kaplan-Meier estimator. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

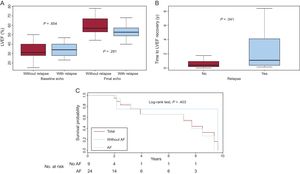

In total, 36 patients (23 men) were evaluated with a mean follow-up of 3.2 ± 2.9 years (Table). The most frequent cause of TIC was atrial fibrillation (72%). In 70% of the patients, their symptoms were not directly attributable to their arrhythmia. Eleven LVEF reductions were detected during follow-up (30% of patients; median time from treatment initiation to relapse, 3.08 [0.32-8.03] years) due to arrhythmic relapse or poor control of the original arrhythmia; of these relapses, 5 were delayed (14%). In patients who had a relapse, there were no significant differences in LVEF at treatment initiation or after ventricular function recovery (Figure A). Nonetheless, these patients did show slower LVEF recovery from disease initiation (0.39 [0.21-0.75] vs 1.13 [0.36-4.10] years; P = .041) (Figure B) and their clinical follow-up was significantly longer (2.1 ± 2.0 vs 5.6 ± 3.1 years; P = .007). In contrast, patients treated with ablation of the triggering arrhythmia were nonsignificantly less likely to have a relapse (P = .076), regardless of the type of arrhythmia ablated. There were no significant differences in the relapse-free survival curves between patients with atrial fibrillation and those with other arrhythmias (Figure C). Nonetheless, Cox regression analysis showed that atrial fibrillation multiplied the relapse risk during follow-up by 2.42, although the difference was again not statistically significant (95% confidence interval, 0.29-20.4; P =.416). Only 1 death occurred, from noncardiovascular causes.

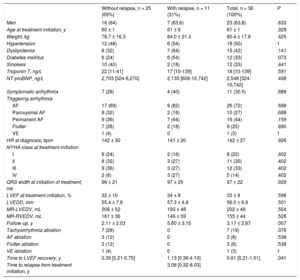

Characteristics of the Study Population

| Without relapse, n = 25 (69%) | With relapse, n = 11 (31%) | Total, n = 36 (100%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 16 (64) | 7 (63.6) | 23 (63.8) | .633 |

| Age at treatment initiation, y | 60 ± 1 | 61 ± 9 | 61 ± 1 | .929 |

| Weight, kg | 78.7 ± 16.3 | 84.0 ± 21.3 | 80.4 ± 17.8 | .425 |

| Hypertension | 12 (48) | 6 (54) | 18 (50) | 1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 8 (32) | 7 (64) | 15 (42) | .141 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (24) | 6 (54) | 12 (33) | .073 |

| Smokers | 10 (40) | 2 (18) | 12 (33) | .441 |

| Troponin T, ng/L | 22 [11-41] | 17 [10-139] | 18 [10-139] | .591 |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 2,703 [324-6,270] | 2,135 [606-10,742] | 2,548 [324-10,742] | .498 |

| Symptomatic arrhythmia | 7 (28) | 4 (40) | 11 (30.5) | .689 |

| Triggering arrhythmia | ||||

| AF | 17 (69) | 9 (82) | 26 (72) | .688 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 8 (32) | 2 (18) | 10 (27) | .688 |

| Permanent AF | 9 (36) | 7 (64) | 16 (44) | .159 |

| Flutter | 7 (28) | 2 (18) | 9 (25) | .690 |

| VE | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 |

| HR at diagnosis, bpm | 142 ± 30 | 141 ± 20 | 142 ± 27 | .926 |

| NYHA class at treatment initiation | ||||

| I | 6 (24) | 2 (18) | 8 (22) | .402 |

| II | 8 (32) | 3 (27) | 11 (30) | .402 |

| III | 9 (36) | 3 (27) | 12 (33) | .402 |

| IV | 2 (8) | 3 (27) | 5 (14) | .402 |

| QRS width at initiation of treatment, ms | 96 ± 21 | 97 ± 25 | 97 ± 22 | .929 |

| LVEF at treatment initiation, % | 32 ± 10 | 34 ± 8 | 33 ± 9 | .598 |

| LVEDD, mm | 55.4 ± 7.8 | 57.3 ± 4.8 | 56.0 ± 6.9 | .501 |

| MR-LVEDV, mL | 208 ± 52 | 193 ± 48 | 202 ± 49 | .554 |

| MR-RVEDV, mL | 161 ± 36 | 146 ± 59 | 155 ± 44 | .526 |

| Follow-up, y | 2.11 ± 2.03 | 5.60 ± 3.15 | 3.17 ± 2.87 | .007 |

| Tachyarrhythmia ablation | 7 (28) | 0 | 7 (19) | .076 |

| AF ablation | 3 (12) | 0 | 3 (8) | .538 |

| Flutter ablation | 3 (12) | 0 | 3 (8) | .538 |

| VE ablation | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 |

| Time to LVEF recovery, y | 0.39 [0.21-0.75] | 1.13 [0.36-4.10] | 0.61 [0.21-1.51] | .041 |

| Time to relapse from treatment initiation, y | 3.08 [0.32-8.03] | |||

AF, atrial fibrillation; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR, magnetic resonance; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; RVEDV, right ventricular end-diastolic volume; VE, frequent ventricular extrasystole.

Values represent No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [range].

A: LVEF at initiation of treatment and after its complete recovery according to the presence of LVEF relapse during follow-up. B: Time to recovery of LVEF from initiation of treatment according to the presence of LVEF relapse during follow-up. C: LVEF relapse-free survival during follow-up in the total population (maroon) and in patients with and without AF. Log-rank test between subgroups with and without AF. AF, atrial fibrillation; Echo, echocardiography; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The present study represents the most extensive series of patients with TIC. Our data show that these patients have a significant future likelihood of relapse. These findings might be related to studies indicating residual subclinical damage in the form of interstitial fibrosis that causes relapses and/or adverse events during follow-up, even sudden death.1–3 This hypothesis has not been completely confirmed4 and, in our series, apart from the relapses, there were no sudden deaths or other complications.

Our study failed to identify any clinical, electrocardiographic, or cardiac imaging findings associated with worse prognosis, except a longer time from treatment initiation to LVEF recovery. Recent magnetic resonance studies indicate the ability of interstitial fibrosis on T1 mapping to predict poor prognosis.2 The magnetic resonance performed in our patients did not include this technique but the other parameters studied showed no associations with prognosis.

Clinical follow-up was significantly longer in patients with relapse, probably due to a need for more exhaustive monitoring.

In conclusion, patients with TIC can have ventricular function relapses years after their recovery. Our data, although limited by the small sample size and the retrospective nature of the study, indicate that TIC is probably not as benign as thought and requires long-term follow-up with exhaustive heart rate monitoring due to the relapse risk.

.