In this article, we describe 2 patients with Fontan circulation who underwent successful ablation of a hemodynamically unstable atrial arrhythmia with the aid of a continuous flow percutaneous ventricular assist device (VAD).

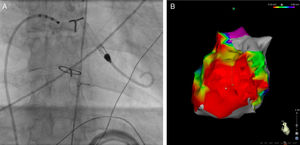

A 34-year-old man was referred to our clinic for an ablation for symptomatic, frequently-recurring intra-atrial reentrant tachycardia (IART). He was diagnosed with tricuspid atresia and atrial and ventricular septal defect. At the age of 8 years, a Fontan circulation had been created and resulted in a pulmonary homograft between the right atrium and a hypoplastic right ventricle (Björk modification). Preprocedure examination revealed moderately reduced left ventricular function and a mildly stenosed homograft. The first ablation procedure was discontinued due to hemodynamic instability. During the repeat procedure, we decided to use hemodynamic support through a percutaneous VAD (Impella 3.5 CP catheter, Abiomed Inc, Danvers, MA, United States), which was placed via the right femoral artery in a retrograde approach across the aortic valve in the left ventricle (Figure 1A). A dense bipolar voltage map (Figure 1B) of the right atrium identified scarring in multiple locations. An IART was induced and ablation was performed during tachycardia. During ablation on the lateral wall, the tachycardia terminated. However, multiple different IARTs could be reinduced. After ablation of all channels in the scar, no IART could be induced at the end of the procedure.

Radiographic image during the procedure (A), bipolar voltage map (B), case 1. A: a percutaneous ventricular assist device is placed via the right femoral artery in a retrograde approach across the aortic valve in the left ventricle. B: bipolar voltage map showing extensive scarring in the right atrium (right lateral view).

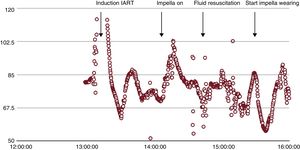

Initially, during atrial tachycardias, the patient was hemodynamically unstable. With a continuous blood flow of 2.7 L per minute, the tachycardias were tolerated, but only after correction of the preload. There have been no recurrences during a 30-month follow-up.

A 21-year-old man born with tricuspid valve atresia underwent a bidirectional Glenn anastomosis at 9 months. Completion of the Fontan circulation followed at the age of 2 when the right atrium was connected to the pulmonary artery.

The patient was referred for catheter ablation because of multiple episodes of drug-resistant IART. The patient had deteriorated left ventricular function and subsequently overt congested heart failure. Because he was hemodynamically unstable during his tachycardias, we used hemodynamic support with an Impella 3.5 CP catheter (Abiomed Inc, Danvers, MA, United States) that was placed via the left femoral artery.

Bipolar voltage mapping illustrated an area of low voltage on the lateral wall of the right atrium, most probably the result of the atriotomy. Entrainment mapping suggested that the area of low voltage on the lateral right atrial wall was part of the induced IART circuit. Consequently, an ablation line in the target area led to termination of the IART. With the use of the percutaneous VAD and preload correction by administrating 1.5 L lactated ringer's solution to obtain a left ventricular end diastolic pressure of more than 12mmHg, the patient maintained stable hemodynamics (Figure 2) and a urine production of > 200mL per hour.

The patient continued to receive sotalol twice daily and experienced a single episode of atrial tachycardia in the subsequent year. In addition, his ventricular function improved, symptoms of heart failure ceased, and his functional class remained stable.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report illustrating percutaneous circulatory left ventricle support as a human implant during complex atrial arrhythmia ablation in single-ventricle physiology.

Despite extended periods of hemodynamic instability during ablation, end-organ perfusion can be safely maintained by using circulatory support devices such as continuous flow percutaneous VAD. Hemodynamic support in VT ablation is widely accepted1 but is uncommon during ablation of atrial arrhythmias. Instability during ablation may vary according to the type of arrhythmia and underlying structural morphology.

In both single-ventricle patients, with the use of percutaneous VAD, resulting in a blood flow of 2.7 L/min and 3.5 L/min, respectively, stable blood pressure and cardiac output was maintained. This allowed for extensive mapping and ablation2 during prolonged periods of atrial arrhythmia without the development of hemodynamic compromise, as experienced by 1 of our patients in a previous ablation attempt.

Arrhythmias are a well-known long-term complication of the surgical repair of congenital heart defects, such as the Fontan operation.3 The pathophysiology is a complex interplay between cardiac anatomy, chamber enlargement due to abnormal pressure and volume loads, cellular injury from cardiopulmonary bypass, and fibrosis at sites of suture lines and patches.4 Cardiac failure due to loss of sinus rhythm was already recognized by Fontan in his first report.5

In conclusion, in single-ventricle patients with a Fontan-type repair, the use of percutaneous VAD combined with adequate preload results in stable cardiac output, facilitating mapping and ablation of atrial arrhythmias.

.