Limited information is available on the safety of pregnancy in patients with genetic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and in carriers of DCM-causing genetic variants without the DCM phenotype. We assessed cardiac, obstetric, and fetal or neonatal outcomes in this group of patients.

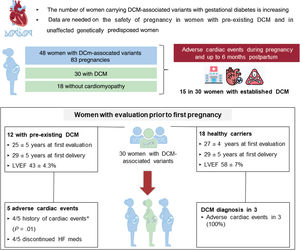

MethodsWe studied 48 women carrying pathogenic or likely pathogenic DCM-associated variants (30 with DCM and 18 without DCM) who had 83 pregnancies. Adverse cardiac events were defined as heart failure (HF), sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular assist device implantation, heart transplant, and/or maternal cardiac death during pregnancy, or labor and delivery, and up to the sixth postpartum month.

ResultsA total of 15 patients, all with DCM (31% of the total cohort and 50% of women with DCM) experienced adverse cardiac events. Obstetric and fetal or neonatal complications were observed in 14% of pregnancies (10 in DCM patients and 2 in genetic carriers). We analyzed the 30 women who had been evaluated before their first pregnancy (12 with overt DCM and 18 without the phenotype). Five of the 12 (42%) women with DCM had adverse cardiac events despite showing NYHA class I or II before pregnancy. Most of these women had a history of cardiac events before pregnancy (80%). Among the 18 women without phenotype, 3 (17%) developed DCM toward the end of pregnancy.

ConclusionsCardiac complications during pregnancy and postpartum were common in patients with genetic DCM and were primarily related to HF. Despite apparently good tolerance of pregnancy in unaffected genetic carriers, pregnancy may act as a trigger for DCM onset in a subset of these women.

Keywords

The increased availability of genetic testing for dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) has led to the identification of a growing number of individuals carrying DCM-associated genetic variants, including women of childbearing age with gestational desire.

Pregnancy and childbirth induce major physiological changes, requiring a progressive adaptation of the cardiovascular system.1,2 Pregnant women without heart disease can usually tolerate these hemodynamic changes well. However, in the presence of pre-existing DCM, pregnancy poses a risk of adverse cardiac events, such as heart failure (HF), arrhythmias, and even maternal death.2–4 Furthermore, DCM may be unmasked during pregnancy and the peripartum period in women with a genetic predisposition.5

Only a few studies focusing on the outcomes of pregnant women with pre-existing DCM have been published and they include only a limited number of patients. In these studies, women with DCM had a considerable risk of adverse cardiac events during pregnancy, especially among those with moderate-to-severe ventricular dysfunction and/or NYHA functional class III-IV, as observed in a prospective cohort of 32 women with idiopathic or doxorubicin-induced DCM.4 The information available in women with genetic DCM is scarce, and there is an even greater information gap among unaffected women with DCM-associated genetic variants attending clinics while planning pregnancy.

Given the lack of information on the safety of pregnancy in women with genetic DCM and unaffected genetic carriers, we aimed to assess cardiac, obstetric, and fetal and/or neonatal outcomes in women harboring DCM-causing variants and to describe the impact of pregnancy on DCM onset and clinical course.

METHODSWomen carrying a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in a DCM-associated gene were identified from the genetic databases of 9 referral centers (8 European and 1 Australian).

A chart review was performed to select women who had ever been pregnant. Data from the first and last clinical evaluations were retrospectively collected. Clinical, echocardiographic, and electrocardiographic data were recorded. DCM was defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%.6 Adverse cardiac events were defined as any of the following: HF symptoms requiring intravenous diuretics, sustained ventricular tachycardia (SVT), appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shock, left ventricular assist device implantation, heart transplant, and maternal cardiac death during pregnancy, or labor and delivery, and up to 6 months postpartum. Neurologic adverse events were also recorded. All events are reported.

Information was collected from all pregnancies, including maternal age, the presence of symptoms, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, medications taken before and during pregnancy, mode of delivery, and types of anesthesia/analgesia. The presence of complications during gestation (obstetric complications), labor and delivery, as well as fetal and neonatal adverse events, was collected.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed as mean±SD or as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical data are shown as percentages. For statistical analysis, the chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. The Student t test and Mann-Whitney nonparametric test were used in 2-group comparisons. A 2-sided P-value <.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was conducted using tStata SE package version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, United States).

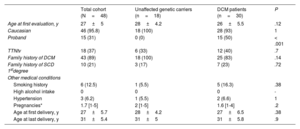

RESULTSA total of 48 women with DCM-associated variants were included, comprising 30 with overt DCM and 18 without cardiomyopathy (figure 1 of the supplementary data). Genetic variants were distributed among 12 genes, with the most frequent genes involved being TTN and LMNA (table 1 of the supplementary data). The total number of pregnancies was 83, with a median per patient of 1.7 [1–5]).

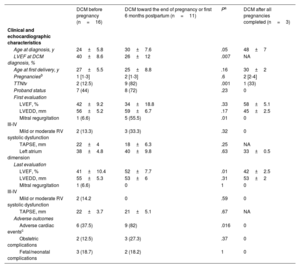

Women's baseline characteristics according to the presence of DCM were comparable, including the number of pregnancies and the age at first and last delivery (table 1). Adverse cardiac events were reported in 15 patients, all with established DCM at the time of the event (31% of the total cohort and 50% of women with DCM). Events included admissions due to HF and SVT. Of note, 4 DCM patients experienced neurologic events, and 1 died from HF despite advanced management and left ventricular assist device implantation (table 2). According to the timing of DCM diagnosis, women diagnosed toward the end of pregnancy or in the first months postpartum more frequently carried truncating variants in TTN (TTNtv), showed worse LVEF at diagnosis, and more frequently had cardiac complications than those with known DCM before their pregnancies (table 3).

Baseline characteristics of women with DCM-associated variants

| Total cohort (N=48) | Unaffected genetic carriers (n=18) | DCM patients (n=30) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first evaluation, y | 27±5 | 28±4.2 | 26±5.5 | .12 |

| Caucasian | 46 (95.8) | 18 (100) | 28 (93) | 1 |

| Proband | 15 (31) | 0 (0) | 15 (50) | < .001 |

| TTNtv | 18 (37) | 6 (33) | 12 (40) | .7 |

| Family history of DCM | 43 (89) | 18 (100) | 25 (83) | .14 |

| Family history of SCD 1stdegree | 10 (21) | 3 (17) | 7 (23) | .72 |

| Other medical conditions | ||||

| Smoking history | 6 (12.5) | 1 (5.5) | 5 (16.3) | .38 |

| High alcohol intake | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hypertension | 3 (6.2) | 1 (5.5) | 2 (6.6) | 1 |

| Pregnancies* | 1.7 [1-5] | 2 [1-5] | 1.6 [1-4] | .2 |

| Age at first delivery, y | 27±5.7 | 28±4.2 | 27±6.5 | .38 |

| Age at last delivery, y | 31±5.4 | 31±5 | 31±5.8 | .9 |

DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; SCD, sudden cardiac death; TTNtv, truncating variants in titin gene.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [range].

Maternal adverse outcomes in the entire cohort

| Maternal adverse outcomes | Any cardiac event | Heart failure | Arrhythmia | Cardiac death | Neurologic adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Timing of events | |||||

| During pregnancy | 6 | 5a | 1 | 1 | |

| Labor and delivery | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Initial 6 months postpartum | 8 | 6b | 1 | 1c | 2 |

Events occurred only in patients with overt DCM and not in unaffected variant carriers. Two pregnancies were complicated with 2 and 3 events. Neurologic events included 2 strokes toward the end of pregnancy in patients with HF, 1 stroke 3 months after delivery, and 1 transient ischemic attack during pregnancy.

Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics according to timing of DCM diagnosis in total cohort

| DCM before pregnancy (n=16) | DCM toward the end of pregnancy or first 6 months postpartum (n=11) | Pa | DCM after all pregnancies completed (n=3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, y | 24±5.8 | 30±7.6 | .05 | 48±7 |

| LVEF at DCM diagnosis, % | 40±8.6 | 26±12 | .007 | NA |

| Age at first delivery, y | 27±5.5 | 25±8.8 | .16 | 30±2 |

| Pregnanciesb | 1 [1-3] | 2 [1-3] | .6 | 2 [2-4] |

| TTNtv | 2 (12.5) | 9 (82) | .001 | 1 (33) |

| Proband status | 7 (44) | 8 (72) | .23 | 0 |

| First evaluation | ||||

| LVEF, % | 42±9.2 | 34±18.8 | .33 | 58±5.1 |

| LVEDD, mm | 56±5.2 | 59±6.7 | .17 | 45±2.5 |

| Mitral regurgitation III-IV | 1 (6.6) | 5 (55.5) | .01 | 0 |

| Mild or moderate RV systolic dysfunction | 2 (13.3) | 3 (33.3) | .32 | 0 |

| TAPSE, mm | 22±4 | 18±6.3 | .25 | NA |

| Left atrium dimension | 38±4.8 | 40±9.8 | .63 | 33±0.5 |

| Last evaluation | ||||

| LVEF, % | 41±10.4 | 52±7.7 | .01 | 42±2.5 |

| LVEDD, mm | 55±5.3 | 53±6 | .31 | 53±2 |

| Mitral regurgitation III-IV | 1 (6.6) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mild or moderate RV systolic dysfunction | 2 (14.2 | 0 | .59 | 0 |

| TAPSE, mm | 22±3.7 | 21±5.1 | .67 | NA |

| Adverse outcomes | ||||

| Adverse cardiac eventsc | 6 (37.5) | 9 (82) | .016 | 0 |

| Obstetric complications | 2 (12.5) | 3 (27.3) | .37 | 0 |

| Fetal/neonatal complications | 3 (18.7) | 2 (18.2) | 1 | 0 |

DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy, LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not available; RV, right ventricle; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TTNtv, truncating variants in titin gene.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

P comparisons of DCM before pregnancy and DCM toward the end of pregnancy or first months postpartum.

Defined as any of the following: heart failure (HF) requiring diuretic administration, sustained ventricular tachycardia, appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock, left ventricular assist device implantation, heart transplantation, and maternal cardiac death during pregnancy or labor and delivery and up to the sixth postpartum month.

A total of 6 out of 83 (7%) pregnancies were complicated by adverse obstetric events, and neonatal complications were reported in 6 pregnancies (7%); both were more frequent among patients with DCM (table 2 of the supplementary data). Complete information on deliveries was obtained in 56 pregnancies (34 women). Cesarean delivery was performed in 18 pregnancies (32%) in 10 women because of a cardiac indication (all in DCM patients) and in 8 women for obstetric reasons (3 in women with DCM). The remaining deliveries were vaginal without complications (38,67%).

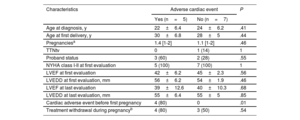

Women with prepregnancy evaluationA total of 30 women underwent cardiac assessment before their first pregnancy: 12 with DCM and 18 without cardiomyopathy. Women with pre-existing DCM (aged 25±5 years at the first evaluation; 29±5 years at the first delivery) showed left ventricular systolic dysfunction and mildly dilated left ventricles (LVEF 43±4.3%; LVEDD 55±4mm) at the baseline evaluation. All were in NYHA functional class I or II before pregnancy. Ten patients were on HF medication before pregnancy (9 on beta-blockers and 7 on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs], angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists [MRAs]). ACEIs/ARBs/MRAs and beta-blockers were discontinued in 7 and 3 patients, respectively. The 2 patients without any previous treatment were started on beta-blockers. Adverse cardiac events occurred in 5 women (42%): HF in 3 women, SVT requiring treatment in 2 women, and cardiac death in 1. One woman with HF also had preeclampsia. The only characteristic associated with adverse cardiac outcomes was a history of previous cardiac adverse events (table 4).

Characteristics of women with overt DCM before pregnancy according to the occurrence of adverse cardiac events

| Characteristics | Adverse cardiac event | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=5) | No (n=7) | ||

| Age at diagnosis, y | 22±6.4 | 24±6.2 | .41 |

| Age at first delivery, y | 30±6.8 | 28±5 | .44 |

| Pregnanciesa | 1.4 [1-2] | 1.1 [1-2] | .46 |

| TTNtv | 0 | 1 (14) | 1 |

| Proband status | 3 (60) | 2 (28) | .55 |

| NYHA class I-II at first evaluation | 5 (100) | 7 (100) | 1 |

| LVEF at first evaluation | 42±6.2 | 45±2.3 | .56 |

| LVEDD at first evaluation, mm | 56±6.2 | 54±1.9 | .46 |

| LVEF at last evaluation | 39±12.6 | 40±10.3 | .68 |

| LVEDD at last evaluation, mm | 55±6.4 | 55±5 | .85 |

| Cardiac adverse event before first pregnancy | 4 (80) | 0 | .01 |

| Treatment withdrawal during pregnancyb | 4 (80) | 3 (50) | .54 |

LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; TTNtv, truncating variants in titin gene.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

The 18 healthy women were mostly evaluated as part of family screening (n=16,88%; aged 27±4 years at the first evaluation; 29±5 years at the first delivery), had normal LVEF and LVEDD (58±7%; 48±4mm), and were completely asymptomatic in the period before their first pregnancy. Six women developed DCM after becoming pregnant: 3 toward the end of pregnancy (all showed HF in the final weeks of pregnancy and required cesarean section for a cardiac indication), and 3 years after initial and subsequent pregnancies (5, 9 and 27 years later). None received cardiac medications during pregnancy. The remaining 12 unaffected genetic carriers had uncomplicated pregnancies, showed a normal echocardiogram at the last follow-up, and had no adverse cardiac events, except for the occurrence of atrial fibrillation in 2 women several years after uneventful pregnancies. We found no clinical differences among women who developed DCM and those who did not after pregnancies (table 3 of the supplementary data). Detailed characteristics of women with prepregnancy evaluation who developed adverse cardiac events are presented in table 5.

Clinical characteristics of women with cardiac evaluation before first pregnancy with cardiac adverse events

| Patient | Variant | LVEF First evaluation, % | LVEF at diagnosis, % | Timing ofdiagnosis | NYHA leading into pregnancy | Age first delivery,years | LVEF last evaluation, % | NYHAlast evaluation | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women with established DCM | |||||||||

| 1 | DSP p.Pro2380Glnfs*11 | 45 | NA | 30 y before the first pregnancy | I | 40 | 32 | II | HF after delivery, cesarean for obstetric indication |

| 2 | DSP p.Ser2591Argfs*11 | 40 | 40 | 5 y before the first pregnancy | II | 26 | 43 | II | HF during pregnancy |

| 3 | RBM20p.Val911Met | 32 | 32 | 4 y before the first pregnancy | II | 27 | 20 | IV | HF toward the end of pregnancy, LVAD implant, stroke, cardiac death, cesarean for cardiac indication |

| 4 | LMNA p.Thr510Tyrfs*42 | 45 | 45 | 1 y before the first pregnancy | I | 26 | 54 | II | ICD appropriate shock during pregnancy |

| 5 | TPM1p.Leu113Val | 48 | 48 | 10 y before the first pregnancy | I | 38 | 40 | II | Aborted SCD 2 months after delivery |

| At-risk women | |||||||||

| 6 | MYH7p.Lys1445Glu | 51 | 27 | During pregnancy (last wk) | I | 25 | 49 | I | HF toward the end of pregnancy, cesarean for cardiac indication, VLBW |

| 7 | TTNp.Leu23499fs | 60 | 25 | During pregnancy (36th wk) | I | 25 | 63 | I | HF toward the end of pregnancy, cesarean for cardiac indication |

| 8 | TTN p.Ser2591Argfs*11 | 60 | 40 | During pregnancy (38th wk) | I | 27 | 57 | I | HF toward the end of pregnancy, cesarean for cardiac indication |

HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VLBW, very low birth weight (less than 1500 grams).

This study reports the cardiac, obstetric, and neonatal outcomes in 48 women with DCM-causing genetic variants with or without DCM (figure 1). In this cohort, pregnancy and postpartum were associated with a significant rate of cardiac complications, mostly related to HF (31% of the total cohort and 50% of women with overt DCM). Pregnancy was complicated with cardiac events in a high number of women who were known to have DCM before pregnancy (5 out of 12, 42%) despite showing NYHA class I or II before pregnancy. Of note, most of these women had a history of cardiac events before pregnancy. Among the 18 unaffected gene carriers who became pregnant, 3 (17%) developed DCM during pregnancy, and all of them had HF. Our results would be useful in advising the growing number of women with genetic DCM and unaffected genetic carriers who seek attention when considering gestational desire.

Central illustration. Cardiac outcomes in women with DCM-causing variants, both unaffected and with DCM phenotype. Adverse cardiac events were defined as any of the following: HF requiring diuretic administration, sustained ventricular tachycardia (SVT), appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shock, left ventricular assist device implantation, heart transplant, and maternal cardiac death during pregnancy or labor, or delivery and up to 6 months postpartum. A subgroup of 30 women with pre-pregnancy evaluation were analyzed. DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; HF, heart failure.

*History of cardiac events before the first pregnancy included HF in 3 patients and 1 patient with atrial fibrillation and an appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock.

The rate of cardiac complications found in our study is higher than that observed in the few studies that have examined similar groups of patients. A recent report of a retrospective cohort of 30 women with pathogenic or likely pathogenic DCM variants from Australia (16 without DCM and 14 with DCM) showed that most asymptomatic women had uncomplicated pregnancies; however, major cardiac adverse events within 6 months of pregnancy occurred in 10% of them, all in women with a DCM diagnosis during or shortly after pregnancy.7 Additionally, in a retrospective cohort of 60 women with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the gene encoding for lamin A/C proteins, pregnancy was well tolerated and did not seem to be associated with a worse long-term prognosis.8 A possible explanation for the discordant findings between these studies and ours is the higher number of patients with pre-existing DCM before pregnancy included in our cohort. It is expected that the hemodynamic challenge associated with pregnancy, as well as the deleterious effect of withdrawing HF medications contraindicated in pregnancy, would affect women with genetic DCM. Of note, the rate of cardiac complications observed in our study was similar to that reported in unselected DCM cohorts.3,4

According to our results, the most vulnerable period is the last few weeks of pregnancy or the first few postpartum months, and the occurrence of cardiac complications was highest among women diagnosed with DCM in this period. Similar findings were reported in the Australian study,7 in which all major cardiac adverse events occurred in women diagnosed with DCM during or shortly after pregnancy, despite being previously asymptomatic. Since the substantial overlap in genetic susceptibility between peripartum cardiomyopathy and DCM is well known,5 it is not clear whether these women had an undiagnosed DCM that manifested during pregnancy or if pregnancy acted as a second hit favoring cardiomyopathy development in women with a genetic predisposition. It is worth noting that TTNtv were more frequent in women with newly diagnosed DCM toward the end of pregnancy and postpartum, similar to the mutation yield reported in peripartum cardiomyopathy cohorts.5,9 Additionally, we observed a high need for cesarean sections for cardiac indication. Given that normal pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, as well as postpartum, are often associated with signs and symptoms that can easily overlap with those of HF, women with established genetic DCM require close monitoring and careful clinical assessment during pregnancy or labor and delivery, and should be closely followed up during the postpartum.

When assessing the risk of cardiac complications in women with DCM, some predictors of maternal cardiovascular events have been identified, such as the presence of moderate or severe left ventricular dysfunction and/or NYHA functional class III or IV.4,10 In this study, the rate of cardiac events among 12 women with overt DCM evaluated before their first pregnancy was high (42%), even though all women were in NYHA class I or II before pregnancy and had similar mean LVEF to women not developing cardiac complications. Of note, most patients with adverse events had a history of cardiac events before pregnancy, which is a recognized risk factor.2,11 In the small group of 18 at-risk women without DCM before pregnancy included in our study, 3 women (17%) developed symptomatic DCM at the end of their first pregnancy. However, pregnancy in genetic carriers not developing DCM was not associated with adverse cardiac events. With the identification of an increasing number of women with genetic variants seeking preconception counseling or embarking on pregnancy, further studies are necessary to find predictors of disease development and to stratify the risk of cardiac complications. Although this is the largest cohort of women with prepregnancy evaluation, the limited number of patients and the retrospective nature of this cohort restrict the power of the conclusions in a setting as complex as pregnancy and postpartum.

Last, the rate of obstetric complications and adverse fetal and/or neonatal events in this cohort was lower than previously described,4,12 even in women with established DCM. This could be explained by the better NYHA functional class of patients with DCM in our study.11

LimitationsThe limitations of the study include its retrospective nature, which precluded the collection of echocardiographic parameters before, during, and after pregnancy in all participants, as well as the assessment of repeat N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP] values to identify parameters that may play a role in outcomes. In addition, the study had a limited sample size. A total of 8 women diagnosed with DCM during their first pregnancy or postpartum did not undergo cardiac evaluation before pregnancy, and consequently we do not know if they exhibited DCM before. Last, because all participating centers are referral centers, we cannot exclude selection bias, particularly among unaffected genetic carriers who developed complications.

CONCLUSIONSCardiac complications during or shortly after pregnancy in patients with genetic DCM were common and mainly related to HF. In contrast, obstetric, and fetal and/or neonatal complications were uncommon. The most vulnerable women seemed to be those diagnosed at the end of pregnancy or the first few postpartum months. Among those with overt DCM, a history of cardiac events before pregnancy seems to be a risk factor for pregnancy-related new cardiac complications. These findings reinforce the need to offer appropriate preconception counseling and adequate cardiac surveillance in women with genetic DCM. Despite apparently good tolerance of pregnancy in unaffected genetic carriers, a group of genetically predisposed women developed DCM during pregnancy and postpartum. Further studies with a larger number of future mothers with genetic DCM, as well as unaffected women who are at risk leading into pregnancy, are needed to provide more precise information and facilitate counseling in this growing patient population.

- -

Studies on the outcomes of pregnant women with pre-existing DCM report cardiac complications in 16% to 39% of pregnancies.

- -

The number of women with genetic DCM is growing and no data are available on the safety of pregnancy in this population.

- -

Although asymptomatic women and unaffected women with rare DCM variants seem to tolerate pregnancy well, the impact of pregnancy on disease progression and the risk of cardiac complications remains unexplored.

- -

We found a nonnegligible rate of cardiac complications during or shortly after pregnancy in patients with genetic DCM, mainly related to HF. Those with a DCM diagnosis in the final weeks of pregnancy or the first postpartum months were the most vulnerable.

- -

A History of cardiac events before pregnancy was a risk factor for cardiac adverse events in our study.

- -

A small group of unaffected women with DCM-causing genetic variants developed symptomatic DCM during pregnancy and postpartum, underscoring the need to identify predictors for disease development in this population.

- -

These results highlight the need for women with genetic DCM or genetically predisposed to this disease to receive appropriate preconception counseling and close cardiac surveillance during pregnancy and postpartum.

P. Chmielewski and G. Truszkowska were supported by DETECTIN-HF grant from ERA-CVD framework, NCBiR. M. Kubánek was supported by the research grant MH CZ [NV19-08-00122], MH CZ-DRO (IKEM, IN 00023001) and by the National Institute for Research of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases project (EXCELES Programme, Project No. LX22NPO5104), Funded by the European Union-Next Generation EU. L.R. Lopes was supported by an MRC UK Clinical Academic Partnership Award (CARP) MR/T005181/1. MA Restrepo-Córdoba was supported by a grant from SEC-ROVI for the Promotion of Research in Heart Failure from the Heart Failure Section, Spanish Society of Cardiology. P. García-Pavía and M. Hazebroek are funded by the Pathfinder Cardiogenomics programme of the European Innovation Council of the European Union (DCM-NEXT project; project number: 101115416). The CNIC is supported by the ISCIII, MCIN, the Pro-CNIC Foundation, and the Severo Ochoa Centers of Excellence program (CEX2020-001041-S). The Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, the Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano-Isontina, the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, the Maastricht University Medical Center and the Expert Center for Rare Genetic Cardiovascular Diseases, Emergency Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases are members of the European Reference Network for Rare, Low Prevalence, and Complex Diseases of the Heart (ERN GUARD-Heart).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONSThe study was approved by the local ethics committees, which waived the need for informed consent from patients.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCENo artificial intelligence was used during the preparation of this work.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSThe authors confirm their contributions to the study as follows:

Concept and design: M.A. Restrepo-Córdoba, P. García-Pavía. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: all authors. Drafting the work: M.A. Restrepo-Córdoba, P. García-Pavía. Reviewing the work critically for important intellectual content: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTP. García-Pavía is associate editor of Rev Esp Cardiol. The journal's editorial procedure to ensure impartial processing of the manuscript has been followed. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.