This article presents data on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implants in Spain in 2023.

MethodsThe registry is based on information provided by centers following device implantation, which is submitted to the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology via the national online registry platform (Cardiodispositivos). Additional information sources include: a) data transfer from the manufacturing and marketing industry; and b) local databases sent from the implanting centers. Population data from the National Institute of Statistics for the first quarter of 2024 was used to calculate implant rates.

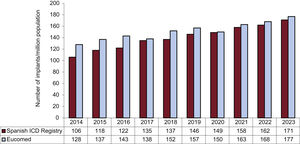

ResultsIn 2023, 180 hospitals participated in the registry. Data were reported for 8219 units, compared with 8523 reported by Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations). The total implant rate was 172 implants per million inhabitants (177 according to Eucomed), representing an increase compared with previous years. However, differences among autonomous communities persisted, and Spain continues to have the lowest implant rate among the European countries participating in Eucomed.

ConclusionsThe data from the 2023 registry reflects 96.4% of the implants performed in Spain. Despite the improvement observed in the implantation rate, Spain's position in Europe remains unchanged, with wide disparities among autonomous communities.

Keywords

Implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is associated with a reduced risk of sudden cardiac death in patients at high risk for this condition, either because they have a history of ventricular arrhythmia (secondary prevention) or because they are at risk of developing such arrhythmias (primary prevention). In addition, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) combined with an ICD (CRT-ICD) improves functional class, diminishes ventricular diameters, enhances left ventricular contractility, reduces hospitalizations, and decreases mortality in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction defects.1–3 Clinical practice guidelines list the indications for ICD therapy with and without CRT in the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias or at risk of developing them and include both primary and secondary prevention measures for sudden cardiac death.1–3 Sudden cardiac death is one of the leading causes of death in western countries. Recent data from the European Union show an incidence of sudden cardiac death of 60.4 cases/100 000 person-years, which represents a total of 309 792 cases/y and even 407 768 cases/y when including out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.4 In Spain, there are an estimated 30 000 cases annually, 40% of which occur in individuals younger than 65 years.5

The Spanish Implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator Registry has been published since 2005 and is drafted by members of the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC).6–8 The current article presents the data on ICD implantation in Spain reported to the registry in 2023.

METHODSThe registry is based on information voluntarily provided by participating centers and patients after device implantation, covering first implants and replacements. It is continuously compiled, updated, and maintained throughout the year with the participation of a team comprising full members of the Heart Rhythm Association and by the technical team and coordinator of the Heart Rhythm Association registries of the SEC. The device manufacturing and marketing industry also collaborate by transferring relevant data. All members have contributed to data cleaning and analysis and are responsible for this publication.

In accordance with Spanish legislation SCO/3603/2003 of December 18, and SSI/2443/2014, of December 17,9 2 partially automated files were created, named “National pacemaker registry” and “National implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry”. CardioDispositivos10 is the online platform of the Spanish National Pacemaker Registry and Spanish National Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Registry (owned by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products, Ministry of Health, Spanish Government). This platform has been managed by the SEC since 2016. Article 36 of Royal Decree 192/2023 of March 21 mandates that health care centers and professionals report specific data on pacemaker and defibrillator implantation to the abovementioned registries.11 In 2023, 6183 implants were reported via this route, representing 75.2% of the total. Other information sources include: a) data transfer from the manufacturing and marketing industry; b) Spanish implantable defibrillator patient identification cards; and c) local databases submitted by the implanting centers.

Census data for calculating rates per million population, both national and by autonomous community and province, were obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and refer to the first trimester of 2024.12 As in previous years, the data from the present registry were compared with those provided by the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (Eucomed).13

The percentages of each of the variables analyzed were calculated based on the total number of implants with available information on the parameter. Only the most serious condition was included if various types of arrhythmias were recorded.

Statistical analysisResults are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range], depending on the distribution of the variable. Continuous quantitative variables were analyzed using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test, while qualitative variables were analyzed using the chi-square test.

RESULTSAlthough 8523 procedures were reported by Eucomed, 8219 implantation forms were received in 2023 (representing 96.4% of all devices implanted in Spain).

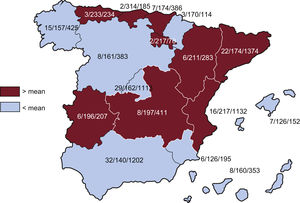

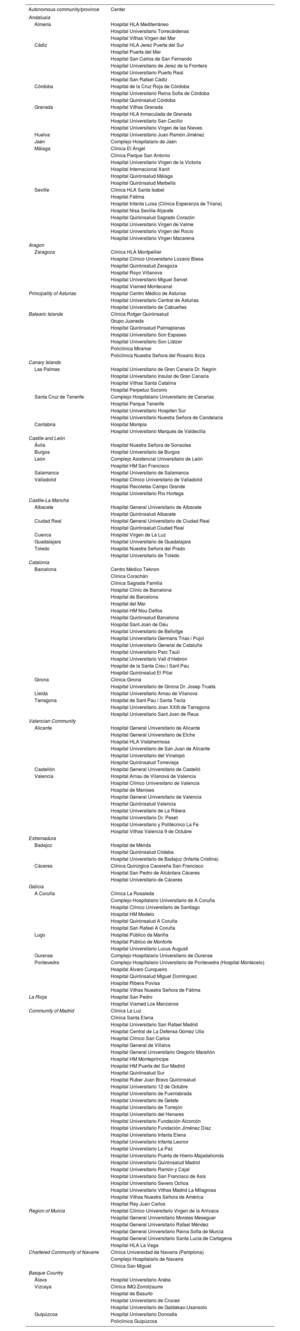

Implanting centersIn total, 180 hospitals participated in the registry in 2023, representing an increase from 2022 and the second highest participation since the inception of the registry (170 in 2022, 198 in 2021, 173 in 2020, 172 in 2019, and 173 in 2018). The 180 participating hospitals are listed in table 1. Figure 1 shows the total number of implanting centers, the rate per million population, and the total number of implants per autonomous community according to the data submitted to the registry. In 2023, 6 centers implanted more than 200 ICDs (5 centers in 2022). In total, 29 centers (25 in 2022) implanted ≥ 100 devices, 68 (67 in 2022) implanted between 11 and 99 devices, and 83 (78 in 2022) implanted ≤ 10. Of these, 26 (13 in 2022) implanted only 1 device. The vast majority of ICDs were implanted in public hospitals.

Implantation by autonomous community, province, and hospital

| Autonomous community/province | Center |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | |

| Almería | Hospital HLA Mediterráneo |

| Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas | |

| Hospital Vithas Virgen del Mar | |

| Cádiz | Hospital HLA Jerez Puerta del Sur |

| Hospital Puerta del Mar | |

| Hospital San Carlos de San Fernando | |

| Hospital Universitario de Jerez de la Frontera | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerto Real | |

| Hospital San Rafael Cádiz | |

| Córdoba | Hospital de la Cruz Roja de Córdoba |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Córdoba | |

| Granada | Hospital Vithas Granada |

| Hospital HLA Inmaculada de Granada | |

| Hospital Universitario San Cecilio | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves | |

| Huelva | Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez |

| Jaén | Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén |

| Málaga | Clínica El Ángel |

| Clínica Parque San Antonio | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | |

| Hospital Internacional Xanit | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Málaga | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Marbella | |

| Seville | Clínica HLA Santa Isabel |

| Hospital Fátima | |

| Hospital Infanta Luisa (Clínica Esperanza de Triana) | |

| Hospital Nisa Sevilla-Aljarafe | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Sagrado Corazón | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | |

| Aragon | |

| Zaragoza | Clínica HLA Montpellier |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Zaragoza | |

| Hospital Royo Villanova | |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | |

| Hospital Viamed Montecanal | |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Centro Médico de Asturias |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias | |

| Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes | |

| Balearic Islands | Clínica Rotger Quirónsalud |

| Grupo Juaneda | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Palmaplanas | |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | |

| Hospital Universitario Son Llàtzer | |

| Policlínica Miramar | |

| Policlínica Nuestra Señora del Rosario Ibiza | |

| Canary Islands | |

| Las Palmas | Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín |

| Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria | |

| Hospital Vithas Santa Catalina | |

| Hospital Perpetuo Socorro | |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias |

| Hospital Parque Tenerife | |

| Hospital Universitario Hospiten Sur | |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | |

| Cantabria | Hospital Mompía |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | |

| Castile and León | |

| Ávila | Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles |

| Burgos | Hospital Universitario de Burgos |

| León | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León |

| Hospital HM San Francisco | |

| Salamanca | Hospital Universitario de Salamanca |

| Valladolid | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid |

| Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande | |

| Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | |

| Castile-La Mancha | |

| Albacete | Hospital General Universitario de Albacete |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Albacete | |

| Ciudad Real | Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Ciudad Real | |

| Cuenca | Hospital Virgen de La Luz |

| Guadalajara | Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara |

| Toledo | Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado |

| Hospital Universitario de Toledo | |

| Catalonia | |

| Barcelona | Centro Médico Teknon |

| Clínica Corachán | |

| Clínica Sagrada Família | |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona | |

| Hospital de Barcelona | |

| Hospital del Mar | |

| Hospital HM Nou Delfos | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Barcelona | |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Déu | |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge | |

| Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol | |

| Hospital Universitario General de Cataluña | |

| Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí | |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d‘Hebron | |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud El Pilar | |

| Girona | Clínica Girona |

| Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | |

| Lleida | Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova |

| Tarragona | Hospital de Sant Pau i Santa Tecla |

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII de Tarragona | |

| Hospital Universitario Sant Joan de Reus | |

| Valencian Community | |

| Alicante | Hospital General Universitario de Alicante |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | |

| Hospital HLA Vistahermosa | |

| Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante | |

| Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Torrevieja | |

| Castellón | Hospital General Universitario de Castelló |

| Valencia | Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | |

| Hospital de Manises | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Valencia | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Valencia | |

| Hospital Universitario de La Ribera | |

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset | |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe | |

| Hospital Vithas Valencia 9 de Octubre | |

| Extremadura | |

| Badajoz | Hospital de Mérida |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Clideba | |

| Hospital Universitario de Badajoz (Infanta Cristina) | |

| Cáceres | Clínica Quirúrgica Cacereña San Francisco |

| Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara Cáceres | |

| Hospital Universitario de Cáceres | |

| Galicia | |

| A Coruña | Clínica La Rosaleda |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña | |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago | |

| Hospital HM Modelo | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud A Coruña | |

| Hospital San Rafael A Coruña | |

| Lugo | Hospital Público da Mariña |

| Hospital Público de Monforte | |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti | |

| Ourense | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense |

| Pontevedra | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra (Hospital Montecelo) |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Miguel Domínguez | |

| Hospital Ribera Povisa | |

| Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de Fátima | |

| La Rioja | Hospital San Pedro |

| Hospital Viamed Los Manzanos | |

| Community of Madrid | Clínica La Luz |

| Clínica Santa Elena | |

| Hospital Universitario San Rafael Madrid | |

| Hospital Central de La Defensa Gómez Ulla | |

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos | |

| Hospital General de Villalva | |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | |

| Hospital HM Montepríncipe | |

| Hospital HM Puerta del Sur Madrid | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Sur | |

| Hospital Ruber Juan Bravo Quirónsalud | |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | |

| Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | |

| Hospital Universitario de Torrejón | |

| Hospital Universitario del Henares | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz | |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor | |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda | |

| Hospital Universitario Quirónsalud Madrid | |

| Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal | |

| Hospital Universitario San Francisco de Asís | |

| Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa | |

| Hospital Universitario Vithas Madrid La Milagrosa | |

| Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de América | |

| Hospital Rey Juan Carlos | |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca |

| Hospital General Universitario Morales Meseguer | |

| Hospital General Universitario Rafael Méndez | |

| Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía de Murcia | |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena | |

| Hospital HLA La Vega | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Clínica Universidad de Navarra (Pamplona) |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra | |

| Clínica San Miguel | |

| Basque Country | |

| Álava | Hospital Universitario Araba |

| Vizcaya | Clínica IMQ Zorrotzaurre |

| Hospital de Basurto | |

| Hospital Universitario de Cruces | |

| Hospital Universitario de Galdakao-Usansolo | |

| Guipúzcoa | Hospital Universitario Donostia |

| Policlínica Guipúzcoa | |

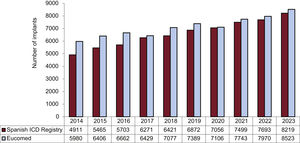

The total number of implants reported to the registry and those estimated by Eucomed in the last 10 years are shown in figure 2. In 2023, 8219 implants were recorded (including first implants and replacements), marking a historic high for the registry and representing a 6.8% increase vs the previous year (7693 units were recorded in 2022). In addition, the data provided by Eucomed (8523 implants in 2023) also showed the highest numbers of implants since the inception of the registry, with a 7% increase vs 2022 (Eucomed reported 7970 implants in Spain in 2022).

Changes in the implantation rate per million population in the last 10 years according to registry and Eucomed data are shown in figure 3. The implantation rate recorded in 2023 was 171 implants per million population but 177 per million population according to Eucomed data. These values exceed those reported to the registry and reported by Eucomed in previous years (168 implants/million population in 2022, 163 in 2021, 150 in 2020, and 157 in 2019).

First implants vs replacementsFirst implants and replacements were distinguished in 6268 forms (76% of devices included in the registry). First implants comprised 72% of devices implanted, while replacements represented 28% of recorded activity. These values are similar to those of previous registries (71.9% for first implants in 2022 and 70.3% in 2021). This figure equals a rate of first implants per million population of 121.5 (116 in 2022 and 110 in 2021).

Age and sexIn 2023, the mean age of the patients included in the registry was 62.5±13.7 (range, 2-92) years. As in previous years, first implant recipients were slightly younger (61.2±13.4 years) and overwhelmingly male, at 82.5% of all patients and 83.2% of first implant recipients.

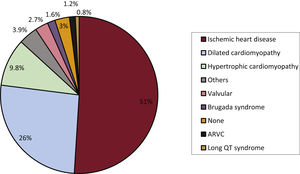

Underlying heart disease, left ventricular ejection fraction, functional class, and baseline rhythmThe underlying heart diseases in the registry patients (first implants and replacements) are shown in figure 4. Ischemic heart disease was the most frequent underlying heart disease in first implant patients (51%), followed by dilated cardiomyopathy (26%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (9.8%), primary electrical abnormalities (Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia) (2.5%), valve disease (2.7%), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (1.2%).

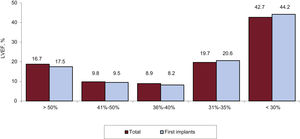

Left ventricular systolic function data were provided in 36% of forms. As shown in figure 5, most patients had a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 35%.

Most registry patients (66.9%) were in New York Heart Association class II, followed by NYHA III (18.1%) and NYHA I (15%). In the 2023 registry, no patient was in NYHA IV. Once again, the distribution of this variable was similar in the overall and first implantation groups.

The baseline rhythm shown by patients at implantation (available in 52.3% of forms) was mainly sinus rhythm (81.4%), followed by atrial fibrillation (16.4%) and pacemaker rhythm (2.2%).

Clinical arrhythmias prompting implantation, clinical presentation, and arrhythmias induced in the electrophysiological laboratory

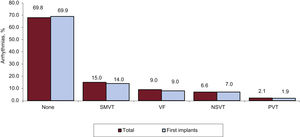

The clinical arrhythmias prompting ICD implantation (available in 2425 forms submitted to the registry) are shown in figure 6. Most first implant patients had no documented arrhythmia (69.9%).

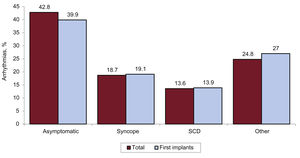

The most frequent clinical presentation in patients with ICD implantation was asymptomatic (in about 42.8% of patients), followed by other symptoms, syncope, and aborted sudden cardiac death (figure 7).

In a small percentage of cases (2.6%), an electrophysiological study was conducted before ICD implantation. Such studies were most commonly performed for ischemic heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (a cause of 80% of pre-ICD implant studies). Sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia was the most common induced arrhythmia (67.6%), followed by ventricular fibrillation (18.5%), nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (9.3%), and, to a lesser extent, other arrhythmias (4.6%). No arrhythmia was induced in 43.7% of the electrophysiological studies.

Clinical historyThe Spanish ICD Registry incorporates data on the clinical characteristics of ICD recipients in Spain (this information was specified in 54.1% of forms). The patients included in the registry had hypertension (38.9% of all cases), hypercholesterolemia (33.3%), smoking (25.1%), diabetes mellitus (23.3%), a history of atrial fibrillation (22.4%), renal failure (8.1%), a family history of sudden cardiac death (5.3%), and a history of stroke (3.4%).

QRS duration (mean, 131.4ms) was reported for 32.2% of first implants. The duration was >140ms in 35.2% of patients and most patients received a resynchronization defibrillator device (82.4%).

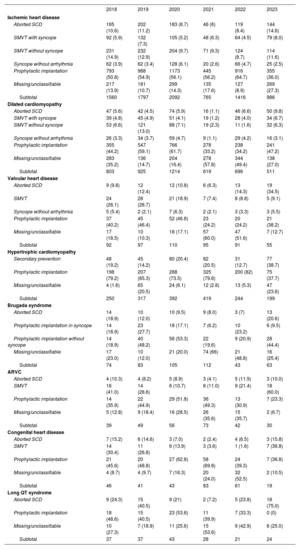

IndicationsDevice indications and their variations are shown in table 2. These data were provided in 59% of forms in 2023. Ischemic heart disease was the most common cardiac condition prompting ICD implantation in Spain. Among patients with ischemic heart disease, the most frequent indication was primary prevention. The second most common reason for ICD implantation was dilated cardiomyopathy. As can be seen in table 2, in 2023, there was a repeat of the 2022 fall in the absolute number of first implants vs previous years (696 in 2022, 619 in 2021, 1214 in 2020, and 925 in 2019). For the less common heart diseases, the most frequent indication was primary prevention.

Number of first implants according to the type of heart disease, type of clinical arrhythmia, and form of presentation from 2018 to 2023

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 165 (10.6) | 202 (11.2) | 183 (8.7) | 46 (6) | 119 (8.4) | 144 (14.6) |

| SMVT with syncope | 92 (5.9) | 132 (7.3) | 105 (5.2) | 48 (6.3) | 64 (4.5) | 79 (8.0) |

| SMVT without syncope | 231 (14.9) | 232 (12.9) | 204 (9.7) | 71 (9.3) | 124 (8.7) | 114 (11.6) |

| Syncope without arrhythmia | 62 (3.9) | 62 (3.4) | 128 (6.1) | 20 (2.6) | 66 (4.7) | 25 (2.5) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 793 (50.8) | 988 (54.9) | 1173 (56.1) | 445 (56.2) | 916 (64.7) | 355 (36.0) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 217 (13.9) | 181 (10.7) | 299 (14.3) | 135 (17.6) | 127 (8.9) | 269 (27.3) |

| Subtotal | 1560 | 1797 | 2092 | 765 | 1416 | 986 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 47 (5.6) | 42 (4.5) | 74 (5.9) | 16 (1.1) | 46 (6.6) | 50 (9.8) |

| SMVT with syncope | 39 (4.8) | 45 (4.9) | 51 (4.1) | 19 (1.2) | 28 (4.0) | 34 (6.7) |

| SMVT without syncope | 53 (6.6) | 121 (13.0) | 88 (7.1) | 19 (2.3) | 11 (1.6) | 32 (6.3) |

| Syncope without arrhythmia | 26 (3.3) | 34 (3.7) | 59 (4.7) | 9 (1.1) | 29 (4.2) | 16 (3.1) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 355 (44.2) | 547 (59.1) | 766 (61.7) | 278 (33.2) | 238 (34.2) | 241 (47.2) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 283 (35.2) | 136 (14.7) | 204 (16.4) | 278 (57.8) | 344 (49.4) | 138 (27.0) |

| Subtotal | 803 | 925 | 1214 | 619 | 696 | 511 |

| Valvular heart disease | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 9 (9.8) | 12 (12.4) | 12 (10.8) | 6 (6.3) | 13 (14.3) | 19 (34.5) |

| SMVT | 24 (26.1) | 28 (28.7) | 21 (18.9) | 7 (7.4) | 8 (8.8) | 5 (9.1) |

| Syncope without arrhythmia | 5 (5.4) | 2 (2.1) | 7 (6.3) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (5.5) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 37 (40.2) | 45 (46.4) | 52 (46.8) | 23 (24.2) | 20 (24.2) | 21 (38.2) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 17 (18.5) | 10 (10.3) | 18 (17.1) | 57 (60.0) | 47 (51.6) | 7 (12.7) |

| Subtotal | 92 | 97 | 110 | 95 | 91 | 55 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | ||||||

| Secondary prevention | 48 (19.2) | 45 (14.2) | 80 (20.4) | 82 (20.5) | 31 (12.7) | 77 (38.7) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 198 (79.2) | 207 (65.3) | 288 (73.5) | 325 (79.8) | 200 (82) | 75 (37.7) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 4 (1.6) | 65 (20.5) | 24 (6.1) | 12 (2.8) | 13 (5.3) | 47 (23.6) |

| Subtotal | 250 | 317 | 392 | 419 | 244 | 199 |

| Brugada syndrome | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 14 (18.9) | 10 (12.0) | 10 (9.5) | 9 (8.0) | 3 (7) | 13 (20.6) |

| Prophylactic implantation in syncope | 14 (18.9) | 23 (27.7) | 18 (17.1) | 7 (6.2) | 10 (23.2) | 6 (9.5) |

| Prophylactic implantation without syncope | 14 (18.9) | 40 (48.2) | 56 (53.3) | 22 (19.6) | 9 (20.9) | 28 (44.4) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 17 (23.0) | 10 (12.0) | 21 (20.0) | 74 (66) | 21 (48.8) | 16 (25.4) |

| Subtotal | 74 | 83 | 105 | 112 | 43 | 63 |

| ARVC | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 4 (10.3) | 4 (8.2) | 5 (8.9) | 3 (4.1) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (10.0) |

| SMVT | 16 (41.0) | 14 (28.6) | 6 (10.7) | 8 (11.0) | 9 (21.4) | 18 (60.0) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 14 (35.9) | 22 (44.9) | 29 (51.8) | 36 (49.3) | 13 (30.9) | 7 (23.3) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 5 (12.8) | 9 (18.4) | 16 (28.5) | 26 (35.6) | 15 (35.7) | 2 (6.7) |

| Subtotal | 39 | 49 | 56 | 73 | 42 | 30 |

| Congenital heart disease | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 7 (15.2) | 6 (14.6) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (6.5) | 3 (15.8) |

| SMVT | 14 (30.4) | 11 (26.8) | 6 (13.9) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.6) | 7 (36.8) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 21 (45.6) | 20 (48.8) | 27 (62.8) | 58 (69.8) | 24 (39.3) | 7 (36.8) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 4 (8.7) | 4 (9.7) | 7 (16.3) | 20 (24.0) | 32 (52.5) | 2 (10.5) |

| Subtotal | 46 | 41 | 43 | 83 | 61 | 19 |

| Long QT syndrome | ||||||

| Aborted SCD | 9 (24.3) | 15 (40.5) | 9 (21) | 2 (7.2) | 5 (23.8) | 18 (75.0) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 18 (48.6) | 15 (40.5) | 23 (53.6) | 11 (39.9) | 7 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 10 (27.3) | 7 (18.9) | 11 (25.6) | 15 (53.6) | 9 (42.9) | 6 (25.0) |

| Subtotal | 37 | 37 | 43 | 28 | 21 | 24 |

ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SMVT, sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

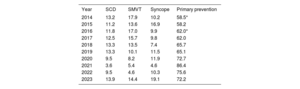

In the 2023 registry, primary prevention of sudden cardiac death was the main indication for first ICD implants (72.2%), followed by syncope (19.1%), sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (14.4%), and aborted sudden cardiac death (13.9%) (table 3). Despite the reduction in primary prevention as an indication for ICD implantation vs 2021 (86.4%), it remained above 70% (table 3).

Variation in the main indications for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (first implants, 2014-2023)

| Year | SCD | SMVT | Syncope | Primary prevention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 13.2 | 17.9 | 10.2 | 58.5* |

| 2015 | 11.2 | 13.6 | 16.9 | 58.2 |

| 2016 | 11.8 | 17.0 | 9.9 | 62.0* |

| 2017 | 12.5 | 15.7 | 9.8 | 62.0 |

| 2018 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 7.4 | 65.7 |

| 2019 | 13.3 | 10.1 | 11.5 | 65.1 |

| 2020 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 11.9 | 72.7 |

| 2021 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 86.4 |

| 2022 | 9.5 | 4.6 | 10.3 | 75.6 |

| 2023 | 13.9 | 14.4 | 19.1 | 72.2 |

SCD, sudden cardiac death; SMVT, sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

The implantation setting and specialist performing the procedure were recorded in 75.2% and 72.3% of forms, respectively. Overall, 84% of procedures were performed in electrophysiology laboratories and 14% in operating rooms. An electrophysiologist implanted the device in 86% of cases, a surgeon in 5%, an intensivist in 4%, a cardiologist in 4%, and a combination of specialists in 1%.

Generator placement siteTransvenous ICD generator placement was reported in 67.4% of forms: subcutaneous in 92.5% of cases and subpectoral in the remaining 7.5%.

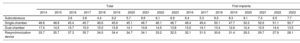

Device typeThe types of implanted devices are shown in table 4. A stabilization was detected in subcutaneous ICD implantation at about 7% of implants. The most frequently implanted devices were single-chamber ICDs (50.7%), followed by CRT-ICDs (28.1%) and dual-chamber ICDs (13.5%).

Percent distribution of implanted devices by type

| Total | First implants | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Subcutaneous | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 7.7 | ||

| Single-chamber | 48.8 | 48.6 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 46.6 | 45.6 | 45.1 | 46.7 | 46.1 | 46.7 | 48.4 | 49.4 | 50.1 | 47.7 | 50.2 | 52.6 | 51.1 | 50.7 |

| Dual-chamber | 17.4 | 14.5 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 13.8 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 14.1 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 10.5 | 14.4 | 13.5 |

| Resynchronization device | 33.7 | 35.7 | 37.3 | 35.7 | 34.0 | 34.4 | 34.7 | 34.1 | 33.2 | 32.5 | 32.1 | 31.5 | 30.6 | 31.4 | 29.3 | 29.7 | 27.9 | 28.1 |

As in previous years, the most frequent reason for ICD generator replacement was battery depletion (70.6%), followed by an upgrade (15.6% of cases). In addition, replacement was due to device dysfunction in 3.2% of cases and infection in 1.7%. The reason was not specified in the remaining 8.9%. Finally, 23 instances of lead dysfunction were reported to the registry.

Device programmingWith data on 52.5% of implants, the most commonly used pacing mode was VVI (40.3%), followed by DDD (20.3%), VVIR (4.8%), and DDDR (4.7%). Resynchronization was specified in 8.3% of cases and other modes in 12.5%. These modes typically reflect algorithms or modes to prevent ventricular pacing.

Postimplantation induction of ventricular fibrillation was performed at least once in 312 patients, mainly in patients with a subcutaneous ICD (273 patients) and in only 39 patients with a transvenous ICD. The mean number of shocks delivered was 1.09 and the mean threshold was 63.4 Ω, which would reflect the greater use of subcutaneous ICDs.

ComplicationsComplication data were included in 53.1% of forms. A total of 201 complications were recorded: 7 subacute lead displacements, 6 coronary sinus dissections, 6 suboptimal left ventricular electrode positions, 3 cases of pneumothorax, 1 tamponade, 1 death, and 177 unspecified complications.

DISCUSSIONThe 2023 Spanish Implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator Registry report is the 20th since the inception of the registry in 2005 and shows the highest ICD implantation activity in its history, at 171 ICDs per million population (177 according to Eucomed data). As in previous years, major differences are evident in implantation rates among autonomous communities and, despite the increase in the number of units implanted, ICD implantation rates are still much lower than the European average (300 units/million population in 2022).

Comparison with registries of previous yearsParalleling the rise in the number of ICDs implanted in Spain in 2023, there was an increase in the number of hospitals participating in the registry. This marks the second consecutive year of greater participation by Spanish hospitals, with the registry capturing almost all implants performed in Spain in 2023 (96.4% of the total).

Since the registry began, the number of implanted ICDs has progressively increased, with periodic reductions in 2011/2012, 2017, and 2020. In 2020, ICD implants fell by 4% vs previous years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospital activity recovered in subsequent years and the data for 2023 confirm the normalization of activity and indicate the highest number of ICD implants since registry foundation.

However, the mean ICD implantation rate per million population (177 implants per million) in Spain is the lowest of all European Union countries and remains far below the European average of 300 implants per million population in 2022. According to these figures, ICD implants in Spain remain less frequent than expected given the scientific evidence underpinning clinical practice guidelines.1–3 This situation is not unique to Spain, and studies performed in other health care systems show ICD treatment rates much lower than expected according to guidelines. Data from various American databases show ICD and CRT-ICD implantation rates of 15% and 41% of theoretical indications according to clinical practice guidelines.14 A study performed in Sweden15 revealed that only 10% of patients with an ICD indication for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death (according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines) between 2000 and 2016 ultimately received a device.15 The results also linked ICD implantation to a 27% reduction in mortality. Recently published observational data that consider the experience of patients already treated with drugs such as sacubitril-valsartan and sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors also reveal the underuse of ICDs (8.4% of all theoretical indications) and a highly significant reduction in mortality in ICD recipients during a 5-year follow-up (37.6% vs 44.7% in those who did not receive an ICD).16 These data indicate that the main consequence of ICD underuse is be increased mortality in patients who could benefit from this therapy. The Spanish Implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator Registry shows the clear underuse of ICD therapy in Spain. While the reasons are difficult to explain, the results highlight the need for new measures to increase ICD use in patients who would benefit from the therapy.

Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death was the main reason for ICD implantation in Spain; in 2023, this indication accounted for 72.2% of first implants. These values are similar to those of recent years, which were all above 70%. In the last 10 years, the prophylactic indication has increased by more than 50% and it is now similar to that of neighboring countries, where primary prevention is the main indication for ICD implantation, with values at about 80%.17,18

As in previous years, single-chamber ICDs were the most frequently implanted devices in Spain and were used in 50% of first implants. In 2023, the data confirmed a reduction in first implants of CRT-ICD devices, which have remained below 30% since 2020. In addition, a stabilization was detected in the percentages of dual-chamber and subcutaneous ICDs (7.7% in 2023). The greater use of these devices is limited by the inability of subcutaneous ICDs to use antitachycardia pacing to treat ventricular arrhythmias. Nonetheless, in May 2024, an evaluation was published of a new modular system that combines a subcutaneous ICD with a leadless pacemaker that allows wireless communication between the 2 devices.19 This system permits antitachycardia pacing through unidirectional communication from the subcutaneous ICD to the leadless pacemaker. Assessment of the system showed the safety and efficacy of the combined use of the 2 devices and the reliability of their intercommunication.19 In 2023, the European Union approved the use of a new extravascular ICD that enables ventricular pacing to deliver pause-prevention pacing and antitachycardia therapies.20 The first of these devices was implanted in Spain in November 2023. The coming years will reveal the impact of these new devices on the types of ICDs implanted.

The most frequent ICD indication in 2023 remained ischemic heart disease, followed by dilated cardiomyopathy. Both conditions represent more than 75% of all ICD indications prompting implantation in Spain. As in 2022, there was a reduction in 2023 in ICD implants in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, which also manifested in a reduction in the number of prophylactic ICD indications for this condition. This likely explains the reduction seen in the percentage of CRT-ICD devices implanted in 2023. Various publications may explain these figures. In addition to the DANISH study,21 the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure from 20213 and for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death from 20222 have reduced the level of recommendation for ICDs in the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (IIa A). However, the indication for ICD therapy in dilated cardiomyopathy remains controversial. The heart failure guidelines acknowledge possible benefits of ICDs in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy aged <70 years, in whom a publication from the same study showed a 30% reduction in mortality.3 In addition, the guidelines incorporate the results of a meta-analysis including the DANISH trial, in which ICDs were found to reduce all-cause mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy.22

Moreover, the guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias propose the use of genetic analysis to identify mutations associated with an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death and the detection of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to improve the risk stratification of sudden cardiac death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.2 In 2023, the European Society of Cardiology published new clinical practice guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies.23 These guidelines define a new entity, nondilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy, which involves ventricular dysfunction and/or pathological uptake of gadolinium without ventricular dilatation. The guidelines consider ICD implantation (IIa C recommendation) in both dilated and nondilated cardiomyopathy in the presence of mutations associated with an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death and/or late gadolinium uptake on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction both below and above 35%.

Finally, a Spanish cost-effectiveness analysis24 of ICDs in the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death showed that ICD therapy is associated with reduced all-cause death in both ischemic heart disease (hazard ratio=0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-0.85) and nonischemic heart disease (hazard ratio=0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.96). Using probabilistic analysis, the study estimated cost-effectiveness ratios of 19 171 euros per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) in patients with ischemic heart disease, 31 084 euros/QALY in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, and 23 230 euros/QALY in individuals younger than 68 years. These results confirm the effectiveness of ICDs in Spain in the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with left ventricular dysfunction of both ischemic and nonischemic origin, particularly in patients younger than 68 years.

Differences among autonomous communitiesAs in previous years, the 2023 registry revealed considerable differences among autonomous communities in the implantation rate per million population. Several communities showed higher than average rates: Cantabria (314/million population), the Principality of Asturias (233), La Rioja (217), the Valencian Community (217), Aragon (211), Castile-La Mancha (197), Extremadura (196), the Basque Country (174), and Catalonia (174). Below-average rates were seen in the Chartered Community of Navarre (170/million population), Community of Madrid (162), Castile and León (161), the Canary Islands (160), Galicia (158), Andalusia (140), the Balearic Islands (126), and the Region of Murcia (126). As is evident from these figures, the autonomous community with the highest implantation rate implanted more than twice as many ICDs as the 2 autonomous communities with the lowest implantation rates and almost 200 more devices. The disparity in the ICD implantation rate among the autonomous communities in the supposedly uniform Spanish health care system remains a puzzle and indicates that the same criteria are not being applied to ICD implantation, despite the available evidence and the work of the SEC. These differences are not explained by income level or population density or by the different incidences of ischemic heart disease and heart failure among the autonomous communities. This situation calls into question the equity of the Spanish health care system in an area as important as the prevention of sudden cardiac death.

Comparison with other countriesA comparison of the data with those of other European countries participating in Eucomed once again showed that Spain has a lower rate of ICD implants per million population. In 2022, the number of ICD implants per million population in Eucomed participants was 300 (including ICDs and CRT-ICDs). This figure exceeds the 296 and 285 implants per million population recorded in 2021 and 2020 (the year with the greatest impact of the COVID-19 pandemic) and approximates the values of the previous years (303 in 2019, 302 in 2018, 307 in 2017, and 316 in 2016). The countries with the highest implant numbers were the Czech Republic, Italy, and Germany (437, 437, and 436 devices per million population, respectively). Spain remains the country with the lowest number of implants per capita (177 implants/million population in 2023). This figure is lower than that of the other European countries with low ICD implantation activity, such as Hungary, the United Kingdom, and Portugal (180, 200, and 251 implants per million population in 2022).

There are probably many complex reasons for this situation. One possible explanation is the number of available arrhythmia units, but that does not explain the relationship, at least in Spain, because communities with the highest number of available units had lower implantation rates. Income does not seem to be a factor because countries with lower incomes than Spain, such as Ireland, the Czech Republic, and Poland, show much higher implantation rates. Nor can this disparity be explained by differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. For example, Mediterranean countries such as Portugal and Italy show a much higher implantation rate, with Italy in particular doubling the Spanish figures.

LimitationsIn 2023, our registry collected data on 96.4% of all implants, representing the vast majority of ICDs implanted in Spain. As in previous years, the completion of the different fields in the implantation form varied and remained lower than desired. Although a web platform for recording pacemaker and ICD device implantation has been available since 2019,10 reporting is inconsistent. In addition, the registry does not collect valuable ICD programming data that would be associated with patients’ morbidity and mortality, such as detection times, heart rate thresholds, and the intervals at which supraventricular rhythm discriminators operate, all of which help reduce both appropriate and inappropriate therapies. In addition, no follow-up data were collected from patients, which would permit more relevant clinical studies. Finally, inconsistent completion of data on ICD implantation-related complications and the lack of follow-up data likely led to an underestimation of the true rate of complications.

Future prospects of the Spanish implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registryThis is the 20th official report of the registry, and its longevity is a credit to all the participating members of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC, particularly given that this is the only registry of its type in Europe. At the same time, all hospitals should commit to ensuring the completion of the data included in the registry. The use of CardioDispositivos, the online platform of the Spanish National Pacemaker Registry and the National Implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator Registry (owned by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products, Ministry of Health, Spanish Government) and managed by the SEC since 2016, differs among Spanish implanting centers, despite the requirement to provide data under Royal Decree 192/2023.10 The viability of the registry relies on all participating centers recognizing the importance of submitting ICD- and pacemaker-related data to the authorized platform; this permits the real-time recording of pacemakers and ICDs and could serve as the basis for more in-depth studies enabling the planning of management, research, and innovation strategies in the Spanish health care system.

CONCLUSIONSThe 2023 Spanish implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry collected information on 96.4% of all implants performed in Spain, which is almost all ICD implants. Even though the total number of implants per million population increased again in 2023 vs previous years and reached a peak, major differences were seen among autonomous communities in ICD implantation rates. In addition, the ICD implantation rate is lower in Spain than in all other European countries, highlighting the need to better identify patients who would benefit from this therapy.

FUNDINGThe registry is partly funded through an agreement between the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices and the Casa del Corazón Foundation. This agreement channels a registered grant established in the 2023 Spanish budget for the management and maintenance of the national pacemaker and implantable defibrillator registries.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSJ. Osca Asensi performed the data analysis, article drafting, and final revision. I. Fernández Lozano and J. Alzueta Rodriguez performed the article drafting and final revision. D. Calvo performed the registry coordination work, data integration, critical revision, and final approval.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank the technical team of the Heart Rhythm Association registries of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Gonzalo Justes, Miguel Salas, Israel García, and Jesús Torre) for their outstanding work in the management and data integration that makes this work possible and the manufacturing and marketing industry for their collaboration.