To the Editor,

Pheochromocytomas are neuroendocrine tumors that are often present in one of the adrenal glands. Among the systemic abnormalities associated with release of catecholamines, cardiac involvement is among the most frequent,1 with reported conditions including transient myocardial dysfunction, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and ventricular arrhythmias.2,3,4

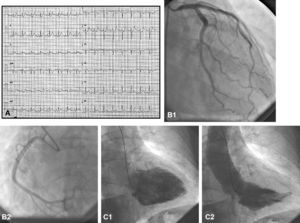

We present the case of a 39-year-old woman with no pertinent history, who was referred to us for primary angioplasty due to inferior ST-elevation ACS (STEACS), defined as angina of 6h duration associated with 2.5mm ST-segment elevation (Figure 1A). Of note in the examination were sinus tachycardia (145beats/min) and arterial hypertension (180/110mmHg). She was treated initially with aspirin and a loading dose of clopidogrel (600mg). During transfer to our hospital, she experienced psychomotor agitation and required sedation. On admission, she was in a stupefied state, with persistent sinus tachycardia, arterial hypertension (systolic blood pressure, 60mmHg) and a lower ST-segment elevation. An emergency coronary angiogram was performed (2000 IU of unfractionated heparin with coadjuvant treatment). This revealed normal coronary arteries (Figure 1B); ventriculography revealed inferior hypokinesis-akinesis with an ejection fraction of 55% (Figure 1C). After the procedure, the patient experienced a deterioration in her state of consciousness and hypoxemia requiring infusion of vasoactive drugs and orotracheal intubation. A computed tomography scan of the brain did not show any intraparenchymal bleeding, although subarachnoid hemorrhage could not be ruled out due to the presence of perimesencephalic contrast. The laboratory tests performed on admission revealed a creatinase level of 1026IU/L (normal range, 25–140IU/L), MB creatinase isoform of 304IU/L (normal range, 0–24IU/L), and troponin T of 8.9ng/mL (normal range, 0–0.1ng/mL). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with marked hemodynamic instability and suffered a cardiorespiratory arrest that did not respond to cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers. She died 2h after admission.

Figure 1. A: ST-segment elevation. B: Normal coronary arteries. C: Inferior hypokinesis-akinesis with ejection fraction of 55%.

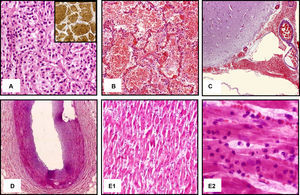

In the autopsy, a pheochromocytoma measuring 3.5cm in diameter was found in the right adrenal gland (Figure 2A). In addition, a massive bilateral pulmonary hemorrhage was observed (Figure 2B) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (Figure 2C). These were identified as the most probable causes of death. The coronary arteries had mild intimal hyperplasia with no luminal occlusion (Figure 2D). Nevertheless, an established acute myocardial infarction (AMI) of between 2 and 12h duration was observed, with involvement of the inferior and posterior walls of the left ventricle (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. A: Hematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemical staining that confirm diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. B: Pulmonary vascular congestion and intra-alveolar hemorrhage. C: Hemorrhage in subarachnoid space. D: Mild intimal coronary hyperplasy. E: Degenerative myocardial changes characteristic of acute myocardial infarction.

In this atypical case resulting in death, the first sign of the hyperadrenergic state was STEACS. Pheochromocytoma crises resembling AMI have been reported.5,6 The abnormalities were explained in terms of severe coronary vasospasm, direct myocardial damage by catecholamines, and increased oxygen uptake as a result of tachycardia and increased afterload. Characteristically, the abnormalities were transient, with normalization after treatment of the tumor. Darzé et al5 reported a similar case, but with no abnormal cardiospecific markers and with total recovery after treatment with α-blockers. Our case had the particular feature of clinical, laboratory, and pathological confirmation of established AMI in a patient with no obstructive lesions in her coronary arteries. The involvement of the inferior and posterior walls in the electrocardiogram, ventriculography findings, and the autopsy point to an unusually prolonged coronary vasospasm in the right coronary artery as the most probable trigger of the events experienced by the patient.

Although the patient was transferred for treatment of ACS, the fatal outcome was related to massive brain and pulmonary hemorrhage, probably as a result of hypertensive crises or direct vascular damage caused by the hyperadrenergic state. In any case, administration of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants as treatment for STEACS may have exacerbated the patient's condition.

In conclusion, the present case highlights one of the characteristics of adrenergic crises. It also points to the wide range of possible presentations that can make an accurate diagnosis so complicated in emergency situations.

Corresponding author: sfcoroleu@hotmail.com