ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) networks should guarantee STEMI care with good clinical results and within the recommended time parameters. There is no contemporary information on the performance of these networks in Spain. The objective of this study was to analyze the clinical characteristics of patients, times to reperfusion, characteristics of the intervention performed, and 30-day mortality.

MethodsProspective, observational, multicenter registry of consecutive patients treated in 17 STEMI networks in Spain (83 centers with the Infarction Code), between April 1 and June 30, 2019.

ResultsA total of 5401 patients were attended (mean age, 64±13 years; 76.9% male), of which 4366 (80.8%) had confirmed STEMI. Of these, 87.5% were treated with primary angioplasty, 4.4% with fibrinolysis, and 8.1% did not receive reperfusion. In patients treated with primary angioplasty, the time between symptom onset and reperfusion was 193 [135-315] minutes and the time between first medical contact and reperfusion was 107 [80-146] minutes. Overall 30-day mortality due to STEMI was 7.9%, while mortality in patients treated with primary angioplasty was 6.8%.

ConclusionsMost patients with STEMI were treated with primary angioplasty. In more than half of the patients, the time from first medical contact to reperfusion was <120 minutes. Mortality at 30 days was relatively low.

Keywords

The superiority of percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) over pharmacological reperfusion therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was clearly established in the early 2000s.1 pPCI is superior to fibrinolysis when performed in a timely manner (within 120minutes of the initial diagnosis) by an experienced team at a specialized hospital. To provide the best reperfusion strategy to as many patients as possible within recommended timeframes, scientific societies recommend the creation of community-wide and regional STEMI networks to expedite the delivery of optimal care.2 In Spain, these systems are known as Infarction Code networks.

Spain's first regional networks were launched in Murcia3 and Navarre4 in 2000. In 2005, Galicia launched PROGALIAM, the country's first multiprovincial program for STEMI care.5 Similar programs were put in place over the following years, and full national coverage was achieved in 2017, with the incorporation of Extremadura, the Canary Islands, and Andalusia.6 From 2004 to 2005, slightly more than one-third of STEMI patients who received reperfusion therapy in Spain were treated with pPCI,7 and this figure increased to just over 54% in 2012.8 The Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) publishes annual activity reports,9 but apart from these and publications by regional networks,3,4,10,11 little is known about the current state of STEMI care within Spain's Infarction Code networks.

To characterize the current situation, 20 years after the creation of Spain's regional STEMI networks, the ACI-SEC Infarction Code Working Group created a registry of consecutive patients with Infarction Code activations over a period of 3 months. The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics of the patients in the registry, the care received, and 30-day outcomes.

METHODSStudy designWe performed an observational study of the prospective, national ACI-SEC Infarction Code Registry, which contains data on patients treated at 83 hospitals within Spain's 17 regional STEMI care networks. We analyzed the clinical characteristics of the patients included, times to reperfusion, treatment characteristics, and 30-day mortality rates. The patients in the registry were treated consecutively over a 3-month period (April 1 to June 30, 2019).

Inclusion criteriaPatients for whom an Infarction Code was activated in any of the regional STEMI care networks and who met the following criteria were included in the study: a) diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment elevation, that is, symptoms compatible with acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment elevation on ECG, a new left bundle branch block, or suspected posterior infarction within 24hours of symptom onset; b) recovery from cardiorespiratory arrest of suspected coronary origin, or c) cardiogenic shock of suspected coronary origin.

Variable definition and collectionThe study variables were entered into a centralized online database and are shown in . All the variables are defined in the study protocol. Each hospital assigned a person to evaluate and add the data to the registry. The ACI-SEC Infarction Code Working Group also appointed a coordinator for each regional network to act as a liaison and clarify doubts. The statistical analyses were performed by the authors of this article.

The timelines from symptom onset to reperfusion were defined according to the European guidelines on STEMI management.2 For each case, the hospitals were asked to provide a subjective opinion on whether there had been an undue delay between the first medical contact and reperfusion (yes/no) and if so, to offer a reason. Code activations were considered inappropriate when, following evaluation on arrival at the pPCI center, the patient did not meet any of the clinical or electrocardiographic (ECG) criteria for STEMI.12 Appropriate activations were classified as clinical false positives when the definitive diagnosis was a condition other than STEMI and as angiographic false positives when no culprit lesion was detected.12 The study protocol was approved by the Infarction Code Working Group and the lead ethics committee. The committee considered it unnecessary to obtain informed consent as the anonymity of the data was guaranteed.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Between-group baseline variables were compared using the t test or chi-square test as appropriate. Times to reperfusion are expressed as median [interquartile range] and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. All statistical analyses were performed in STATA version 15IC (Stata Corp., USA).

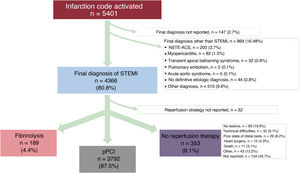

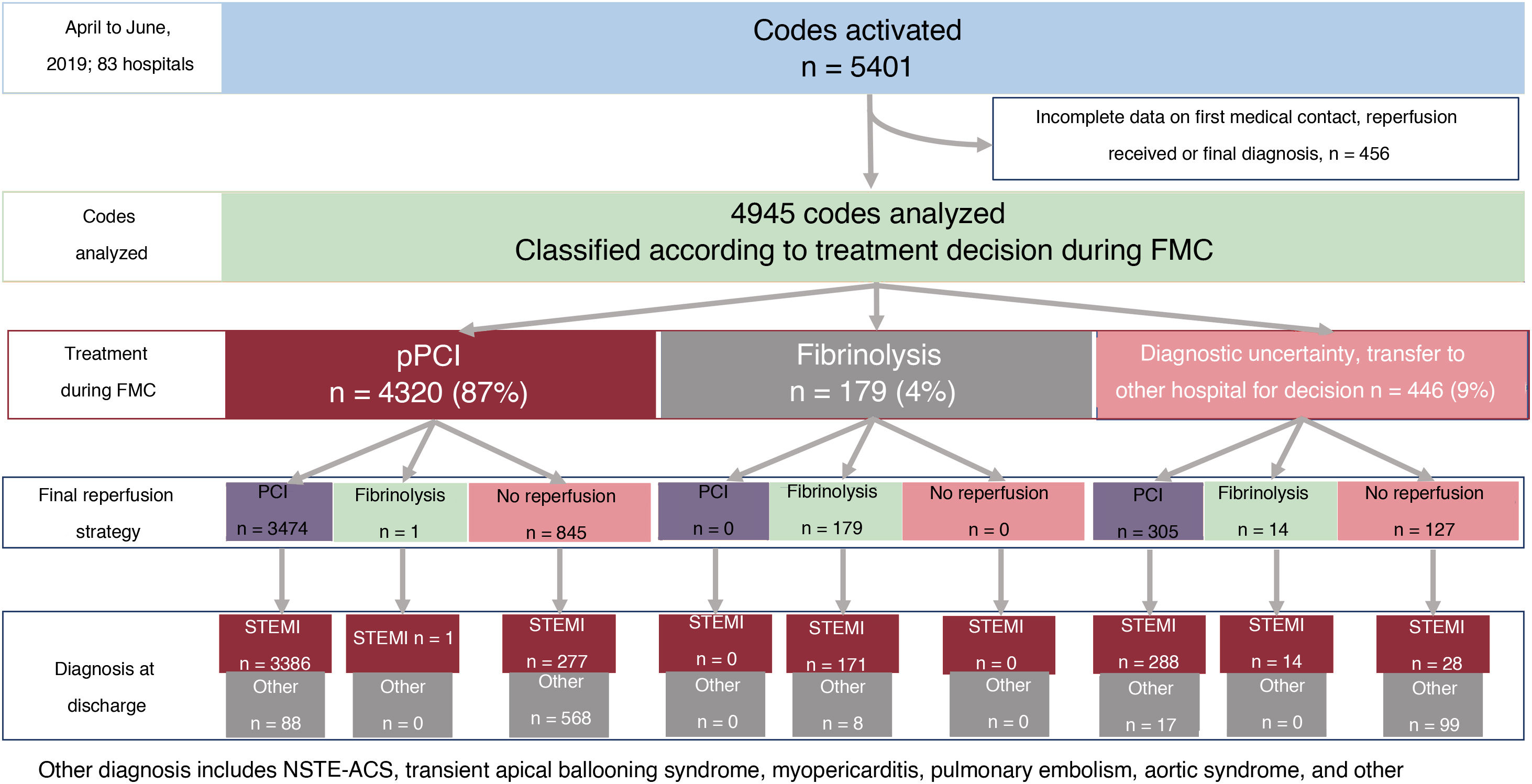

RESULTSInfarction code patientsIn the 3-month study period, 5401 patients were treated within Spain's 17 regional STEMI care networks. The flow of patients according to their final diagnosis is shown in figure 1, together with a breakdown of the reperfusion strategy used in those diagnosed with STEMI (4366 patients, 80.8%). Overall, 3792 patients (87.5%) underwent pPCI, 189 (4.4%) underwent fibrinolysis, and 353 (8.1%) received no reperfusion therapy.

Flowchart showing patients with Spanish Infarction Code activations from April to June 2019 for whom a definitive diagnosis was recorded. Also shown is the reperfusion strategy used in patients diagnosed with STEMI. NSTE-ACS, non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

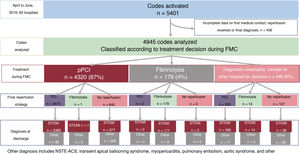

The flow of patients according to treatment decision taken during the first medical contact, treatment administered (pPCI, fibrinolysis, or no reperfusion), and final diagnosis is shown in figure 2.

Flow chart showing patients with Spanish Infarction Code activations from April to June according to treatment decision during FMC, reperfusion strategy applied, and final clinical diagnosis. FMC, first medical contact; NSTE-ACS, non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

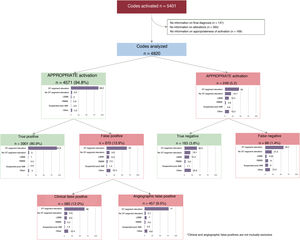

The breakdown of code activations according to appropriateness, final diagnoses, and ECG findings is shown in figure 3. ECG findings and final diagnoses were available for 4820 activations and of these, 4571 (94.8%) were classified as appropriate. There were 3901 true positives for STEMI (80.9%), 580 clinical false positives, and 90 angiographic false positives.

Flowchart showing patients according to appropriateness of code activation together with final clinical diagnosis and electrocardiographic findings in each case. True and false positives were calculated as a percentage of all the codes analyzed. AMI, acute myocardial infarcion; LBBB, left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Code activation was classified as inappropriate in 249 cases; there were 183 true negatives and just 66 false negatives (1.4% of total).

Differential characteristics of patients diagnosed with stemi vs another conditionThe clinical characteristics of patients with a final diagnosis of STEMI vs another condition are summarized in table 1. STEMI was significantly more common in men, smokers, and patients without hypertension or a history of ischemic heart disease, PCI, or heart surgery. Patients diagnosed with a condition other than STEMI were significantly more likely to have ventricular tachycardia and asystole and to need mechanical ventilation during their first medical contact; mortality rates were also higher at this stage.

Clinical characteristics of patients treated within Spain's regional Infarction Code networks according to final diagnosis (STEMI vs other condition)

| STEMI (n=4366) | Not STEMI (n=888) | P | Total (n=5254) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 64±13 | 63±14 | .92 | 64±13 |

| Men | 3403/4365 (78.0) | 642/888 (72.3) | <.0001 | 4045/5253 (76.9) |

| Personal medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 2210/4335 (51.1) | 459/835 (55.6) | .014 | 2669/5160 (51.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1091/4314 (25.3) | 220/824 (26.7) | .40 | 1311/5138 (25.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1961/4326 (45.3) | 371/822 (45.1) | .92 | 2332/5148 (45.3) |

| Active smoking | 1895/4268 (44.4) | 229/819 (28.0) | <.0001 | 2124/5087 (41.8) |

| Previous ischemic heart disease | 452/4318 (10.5) | 122/818 (14.9) | <.0001 | 574/5136 (11.2) |

| Previous PCI | 445/4234 (10.5) | 114/802 (14.2) | .002 | 559/5036 (11.1) |

| Previous heart surgery | 51/4232 (1.2) | 27/804 (3.4) | <.0001 | 78/5036 (1.6) |

| Previous stroke | 176/4222 (4.2) | 39/794 (4.9) | .34 | 215/5016 (4.3) |

| Killip class on admission | ||||

| I | 3462/4248 (81.5) | 565/689 (82.0) | .015 | 4027/4937 (81.6) |

| II | 337/4248 (7.9) | 35/689 (5.1) | 372/4937 (7.5) | |

| III | 129/4248 (3.0) | 30/689 (4.4) | 159/4937 (3.2) | |

| IV | 320/4248 (7.5) | 59/689 (8.6) | 379/4937 (7.7) | |

| First medical contact | ||||

| Out-of-hospital emergency services | 1519/4303 (35.3) | 263/808 (32.6) | <.0001 | 1782/5111 (34.9) |

| Primary care center | 1038/4303 (24.1) | 150/808 (18.6) | 1188/5111 (23.2) | |

| Non-pPCI hospital | 965/4303 (22.4) | 242/808 (30.0) | 1207/5111 (23.6) | |

| pPCI hospital | 781/4303 (18.2) | 153/808 (18.9) | 934/5111 (18.3) | |

| Treatment decision at time of first medical contact | ||||

| pPCI | 3721/4233 (87.9) | 666/797 (83.6) | <.0001 | 4387/5030 (87.2) |

| Fibrinolysis | 173/4233 (4.1) | 8/797 (1.0) | 181/5030 (3.6) | |

| Transfer to non-pPCI hospital for decision | 77/4233 (1.8) | 15/797 (1.9) | 92/5030 (1.8) | |

| Transfer to pPCI hospital for decision | 262/4233 (6.2) | 108/797 (13.6) | 370/5030 (7.4) | |

| Complications during first contact | ||||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 287/4366 (6.6) | 64/888 (7.2) | .49 | 351/5252 (6.7) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 53/4366 (1.2) | 26/888 (2.9) | <.0001 | 79/5254 (1.5) |

| Atrioventricular block | 149/4366 (3.4) | 7/888 (0.8) | <.0001 | 156/5254 (3.0) |

| Asystole | 62/4366 (1.4) | 24/888 (2.7) | .006 | 86/5254 (1.7) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 187/4366 (4.3) | 42/888 (4.7) | .55 | 229/5254 (4.4) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 181/4366 (4.2) | 77/888 (8.7) | <.0001 | 258/5254 (4.9) |

| Death | 9/4366 (0.2) | 6/888 (0.7) | .017 | 15/5254 (0.3) |

| Clinical timelines | ||||

| Time from symptom onset to first medical contact, min | 67 [30-165] | 60 [24.5-180] | <.001 | 65 [30-170] |

| Time from first medical contact to ECG, min | 7 [4-15] | 8 [5-15] | .006 | 7 [4-15] |

| Time from diagnosis to code activation, min | 5 [0-15] | 0 [0-15] | <.001 | 5 [0-15] |

| Time from first medical contact to code activation, min | 15 [6-35] | 24 [10-60] | <.001 | 15 [7-39.5] |

ECG, electrocardiogram; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Not included: 147 patients whose final diagnosis was not reported.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

The clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with STEMI are summarized according to reperfusion strategy in table 2, which also shows the characteristics of the first medical contact and the clinical timelines (from symptom onset to reperfusion).

Clinical and first medical contact characteristics and times from symptom onset to reperfusion in patients with STEMI according to reperfusion strategy

| pPCI (n=3792) | Fibrinolysis (n=189) | No reperfusion (n=353) | pPCI vs fibrinolysis, P | pPCI vs no reperfusion, P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.5±12.9 | 61.5±11.7 | 66.5±14.0 | .032 | <.001 |

| Men | 2971/3792 (78.4) | 159/188 (84.6) | 193/343 (56.3) | .042 | <.001 |

| Personal medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 1910/3773 (50.6) | 94/187 (50.3) | 193/343 (56.3) | .92 | .045 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 948/3754 (25.3) | 40/187 (21.4) | 94/341 (27.6) | .23 | .35 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1699/3764 (45.1) | 93/188 (49.5) | 154/343 (44.9) | .24 | .93 |

| Active smoking | 1677/3716 (45.1) | 97/188 (51.6) | 107/333 (32.1) | .08 | <.001 |

| Previous ischemic heart disease | 380/3761 (10.1) | 19/187 (10.2) | 47/338 (13.9) | .98 | .028 |

| Previous PCI | 386/3681 (10.5) | 14/185 (7.6) | 40/336 (11.9) | .20 | .42 |

| Previous heart surgery | 39/3681 (1.1) | 0/184 (0) | 10/335 (3.0) | .16 | .002 |

| Previous stroke | 150/3673 (4.1) | 7/181 (3.4) | 18/336 (5.4) | .89 | .27 |

| Killip class on admission | |||||

| I | 3064/3724 (82.3) | 136/182 (74.7) | 238/311 (76.5) | .08 | <.001 |

| II | 297/3724 (8.0) | 20/182 (11.0) | 19/311 (6.1) | ||

| III | 108/3724 (2.9) | 8/182 (4.4) | 10/311 (3.2) | ||

| IV | 255/3724 (6.9) | 18/182 (9.9) | 44/311 (14.2) | ||

| First medical contact | |||||

| Out-of-hospital emergency services | 1338/3754 (35.6) | 50/187 (26.7) | 119/330 (36.1) | <.001 | .89 |

| Primary care center | 912/3754 (24.3) | 49/187 (26.2) | 75/330 (22.7) | ||

| Non-pPCI hospital | 799/3754 (21.3) | 77/187 (41.2) | 75/330 (22.7) | ||

| pPCI hospital | 705/3754 (18.8) | 11/187 (5.9) | 61/330 (18.5) | ||

| Treatment decision at time of first medical contact | |||||

| pPCI | 3416/3707 (92.2) | 1/188 (0.5) | 279/307 (90.9) | <.001 | .67 |

| Fibrinolysis | 0/3707 (0) | 173/188 (92.0) | 0/307 (0) | ||

| Transfer to non-pPCI hospital for decision | 61/3707 (1.7) | 10/188 (5.3) | 5/307 (1.6) | ||

| Transfer to pPCI hospital for decision | 230/3707 (6.2) | 4/188 (2.1) | 23/307 (7.5) | ||

| Complications during first contact | |||||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 242/3792 (6.4) | 24/189 (12.8) | 21/353 (6.0) | .001 | .75 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 42/3792 (1.1) | 5/189 (2.7) | 6/353 (1.7) | .056 | .32 |

| Atrioventricular block | 132/3792 (3.5) | 7/189 (3.7) | 10/353 (2.8) | .87 | .52 |

| Asystole | 46/3792 (1.2) | 4/189 (2.1) | 12/353 (3.4) | .28 | .001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 144/3792 (3.8) | 12/189 (6.3) | 29/353 (8.2) | .08 | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 147/3792 (3.9) | 15/189 (7.9) | 19/353 (5.4) | .006 | .17 |

| Death | 1/3792 (0.0) | 2/187 (1.1) | 6/353 (1.7) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Clinical timelines | |||||

| Time from symptom onset to first medical contact, min | 66 [30-165] | 60 [30-120] | 75 [30-210] | .016 | .17 |

| Time from first medical contact to ECG, min | 7 [4-15] | 6 [3.5-15] | 8 [4-13] | .13 | .72 |

| Time from diagnosis to code activation, min | 5 [0-15] | 9 [0-30] | 5 [0-18] | .001 | .47 |

| Time from first medical contact to code activation, min | 15 [6-35] | 10 [5-25] | 15 [8-41] | <.001 | .29 |

| Time from symptom onset to reperfusion, min | 193 [135-315] | 120 [75-195] | - | <.001 | - |

| Time from first medical contact to reperfusion, min | 107 [80-146] | 36.5 [20-68] | - | <.001 | - |

ECG, electrocardiogram; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Not included: 32 patients without specification of reperfusion strategy.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

Compared with patients who underwent pPCI, those treated with fibrinolysis (n=189) were younger, more likely to be men, and less likely to be treated at a specialized pPCI hospital. They were also more likely to have ventricular fibrillation and to die during the first medical contact. They had a shorter time from symptom onset to first medical contract. Median time from first medical contact to initiation of fibrinolysis was 36.5 [IQR, 20-68] minutes. Overall, 106 patients (56.1%) treated with fibrinolysis underwent rescue PCI, while 74 (39.2%) underwent deferred revascularization of the culprit lesion. Coronary angiography without revascularization was performed in 7 patients (3.7%); 2 patients (1.1%) did not undergo angiography as they died during the first medical contact. Reasons for performing fibrinolysis rather than pPCI were an estimated time to pPCI of >120minutes in 64% of patients and unavailability of pPCI in 19%. Other reasons were given for 17.3% of patients.

Compared with patients treated with pPCI, those who did not receive reperfusion therapy were older and more likely to be women, have pre-existing heart failure, and present with asystole or cardiogenic shock or die during the first medical contact.

Angiographic and procedure-related characteristics of patients treated with ppciAngiographic and procedure-related characteristics for STEMI patients treated with pPCI are shown in table 3. Radial access was used in >90% of cases; 63% of patients had single-vessel disease, while 28% required mechanical thrombectomy. The mean number of stents implanted was 1.30±0.72 per patient; bare-metal stents were used in just 7% of cases. Plain angioplasty or thrombectomy was used in 4.4% of revascularized patients who did not receive a stent. PCI was used to treat a nonculprit artery during pPCI in 6.8% of patients. Although 7.5% of patients presented with cardiogenic shock, a hemodynamic support device (mainly an intra-aortic balloon pump) was used in just 2.4% of cases. Most patients were treated with aspirin (97.6%) and P2Y12 receptor inhibitors (95.1%). Ticagrelor was the most widely used inhibitor (52.5%).

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention characteristics in STEMI patients

| Radial access | 3302/3659 (90.2) |

| Baseline TIMI flow | |

| 0 | 2697/3687 (73.2) |

| 1 | 295/3687 (8.0) |

| 2 | 330/3687 (8.9) |

| 3 | 365/3687 (9.9) |

| Final TIMI flow | |

| 0 | 37/3722 (1.0) |

| 1 | 22/3722 (0.9) |

| 2 | 129/3722 (3.5) |

| 3 | 3523/3722 (94.7) |

| Antiplatelet treatment | |

| Aspirin | 2947/3020 (97.6) |

| Clopidogrel | 1000/3019 (33.1) |

| Ticagrelor | 1586/3019 (52.5) |

| Prasugrel | 286/3019 (9.5) |

| Culprit vessel | |

| Left truncus arteriosus | 57/3693 (1.5) |

| Anterior descending artery | 1615/3693 (43.7) |

| Circumflex artery | 586/3693 (15.9) |

| Right coronary artery | 1421/3693 (38.5) |

| Graft | 14/3693 (0.4) |

| Diseased vessels, No | |

| 1 | 2358/3728 (63.3) |

| 2 | 909/3728 (24.4) |

| 3 | 461/3728 (12.4) |

| Hemodynamic support devices | |

| None | 3701/3792 (97.6) |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 56/3792 (1.5) |

| Impella | 9/3792 (0.2) |

| ECMO | 4/3792 (0.1) |

| Other | 22/3792 (0.6) |

| Type of intervention | |

| Mechanical thrombectomy | 1084/3792 (28.6) |

| Balloon dilation | 1647/3792 (43.4) |

| Metal stent implantation | 262/3792 (6.9) |

| Drug-eluting stent implantation | 3365/3792 (88.7) |

| Stents implanted per patient, No. | 1.30±0.72 |

| Intervention on nonculprit vessel | 241/3.536 (6.8) |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

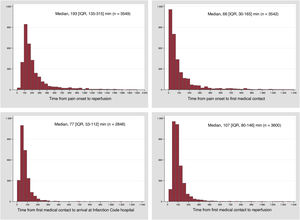

The timelines from symptom onset to reperfusion in STEMI patients treated with pPCI are shown in figure 4. The median times calculated were 66 [IQR, 30-165] minutes for symptom onset to first medical contact, 107 [IQR, 80-146] minutes for first medical contact to reperfusion, and 193 [IQR, 135-315] minutes for symptom onset to reperfusion. A time of <120minutes from first contact to reperfusion was observed in 71.4% of patients treated by emergency medical services, 48.6% of patients treated at a non-pPCI hospital, and 74.3% of patients treated at a pPCI hospital.

Time from symptom onset to first medical contact in patients treated with fibrinolysis was 60 [IQR, 30-120] minutes. The other times were 36.5 [IQR, 20-68] minutes for first medical contact to initiation of fibrinolysis and 120 [IQR, 75-195] minutes for symptom onset to initiation of fibrinolysis. Median time from fibrinolytic administration to revascularization in the 106 patients who required rescue PCI was 165 [130-255] minutes. Coronary angiography was performed within 24hours in 86.4% of the 81 patients who underwent this procedure after effective fibrinolysis.

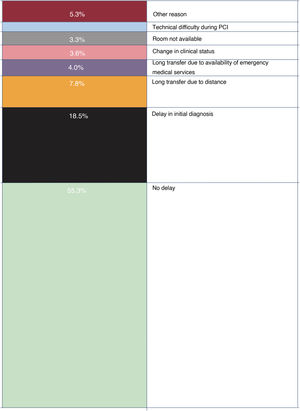

An undue delay from first medical contact to reperfusion (>120minutes) was reported for 44.7% of patients. The main reason given (in 18.5% of cases) was a delay in the initial diagnosis (figure 5). Time from first medical contact to ECG was >10minutes in 30.8% of patients.

Reasons for undue delays between first medical contact and reperfusion. Observation of an undue delay between the first medical contact and reperfusion did not necessarily mean that reperfusion was not performed within the recommended 120minutes. In fact, reperfusion was performed within 120minutes of the first medical contact in 53.2% of cases, but 21.5% of these were considered to involve an undue delay. PCI, primary cutaneous intervention.

Complications during first medical contact, cardiac catheterization, and subsequent hospitalization are shown in table 4.

Complications during first medical contact, cardiac catheterization, and subsequent hospitalization

| STEMI (n=4366) | Not STEMI (n=888) | P | Total (n=5254) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications during first contact | ||||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 287/4366 (6.6) | 64/888 (7.2) | .49 | 351/5252 (6.7) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 53/4366 (1.2) | 26/888 (2.9) | <.0001 | 79/5254 (1.5) |

| Atrioventricular block | 149/4366 (3.4) | 7/888 (0.8) | <.0001 | 156/5254 (3.0) |

| Asystole | 62/4366 (1.4) | 24/888 (2.7) | .006 | 86/5254 (1.7) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 187/4366 (4.3) | 42/888 (4.7) | .55 | 229/5254 (4.4) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 181/4366 (4.2) | 77/888 (8.7) | <.0001 | 258/5254 (4.9) |

| Death | 9/4366 (0.2) | 6/888 (0.7) | .017 | 15/5254 (0.3) |

| Complications during cardiac catheterization | ||||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 87/4366 (2.0) | 5/888 (0.6) | .003 | 92/5254 (1.8) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 45/4366 (1.0) | 6/888 (0.7) | .33 | 51/5254 (1.0) |

| Atrioventricular block | 94/4366 (2.2) | 3/888 (0.3) | <.0001 | 97/5254 (1.9) |

| Asystole | 26/4366 (0.6) | 6/888 (0.7) | .78 | 32/5254 (0.6) |

| Acute pulmonary edema | 50/4366 (1.2) | 5/888 (0.6) | .12 | 55/5254 (1.1) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 158/4366 (3.6) | 22/888 (2.5) | .088 | 180/5251 (3.4) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 67/4366 (1.5) | 13/888 (1.5) | .88 | 80/5254 (1.5) |

| Death | 41/4366 (0.9) | 7/888 (0.8) | .67 | 48/5254 (0.9) |

| Complications during hospitalization | ||||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 86/4366 (2.0) | 12/888 (1.4) | .21 | 98/5254 (1.9) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 75/4366 (1.6) | 11/888 (1.2) | .31 | 86/5254 (1.6) |

| Atrioventricular block | 77/4366 (1.6) | 7/888 (0.8) | .035 | 84/5254 (1.6) |

| Asystole | 38/4366 (0.9) | 12/888 (1.4) | .18 | 50/5254 (1.0) |

| Acute pulmonary edema | 98/4366 (2.2) | 27/888 (3.0) | .16 | 125/5254 (2.4) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 247/4366 (5.7) | 45/888 (5.1) | .48 | 292/5254 (5.6) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 123/4366 (2.8) | 31/888 (3.5) | .29 | 154/5254 (2.9) |

| Stent thrombosis | 46/4366 (1.1) | 0/888 (0) | .002 | 46/5254 (0.9) |

| Reinfarction | 31/4366 (0.7) | 0/888 (0) | .012 | 31/5254 (0.6) |

| Mechanical complication | 26/4263 (0.6) | 2/862 (0.2) | .2 | 28/5125 (0.6) |

| Hemorrhage | 39/4366 (0.9) | 2/888 (0.2) | .039 | 41/5254 (0.8) |

STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

In-hospital and 30-day mortality rates are shown in figure 4. Mortality was lower in patients diagnosed with STEMI than in those diagnosed with another condition (5.5% vs 7.3% for in-hospital mortality [P=.032] and 7.9% vs 10.7% for 30-day mortality [P=.009]). Respective rates according to the reperfusion strategy employed in the STEMI group were 4.8% and 6.8% for pPCI and 6.4% and 9.6% for fibrinolysis. Mortality was significantly higher in patients who not receiving reperfusion: 12.4% for in-hospital mortality and 18.2% for 30-day mortality (figure 6).

DISCUSSIONWe have characterized the current situation of STEMI care within Spain's regional Infarction Code networks. The most noteworthy findings are that a) >80% of patients received a final diagnosis of STEMI, and, of these, >87% were treated with pPCI (<5% underwent fibrinolysis and just over 8% did not receive reperfusion therapy); b) median time to reperfusion in the pPCI group was 193minutes from symptom onset and 107minutes from first medical contact; c) the main reason given for undue delays between first medical contact and reperfusion was a delay in the initial diagnosis; and d) 30-day mortality rates were 7.9% for patients with STEMI and 6.8% for those treated with pPCI.

The Spanish public health care system has 17 regional STEMI care networks comprising 83 hospitals that provide interrupted pPCI services 365 days a year. According to the ACI-SEC activity report for 2019, 22 529 PCIs were performed in patients with myocardial infarction; of these, 91.8% were primary procedures, 2.5% were rescue procedures after failed fibrinolysis, and 5.7% were deferred or scheduled procedures.9 These figures are consistent with the rates observed in the current registry.

Spain's regional Infarction Code networks have provided nationwide coverage since 2017,6 resulting in improved treatment for patients with STEMI. According to data from the MASCARA study,7 just 37% of STEMI patients who received reperfusion therapy from 2004 to 2005 were treated with pPCI, compared with 54% in 201213 and 95.3% in the current registry. Reperfusion rates have also increased significantly. Just 8% of patients in our series, for example, did not receive reperfusion therapy compared with 36% of patients in 2012.13 These improvements have been accompanied by a sizeable decrease in in-hospital mortality rates (from 9.2% in 201213 to 5.5% in our registry).

The inappropriate code activation rate observed in our study is similar to rates reported elsewhere, which can range from 5% to 31%, depending on the definition.14 In Spain, data from the Catalan Infarction Code network for 2010 to 2011 showed an inappropriate activation rate of 12.2%, an angiographic false positive rate of 14.6%, and a clinical false positive rate of 11.6%.15 These rates are similar to those observed in the current study. Conditions finally diagnosed as something other than STEMI were the cause of greater diagnostic uncertainty during the first medical contact, with patients more likely to be transferred to a pPCI hospital for diagnostic confirmation and treatment decision. More than 50% of patients with an inappropriate code activation did not have ST-segment elevation on ECG. Defining an ideal inappropriate activation rate is difficult, as an excessively high rate would result in considerable overuse of resources, while an excessively low rate would mean that not all STEMI patients would receive the treatment they needed. Training for the health care professionals involved in the diagnosis of STEMI is crucial,16 particularly considering that the main reason given for excessive time to reperfusion in our series was a delay in the initial diagnosis.

Median time from first medical contact to reperfusion by pPCI was 107minutes; this is in line with the European guideline recommendation for the management of acute STEMI2 and shorter than times reported for other countries in Europe.17 Nonetheless, the hospitals analyzed reported an undue delay in 45% of cases, although these delays did not necessarily mean reperfusion was not performed within the recommended 120minutes from first medical contact. The above results would appear to indicate the achievement of considerable improvements. Further improvements could be achieved by local monitoring of times to reperfusion to detect excessive delays and areas for improvement.18,19 Expeditious reperfusion care is critical, as reductions in delays have been linked to lower adverse cardiovascular outcome rates.20

Radial access for PCI has been associated with lower morbidity and mortality in STEMI21,22 and clearly emerged as the route of choice in Spain, being used in >90% of pPCIs. Mechanical thrombectomy was used in >28% of patients. Based on the results of the TOTAL trial,23 European guidelines advise against routine thrombectomy, while recognizing its potential benefits in patients with a high thrombus burden.2 We unfortunately did not have access to data on lesion characteristics to determine the presence of abundant thrombus material in the cases treated by thrombectomy in our series, but the rate observed would appear to be in keeping with the guideline recommendation. Use of stents was also in line with guideline recommendations, as drug-eluting stents were used in almost 89% of cases and bare-metal stents in just 7%.

The data from the ACI-SEC Infarction Code registry should shed light on current deficiencies in clinical practice and help evaluate the quality of STEMI care in Spain. Although the creation of the Spanish Infarction Code networks was an arduous journey during which economic and structural shortcomings were often compensated by the dedication and commitment of those at the frontline of care,24 the improved clinical outcomes have made the efforts worthwhile. Apart from ensuring the continued functioning of these complex programs, it is now crucial to provide the different network components with the necessary funding to ensure their long-term sustainability.6

LimitationsThis study has a number of limitations inherent to any multicenter observational study. Inaccuracies and misclassification, for example, can occur when data are collected and evaluated by individual centers, without centralized monitoring. Interventional cardiology data, however, are quite well standardized around the world and the online data entry form was designed to be intuitive and universally applicable. It should also be noted that STEMI patients treated outside the Infarction Code networks are not included in the registry, although the selection bias introduced is probably minimal due to their small number. Patients with subacute myocardial infarction who did not meet the criteria for emergent reperfusion were also not included. Although the data from the registry are from 2019, there have been no major organizational changes that would have affected the functioning of the networks in the last 2 years, or any significant changes to the European STEMI guidelines (published in 2017). In addition, a study conducted during the first wave of the coronavirus 2019 pandemic did not detect any changes to reperfusion strategies or time from first medical contact to reperfusion, although it did find an increase in STEMI-associated mortality, partly attributable to longer ischemia times.25

CONCLUSIONSThis analysis of the ACI-SEC Infarction Code registry shows the current state of STEMI care within Spain's regional networks. Overall, >80% of patients received a definitive diagnosis of STEMI, and the vast majority received reperfusion therapy, in most cases by pPCI. Time from first medical contact to reperfusion was <120 minutes in >50% of cases. In-hospital and 30-day mortality rates have improved significantly since the national implementation of Spain's Infarction Code networks. The participating hospitals, however, reported undue delays in almost 50% of patients, with most cases being attributed to a delay in the initial diagnosis. The different agents involved in these networks should take the necessary steps to expedite reperfusion care.

- –

pPCI is the treatment of choice in STEMI when performed by an experienced team within recommended timeframes, and where possible, within coordinated care systems.

- –

Spain's first regional Infarction Code networks were implemented in 2000 and the journey to achieve nationwide coverage was completed in 2017.

- –

Little has been published on clinical STEMI outcomes since the nationwide implementation of the networks.

- –

Most STEMI patients analyzed received reperfusion therapy, mostly by pPCI; time from first medical contact to reperfusion was <120minutes in >50% of cases.

- –

Mortality rates have improved significantly since the widespread implementation of the Infarction Code networks.

- –

Undue delays, mostly attributable to a delay in the initial diagnosis, were detected in almost 50% of patients.

No funding was received.

Authors’ CONTRIBUTIONSWriting of manuscript: O. Rodríguez-Leor, A.B. Cid-Álvarez, and A. Pérez de Prado. Revision of manuscript: all authors. Statistical analysis: O. Rodríguez-Leor and X. Rosselló. Revision of database: O. Rodríguez-Leor, A.B. Cid-Álvarez, and A. Pérez de Prado. Coordination of regional Infarction Code networks: all authors.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTA. Pérez de Prado has received personal funding from iVascular, Boston Scientific, Terumo, Bbraun, and Abbott Vascular; Á. Cequier has received personal funding from Ferrer International, Terumo, Astra Zeneca, and Biotronik. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to the content of this article.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2021.12.005