To evaluate the prevalence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of patients with angina undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for severe aortic stenosis.

MethodsA total of 1687 consecutive patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR at our center were included and classified according to patient-reported angina symptoms prior to the TAVR procedure. Baseline, procedural and follow-up data were collected in a dedicated database.

ResultsA total of 497 patients (29%) had angina prior to the TAVR procedure. Patients with angina at baseline showed a worse New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (NYHA class> II: 69% vs 63%; P=.017), a higher rate of coronary artery disease (74% vs 56%; P <.001), and a lower rate of complete revascularization (70% vs 79%; P <.001). Angina at baseline had no impact on all-cause mortality (HR, 1.02; 95%CI, 0.71-1.48; P=.898) and cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.2; 95%CI, 0.69-2.11; P=.517) at 1 year. However, persistent angina at 30 days post-TAVR was associated with increased all-cause mortality (HR, 4.86; 95%CI, 1.71-13.8; P=.003) and cardiovascular mortality (HR, 20.7; 95%CI, 3.50-122.6; P=.001) at 1-year follow-up.

ConclusionsMore than one-fourth of patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR had angina prior to the procedure. Angina at baseline did not appear to be a sign of a more advanced valvular disease and had no prognostic impact; however, persistent angina at 30 days post-TAVR was associated with worse clinical outcomes.

Keywords

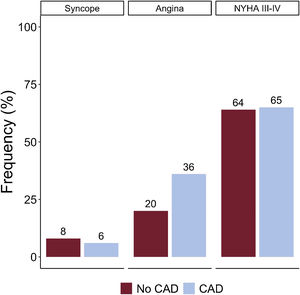

Aortic valve stenosis is known to be the most common valvular heart disease in the western world.1 In 1968, Ross and Braunwald famously described angina, dyspnea, and syncope as the 3 cardinal symptoms of aortic stenosis and pointed out the unfavorable prognosis associated with the onset of these symptoms.2 The dogma regarding symptom onset and its association with a dismal prognosis remains valid. Hence, the current guidelines still recommend “watchful waiting” in most asymptomatic patients with severe AS.3,4 While syncope is traditionally ascribed to the incapacity to adequately increase cardiac output in the presence of increased peripheral demand, and dyspnea seems mainly to be driven by the increased filling pressures, angina is generally understood as a mismatch between myocardial oxygen demand and oxygen supply, either due to the aortic stenosis itself or to coexisting significant coronary artery disease (CAD).5,6

Degenerative aortic valve stenosis and CAD share some etiological factors and often coexist.7 In randomized trials, CAD was found in> 60% of intermediate-risk patients with severe AS.8,9 Angina is a common symptom both in CAD and in severe AS, occurring in up to two-thirds of patients with severe AS.10

In the surgical population, the prevalence of coexisting CAD and the predictive value of angina to detect CAD in patients with severe AS has been examined in previous publications.11–13 However, little is known about the prevalence and significance of angina in the TAVR population. The aim of this study was therefore to analyze the prevalence, clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with angina undergoing TAVR for severe AS.

METHODSStudy populationWe analyzed 1910 consecutive patients with severe AS undergoing TAVR in a tertiary university center between 2007 and 2021. Of these, we excluded 223 patients with missing or uncertain data on the angina symptoms associated with AS prior to the TAVR procedure, leading to a final study population of 1687 patients. The indications for TAVR, device type and procedural approach were assessed by the Heart Team, based on an extensive preoperative clinical and anatomical assessment. The transfemoral approach was used by default, and alternative accesses including transcarotid, transapical, transsubclavian, and transaortic were reserved for patients with unfavorable peripheral anatomy. The selection of the secondary arterial access (transfemoral or transradial) was left to operators’ discretion.

Patients were classified according to the presence of angina prior to the TAVR procedure. The classification was based on patient-reported angina symptoms at the time of referral and pre-TAVR evaluation (no further categorization of angina symptoms according to any angina grading system).

Data were collected prospectively in a dedicated database including baseline variables, procedure-related variables and prospective follow-up data to assess short- and long-term clinical events and survival. Clinical follow-up was conducted through clinical visits and/or telephone contact at 1 month, 12 months, and yearly thereafter. Clinical events were defined according to Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 criteria.14 The collection and recording of patients’ information were approved by the local ethics committee, and the patients provided signed informed consent for the procedures, anonymous data collection, and reporting.

Coronary artery disease assessmentAs part of the routine pre-TAVR work-up, all patients underwent coronary angiography before TAVR. The results of coronary angiography were extracted from the medical report, including the number and location of any significant lesions. Significant CAD was defined as ≥ 70% stenosis in an epicardial coronary artery (≥ 50% for left main) by angiographic assessment, or status after coronary revascularization. Significant lesions suitable for revascularization were systematically treated independently of patient's symptoms. Revascularization was considered complete if all significant lesions in vessels of ≥ 2mm in diameter had been successfully treated with either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The treatment strategy, including the decision about the completeness of revascularization, was decided according to the local Heart Team consensus.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation or median [Q1-Q3] according to the normality of data distribution assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (%). The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare the categorical variables and the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous variables. For 1-year survival analysis, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain event curves. The difference between the probability of event occurrence was assessed with the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of angina on patient survival. Models were adjusted for baseline confounders based on prior causal knowledge. P <.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests. All data were analyzed using the statistical package STATA version 15.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, United States).

RESULTSAmong 1687 patients undergoing TAVR for AS, a total of 497 patients (29%) had angina prior to the TAVR procedure. Figure 1 displays the distribution of the 3 cardinal symptoms (angina, dyspnea, and syncope) in AS in patients with and without coexisting CAD.

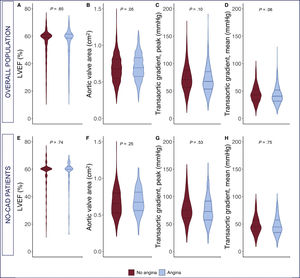

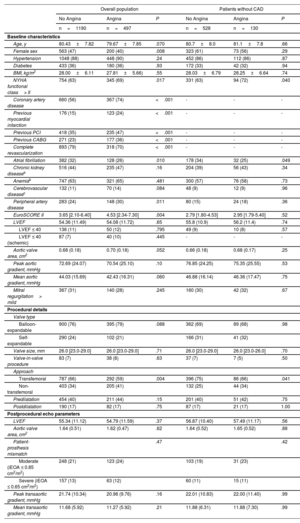

The baseline and procedural characteristics, according to the presence of angina for the overall population as well as for the subgroup without CAD, are shown in table 1. Patients with angina were more commonly men (60% vs 53%, P=.008), tended to be younger (79.7±7.9 years vs 80.4±7.8 years, P=.07), and had a worse New York Heart Association functional class (NYHA class> II: 69% vs 63%, P=.017), a higher rate of CAD (74% vs 56%, P <.001), a higher rate of previous revascularization (previous PCI, 47% vs 35%, P <.001; previous CABG: 36% vs 23%, P <.001), and a lower rate of complete revascularization (70% vs 79%, P <.001). A comparison of the echocardiographic baseline parameter of patients with and without angina is shown in figure 2. Except for a tendency toward a lower mean gradient and greater aortic valve area in patients with angina at baseline, there were no differences between groups in echocardiographic baseline parameters. No differences were found in procedural characteristics except for an increased rate of nontransfemoral access (41% vs 34%, P=.004) among angina patients. The results of the TAVR procedure, evaluated by Doppler echocardiography post-TAVR, were also similar between groups.

Baseline and procedural characteristics in the overall population and in patients without CAD

| Overall population | Patients without CAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Angina | Angina | P | No Angina | Angina | P | |

| n=1190 | n=497 | n=528 | n=130 | |||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | 80.43±7.82 | 79.67±7.85 | .070 | 80.7±8.0 | 81.1±7.8 | .66 |

| Female sex | 563 (47) | 200 (40) | .008 | 323 (61) | 73 (56) | .29 |

| Hypertension | 1048 (88) | 448 (90) | .24 | 452 (86) | 112 (86) | .87 |

| Diabetes | 433 (36) | 180 (36) | .93 | 172 (33) | 42 (32) | .94 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.00±6.11 | 27.81±5.66) | .55 | 28.03±6.79 | 28.25±6.64 | .74 |

| NYHA functional class> II | 754 (63) | 345 (69) | .017 | 331 (63) | 94 (72) | .040 |

| Coronary artery disease | 660 (56) | 367 (74) | <.001 | - | - | - |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 176 (15) | 123 (24) | <.001 | - | - | - |

| Previous PCI | 418 (35) | 235 (47) | <.001 | - | - | - |

| Previous CABG | 271 (23) | 177 (36) | <.001 | - | - | - |

| Complete revascularization | 893 (79) | 318 (70) | <.001 | - | - | - |

| Atrial fibrillation | 382 (32) | 128 (26) | .010 | 178 (34) | 32 (25) | .049 |

| Chronic kidney diseasea | 516 (44) | 235 (47) | .16 | 204 (39) | 56 (43) | .34 |

| Anemiab | 747 (63) | 321 (65) | .481 | 300 (57) | 76 (58) | .73 |

| Cerebrovascular diseasec | 132 (11) | 70 (14) | .084 | 48 (9) | 12 (9) | .96 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 283 (24) | 148 (30) | .011 | 80 (15) | 24 (18) | .36 |

| EuroSCORE II | 3.65 [2.10-6.40] | 4.53 [2.34-7.30] | .004 | 2.79 [1.80-4.53] | 2.95 [1.79-5.40] | .52 |

| LVEF | 54.36 (11.49) | 54.08 (11.72) | .65 | 55.8 (10.9) | 56.2 (11.4) | .74 |

| LVEF ≤ 40 | 136 (11) | 50 (12) | .795 | 49 (9) | 10 (8) | .57 |

| LVEF ≤ 40 (ischemic) | 87 (7) | 40 (10) | .445 | - | - | - |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.70 (0.18) | .052 | 0.66 (0.18) | 0.68 (0.17) | .25 |

| Peak aortic gradient, mmHg | 72.69 (24.07) | 70.54 (25.10) | .10 | 76.85 (24.25) | 75.35 (25.55) | .53 |

| Mean aortic gradient, mmHg | 44.03 (15.69) | 42.43 (16.31) | .060 | 46.88 (16.14) | 46.36 (17.47) | .75 |

| Mitral regurgitation> mild | 367 (31) | 140 (28) | .245 | 160 (30) | 42 (32) | .67 |

| Procedural details | ||||||

| Valve type | ||||||

| Balloon-expandable | 900 (76) | 395 (79) | .088 | 362 (69) | 89 (68) | .98 |

| Self-expandable | 290 (24) | 102 (21) | 166 (31) | 41 (32) | ||

| Valve size, mm | 26.0 [23.0-29.0] | 26.0 [23.0-29.0] | .71 | 26.0 [23.0-29.0] | 26.0 [23.0-26.0] | .70 |

| Valve-in-valve procedure | 83 (7) | 38 (8) | .63 | 37 (7) | 7 (5) | .50 |

| Approach | ||||||

| Transfemoral | 787 (66) | 292 (59) | .004 | 396 (75) | 86 (66) | .041 |

| Non-transfemoral | 403 (34) | 205 (41) | 132 (25) | 44 (34) | ||

| Predilatation | 454 (40) | 211 (44) | .15 | 201 (40) | 51 (42) | .75 |

| Postdilatation | 190 (17) | 82 (17) | .75 | 87 (17) | 21 (17) | 1.00 |

| Postprocedural echo parameters | ||||||

| LVEF | 55.34 (11.12) | 54.79 (11.59) | .37 | 56.87 (10.40) | 57.49 (11.17) | .56 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 1.64 (0.51) | 1.62 (0.47) | .62 | 1.64 (0.52) | 1.65 (0.52) | .88 |

| Patient-prosthesis mismatch | .47 | .42 | ||||

| Moderate (iEOA ≤ 0.85 cm2/m2) | 248 (21) | 123 (24) | 103 (19) | 31 (23) | ||

| Severe (iEOA ≤ 0.65 cm2/m2) | 157 (13) | 63 (12) | 60 (11) | 15 (11) | ||

| Peak transaortic gradient, mmHg | 21.74 (10.34) | 20.96 (9.76) | .16 | 22.01 (10.83) | 22.00 (11.40) | .99 |

| Mean transaortic gradient, mmHg | 11.68 (5.92) | 11.27 (5.92) | .21 | 11.88 (6.31) | 11.88 (7.30) | .99 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; iEOA, indexed effective orifice area; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Values are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

Comparison of baseline echocardiographic parameters in patients with and without angina in the overall population (upper panel) and in patients without coexisting CAD (lower panel). A: left ventricular ejection fraction; B: aortic valve area; C: transaortic peak gradient; D: transaortic mean gradient. CAD, coronary artery disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Among the 658 patients without coexisting CAD, 130 patients (20%) with angina at baseline were identified. The subgroup analysis showed no significant differences in baseline variables between patients with and without angina, except for a lower rate of atrial fibrillation (25% vs 34%, P=.049) and a worse NYHA functional class (NYHA class> II: 72% vs 63%, P=.04) in the angina group. There were no differences in baseline echocardiographic parameters between the groups (angina vs no angina) in patients without CAD (table 1).

During the pre-TAVR work-up (including routine coronary angiography), a PCI was performed in 22% of patients, with no differences in the rate of PCI in patients with and without angina at baseline (23% vs 21%; P=.39). Complete revascularization during TAVR work-up was more common (nonsignificant trend) among patients without angina (75% vs 66%, P=.062). Detailed information on the pre-TAVR coronary angiography findings and PCI in patients with and without angina is shown in .

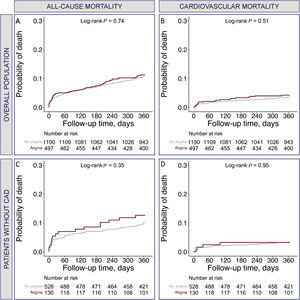

Prognostic significance of angina at baselineThe 1-year clinical outcomes according to the presence of angina for the overall population and the subgroup without CAD are shown in table 2. Angina at baseline had no impact on all-cause mortality (HR, 1.02; 95%CI, 0.71-1.48; P=.898) or cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.2; 95%CI, 0.69-2.11; P=.517) at 1 year. The subgroup analysis in patients without coexisting CAD showed no impact of angina on all-cause mortality (HR, 1.18; 95%CI, 0.64-2.27; P=.598) and cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.04; 95%CI, 0.35-3.12; P=.545) at 1 year. The Kaplan-Meier curves at 1-year follow-up regarding all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality post-TAVR, according to the presence of angina for the overall population and the subgroup without CAD, are shown in figure 3.

Comparison of event occurrence and risk for events at 1 year between patients with and without angina

| Overall population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total(N=1687) | No angina(n=1190) | Angina(n=497) | P | HR(95%CI) | P | |

| All-cause mortalitya | 180(11) | 125(11) | 55(11) | .733 | 1.02(0.71-1.48) | .898 |

| Cardiovascular mortalitya | 60(4) | 40(3) | 20(4) | .503 | 1.20(0.69-2.11) | .517 |

| Acute coronary syndromeb | 29(2) | 13(1) | 16(3) | .002 | 2.10(0.97-4.53) | .058 |

| Heart failure hospitalizationc | 135(8) | 99(8) | 36(7) | .458 | 0.83(0.56-1.22) | .331 |

| Patients without CAD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total(n=658) | No angina(n=528) | Angina(n=130) | P | HR (95CI) | P | |

| All-cause mortalitya | 68(10) | 52(10) | 16(12) | .409 | 1.18(0.64-2.27) | .598 |

| Cardiovascular mortalitya | 21(3) | 4(3) | 17(3) | .934 | 1.04(0.35-3.12) | .545 |

| Acute coronary syndromeb | 3(<1) | 1(<1) | 2(2) | .041 | 9.10(0.82-100.57) | .072 |

| Heart failure hospitalizationc | 46(7) | 38(7) | 8(6) | .676 | 0.84(0.58-1-24) | .398 |

CAD, coronary artery disease, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The data are presented as No. (%).

Overall population (upper panel) and patients without coexisting CAD (lower panel).

Cox proportional hazard model for mortality: age, sex, reduced LVEF, CAD, complete revascularization (CAD and complete revascularization were excluded from the analysis in patients without CAD).

Kaplan-Meier curves at 1 year of follow-up for patients with and without angina. A: all-cause mortality in the overall population; B: cardiovascular mortality in the overall population; C: all-cause mortality in patients without CAD; D: cardiovascular mortality in patients without CAD. CAD, coronary artery disease.

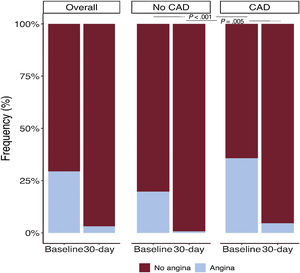

Among the 497 patients with angina at baseline, comprehensive follow-up data including a questionnaire on symptoms were available in 433 patients (87%). A total of 31 patients (7%) showed persistent angina at the 30-day follow-up and 90% of them (28 patients) had previously known significant CAD (significant stenosis on angiographic assessment pre-TAVR or status after coronary revascularization). In patients without CAD, persistent angina was virtually nonexistent (< 1%) at 30 days post-TAVR (figure 4). The baseline and procedural characteristics of patients with and without persistent angina 30 days post-TAVR are shown in table 3. Patients with persistent angina had a higher body mass index (30.6±5.0 vs 27.6±5.5; P=.004), a higher rate of diabetes mellitus (52% vs 35%; P=.065), a higher prevalence of CAD (90% vs 73%; P=.031), and a higher proportion of previous CABG (58% vs 34%; P=.008). There were no differences between groups in baseline echocardiographic parameters or procedural characteristics. Detailed information on the pre-TAVR coronary angiography findings and PCI in patients with and without persistent angina at 30 days post-TAVR is shown in . A total of 15 patients with persistent angina (48%) underwent repeat coronary angiography after TAVR and 7 patients (23%) underwent PCI (median interval between TAVR and PCI, 208 days [IQR, 169-319]). The predominant indication for post-TAVR PCI was angina in 6 patients (86%) and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in 1 patient.

Baseline and procedural characteristics, comparing patients with and without persistent angina at 30 days

| Total | No angina | Angina | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=433 | n=402 | n=31 | ||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 79.6±7.9 | 79.8±7.8 | 77.1±7.7 | .067 |

| Female sex | 171 (39) | 163 (41) | 8 (26) | .11 |

| Hypertension | 388 (90) | 359 (89) | 29 (94) | .46 |

| Diabetes | 157 (36) | 141 (35) | 16 (52) | .065 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.9 (5.5) | 27.6 (5.5) | 30.6 (5.0) | .004 |

| NYHA functional class> 2 | 294 (68) | 275 (68) | 19 (61) | .41 |

| Coronary artery disease | 320 (74) | 292 (73) | 28 (90) | .031 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 23 (21) | 84 (21) | 9 (28) | .318 |

| Previous PCI | 205 (47) | 187 (47) | 18 (58) | .21 |

| Previous CABG | 156 (36) | 138 (34) | 18 (58) | .008 |

| Complete revascularization | 290 (72) | 272 (73) | 18 (60) | .14 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 102 (24) | 94 (24) | 8 (26) | .77 |

| Chronic kidney diseasea | 193 (45) | 179 (45) | 14 (45) | .96 |

| Anemiab | 278 (64) | 259 (64) | 19 (61) | .73 |

| Cerebrovascular diseasec | 54 (12) | 48 (12) | 6 (19) | .23 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 120 (28) | 108 (27) | 12 (39) | .16 |

| EuroSCORE II | 4.5 [2.3-7.3] | 4.3 [2.3-7.3] | 5.1 [2.3-9.4] | .72 |

| LVEF | 54.4 (11.6) | 54.4 (11.8) | 54.3 (9.8) | .98 |

| LVEF ≤ 40 | 45 (10) | 42 (11) | 3 (10) | .89 |

| LVEF ≤ 40 (ischemic) | 36 (8) | 33 (8) | 3 (10) | .775 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | .71 |

| Aortic peak gradient, mmHg | 71.4 (24.9) | 71.6 (25.3) | 68.1 (18.7) | .44 |

| Aortic mean gradient, mmHg | 42.9 (15.9) | 43.1 (16.2) | 40.3 (11.5) | .35 |

| Mitral regurgitation> mild | 121 (28) | 114 (28) | 7 (23) | .49 |

| Procedural details | ||||

| Valve_type | ||||

| Balloon-expandable | 337 (78) | 311 (77) | 26 (84) | .40 |

| Self-expandable | 96 (22) | 91 (23) | 5 (16) | |

| Valve size, mm | 26.0 [23.0-29.0] | 26.0 [23.0-29.0] | 26.0 [23.0-29.0] | .62 |

| Valve-in-valve procedure | 37 (9) | 34 (8) | 3 (10) | .82 |

| Approach | ||||

| Transfemoral | 266 (61) | 246 (61) | 20 (65) | .71 |

| Non-transfemoral | 167 (39) | 156 (39) | 11 (35) | |

| Predilatation | 156 (38) | 149 (39) | 7 (23) | .073 |

| Postdilatation | 67 (16) | 64 (17) | 3 (10) | .30 |

| Postprocedural echo parameters | ||||

| LVEF | 55.30 (11.04) | 55.32 (11.19) | 55.00 (8.91) | .88 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 1.63 (0.48) | 1.63 (0.47) | 1.69 (0.61) | .55 |

| Patient-prosthesis mismatch | .77 | |||

| Moderate (iEOA ≤ 0.85 cm2/m2) | 99 (23) | 93 (23) | 6 (19) | |

| Severe (iEOA ≤ 0.65 cm2/m2) | 55 (13) | 50 (12) | 5 (16) | |

| Peak transaortic gradient, mmHg | 21.02 (9.78) | 21.02 (10.02) | 21.07 (6.13) | .98 |

| Mean transaortic gradient, mmHg | 11.30 (5.97) | 11.31 (6.15) | 11.18 (2.86) | .90 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; iEOA, indexed effective orifice area; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Values are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

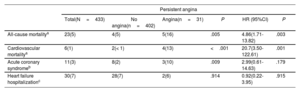

In contrast to angina at baseline, persistent angina at 30 days post-TAVR was associated with increased all-cause mortality (HR, 4.86; 95%CI, 1.71-13.8; P=.003) and cardiovascular mortality (HR, 20.7; 95%CI, 3.50-122.6; P=.001) at 1-year of follow-up (table 4). Kaplan-Meier curves at 1-year of follow-up, illustrating all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality post-TAVR according to the presence of persistent angina 30 days after TAVR, are shown in figure 5.

Comparison of event occurrence and risk for events at 1 year in patients with and without persistent angina 30 days after TAVR

| Persistent angina | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total(N=433) | No angina(n=402) | Angina(n=31) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| All-cause mortalitya | 23(5) | 4(5) | 5(16) | .005 | 4.86(1.71-13.82) | .003 |

| Cardiovascular mortalitya | 6(1) | 2(< 1) | 4(13) | <.001 | 20.7(3.50-122.61) | .001 |

| Acute coronary syndromeb | 11(3) | 8(2) | 3(10) | .009 | 2.99(0.61-14.63) | .179 |

| Heart failure hospitalizationc | 30(7) | 28(7) | 2(6) | .914 | 0.92(0.22-3.95) | .915 |

95%CI, confidence interval; HR, Hazard ratio.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed as No. (%).

Central illustration. Baseline/procedural characteristics and clinical outcomes comparing patients with and without angina undergoing TAVR for severe aortic stenosis. Kaplan-Meier curves at 1-year follow-up for patients with and without angina at baseline (left lower panel) and persistent angina at 30 days post-TAVR (right lower panel).

AVA, aortic valve area; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PG, pressure gradient; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

*Statistically nonsignificant.

The main results of this study are as follows: a) 29% of patients with severe AS undergoing TAVR had angina at baseline (20% among those patients with no significant CAD); b) TAVR recipients with angina at baseline were more commonly men, exhibited a worse NYHA functional class, a higher rate of CAD, a lower rate of complete revascularization, and a higher rate of nontransfemoral access routes; c) angina at baseline had no negative impact on clinical outcomes; d) persistent angina at 30 days post-TAVR was infrequent (7% of all patients with angina at baseline) and was practically nonexistent in patients without pre-existing CAD; however, its presence was associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 1-year of follow-up.

Significance of anginaSeveral prior studies on surgical patients showed that significant CAD was found in about half of patients with angina and underlying severe AS.12,15 In our TAVR population, CAD was found in 74% of patients with angina. In patients without angina, CAD was less common but was still reported in more than half of the patients (56%). In most studies, including our current publication, not just significant coronary stenosis but also previous CABG and previous PCI were accepted as definitions for CAD. Thus, the prevalence of significant CAD that may warrant revascularization pre-TAVR might be significantly lower than the reported numbers.16 This is supported by a recently published study by Case et al.17 showing significant CAD in 39% of TAVR candidates and need for preprocedural PCI in just 8.5% of patients. In our study population, PCI was performed in 22% of patients during the TAVR work-up.

The lower prevalence of CAD in the surgical (vs TAVR) series can be explained by the fact that TAVR patients are relatively older and exhibit a higher comorbidity burden. The question of whether angina is a reliable symptom to diagnose (or to exclude) CAD in patients with AS is controversial.18,19 The most consolidated thesis is that the presence or absence of angina in AS is of little help to predict or exclude a coexisting CAD and the current guidelines and standards still recommend coronary angiography in preparation for aortic valve replacement in all patients regardless of their angina symptoms.20,21 The relatively higher rate of patients with silent CAD (66%) in our TAVR population would support the current understanding, that the prediction or exclusion of significant CAD solely based on patients’ symptoms is unreliable.

Interestingly, study patients included a fairly high proportion of both patients with silent CAD and those with angina without significant CAD (about a fifth of all patients with angina at baseline). This group is particularly interesting to better understand angina symptoms secondary to AS, avoiding overlap with symptoms related to CAD. The current understanding of angina in patients without significant coronary artery stenosis is based on the following pathophysiological observations: myocardial oxygen consumption depends on heart rate, contractility and wall tension, which appears to be directly proportional to ventricular pressure.22 In AS, ventricular pressure and ventricular wall stress are elevated, causing increased oxygen demand. On the oxygen supply side, it is known that coronary blood flow in AS cannot be sufficiently increased due to the lower mean aortic pressure and diastolic perfusion time.22,23 Thus, angina in patients without significant CAD could be explained by the imbalance in oxygen supply and demand caused by the AS.24–27 In our study, angina in patients without CAD was not seen to be a sign of a more advanced valve disease, but these patients exhibited worse NYHA functional class and a lower rate of atrial fibrillation.

In the overall study population, patients with and without angina at baseline were similar in clinical baseline characteristics, except for a worse NYHA functional class, a higher incidence of CAD (including a higher rate of previous revascularization), a lower rate of complete revascularization, and a higher rate of nontransfemoral access routes in the angina group. The differences in complete revascularization between groups is striking. As patients with angina had more chronic total occlusions (nonsignificant trend) and more graft disease, the lower rate of complete revascularization might be explained by a more complex coronary anatomy and consequently a higher rate of revascularization failure. The higher rate of nontransfemoral access routes in the angina group can be explained by the higher prevalence of peripheral artery disease, as nontransfemoral arterial access routes are currently established as a safe alternative if the transfemoral approach is not feasible.28 The generally high rate of nontransfemoral access routes in our population (especially transcarotid access) is not only due to the series being historical, but also reflects the high penetration of alternative access routes in our center. In addition, a conspicuous finding was the large number of patients with prior revascularization in our population. This might be explained by the relatively advanced age of the overall population and a generally proactive practice in the treatment of significant CAD in our center.

In the past, patients with significant CAD and angina tended to have lower aortic valve gradients and larger valve areas.18,26 In our study, we also found a similar tendency to larger aortic valve area and lower valve gradients in the group of patients with angina. It can be speculated that myocardial ischemia leads to a drop in the mean aortic valve gradient and consequently to an increase in angina symptoms as a result of the reduced coronary flow. In addition, coexisting CAD may simply unmask the AS at lower gradients rather than causing the lower gradients.

Prognostic value of anginaIn the surgical population, CAD has been accepted as a negative prognostic factor,29,30 which has been the rationale for treating patients with severe AS and coexisting CAD in a combined procedure (surgical aortic valve replacement and CAGB). In the TAVR population, the impact of coexisting CAD on outcomes and the role of pre-TAVR revascularization is controversial. A meta-analysis by Sankaramangalam et al.31 analyzing 15 studies related to TAVR showed no impact of coexisting CAD on 30-day mortality but increased all-cause mortality at 1 year post-TAVR. Another meta-analysis showed no impact of concomitant CAD on outcomes at 1 year of follow-up after TAVR.32 In most centers, routine coronary angiography pre-TAVR is common practice, although data on the prognostic implication of CAD in TAVR candidates are ambiguous. Recently, the strategy of routine invasive coronary angiography pre-TAVR was questioned by a meta-analysis showing a lack of survival benefit at 30 days and 1 year and no improvement in cardiovascular outcomes among patients undergoing PCI for coexisting CAD pre-TAVR.33 In the ACTIVATION trial, the first randomized trial comparing PCI with medical treatment in patients with significant CAD undergoing TAVR, patients undergoing pre-TAVR revascularization did not show better outcomes.34 However, this trial was prematurely stopped, precluding definite conclusions. Considering that the benefit of PCI in TAVR candidates is uncertain, guideline-recommended optimal medical therapy for stable and asymptomatic CAD seems to be a suitable treatment option in TAVR candidates.35

To the best of our knowledge, the prognostic role of baseline angina had not been previously analyzed, either in the surgical or in the TAVR population. Therefore, our study is the first to demonstrate that angina at baseline had no impact on clinical outcomes at 1 year after TAVR, either in the overall population or in the subgroup of patients without coexisting CAD. The latter group is of particular interest, as contamination by symptoms of a coexisting CAD can be excluded.

Persistent angina in aortic stenosisIn our TAVR population, persistent angina at 30 days after TAVR was rare and almost exclusively seen in patients with known CAD. In patients without coexisting CAD, angina resolved after replacement of the diseased valve in> 99% of cases. The rare case of persistent angina in patients without CAD cannot be explained by our data and the cause was likely microvascular dysfunction. Interestingly, the completeness of preprocedural revascularization did not significantly differ between patients with and without persistent angina. Nevertheless, in the group with persistent angina, less than 50% of patients with a coronary intervention as part of the pre-TAVR work-up were completely revascularized. Thus, the relatively high rate of incomplete revascularization together with the considerable percentage of patients with persistent angina in need of a PCI within 1 year after TAVR suggest that persistent angina is mainly the result of a residual, occult or rapidly progressing disease of the coronary arteries and emphasizes the potential importance of complete revascularization in patients with angina at baseline. The hypothesis that in some patients CAD rapidly progresses after TAVR can also be derived from another publication, showing that about 10% of patients developed an acute coronary syndrome after TAVR (median follow-up of 25 months), whereas there were no differences in the completeness of revascularization pre-TAVR between patients with and without later acute coronary syndrome.36 Interestingly, Stefanini et al.37 recently reported an incidence of just 0.9% for unplanned PCI after TAVR with most PCIs in the first 2 years post-TAVR being due to an acute coronary syndrome. In accordance with the above-mentioned hypothesis, the most common angiographic finding was de novo lesions secondary to CAD progression. Interestingly, persistent angina post-TAVR not only led to repeat coronary angiography and PCI but also predicted higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 1 year after TAVR. This finding should be validated in larger study groups. Nevertheless, systematic evaluation of angina symptoms at follow-up and closer follow-up of those patients with persistent angina after TAVR seems to be advisable.

Study limitationsOur study reports the results from a single tertiary center with extensive experience in the treatment of valvular heart diseases. Thus, a center-specific bias cannot be ruled out. In addition, this was a retrospective analysis of prospectively gathered data. Alternative access routes such as the transcarotid approach for TAVR are commonly used in our center. The high percentage of nontransfemoral access routes may have had an impact on our results and should be considered as a possible limitation. Frailty and other relevant geriatric conditions were not included in our analysis. Equally, our analysis did not include medical treatment after TAVR. In particular, antianginal treatment is expected to contribute to symptoms relief and could have a relevant influence on persistent angina post-TAVR. Finally, in our center, the decision to perform revascularization pre-TAVR was the result of a Heart Team discussion and did not follow a prespecified selection.

CONCLUSIONSAngina occurred in 29% of TAVR candidates and was not found to be a sign of more advanced valvular disease or to have an impact on clinical outcomes following TAVR. Nevertheless, persistent angina after TAVR was associated with worse outcomes and should therefore be seen as a warning sign.

- -

Along with dyspnea and syncope, angina is known to be one of the cardinal symptoms in patients with severe AS.

- -

Angina is understood as a mismatch between myocardial oxygen demand and oxygen supply, either due to the AS itself or due to significant coexisting CAD.

- -

Angina at baseline was not found to be a sign of a more advanced valvular disease and had no impact on clinical outcomes following TAVR.

- -

Persistent angina after TAVR was associated with worse outcomes.

- -

Systematic evaluation of angina symptoms at follow-up should be considered, as well as closer a follow-up strategy in patients with persistent angina after TAVR.

L.S. Keller is supported by a grant from the KK Stiftung für Kardiologie und Kreislauf (Switzerland). J. Nuche is supported by a grant from the Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero (Madrid, Spain).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSL.S. Keller, J. Nuche, and J. Rodés-Cabau conceived and designed the study. L.S. Keller acquired the data. L.S. Keller and J. Nuche participated in data interpretation. L.S. Keller wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J. Nuche performed the statistical analysis, with input from J. Rodés-Cabau. All authors were involved in data interpretation, and in drafting and critically revising the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and ensured the accuracy and integrity of the work. All authors had access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. J. Rodés-Cabau is responsible for the overall content of the study as guarantor.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. Rodés-Cabau has received institutional research grants and speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific, and is consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

J. Rodés-Cabau holds the Research Chair Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions (Laval University, Quebec City, Canada).

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2023.04.004