Infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious infection, with a very high mortality rate; prevention is essential. Before the publication of the North American clinical practice guidelines (CPG) in 20071 and the European guidelines in 2009,2 IE prophylaxis was recommended for patients with high or moderate risk heart disease. In those CPGs, the indications were limited to patients with high risk of IE (previous IE, valve replacements, cyanotic congenital heart disease, or congenital heart disease repairs with prosthetic material) and only in certain dental procedures or manipulations.1,2 The 2008 British NICE guidelines recommended no IE prophylaxis in any situation.3 In the most recent European CPG from 2015, recommendations were unchanged from 2009.4 These differences could lead to uncertainty about the approach to patients with possible risk of IE, as was already suggested by a previous study carried out in Spain.5 Out aim was to describe the current practice of dentists in view of these recommendations and analyze whether the approaches were uniform in 2 Spanish provinces.

One-hundred dentists from Córdoba and 100 from Seville were invited to complete a questionnaire on IE prophylaxis, via the Official College of Dentists of Córdoba and the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Seville. The questionnaire was completed in full by 142 dentists; 62 in Seville and 80 in Córdoba (71% of all those invited; 62% in Seville and 80% in Córdoba). The chi-square test was used for comparisons between groups. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. There were no differences between the 2 provinces regarding the dentists’ age (44 ± 9 years in Seville vs 45 ± 10 years in Córdoba), years of practice (16 ± 5 vs 17 ± 5 in Córdoba) or sex (61.3% female in Seville and 51.2% in Córdoba, difference not statistically significant). Almost all (95.2%) of the respondents in Seville and 98.8% of those in Córdoba used prophylaxis in their everyday practice. Table 1A shows the dental procedures for which IE prophylaxis is indicated for at-risk patients. In most situations with a clear indication (surgery, implants, extractions, endodontics) or without indication (X-rays, anesthesia, removal of sutures, taking impressions for a prosthesis, fitting a removable prosthesis and orthodontic brackets), there was high compliance with the recommendations, except for endodontics and dental cleanings, in which antibiotic use was lower than recommended, and local anesthetic, in which use was higher than recommended (Table 1A).

Prescription of Infective Endocarditis Prophylaxis by Dentists in At-risk Patients According to Indication, Lack of Indication, Dental Procedure and Manipulations, and Type of Cardiac Disease

| A. Dental procedures and manipulations | Seville | Córdoba | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicated in CPGs | |||

| Oral/gingival surgery | 96.8% | 98.7% | .410 |

| Dental implants | 96.8% | 100% | .104 |

| Dental cleaning | 69.4% | 70.9% | .770 |

| Endodontics | 66.1% | 59.5% | .401 |

| Tooth extractions | 96.8% | 100% | .104 |

| Not indicated in CPGs | |||

| Taking impressions for fixed or implant prostheses | 14.5% | 8.9% | .269 |

| Taking impressions for removable prostheses | 6.5% | 3.8% | .450 |

| Fitting of removable prostheses | 8.1% | 1.3% | .054 |

| Fitting of orthodontic brackets | 3.2% | 3.8% | .877 |

| Fillings | 8.1% | 10.1% | .709 |

| Local anesthetic | 14.5% | 22.8% | .104 |

| Intraoral X-rays | 3.2% | 1.3% | .410 |

| B. Heart disease | Seville | Córdoba | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently indicated in CPGs | |||

| Valve replacement | 96.8% | 94.9% | .613 |

| Previous infective endocarditis | 96.8% | 100% | .104 |

| Cyanotic congenital heart disease or congenital heart disease repaired with prosthetic material | 90.3% | 86.1% | .185 |

| Previously but no longer indicated in CPGs | |||

| Significant aortic valve disease | 87.1% | 84.4% | .598 |

| Significant mitral valve disease | 88.7% | 84.4% | .416 |

| Pacemaker or ICD | 38.7% | 40.5% | .806 |

| Congenital heart disease with complete correction | 82.3% | 72.2% | .185 |

| Never indicated | |||

| Coronary stent | 56.5% | 67.1% | .160 |

| Aortocoronary bypass | 67.7% | 69.6% | .736 |

| Mild mitral prolapse | 48.4% | 58.2% | .318 |

| Closed ASD, VSD, or ductus with no residual defect | 66.1% | 67.1% | .823 |

| Atrial fibrillation without structural heart disease | 16.1% | 36.7% | .055 |

ASD, atrial septal defect; CPG, European or North American clinical practice guidelines; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Table 1B shows the heart conditions for which IE prophylaxis should and should not be used in dental interventions that carry risk. Of note is that in the 3 indications currently established by the North American and European CPGs (valve replacement, previous IE, cyanotic congenital heart disease or congenital heart disease repaired with prosthetic material), a very high proportion of dentists from both provinces used prophylaxis (Table 1B). In the case of prior indications that are no longer recommended, such as significant mitral or aortic valve disease, prophylaxis continues to be used by a very high proportion, as can be seen in Table 1B. However, even in situations without risk or with very low risk of IE (aortocoronary bypass, stents, isolated atrial fibrillation, mild mitral prolapse, closed interatrial or interventricular defects or ductus with no remaining defects) for which IE prophylaxis has never been recommended, it was prescribed by 50% to 70% of the dentists (Table 1B), with no differences between the 2 provinces studied.

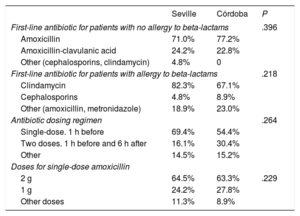

Table 2 shows the antibiotic regimens used for IE prophylaxis. A total of 35% of the dentists in Seville and 36.7% of those in Córdoba used different antibiotics to those recommended (amoxycillin 2g as a single dose 1h before procedure). When asked about which micro-organisms they hoped to eradicate with IE prophylaxis, only 9.7% of the Seville dentists and 18.0% of the Córdoba dentists responded Streptococcus viridans only, while 92.3% and 88%, respectively, thought that they were eradicating other micro-organisms, such as enterococcus, staphylococcus, and Gram-negative bacilli.

Prophylactic Antibiotic Regimens Used in Patients With and Without Beta-lactam Allergy

| Seville | Córdoba | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line antibiotic for patients with no allergy to beta-lactams | .396 | ||

| Amoxicillin | 71.0% | 77.2% | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 24.2% | 22.8% | |

| Other (cephalosporins, clindamycin) | 4.8% | 0 | |

| First-line antibiotic for patients with allergy to beta-lactams | .218 | ||

| Clindamycin | 82.3% | 67.1% | |

| Cephalosporins | 4.8% | 8.9% | |

| Other (amoxicillin, metronidazole) | 18.9% | 23.0% | |

| Antibiotic dosing regimen | .264 | ||

| Single-dose. 1 h before | 69.4% | 54.4% | |

| Two doses. 1 h before and 6 h after | 16.1% | 30.4% | |

| Other | 14.5% | 15.2% | |

| Doses for single-dose amoxicillin | |||

| 2 g | 64.5% | 63.3% | .229 |

| 1 g | 24.2% | 27.8% | |

| Other doses | 11.3% | 8.9% | |

The main conclusion of our study is that there is a notable knowledge gap and noncompliance with the current recommendations on IE prophylaxis among dentists in our setting, with overuse in patients in whom it is not currently recommended and, above all, in patients without risk of IE after dental procedures (those with coronary stents, aortocoronary bypass, mild mitral prolapse or even atrial fibrillation without structural disease). This could be an example of what has been described as the “no lose” philosopy.6 With the limitations of this study, which are those inherent to a voluntarily-completed questionnaire, it appears that there is a notable knowledge gap among dentists in our setting about important aspects of the recommended IE prophylaxis regimens. This translates to an excessive use of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients not at risk of IE. This knowledge gap was similar and uniform in the 2 provinces studied. It therefore seems necessary to develop educational strategies on this disease for all the professional groups involved. To achieve this, the coordination and collaboration of all the related scientific societies will be essential.