Caseous calcification of mitral annulus, also known as caseoma, is a rare echocardiographic finding. Because it often presents asymptomatically, the diagnosis is usually incidental. The condition arises due to caseous degeneration in the internal material of the mitral annulus calcification. On echocardiography, the calcification is a round mass with a central echolucent area, typically located at the base of the posterior leaflet, and can be mistaken for cardiac tumors or abscesses. We describe 3 patients with the condition, one of whom required surgical removal of the mass to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Keywords

Caseous calcification of the mitral annulus (CCMA) is a rare variant of mitral annulus calcification, a chronic degenerative process that occurs at advanced ages, particularly in women, hypertensive individuals, and patients with chronic renal failure or calcium metabolism abnormalities. The condition usually arises in the basal area of the posterior mitral valve and can extend over the entire annulus.1, 2

Caseous calcification of the mitral annulus represents a rare course of the process, in which caseous degeneration of the internal material occurs. It is composed of a calcified rounded covering and, in its interior, a “toothpaste-like” mixture of calcium, fatty acids, and cholesterol.1, 2

MethodsWe present 3 patients with the condition, one of whom required surgical resection of the mass to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Results Patient 1A 66-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease as well as percutaneous revascularization of the anterior descending artery was admitted for new angina symptoms upon minimal exertion. Coronary angiography confirmed severe, diffuse disease in the anterior descending artery and first diagonal branch that precluded percutaneous revascularization. The patient was scheduled for surgical revascularization.

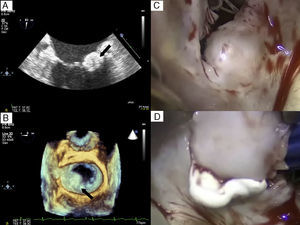

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed a rounded mass of 15×16 mm in the posterior mitral annulus that extended to the most basal area, the P1-P2 scallops, without causing valve stenosis and with only minimal mitral regurgitation (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1. A: Transesophageal echocardiography in the bicommissural plane of the mitral valve showing a rounded, calcified mass with interior content of lower echogenicity. B: Image obtained with 3-dimensional echocardiography clearly showing how the mass affects P1-P2 and protrudes into the left atrium. C: Intraoperative image of the mass. D: Pasty content removed after the incision.

Because a cardiac tumor was initially suspected and the patient was scheduled for revascularization surgery, a decision was made to remove the mass during the operation. During the procedure, an incision was made and a whitish pasty content was removed (Figure 2C and D).

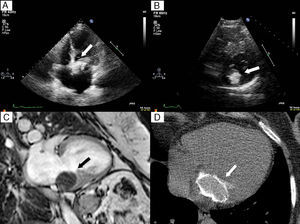

Figure 2. A: Transthoracic echocardiogram with 4-chamber apical view. B: Short-axis parasternal view also showing a large calcified mass. C: 2-chamber view in gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging, in which the mass is hypointense with respect to the adjacent myocardium. D: Axial computed tomography scan showing the calcified envelope.

Patient 2A 72-year-old woman with a prior history of hypertension, asthma, and deep vein thrombosis came to the hospital for fatigue and nonspecific dizziness in the previous 3 weeks.

At admission, paroxysmal complete atrioventricular block was diagnosed and a dual-chamber pacemaker was implanted during hospitalization.

The TTE showed a large calcified mass of 30×30 mm in the left atrium (Figure 2A and B) that caused moderate valve stenosis with a mean pressure gradient of 6 mmHg. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed that the lesion was located at the base of the posterior leaflet, extending medially toward the most apical portion of the interatrial septum and to the interventricular membranous septum. The lesion was hypointense with respect to the myocardium in the T1- and T2-weighted sequences and gradient echocardiography (Figure 2C), and only presented late-phase enhancement in the surrounding capsule. These findings, as well as the presence of a calcified envelope in the cardiac computed tomography scan (Figure 2D), confirmed the suspicion of caseous calcification of the mitral annulus.

The symptoms resolved once the pacemaker was implanted and therefore a wait-and-see approach was taken.

Patient 3A 71-year-old woman with a history of hypercholesterolemia and complete hysterectomy for an ovarian tumor had experienced 2 episodes of syncope in the last few months, with no obvious accompanying sweating or nausea. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a new bifascicular block. No episodes of advanced atrioventricular blocks or significant pauses were observed in the 24-h Holter-ECG monitoring.

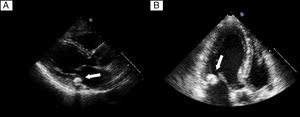

The study was completed with TTE, which revealed a rounded, calcified mass of 15×14 mm at the base of the posterior mitral leaflet, extending medially toward the interventricular septum but without causing significant valve stenosis or regurgitation (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3. A: Transthoracic echocardiogram at long-axis parasternal view. B: 3-chamber apical view showing a typical image of caseous calcification of the mitral annulus with virtually no posterior acoustic shadow.

DiscussionEchocardiographic series report a low prevalence of CCMA, between 0.06% and 0.07%, and up to 0.6% of patients with calcification of the mitral annulus (CMA).1 The prevalence in autopsies is much higher and is 2.7%3 of the population studied.

The condition is probably underdiagnosed because of the asymptomatic course in most patients, although there have been several reports of CCMA associated with mitral valvular dysfunction, both stenosis4 and regurgitation, due to the structural deformation it causes.

In our series, we observed a high frequency of conduction abnormalities: one of our patients presented advanced atrioventricular block, and another, the third patient, had a bifascicular block with repetitive syncopes. Although this association has been previously described in CMA, there is no evidence regarding a specific association with CCMA, probably due to a low incidence.

The association between CMA and other diseases such as atrial fibrillation, aortosclerosis, and coronary artery disease has been widely studied. In the case of conduction system diseases, the association is 26% to 70% according to the series.5, 6

Because the mitral annulus is close to the region of the atrioventricular node and the His-Purkinje system, any extension of calcified deposits would affect how these electrical structures function, leading to intraventricular conduction delays. This occurs particularly in cases in which CMA extends to the anterior annulus and more medial segments of the posterior annulus and mainly in the form of complete left bundle branch blocks and bifascicular blocks.7

Nevertheless, the frequency of this association must be considered with caution because the occurrence of both phenomena is related to age and the degenerative changes may take place independently.

The initial diagnosis is made on echocardiography. On occasion, the chest X-ray may reveal a calcified mass in the cardiac silhouette. Transthoracic echocardiography will show a spherical mass, with calcified borders and an echolucent area in its interior, that is located near the annular region of the posterior mitral leaflet and does not usually produce an acoustic shadow.1, 2

The differential diagnosis should include cardiac abscesses and tumors.8 In addition to the clinical course, the characteristic calcified, well-defined borders and their typically posterior site help differentiate them from abscesses, usually located in the mitroaortic fibrous continuity. In the case of tumors, the absence of interior echolucency is observed.

Additional imaging studies may aid the final diagnosis. Transesophageal echocardiography1 will provide more information on the site and composition of the internal material although the diagnosis will be greatly aided by computed tomography,4 given its capacity to detect the calcified envelope, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.9 In cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, the characteristics of the various sequences will help distinguish the condition from other tumors, and the signal is normally hypointense with respect to myocardium in the gradient echocardiography and T1- and T2-weighted sequences, with little to no contrast uptake at the periphery of the mass.

Due to the asymptomatic course, only monitoring of the patient's progress is recommended in most cases. Surgery should be reserved for patients with significant valvular dysfunction or an uncertain diagnosis.2, 4, 9 Self-limiting cases have been reported,1, 10 which suggests a dynamic component of the lesion that can regress to CMA during its course.

In conclusion, CCMA is a rare variant of CMA, but should be considered in the differential diagnosis with other cardiac masses to prevent unnecessary surgery.

This article indicates that, like CMA, CCMA may be associated with infra-Hisian conduction abnormalities.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Received 3 November 2010

Accepted 22 December 2010

Corresponding author: Canciller Ayala 1, 4.o izquierda-izquierda, 48008 Bilbao, Vizcaya, Spain. noragarcib@hotmail.com