The atypical characteristics of acute coronary syndrome in women lead to differences in management and treatment. We investigated these differences in the urgent management of non-ST-segment acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Data on 39 variables were collected from 539 patients with NSTEMI treated at 97 Spanish emergency departments. After adjustment for 10 baseline differences, the only significant differences were that time-to-arrival at the emergency department was longer for women (odds ratio [OR]=0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28-0.95) and that they received more clopidogrel (OR=1.65; 95% CI, 1.06-2.56). The trend to fewer admissions to coronary or intensive care units (42.9% vs 55.6%) and fewer catheterization procedures (29.7% vs 40.7%) disappeared after adjustment.

We conclude that there are virtually no differences in treatment in women with N-STEMI in prehospital and emergency care.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONThe atypical characteristics of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in women leads to differences in management; specifically, lower rates of coronary catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and revascularization.1 As a large proportion of the diagnostic and therapeutic processes are conducted in hospital emergency departments (HED), some of these differences could have their origin at this first care level. The present study investigated this hypothesis using data provided by the MUSICA (Manejo en Urgencias del Síndrome Coronario Agudo - Emergency Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes) registry.

METHODS MUSICA RegistryMUSICA is an epidemiological, observational, retrospective, multicenter registry of ACS patients collected from 97 Spanish HED with different care levels, selected by convenience sampling between November 2007 and February 2008. It included patients over 18 years of age with chest pain and confirmed ACS based on the MASCARA study definitions,2 and who either attended the HED on their own initiative or who were transferred there by the prehospital medical emergency system. Each center consecutively included 15 patients: the first 10 diagnosed with non-ST-segment elevation ACS and the first 5 diagnosed with ST-segment elevation ACS (STEACS). The registry was approved by the clinical research ethics committee.

A questionnaire was completed for each patient providing details of their baseline epidemiological characteristics and the ACS episode using prehospital, emergency, and discharge reports. When necessary, the variable was dichotomized based on clinical criteria.

Study DesignThe present study was a subanalysis of the MUSICA registry and included all the patients with non-ST-segment acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). This group of patients was chosen as they had been diagnosed objectively, had a prolonged stay in the emergency department, and had undergone a well-defined set of diagnostic-therapeutic procedures initiated during prehospital care and completed in the HED.3 The outcome variables included: a) treatment administered during emergency care classified as class IA in the European Society of Cardiology 2007 guidelines (antiplatelet agents, any heparin, betablockers [BB])3; b) care times (pain onset-to-arrival in the emergency room <1 h; door-to-electrocardiogram (ECG) <10min; total stay in the emergency department <8h), and c) final destination (discharge, conventional admission or coronary intensive care units). Given that some procedures usually performed during hospitalization are performed if the patient is in the emergency room, the percentages of ECG, coronary catheterization, PCI, and surgical revascularization were recorded, regardless of where the patient was at the time of the procedure.

Statistical AnalysisQuantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as median [interquartile range] and compared using ANOVA or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test; qualitative variables are expressed as absolute values and percentages and compared using χ2 test or Fisher test. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated (men: value 1, reference category) adjusted using a logistic regression model for the variables with an unequal distribution between sexes. The differences were considered significant at a P value of <.05 or if the 95% CI excluded value 1.

RESULTSThe MUSICA registry included 583 patients with NSTEMI; of these, 132 (22.6%) arrived by emergency ambulance. In total, 90.7% of the clinical history data were available, with no differences between the sexes regarding loss of data. Women were older, had higher Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk scores, greater body weight, and a greater frequency of hypertension, diabetes, previous ischemic heart disease, and ACE inhibitor therapy, and a lower frequency of smoking, less chest pain, and a lower Killip class I at arrival in the emergency department (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Patients.

| Total (n=583) | Women (n=175) | Men (n=408) | P | |

| Epidemiological variables | ||||

| Age (y) | 69±12 | 76±11 | 67±13 | <.001 |

| Tertiary or referring hospital | 374 (64.2) | 111 (63.4) | 263 (64.5) | .89 |

| Patient attending on own initiative without prior medical consultation | 253 (43.6) | 70 (40) | 183 (44.9) | .32 |

| Transferred from a lower level hospital | 22 (3.8) | 9 (5.1) | 13 (3.2) | .37 |

| Transferred to emergency unit by emergency ambulance | 132 (22.6) | 40 (22.9) | 92 (22.5) | 1 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 401 (68.8) | 142 (81.1) | 259 (63.5) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 212 (36.4) | 88 (50.3) | 124 (30.4) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 233 (40) | 71 (40.6) | 162 (39.7) | .92 |

| Kidney failure | 43 (7.4) | 15 (8.6) | 28 (6.9) | .58 |

| Smoking | 155 (26.6) | 16 (9.1) | 139 (34.1) | <.001 |

| Drug dependency | 4 (0.7) | 3 (1.7) | 15 (3.7) | .32 |

| Family background of AMI in those <50 years old | 18 (3.1) | 3 (1.7) | 15 (3.7) | .32 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Documented previous ischemic heart disease | 252 (43.2) | 91 (52) | 161 (39.5) | <.01 |

| Heart failure | 49 (8.4) | 21 (12) | 28 (6.9) | .06 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 50 (8.6) | 17 (9.7) | 33 (8.1) | .63 |

| Transient or established stroke | 47 (8.1) | 16 (9.1) | 31 (7.6) | .64 |

| Intermittent claudication | 30 (5.1) | 4 (2.3) | 26 (6.4) | .07 |

| Treatment associated with ischemic heart disease | ||||

| ASA | 164 (28.1) | 52 (29.7) | 112 (27.5) | .65 |

| Clopidogrel | 78 (13.4) | 26 (14.9) | 52 (12.7) | .58 |

| Ticlopidine | 5 (0.9) | 0 | 5 (1.2) | .33 |

| Dicoumarol | 34 (5.8) | 14 (8) | 20 (4.9) | .2 |

| Heparin | 6 (1) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (1) | 1 |

| Nitrates | 66 (11.3) | 22 (12.6) | 44 (10.8) | .63 |

| Betablockers | 123 (21.1) | 39 (22.3) | 84 (20.6) | .73 |

| ACEI | 156 (26.8) | 57 (32.6) | 99 (24.3) | <.05 |

| Clinical manifestations of the ACS episode | ||||

| Chest pain on arrival at emergency room | 315 (55) | 78 (45.9) | 237 (58.8) | <.01 |

| 2 or more episodes in the last 24 h | 230 (40.1) | 72 (41.4) | 158 (39.5) | .74 |

| TIMI score | 3.5±1.4 | 3.8±1.3 | 3.4±1.4 | <.01 |

| Recurrent angina | 38 (6.5) | 8 (4.6) | 30 (7.4) | .29 |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 142±29 | 145±30 | 141±29 | .13 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 84±20 | 84±19 | 83±20 | .45 |

| Body mass index | 27.8±4.7 | 28.6±5.2 | 27.5±4.5 | <.05 |

| Killip class I | 101 (17.3) | 43 (24.6) | 58 (14.2) | <.01 |

| Abnormalities on first ECG | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 62 (11.1) | 25 (14.7) | 37 (9.4) | .09 |

| Branch blocks | 145 (24.9) | 49 (28) | 96 (23.5) | .3 |

| Abnormal ST segment | 374 (64.2) | 116 (66.3) | 258 (63.2) | .54 |

| Blood test | ||||

| Troponins (x times upper limit) | 12±3.9 | 11.7±3.8 | 12±4 | .54 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2±0.8 | 1.1±0.7 | 1.2±0.8 | .64 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; bpm, beats per minute; ECG, electrocardiogram; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

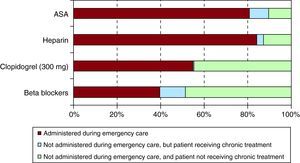

Regarding outcome variables (Table 2), the bivariate analysis did not show significant differences in treatment administered in the emergency department. In total, 80.8% received acetylsalicylic acid; 54.9%, a loading dose of clopidogrel; 84%, heparin; and 39.6%, BB (Figure 1). Neither were there differences in the 3 care times, but fewer women were admitted to coronary intensive care units and they underwent fewer catheterization procedures.

Table 2. Intervention Variables Analyzed in the Study and Their Behavior According to Sex.

| Total (n=583) | Women (n=175) | Men (n=408) | P | |

| Treatment in emergency unit | ||||

| Prehospital and hospital | ||||

| ASA treatment | 471 (80.8) | 142 (81.1) | 329 (80.6) | .98 |

| Clopidogrel loading dose 300 mg | 320 (54.9) | 102 (58.3) | 218 (53.4) | .2 |

| Heparin treatment | 490 (84) | 151 (86.3) | 339 (83.1) | .4 |

| Betablocker treatment | 231 (39.6) | 61 (34.9) | 170 (41.7) | .15 |

| Anti-GPIIb/IIIa treatment | 56 (9.7) | 12 (7) | 44 (10.9) | .19 |

| Prehospital emergencies (only patients transferred by emergency ambulance, n=132) | ||||

| ASA treatment | 58 (43.9) | 13 (32.5) | 45 (48.9) | .12 |

| Clopidogrel loading dose 300 mg | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 1 |

| Heparin treatment | 17 (12.9) | 3 (7.5) | 14 (15.2) | .35 |

| Betablocker treatment | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (2.2) | .87 |

| Hospital emergency department | ||||

| ASA treatment (n=455) * | 343 (74.5) | 111 (77.1) | 233 (74.6) | .65 |

| Clopidogrel loading dose 300mg (n=547) * | 284 (51.9) | 93 (56) | 191 (50.1) | .24 |

| Heparin treatment (n=520) * | 427 (82.1) | 133 (84.7) | 294 (81) | .37 |

| Betablocker treatment (n=563) * | 211 (37.5) | 56 (32.9) | 155 (39.4) | .17 |

| Anti-GPIIb/IIIa treatment (n=574) * | 56 (9.7) | 12 (7) | 44 (10.9) | .19 |

| Care times in emergency units (h) | ||||

| Pain onset-to-arrival at emergency unit time | 2.1 [4.9] | 2.1 [5.1] | 2.2 [4.3] | .67 |

| Door-to-ECG time | 10 [17] | 11 [22] | 10 [16] | .13 |

| Total time in emergency unit | 7 [10.2] | 7.5 [9.5] | 6.2 [9.3] | .16 |

| Patient destination | ||||

| Admitted to coronary intensive care unit | 302 (51.8) | 75 (42.9) | 227 (55.6) | <.01 |

| Hospital care | ||||

| Echocardiography | 269 (46.1) | 71 (40.6) | 198 (48.5) | .09 |

| Coronary catheterization | 218 (37.4) | 52 (29.7) | 166 (40.7) | <.05 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 105 (18) | 24 (13.7) | 81 (19.9) | .1 |

| Coronary revascularization surgery | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | 1 |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; anti-GPIIb/ IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/ IIIa inhibitors; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Data are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range].

* Number of patients not treated during prehospital emergency care and candidate for treatment during hospital emergency department care.

Figure 1. Proportion of patients who received the main treatments indicated for non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction during urgent medical care in prehospital or hospital settings. ASA, acetylsalicylic acid.

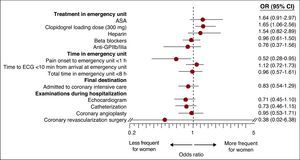

When these outcome variables were adjusted for the 10 unequally distributed independent variables, the only differences were that the time to arrival at the emergency department was longer for women and they more frequently received the loading dose of clopidogrel (Figure 2). However, although a trend was observed toward women undergoing fewer interventions during hospitalization, this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals by sex for the different intervention variables adjusted for baseline factors or the acute episode that were significantly different. ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CI, confidence interval; ECG, electrocardiogram; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSIONThis is the first Spanish multicenter study to investigate potential sex differences in the diagnosis and management of patients with NSTEMI in the HED. The results suggest that there is no difference in treatment between the sexes. There are few studies with which the results can be compared. The most noteworthy results are provided by the CRUSADE registry, which collected more than 35 000 care patterns of HED patients with ACS up to 2002.4 It concluded that women had a greater risk profile, but received less aggressive treatment than men from the time of arrival at the emergency room and during admission. Our study is consistent with this registry in that women presented a greater risk profile, but they did not receive less treatment in the HED.

In Spanish HEDs, and to date, the influence of sex has only been analyzed on the management of patients with general chest pain5 and those with STEACS,6 although no significant differences were found. Currently, apart from making an immediate diagnosis after the first ECG, the emergency physician in STEACS in hospitals with primary angioplasty available plays a minimal role. In contrast, they have a stronger role in the context of NSTEMI. These patients stay longer in the HED, since diagnosis is often delayed between 6-8 h until a positive marker of necrosis has been obtained; furthermore, the first therapeutic measures should be applied as soon as possible during this period, since the final prognosis depends on them. The present study shows that none of the measures considered as class IA in the current European cardiology guidelines3 reached 100% compliance, although the percentages were similar to those of the CRUSADE registry.4 It is difficult to know whether a ceiling has been reached or if by analyzing the possible causes this percentage can be improved. Among these causes, there is the difficulty in establishing an accurate initial diagnosis of NSTEMI in the HED. The introduction of new diagnostic imaging techniques7, 8 and highly sensitive cardiac biomarkers9 should lead to faster identification. Finally, it should be noted that neither were there differences in prehospital management. In this case, the possibility of establishing and improving initial treatment is even greater, although the diagnostic difficulties are greater than in HED.

Regarding limitations, it should be taken into account that this was a multicenter study using a sample in which geographic representation was prioritized over population representation. Second, as this was an observational retrospective study, the possibility of an inclusion bias cannot be completely excluded. Third, around 9% of the data were not available. Fourth, the size of the sample was relatively small and thus the statistical power for some of the comparisons was low and may not have been sufficient to detect differences between sexes. Fifth, some of the differences found may have been due to sexist attitudes among the patients or family members, although this possibility was not investigated. Finally, many variables play a role in the care process of ACS patients, some of which are confounders and may not have been taken into account. Despite this, we can conclude that the management of patients with NSTEMI in the HED is similar in both sexes. Management is not influenced by the different profiles of the patients or by the fact that the time from symptom onset to arrival at medical emergency services or the HED is longer for women. Nevertheless, this study has uncovered the need for improvements in certain areas, such as optimizing the management of NSTEMI patients in Spanish emergency services.

FUNDINGDr. Òscar Miró received a research grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III during 2009. The present study was supported by SANOFI-AVENTIS, but this company did not participate in the analysis of the results, the discussion, or drafts of the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

Received 19 February 2011

Accepted 25 February 2011

Corresponding author: Área de Urgencias, Hospital Clínic, Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain. msanchez@clinic.ub.es